Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

Governments should do everything possible to avoid recessions – yet they don’t

In May 2020, the IMF published a new Working Paper (No 20/73) – Hysteresis and Business Cycles – which provides some insights into what happens during an economic cycle. The IMF are somewhat late to the party as they usually are. We have known about the concept and relevance of hysteresis since the 1980s. In terms of the academic work, I was one of the earliest contributors to the hysteresis literature in the world. I published several articles on the topic in the 1980s that came out of my PhD research as I was searching for solutions to the dominant view in the profession that the Phillips curve constraint prevented full employment from being sustained (the inflation impacts!). The lesson from this literature in part – especially in current times – is that governments should do everything possible to avoid recessions. The hysteresis notion tells us clearly that the future is path dependent. The longer and deeper the recession, the more damaging the consequences and the longer it takes to recover while enduring these elevated levels of misery. Organisations like the IMF have never embraced that sort of reasoning, until now it seems. They certainly didn’t act in this way during the Greek disaster. But, better late than never.

I have written a lot about hysteresis – among other blog posts:

1. Redefining full employment … again! (May 5, 2009).

2. Long-term unemployment rising again (April 13, 2009).

You can also read some of my earlier refereed academic articles on the topic if you want more analytical depth:

1. The NAIRU, Structural Imbalance and the Macroeconomic Equilibrium Unemployment Rate – published in Australian Economic Papers, June 1987.

This paper, in fact, was written and submitted to the journal before the famous Blanchard and Summers paper was published in 1986. The editorial process for my paper was slow and so it came out after the BS paper, which was then held out as the pathbreaking paper in the field. Timing matters.

2. Australian Wage Inflation: Real Wage Resistance, Hysteresis and Incomes Policy: 1968(3)-1988(3) – written with Martin Watts and published in The Manchester School, June, 1990.

3. Testing for Unit Roots and Persistence in OECD Unemployment Rates – published in Applied Economics, December, 1993.

This paper received a hostile reception from some leading mainstream economists who realised what the findings meant but wanted to suppress the relevance.

The significant of hysteresis

The IMF Working Paper conjectures about the “shape and length of the recession, as well as the steepness of the recovery”.

You can read an Op-Ed summary of the paper here -> The persistence of a COVID-induced global recession (May 14, 2020).

You hear a lot about V-shaped cycles and other more exotic geometric shapes to describe the transition from the peak of the economic cycle to the trough and back again.

I even saw some reference to a ‘square root’ path the other day.

The Australian government definitely had a V-shape in their mind in early March as the reality of the necessity of a lockdown to quell the virus infection rate became obvious.

They initially talked about a ‘hibernation’ strategy – where they would put the economy to sleep while the worst of the pandemic passed and then turn the lights back on as if nothing happened.

The design of their limited stimulus – the wage subsidy and some increase in the unemployment benefit definitely was influenced by this vision.

Quick descent, quick recovery – V-shaped.

I discussed why that was not likely to be a good assumption in this blog post – The government should pay the workers 100 per cent, not rely on wage subsidies (March 31, 2020).

The V-shape imagery is a way conservatives console themselves after opposing any form of fiscal activism and then realising that their own prosperity might be actually at stake (political and/or economic) as recession looms and that they have to use government stimulus as a solution.

By claiming it will be all over soon, they can feel easy within their twisted ideological minds, that they can get back to fiscal austerity (that harms the disadvantaged on a permanent basis but leaves the top-end-of-town largely unscathed) and all will be well again with the world.

What history tells us is that recessions are rarely V-shaped. At best they appear to be a sort of elongated V with deep asymmetry – the descent is rapid and the recovery slow and drawn out.

The extent of the elongation is crucially dependent on how fast the government stimulus enters the spending system, how it is designed, and how long the support is maintained.

During the GFC, most governments initially opted for discretionary stimulus. But the neoliberals forced many governments to reverse the stimulus too soon and the results were for all to see.

For the Eurozone such a strategy demanded by their ridiculous fiscal rules has created a catastrophe.

For Britain after Cameron was elected in May 2010, the austerity prolonged recovery and has had lasting consequences.

In Australia, the then Labor government acted correctly to introduce a large and well-timed stimulus in late 2008 but by 2012 had reverted to their modern ‘neoliberal’ form and introduced one of the biggest fiscal shifts in history (towards austerity) which stopped economic growth and unemployment reduction in its tracks and meant that by the time the current pandemic hit, Australia was growing close to half its previous trend rate, unemployment remained well above the pre-GFC low, and there were around 13.5 per cent of available workers either unemployed or underemployed.

All of those examples among many are about hysteresis.

The IMF authors say that:

… deep recessions have typically led to economic scarring in the long term, what we call hysteresis …

The question that many officials failed to answer correctly in the early stages of the crisis was how much of the current productive infrastructure will disappear as a result of the prolonged shutdowns.

It is clear that this is a different crisis.

A lockdown is reversible overnight if the government dictates – and we have seen Levels of lockdown defined as the government eases the harshness slowly within the constraints of the infection rate.

It was that vision that led to the early V-shaped claims.

But anecdotal evidence (wandering around centres of major cities, for example) suggests that many established business have been destroyed by the closures and will not return.

We won’t know the full effects until some semblance of recovery is sustained.

The IMF authors note that what hysteresis tells us is that it is impossible to separate analysis of economic growth from economic cycles.

Mainstream economists have typically separated analysis of long-term growth from so-called ‘business cycle’ analysis.

The former was considered to be determined by such factors as population growth and rates of capital accumulation (which drove productivity growth through technological innovation), and, which defined a potential growth path for a nation.

Business cycle analysis then analysed deviations around the long-term trend growth path.

The extreme versions of this separation conjectured that so-called ‘technology shocks’ (like a new machine or the digital innovation) would permanently alter growth paths but aggregate demand policy interventions would at best be temporary.

In other words, the mainstream position was that demand interventions by government would be small in impact and temporary, giving way to the dominant impacts on economic trajectories (technology etc).

The mainstream economists also believed that the demand impacts would be symmetrical – a stimulus would have small, temporary impacts giving way to inflationary pressures, and, austerity would work symmetrically in the opposite way.

So in the 1980s and 1990s we started to hear about “short, sharp shocks” and “shock therapy” as a strategy recommended by mainstream economists to address inflationary pressures. These shocks required deep fiscal contractions, which they claimed would expunge the price pressures and have hardly any real effects (that is, not damage GDP growth for long and elevate unemployment).

This is what the NAIRU and Real Business Cycle and New Keynesian economics is all about.

One of the reasons we did not have a separate chapter on ‘growth’ in our MMT text book – Macroeconomics – despite criticism from some orthodox reviewers, was because we do not see growth and cycle as being separable in the way mainstream economists treat the topic.

The mainstream economists also started to run a line about as outlined in the IMF paper that there were “positive, cleansing, effects of recession” where “uncompetitive firms go out of business” and stronger businesses see that their “unused productive resources that can be deployed to research activities and this reassignment of resources could increase growth in the long term”

In my own work in the 1980s as a postgraduate student and early career academic, I emphasised that running an economy into recession was the worst thing a government could do.

The IMF paper quotes James Tobin (an American Keynesian economist) from 1980, which challenged the mainstream view on recessions:

With respect to human capital, as well as to physical capital, demand management has important long-run supply-side effects. A decade of slack labor markets, depriving generations of young workers of job experience, will damage the human capital stock far beyond the remedial capacity of supply-oriented measures.

That quote is really about hysteresis.

What is it?

The hysteresis notion tells us clearly that the future is path dependent. Where you are now is where you have been.

In brief, hysteresis is a term drawn from physics and is used in economics to describe where we are today as a reflection of where we have been. That is, the present is path-dependent.

An economy cannot escape its history. Mainstream economics largely ignores history or culture. The textbook models are ahistorical and assume that free market competitive principles apply universally across space and time.

To understand what happens during a recession it is useful to understand the cyclical labour market adjustments that occur.

The significance of hysteresis is that the unemployment rate associated with stable prices, at any point in time – which is sometimes called the equilibrium unemployment rate – should not be conceived of as a rigid non-inflationary constraint on expansionary macro policy. The equilibrium rate itself can be reduced by policies, which reduce the actual unemployment rate.

This is what my 1987 paper cited above is about.

The idea is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reversed. Structural imbalance refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to present themselves as an effective excess supply.

The non-wage labour market adjustment that accompany a low-pressure economy, which could lead to hysteresis, are well documented. Training opportunities are provided with entry-level jobs and so the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall. New entrants are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns) and redundant workers face skill obsolescence. Both groups need jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

In a recession, many firms disappear all together, particularly those who were using very dated capital equipment that was less productive and hence subject to higher unit costs than the best practice technology.

The skills associated with using that equipment become obsolete as it is scrapped. This phenomenon is referred to as skill atrophy. Skill atrophy relates not only to the specific skills needed to operate a piece of equipment or participate in a firm-specific process.

Long-term unemployment also erodes more general skills as the psychological damage of unemployment impacts on a worker’s confidence and bearing. A lot of information about the labour market is gleaned informally via social networks and there is strong evidence pointing to the fact that as the duration of unemployment becomes longer the breadth and quality of an unemployed worker’s social network falls.

Further, as training opportunities are typically provided with entry-level jobs it follows that the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall.

New entrants to the labour force – into the unemployment pool because of a lack of jobs – are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns).

As a result, both groups of workers – those made redundant and the new entrants – need to find jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

Therefore, workers enduring shorter spells of unemployment, other things equal, will tend to be more to the front of the queue. Firms form the view that those who are enduring long-term unemployed are likely to be less skilled than those who have just lost their jobs and with so many workers to choose from firms are reluctant to offer any training.

However, just as the downturn generate these skill losses, a growing economy will start to provide training opportunities as the unemployment queue diminishes. This is one of the reasons that economists believe it is important for the government to stimulate economic growth when a recession is looming to ensure that the skill transitions can occur more easily.

The long-run is thus never independent of the state of aggregate demand in the short-run. There is no invariant long-run state that is purely supply determined.

By stimulating output growth now, governments also help relieve longer-term constraints on growth – investment is encouraged and workers become more mobile.

The supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken.

Hysteresis means that where you are today is a function of where you were yesterday and the day before that.

However, the longer a recession (that is, the output gap) persists the broader the negative hysteretic forces become. At some point, the productive capacity of the economy starts to fall (supply-side) towards the sluggish demand-side of the economy and the output gap closes at much lower levels of economic activity.

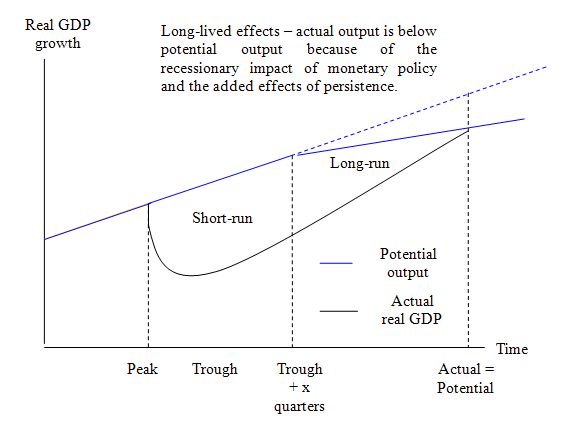

Another way of looking at the issue is captured by the following diagram.

In a recession, business investment starts to taper off because firms have ample productive capacity to meet the depressed expenditure levels. They also become pessimistic and wait until they are sure recovery is strong before investing in new productive capacity because of the uncertainty.

So initally as spending falls, real GDP falls and the economy moves from peak to trough. But the longer that process takes the more likely it is that business investment will falter and you can see that potential output falls after some time (as investment tails off).

As a result of the lack of new productive capacity, potential outfall shrinks and as recovery slowly unfolds it never reaches the old potential growth path.

The estimated costs of the recession (and any lack of fiscal support) are thus huge and result in permament income losses to the economy (and workers).

Implications

The implications are clear.

Governments should do all they can via spending and job creation programs to stop the economy sliding into recession.

And when the non-government sector, for whatever reason, reduces spending growth, the government has to be agile and meet the spending gap with fiscal policy expansion.

Otherwise, the recession becomes deeper, the recovery longer and the permanent damage astronomical.

The IMF authors acknowledge that “if hysteresis is relevant” then:

In the context of optimal policy this means that taking early and aggressive policy action can minimize the effects of other shocks and therefore help offset the permanent damage they cause.

They conclude that:

1. “Stabilization policy should try to offset the damaging impact of an adverse shock as fast as possible during a recession.”

2. “if policy makers are too conservative and act too early on the fears that the economy is overheating they might, via hysteresis effects, negatively affect the supply side and shorten the expansion.”

3. “running the economy as close to potential as possible can bring large benefits …”

4. “Aggressive and fast action during recessions becomes optimal policy. And during expansions, the cost of acting too early on fears of inflationary pressure can also be very costly as it can either reduce the potential growth of the economy or hinder positive developments in the labor market.”

5. “If our economic policies are not aggressive enough, they could make the economic effects of the crisis even larger.”

Conclusion

In other words, the neoliberal arguments that typically constrain the size of government interventions and end stimulus episodes too early are not wanted now.

Governments should jettison their neoliberal biases and realise that they will have to run significantly elevated deficits for years to come if the real sectors are to show any semblance of recovery.

There is only one school of thought that provides a consistent framework to guide this process – Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

And aren’t the critics – those mainstreamers who are suffering attention deficit syndrome – lining up with their asinine attacks. Fun to watch really.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

All this is fine prof Bill, but ones gotta ask why do the voters keep voting for parties and candidates who harm them?

Gov. should try to avoid recessions only if they are controlled by the mass of the people.

If Gov. are controlled by the 1% then they should not try to avoid recessions, because recessions are good for the 1%.

I’m not an expert.

AFAIK, recessions have 2 causes. Well 3 if we count pandemics.

1] An economy that is dependent on consumer borrowing to keep the GDP growing is unstable because sooner or later consumers can’t borrow more because their income is not sufficient to pay the resulting monthly payments.

2] A gov. surplus sucks *income* out of the economy until the the people can’t make their monthly payments. n this case “people” refers more to small businessmen.

The facts that the 1% benefit from recessions and the 1% control the Gov.and economic rules and policies, are the PROBLEM. Bailing the 1% out just makes it worse. It make the 1% fear recessions even less.

IIRC, the 1% bought up the foreclosed houses for around 50% of their value. So, they doubled their wealth.

If this is so, then why would they get their Gov. to avoid recessions?

“A decade of slack labor markets, depriving generations of young workers of job experience, will damage the human capital stock ”

It damages the physical capital stock as well. You end up with businesses that set up their business models based upon the existence of cheap skilled labour. Then as soon as the market starts to dry up they are in trouble.

You seem to get the same effect when labour is subsidised at the low end by tax credit systems or other income supplement schemes.

Labour needs to be “reassuringly expensive” so that capital will always choose the automated option the first time around, rather than sinking capital into labour intensive processes that rapidly run out of people at the top of the business cycle – rendering the whole investment a waste of time and money.

If we want automatic car washes rather than people stood outside in all weathers with a bucket and sponge then we need to find alternative activities for the people so that it is worth installing the machines. Machines that won’t quit to get a better job when one turns up and which can be discarded and recycled when they get sick from being stuck outside in inclement weather for too many years.

“And aren’t the critics – those mainstreamers who are suffering attention deficit syndrome – lining up with their asinine attacks. Fun to watch really.”

Bootle in the Telegraph last night. It was a laughable piece where he essentially agreed with everything MMT says but then repeated the New Keynesian religious positions just to make sure he wouldn’t be thrown out of the priesthood. Even quoted Reinhart and Rogoff just to be sure.

The cognitive dissonance is strong with this one.

“In other words, the neoliberal arguments that typically constrain the size of government interventions and end stimulus episodes too early are not wanted now.

Governments should jettison their neoliberal biases and realise that they will have to run significantly elevated deficits for years to come if the real sectors are to show any semblance of recovery.

There is only one school of thought that provides a consistent framework to guide this process – Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”.

As someone who follows this blog and who tries hard to reflect (even inexactly) MMT policy-precepts in his thinking and writing (eg in letters to newspaper editors, local politicians) my efforts are continually negated by the fact that I live in a eurozone country.

Policy-advice being given to govt. here for post-crisis “recovery” planning gives the greatest priority to the need for “restoring sustainability of the public fiances” as quickly as possible. In other words “slam on the brakes, cut labour and social-security costs, achieve improved competitivity so as to boost exports”, and so on (aka full-out internal devaluation).

Although I strongly suspect that that would instinctively be the preferred policy of any Finnish govt even if the country were not in the EZ (because IMO of their lutheran, self-punishing, DNA) that’s just academic supposition, because the fact is that they’re not going to have the luxury of making their own choices anyway.

This (latest) IMF policy-guidance challenges every single feature of the Stability and Growth Pact and Fiscal Compact – which noises coming out of Brussels suggest the Commission is dead-set on reinstating in full – if not enhanced – force at the earliest possible juncture, ie perhaps as soon as with effect from 1.1.2022.

Unless the IMF’s counsel prevails over the Commission’s (aided and abetted by the diehard majority within the Eurogroup) power-play, the EU is already predestined to re-run the history of the post-GFC decade – only much worse.

That’s if it survives of course.

robertH,

The EU has a problem similar to America’s problem in 1786.

The US Gov. could not levy taxes and EU nations can’t have a deficit.

America solved the problem with the Constitutional Convention.

The EU could (but most likely will not) do the same.

That is have a Convention, propose new rules/treaties and take over the EU & EZ if about 16 nations want the changes. The rest can join later or go their own way.

This will not happen IMHO. Maybe because the 1% are doing fine the way it is now, and don’t give a heck about the welfare of the masses.

“the power to issue its own money, to make drafts on its own central bank, is the main thing which defines national independence” – Godley

A nation that cannot issue a draft on its own central bank is a colony, not a country.

I’m learning a little more American history : ‘The weak central government established by the Articles (of Confederation 1776-77) received only those powers which the former colonies had recognized as belonging to king and Parliament… On March 4, 1789, the government under the Articles was replaced with the federal government under the Constitution.[4] The new Constitution provided for a much stronger federal government by establishing a chief executive (the President), courts, and taxing powers.’ (wiki). Thanks Steve_A. Wish the powers that be would act as quickly these days, but that it hadn’t taken over 200 years to discover that too much power had been given to the Chief Executive.

Steve makes two important points in his comments above: (1) that in a financial crisis, federal bailouts primarily of the plutocrats insulate them from feeling and addressing the pain and desperation that impact the masses; and (2) that since the plutocrats have come to own and operate the federal governments, they can get away with limiting federal relief (apart from short-term emergency measures) largely to themselves. These fundamental points, so strikingly obvious in the United States, lead me to believe that the challenge for MMT is not so much intellectual as political, less a matter of changing the minds of the elite few than of summoning the political will of the non-elite many. Accordingly, IMHO, the sooner MMT is joined at the hip to socioeconomic demands to save people and planet, the quicker will it catch fire and become a vehicle for the evolution of our species, not merely a lens through which to observe its devolution. My hope is that the sequel to “Reclaiming the State” (which Bill and Tom are apparently about to launch) will lay out concrete applications of MMT to humanity’s most pressing social and environmental problems, offer a specific plan of action not only to see us through the impending Post-Covid Depression but also to provide a lasting and unifying agenda for ongoing progressive political change. Let’s face it–the JG is only a start and without more–a lot more–could as easily shore up the neoliberal social order as transform it. Albert Schweitzer, in distilling the elemental, universal value of “reverence for life,” said that its infusion/diffusion in hearts and minds was like a mother teaching her child to walk. Although she initially had to hold its hand and guide it, there came a point where she had to let the hand go if the child were to walk on its own. As I see things, Schweitzer and MMT in tandem have provided humanity with the necessary support and guidance to evolve, have sequentially put forward both the galvanizing ideal or goal and the practical mode in which it can be actualized or achieved in our sociopolitical life. Has not the time come for us to take these extraordinary gifts (the value of reverence for life and the insight of MMT) and begin to walk on our own? And should not that collective walking–how to move our feet, keep our balance, move forward together–become the overriding topic of our thought and conversation? Yet we still seem mired in dystopia, content to pour out endless, tiresome indictments of the status quo. Only when there is an unmistakable shift in the zeitgeist from dystopia to utopia, only when vivid and compelling visions of a better, more beautiful world take precedence over repetitive, depressing descriptions of our ugly, oppressive, and ecocidal one, will there be evidence that we’ve matured enough, become determined enough and strong enough, to take up the vexing but vital task of making our way forward as we must, in the only way we can…step-by-step.

That graph you drew could be used to illustrate the impact of a traumatic event on a person’s life. The consequences of trauma can also permanently reduce one’s potential. The and the longer it takes to deal with the underlying problem, the worse the long term consequences are.

Regarding the “v shape” it seems like it assumes that covid only has “one wave” of infections. Globally the virus cases haven’t peaked on the first wave yet. And this took 5-6 months. My guess is the deaths are coming down due to doctors learning how to better treat the virus – possibly also under reporting. If it is the peak today it will probably take another 5-6 months to reduce the peak. Then the recovery can start. This seems longer than a v shape over 2-3 quarters.

In the short/medium term we’re going to have problems with airplane travel – possibly a skills shortage in aviation coming up, as experienced workers change jobs? Or who knows? maybe VR technology will make travel obsolete?

Here’s an alternative take. For those at top it’s not a crisis at all, its a great bargain sale. So instead of looking at this through a physics lens like people are rocks, instead see the present based on future expectations (discounting). The economy isn’t just path-dependent, it’s also goal-oriented and competitive. The competitive note means that we don’t need to care about maximization as much, it doesn’t matter if our infrastructure turns to mush as long as it’s still better than the next person’s. The climb to the top can generate growth, but it can also harm growth (war) and it goes to show you that growth was never the point at all. Governments just need to make sure they don’t slip down the pyramid, it doesn’t matter how big the pyramid is. You could learn a thing or two from the finance bears.

Newton: the challenge now more than ever, is to somehow get through to Mr and Ms average, the key points of MMT, explained as simply as possible (not easy of course).

So, it only took the IMF more than 70 years to come around to Abba Lerner’s functional finance insights.

Progress of a sort, I suppose, if painfully glacial …

Tom, “The deficit will burden our children and grandchildren” is an incredibly powerful argument: it is easy to understand and appeals to common sense and personal experience.

That’s why the Job Guarantee program is an integral part of MMT economic policy proposal targeted at the dual problems any society faces, namely inflation and unemployment. In this respect the state acting as an employer of last resort would hire any unemployed persons willing to accept a living minimum wage. It is precisely through the creation of a pool of employed workers that the state would provide a sustainable solution to the dual problems of inflation and unemployment. The other two problems, that is the business cycle and economic growth, will also be taken care of as a by product of solving the former.

I recommend that we don’t use the term ‘idle labour’. I used it in a comment on a submission to the Labour National Policy Forum and the author dismissed everything I argued because she thought it implied coercion.

“an incredibly powerful argument”

This is one usage where I agree the word “incredible” is completely apt.

The argument is powerful, and

The argument misleads and people believe it at their peril.

I saw an interesting study at Facebook: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264999320312773

First, mainstream economics is getting familiar with hysteresis. Second, output hysteresis cannot be caused by employment hysteresis. Employment tends to return to the initial level, but output remains below the pre-recession trend. Third, the paper says: “Hysteresis dramatically increases the welfare costs of recessions & Hysteresis implies that stabilization policy should respond forcefully to recessions”. The conclusions (the paper is new Keynesian) is almost identical to that of Bill: “governments should do everything possible to avoid recessions. ” What is the difference?