I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Long-term unemployment rising again

I am currently researching (again) long-term unemployment and how it behaves. Neo-liberal economists typically consider long term unemployment to be highly obdurate in relation to the business cycle and thus a primary constraint on a person’s chances of getting a job. This was the assertion that underpinned the neo-liberal approach to labour market policy and which in Australia culminated in the privatisation of the public employment service and the establishment of the (failed) Job Network. It is one of the most disappointing aspects of current federal policy that the Government is intent of keeping this ideologically-driven supply-side approach going. While the Prime Minister continually claims that he wants to introduce evidence-based policy, his decision to retain the supply side neo-liberal approach to labour market policy fails the facts test outright.

The neo-liberal assertions were highly influential in the design of the 1994 OECD Job Study which influenced governments everywhere and led to the supply-side policy approach (and the abandonment of full employment). The principle claim was that long term unemployment possessed strong irreversibility properties. Irreversibility is sometimes referred to as hysteresis and suggests that the long term unemployed constitute a bottleneck to economic growth which can only be ameliorated through supply-side (rather than demand-side) policy initiatives.

After the previous federal regime in Australia introduced the Job Network and pursued “employability” rather than ensuring there were enough jobs available, the OECD considered these “market-based” developments to be the exemplar for other nations to follow. In 2001, the OECD praised Australia for its path-breaking lead in introducing “market-type mechanisms into job-broking and related employment services” The OECD concluded that in terms of labour market policies Australia “has been among the OECD countries complying best” with the OECD Jobs Strategy. The problem is that the facts never supported the decisions by the previous government to dismantle the public sector and privatise labour market programs. And they certainly do not support the current government’s apparent capture by the supply-side lobby.

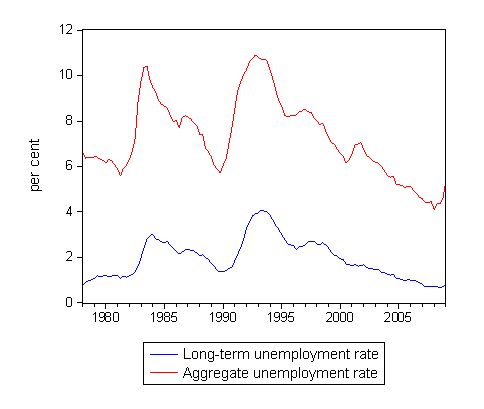

In earlier work that I have done studying the rise in long term unemployment I found no evidence that there had been any major structural shifts in the relationship between long-term unemployment and total unemployment. The sharp rises in long-term unemployment occurred as a consequence of the two recessions. In the first graph you can see this very clearly. The long-term unemployment rate (LTUR) rises with a slight lag with the official unemployment rate (UR). The lag is because it takes 12 months before a person who becomes unemployed today is counted as being long-term unemployed. So during a prolonged downturn, the flows into short-term unemployment feed longer duration spells of unemployment which then cascades over into long-term unemployment. All the dynamics of the LTUR are demand-driven. I have never been able to construct them as steady structural shifts driven by behavioural supply side changes.

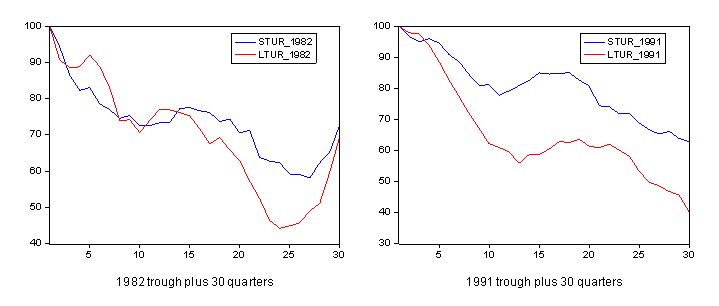

Is there evidence that the LTUR is resistant to growth as is claimed by the irreversibility hypothesis? The following graph shows the decline in the LTUR and the STUR from the unemployment peaks (trough of labour market cycle) coinciding with the 1982 and 1991 recessions, respectively. The observations are indexed with the peak observations being 100 and charted for 30 quarters following the peak. The short term unemployment rate peaks precede long term unemployment peaks, which in turn, lag the related troughs in Gross Domestic Product. Economic growth clearly provides job opportunities for both pools of unemployment. There does not appear to be any sequential accessing of the short term pool first as the irreversibility hypothesis would suggest. Indeed, following the 1991 recession, the long term unemployment rate fell much more sharply than the short term rate. In previous work I rejected the possible explanation that these patterns could have been due to labour force exit behaviour.

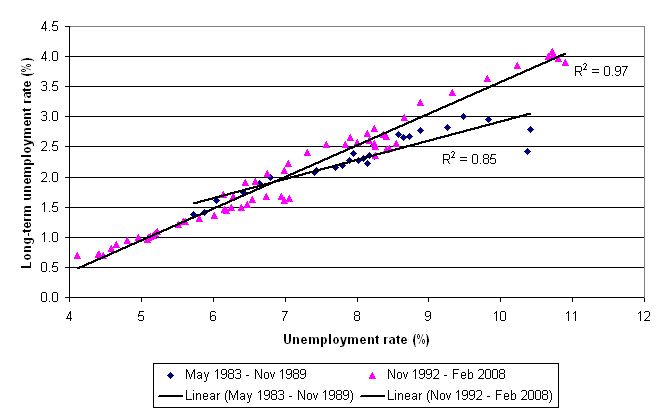

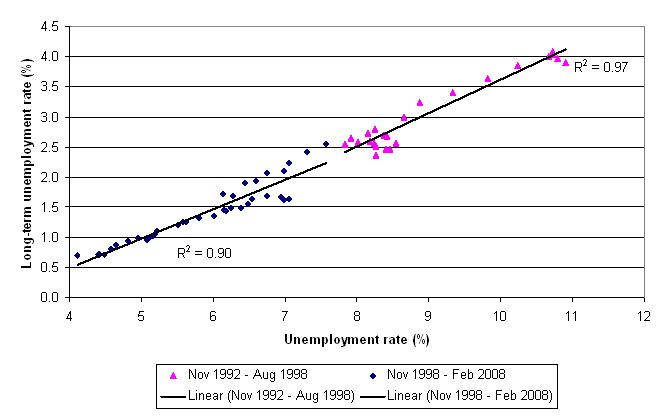

The next graph compares the relationship between the official unemployment and the long term unemployment rate for two recovery cycles coinciding with the peak of the official unemployment rate in May 1983 and November 1992 until the respective troughs were reached at the end of the cycle (November 1989 and February 2008, respectively). The black lines (and R2) are simple linear regressions for each of the two sets of (differently notated) pair-wise observations.

The graph confirms that the LTUR moves closely with the official rate as the business cycle improves. There does not appear to be any strong indication of hysteresis operating. The two recoveries are also strikingly similar so that the any notion that structural changes (or policy regimes) within the economy have increased hysteresis or that the period of Active Labour Market Programs in the 1990s have decreased it cannot be substantiated by this data.

To see whether the billions of dollars that were poured into the Job Network to “case manage” the long-term unemployed – allegedly providing them with intensive training and career support to make them more employable, I split the post 1991 recession recovery period into two: (a) the pre-Job Network period from November 1992 to August 1998; and (b) the Job Network period from November 1998 to February 2008 (the end of the growth cycle). The following graph shows the comparison between the two periods (the “policy-off” and “policy-on” periods). Spot the difference if you can! You cannot! The only minor change is that the relationship between UR and LTUR is slightly less precise in the Job Network period. It would have to show significantly closer relationship if you were to argue that the Job Network made a difference. So the behaviour of the relationship between UR and LTUR is indistinguishable between the two periods.

In the post 1998 period we see both lower URs and lower LTURs only because the rate of economic growth was maintained throughout the period which eventually brought them both down in lock-step! The secret is to keep employment growing. The Job Network did not create a single job (other than the jobs within the agencies themselves!).

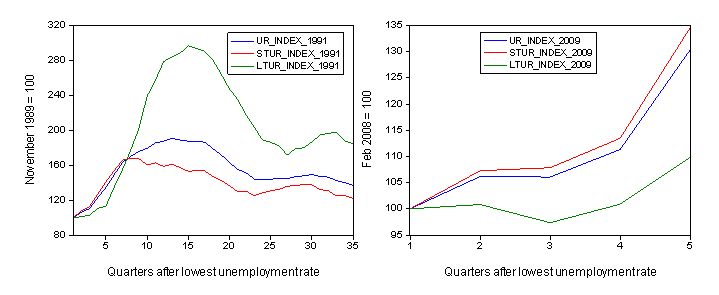

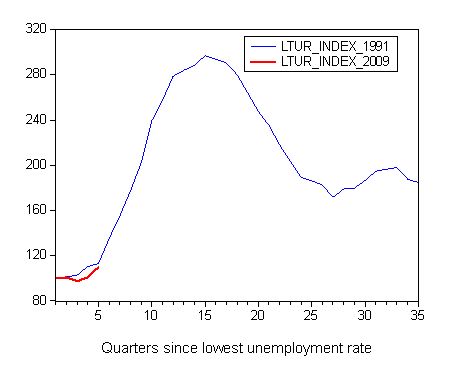

The following graph shows you how the three measures of unemployment rates move during a recession. The left-hand panel depicts the movement of UR, LTUR and the short-term unemployment rate (STUR – defined as unemployment spells less than 12 months as a percentage of the labour force) from November 1989 (the lowest UR reached prior to the 1991 recession) out to February 1999. The right-hand panel shows the three series since February 2008 (the lowest UR in the recent growth cycle) until February 2009. The graphs are index numbers (with the base = 100 at the lowest UR) and the horizontal axis is the quarters following the lowest UR quarter. The graph gives you a good idea of how the labour market behaves. Initially LTUR lags while the STUR climbs very quickly. If the government fails to attenuate the cycle and average duration of unemployment rises, you see the LTUR start to balloon even after the STUR has peaked. In the current downturn (still early days), the LTUR is just starting to rise.

Don’t be fooled into thinking that the LTUR is behaving differently this time to 1991. Remember the horizontal axis in the left panel is 35 quarters and in the right-hand panel only 5 quarters. The following graph shows the LTUR index in 1991 (blue) and 2009 (red) on the same horizontal scale. You can see things are now heading in the same direction as in 1991. This type of evidence demands early labour market intervention to stop the STUR from rising. If you stop that deterioration you stop the flow-on into long-term unemployment which takes years of growth to reduce (given that that labour force is growing continually). The best way to stop short-term unemployment from rising is to directly create public sector jobs! That again!

Conclusion

The results do not support the irreversibility hypothesis relating to long-term unemployment in Australia. The evidence suggests that when there is stronger labour market demand in the form of employment growth and accessibility both long-term and short-term unemployment are reduced. There is also no evidence that long-term unemployment is less sensitive to labour demand.

The results bring into question the effectiveness of the current Federal Government’s policy strategy which exclusively relies on active labour market programs and welfare-to-work initiatives to deal with the impacts of the recession. The fact is that when employment growth is not strong enough you will find persistent long-term unemployment.

My earlier work has shown that the usual demographic and human capital suspects are clearly present in regions with high long-term unemployment rates. So low levels of education; poor language skills; evidence of disabilities; etc. However, given that employment growth and localised accessibility to employment matter in determining the spatial patterning of unemployment, the ‘supply side’ variables operate to shuffle the rationed labour queue. In this regard, the less-skilled, lowly educated workers, for example, will be the residents who face long-term unemployment in these rationed regional labour markets. So the best the Job Network might have done was to shuffle the queue of disadvantage. Not worth the indignity that it forced on millions of Australians nor the billions that were wasted. It was an ideological exercise designed to punish the weak who were allegedly to blame for their misfortune.

As I said at the outset, the preparedness of the current government to perpetuate this insidious approach in denial of the overwhelming evidence against it, is very disappointing.

My Daughter Jane is a long term unemployed person, she has been on the personal support program but they have done little to help her. My daughter completed VCE has done a Cert 2 in Business Administration but has not worked for more than a few weeks for the last 3-4 years. I have tried to get her to try volunteer work to no avail. My daughter will be 26 in December and I don’t see her getting a job anytime soon. Fortunately my daughter lives at home she could not afford to live on her own.

Marilyn Hooten.

What help is there for my daughter.

Unfortunately Marilyn the support structures that should be in place, including direct public job creation are absent in this country. Our politicians choose to waste the lives of people such as your daughter rather than show leadership and provide them with jobs and embedded training.

best wishes

bill

Hi Bill – I came across your interesting article while doing some somewhat vague research into the relationship between longterm unemployment and volunteering. I have just completed some very localised research into our local voluntary and community sector, and I noticed from the figures that

“There is another aspect to this. From the figures given, 483 of respondents’ volunteers are unemployed, and 118 were recruited in the last year. One inference from that could be that quite a lot of volunteers are, in fact, long term. There could be some implications here. Does volunteering suit both the longterm unemployed AND the organisations they volunteer for, perhaps because for the volunteer it provides a structure, a place to socialise, and a sense of well-being from participating in the community and helping others, and for the organisation it provides consistent commitment and experience, both often vital to many activities in the voluntary sector? This relationship between being unemployed and volunteering could be a useful area for further investigation.”

However, what struck me from your work is how obvious your conclusions are, yet how difficult to get them recognised. There is some work recently published here in England, commissioned I think by the Local Government Association, which shows, if I have understood it correctly,that our underlying LTUR never fully recovers from the impact of each recession. This research may be of interest to you. If so, I’ll send you the link, if I can find it.

I don’t suppose you have done any research into volunteering levels in Australia?

cheers

John

Dear John

Thanks for your E-mail. I haven’t done any specific research on volunteering but have watched it grow over the period that high unemployment became entrenched. The last Federal government made a virtue of it claiming that it represented communities taking responsibility for themselves. My version of events is that it represented a loss of jobs (particularly public sector) but not essential functions as the neo-liberals attacked public service employment provision. So I have been anti-volunteers because they are filling this void and basically doing work for nothing that used to be done for pay. I am not attacking the individuals but the concept.

Further, for long-term unemployed workers who were over 55 years of age, the Government allowed them to fulfill their activity test requirements under our harsh unemployment benefits system by recognising volunteering. For younger workers, they had to keep a “dole diary” which meant they had to apply for 10 jobs a fortnight (even when unemployment to vacancy ratios were over 10!). But the government knew that the older workers were never going to get work but we part of the grey lobby (a powerful political force when it organises) and so they opted to allow them to do volunteer activity as a sign they deserved income support. It amounted to forcing a drastic pay cut onto them.

But I would be interested in any research about this from the UK. It is a phenomenon that interests me from both a labour market perspective but also from the political/ideological perspective that I note above.

best wishes

bill

Hi Bill,

How do you define long term unemployed. In the first part of the article I believe you mean (correct me if I am wrong) that the long term unemployed do not stand a chance of getting future employment. But then how come the long term unemployment rate shifts and becomes greater and lower at certain points. What happens to the long term unemployed at these positions as you said you don’t think it is because they are no longer regarded as actively participating in the work force. I hope I am making myself clear.

Also, I can see the correlation in your data between the long-term unemployment rates and it seams you have a point although I can’t determine exactley what the R values mean in that time period without associated P-values. It’s appears you may be onto something with this research.

If the recession goes a long period of time do you think the people that may become long term unemployed will have less of a chance of finding a job after the recession. I heard when/if it hits it may go for a while but I don’t know I think the media sometimes exaggerate and put a deliberate negative spin on things to keep people scared and working but I don’t know. I am a reasearch student and I have also kept my full time job because I am so scared of loosing it in these times. I keep thinking I am paranoid and have been brainwashed to do too much in fear of being unemployed.

K

Dear K

Long term unemployment is defined in Australia as being unemployed for more than a year.

The long-term unemployed are among those labour market groups that are seen as being undesirable by employers. So when there is an aggregate demand constraint on the economy and the excess labour supply queue is long, employers can pick and choose who they wish to employ. In that sense the long-term unemployed are at the back of the queue. However, when demand is stronger and employment growth picks up the queue starts to shorten and employers cannot afford to be as fussy. Then they take on who they can get and this includes the long-term unemployed. So the statements are consistent. It just means that the Government should always run the economy at high pressure levels to avoid the queue from lengthening.

If we do have a protracted recession then long-term unemployment will rise sharply merely because average duration increases.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

I understand what you are saying. Does that mean if a worker had a skill that was in high demand before the recession and the worker got sacked during the recession because that skill was no longer required, that means that the worker (even though being long term unemployed after the recession) will still stand a great chance of being employed after the recession if that skill in unique and now required. Does that mean to say that long term unemployed are always looked at unfavourably really depends on why the worker is long time unemployed?

K

Dear K

It all depends. The point is that when the labour market is tight firms will relax hiring standards and offer relevant training to ensure they get staff. When the labour market is weak, they will force the training costs onto the workers and pick and choose among them.

best wishes

bill

But what if the skills that the long term unemployed person had after a recession are scarce and the company cannot simply just resort to training future staff. Surely, this would mean that a person who was long term unemployed with a skill that was in high demand would have the same chance if not more of a chance of gaining employment after recession then somebody that was short term unemployed and have a skill that is not needed in the workforce. Dosen’t this mean that the chances of the long term unemployed person gaining employment over a short term unemployed person gaining employment as far as having an advantage really depends on the state of the labour market? rather then saying that long term unemployed people always are disadvantaged over short term unemployed people in gaining employment which is what you are saying?

k