These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

The British government did not approach insolvency in March 2020

Insolvency is a corporate term which refers to a situation where a company is unable to pay contractual liabilities when they become due. From a balance sheet perspective, it means that the assets are valued below the liabilities. The term cannot be applied to a national government that does not issue liabilities in foreign currencies. Such a government can always meet its nominal liabilities irrespective of institutional arrangements it might have put in place to create contingent flows of numbers from one ‘box’ (account) to another ‘box’. Those arrangements do not override the intrinsic capacity of the legislator. So when the British press went crazy the other day reporting comments made by the Bank of England governor that the British government was on the cusp of insolvency, they did the British public a disservice. Donald Trump would have been finally justified in accusing the media of pushing out ‘fake’ news.

As background, this blog post is instructive – On voluntary constraints that undermine public purpose (December 25, 2009).

The UK Guardian decided to go the ‘fake’ news path in its article (June 23, 2020) – Britain nearly went bust in March, says Bank of England.

The lurid headline clearly exercised the imagination of some copy editor or whatever they are called but doesn’t help the reader understand the situation that they were reporting at all.

The UK Guardian continued:

Britain came close to effective insolvency at the onset of the coronavirus crisis as financial markets plunged into turmoil

Note the term “effective insolvency” which has no real meaning anyway.

The interview that started all the hooha was aired as a podcast on the Sky News program The World Tomorrow (June 22, 2020).

The segment saw the “Ed Conway and Sajid Javid talk to Andrew Bailey about the Bank of England’s intervention at the start of the pandemic”.

Conway is Sky’s economics head and Javid is the ex-Chancellor.

Some of the early comments from the interviewers were ridiculous – like those relating to the Bank of England “running out of ammunition to fight the pandemic”.

The Bank of England governor appeared first at the 6:22 minutes mark.

The comments that set the media into a lying frenzy begin at 6:46:

You may remember in the first week, we basically had a pretty near meltdown of some of, some of the core financial market When you get to, I got to Wednesday afternoon, and the markets team came down here, and, in the afternoon. And you know it’s not good when they turn up, en masse. And you know it’s not good when they say we’ve got to talk, and it wasn’t good. We were in a state of borderline disorderly, I mean it was disorderly in the sense that when you looked at the volatility in what was core markets, I mean core exchange rates, core government bond markets, we were seeing things that were pretty unprecedented certainly in recent recent times, and we were facing serious disorder.

Of course it was clear why we were facing it in terms of what was going on outside in this unprecedented shut down of the economy, effectively that was going on.

At 8:02, Ed Conway asked “How scary was that? I mean what were the prospects if the bank had not actually stepped in”.

Andrew Bailey replied:

Oh I think the prospects would have been very bad. Oh, and by the way, I should say that the other major central banks were also doing very similar things and we were all closely coordinated. I think it would have been very serious. I think we would have had a situation where in the worst element, the government would have struggled to fund itself in the short run …

Obviously we had, there are things you could do at that point. It is not, it’s not outright failure in that sense We have got backup mechanisms that you can use.

Note – “there are things you could do”!

The UK Guardian article somewhat down the page admitted that “Although the government said the country would still have had options available” it still persisted with the lurid headline.

Conclusion:

1. Britain did not “nearly go bust in March”.

2. Britain as a nation cannot go bust.

3. It is not a corporation.

4. It is not a household.

5. The concept of a corporate balance sheet does not have any application to a currency-issuing government.

So what was this all about?

What the Bank governor was really talking about was the financial market disruption that emerged in the early days of the pandemic. It is clearly the role of the Bank of England to maintain financial stability in British markets.

That was where the uncertainty lay.

We need to understand the different ways in which governments work within the institutional arrangements they put in place around debt and payments.

For Britain, two types of debt are issued via auction:

1. Gilts – are typically liabilities issued by the government which promise to pay a yield (‘coupon rate’) at regular intervals and return the principle at the agreed maturity date (say, 5 years or 10 years).

There are other forms ‘undated gilts’, ‘index-linked gilts’ which have other characteristics but are less significant in the overall picture.

See – About gilts.

2. Treasury Bills – are “zero coupon eligible debt securities” that are typically issued “through regular weekly or ad hoc tenders”. The zero coupon just means that they are issued at a ‘discount’ but redeemed at the ‘par’ value.

For example, say the market yield for short-term debt was 10 per cent. A six-month treasury bill might have a par value of £100 (which is what the holder will receive on redemption).

So the discounted price that the purchaser of the bill at issue would be prepared to pay to the government would be £95.20 (don’t worry about how I calculated that – there is a standard formula and I assumed half-yearly compounding).

Treasury Bill can be issued for just 1 day and up to 364 days but usually they are for 1, 4 and 6 month maturities.

See – About treasury bills.

Treasury Bills are used to match short-run spending needs. The gilts market is less responsive to daily needs – the institutional structure surrounding the auctions, for example, doesn’t lend itself to instant flows of funds.

Under the voluntary institutional arrangements that the government has put in place via legislation and regulation, funds raised from treasury bill tenders are placed in an account from which the Government then draws on when it spends.

If there are contractual or political spending imperatives today, and the treasury bill account cannot cover the funds required then, from an institutional perspective, there is a funding shortfall.

And as Andrew Bailey went on to say – “there are things you could do” – which just refers, in one way, to the fact that the central bank can always fill these gaps for the Treasury department.

One pocket of government can always be replenished by the other pocket any time it chooses, institutional arrangements notwithstanding!

A few months ago there was a bit hooha about the so-called Ways and Means Account held by H.M. Treasury at the Bank of England.

I wrote about this issue in this blog post – Bank of England official blows the cover on mainstream macroeconomics (April 28, 2020).

Effectively, the ‘Ways and Means’ account is an overdraft that the Treasury has with its central bank that allows it to spend freely without satisfying the usual accounting and administrative practices (ex post) relating to treasury bill or gilt issuance.

On April 9, 2020, the British Treasury made this announcement – HM Treasury and Bank of England announce temporary extension of the Ways and Means facility – which told the public that the Bank of England would increase the available funds in that overdraft account if the Treasury needed to spend large sums quickly.

In other words, they can increase fiscal deficits without recourse to the markets ‘matching’ the deficits with debt-issuance any time they like.

We should note, of course, that government spending occurs in the same way, however these administrative, institutional and accounting conventions and practices are exercised.

The Treasury instructs the central bank to credit bank accounts in the non-government sector on its behalf.

Every hour of every day.

That is how spending occurs.

All these other administrative type conventions do not alter that fact.

On April 23, 2020, an ‘external member’ of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, gave a speech – Monetary policy and the Bank of England’s balance sheet – where he said that:

1. The Ways and Means account is used to smooth out “government cash flows”.

2. “Such a back-up is rarely needed except in periods of sharp unexpected deviations from the financing plan.”

Or, when there is severe disruption in the short-term money markets due to endemic uncertainty engendered by an event such as the coronavirus pandemic.

The Treasury bills market

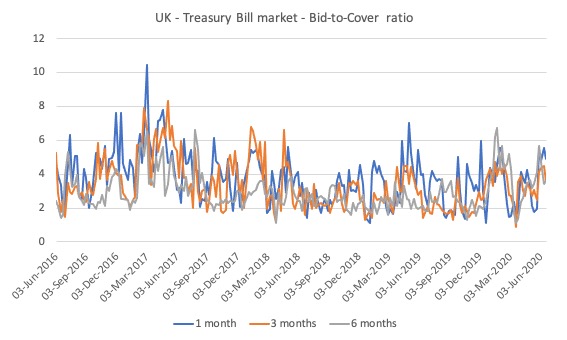

The following graph shows the bid-to-cover ratio for the UK Treasury Bills tenders from the beginning of June 2016 to June 19, 2020.

The bid-to-cover ratio is just the the £ volume of the bids received to the total £ volumes desired. So if the government wanted to place £20 million of debt and there were bids of £40 million in the markets then the bid-to-cover ratio would be 2.

The financial media are always predicting the ratios will fall as investors give up on buying government bonds

Over this period, the averages have been:

– 1 month bills = 3.76

– 3 month bills = 3.35

– 6 month bills = 2.95

So mostly, the tenders are strong.

However, occasionally, the demand for the tender can fall well below these average ratios.

So as you can see from the graph, the ratios fell below 1 to 0.87 for 3 month bills on March 20, 2020 but was at 1.56 for 1 month bills on the same day and 1.11 for 6 months bills.

And that ‘weakness’ disappeared by the end of the week, with the ratio of 3.55 in the following week for 3 month bills.

The point is that this behaviour reflected general market uncertainty rather than an assessment that the UK government was about to default on its liabilities or some other such sentiment that would stop the private debt markets from buying British government bills.

Later on in the interview, the Bank of England governor sought to clarify what he had said earlier given that clearly in the short-term bills market, except for the blip on March 20, 2020 in the 3 month bills, there was no question the ‘markets’ were willing to purchase British government bills across the maturity range offered (1, 3 and 6 months).

Andrew Bailey said his concern was really about “market instability” rather than whether the government would be able to ‘fund’ itself.

After discussing how extraordinary nature of the Bank’s response, he went on to say (starting around 18:49):

I was worried. And let me explain that because it is an important point. So I think one way, I think how would this have played out if we hadn’t taken the action that we and other central banks took? I think what you could have easily seen, would have seen actually a, a risk premium enter into interest rates, I think markets would have priced in a risk premium, and it could have been quite substantial given the degree of instability we were seeing. That would have raised the effective borrowing cost throughout the economy. Now, and that would have, in terms, in terms of the Bank of England’s objectives, that would have made it harder for us to achieve our objectives, both in terms of inflation and in terms of economic stability and economic growth that underlies that.

So it is clearly not in our interest to see that happen. Now the fact that the government, at that point in time, the government is the largest borrower – not the only borrower by the way because the corporate sector was borrowing quite heavily, the big corporates were borrowing heavily in anticipation at that point. But the fact that the government is the largest borrower is actually largely irrelevant to that argument about the risk premium and the increase in the effective rate of interest. So I don’t see that as compromising

our independence …

So, in effect the £200 billion intervention (the largest QE and quickest to be introduced in British history) was nothing to do with government funding requirements under the existing institutional structure.

It was about providing liquidity to the non-government sector to ensure interest rates didn’t spike, which the bank considered would make the economic consequences of the pandemic even more dire.

He wanted to stop irrational asset sales by wealth holders driving down prices and pushing up yields across the relevant maturity ranges.

In other words, insolvency fears had nothing to do with the Bank’s actions. It was a standard QE exercise to keep interest rates low and stable.

While we understand that the media is always trying to sensationalise things one should draw the line about fake and lurid beat ups!

The British media – progressive and otherwise should hang their heads in shame.

They missed the whole point of the interview.

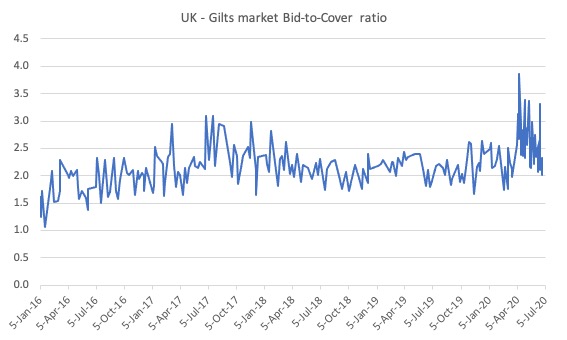

Gilts market remains strong

Further, if you look at the gilts market, the demand for longer-term government debt has remained strong throughout.

I wrote about the evolution of that market in this recent blog post – Britain confounding the macroeconomic textbooks – except one! (May 21, 2020).

Not a lot has changed since then in terms of robustness.

The bid-to-cover ratio is just the the £ volume of the bids received to the total £ volumes desired. So if the government wanted to place £20 million of debt and there were bids of £40 million in the markets then the bid-to-cover ratio would be 2.

The financial media are always predicting the ratios will fall as investors give up on buying government bonds.

Here is the record of bid-to-cover ratios in the British gilts market from January 5, 2016 to the latest gilt auction on June 24, 2020.

Even in the early days of the pandemic, the demand for gilts was strong.

I still get sent blog links or papers written as sorts of ‘gotcha’ moments – in the ‘ah, I have you now, you stupid MMT cultists’ tradition that has evolved, which tell me that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is plain stupid because it is obvious there are financial constraints on governments as evidenced by these institutional arrangements.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

The point is that MMT makes it clear that there is a difference between the intrinsic capacity of a currency-issuing government in a fiat monetary system and the capacities that they render for themselves through their legislative and regulative volition.

Refer back to the blog post from 2009 where I discuss that in detail.

The difference between the intrinsic state and the state on the ground at any point in time reflect ideology and political choice.

And by exposing that difference, MMT brings the public a long way forward in understanding than if they remain in the world of mainstream macroeconomics which alleges the institutional reality is the intrinsic monetary reality.

Thus blurring the ideological element and covering up a whole raft of lying behaviour by governments who do not want to undertake certain policy options.

Conclusion

The important point is that legislation and regulation can be changed by the majority government.

The British government could always change any of the voluntary arrangements it has set in place and, for example, instruct its central bank to ensure any spending demands have financial integrity irrespective of what numbers appear in different accounts (gilts, treasury bills, tax etc)

It is very disturbing that the media misleads people so manifestly.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thanks for this contribution, I appreciate the details of the short-medium term funding technicalities of the government from a UK perspective.

I think everyone needs to look at the motivations of all the participants here. Clearly Sky News want an attention grabbing headline and “everything is in hand” is not that. Sajiv Javid was unceremoniously removed as chancellor when Johnson took over he is now free to be willfully ignorant to make the current executive look bad.

Andrew Bailey, whilst simply doing he job, is inevitably keen to be portrayed as the most important person in the country, “saving” the government and the economy.

Sadly these points will likely go unseen.

In March of this year the general public were so traumatised by the emerging health threat that they barely gave a passing thought to an emerging Government insolvency.

And they had already been through a proper financial crisis with the GFC of 2008 and were by now familiar with the inadequacies of the economic profession to either explain or eradicate the problem – indeed one of the most commended accounts of the credit default swap cataclysm was written by Gillian Tett, who is a Social Anthropologist.

“Under the voluntary institutional arrangements that the government has put in place via legislation and regulation”

Do you know what the legislation/regulation is specifically, because I’ve been unable to find it.

The National Loans Act 1968 1(1) states “The Treasury shall have an account at the Bank of England, to be called the National Loans Fund.”

12(7) explicitly states “The Bank of England may lend any sums which the Treasury have power to borrow under this section,”

Which means that government spending is funded simply by expanding both the National Loans Fund and the Consolidated Fund on either side of the balance sheet.

The whole charade of the Debt Management Account is referred back to 12(7) by “facilitating the raising of money under section 12 of this Act;”.

So the only restriction can be operational policy of the Treasury – not primary or secondary legislation. That seems to come from the ‘full funding rule’ first instituted in 1995 (a report issued under the watchful eye of a certain HM Treasury bod called Jonathan Portes…), and which is justified by.

“The rationale for the full funding rule is:

• that the government believes that the principles of transparency and predictability are best met by the full funding of its financing requirement

• to avoid the perception that financial transactions of the public sector could affect monetary conditions, consistent with the institutional separation between monetary policy and debt management policy”

AFAICT, the UK government has not statutory bars, only ideological ones.

“Andrew Bailey, whilst simply doing he job, is inevitably keen to be portrayed as the most important person in the country, “saving” the government and the economy.”

Seems to be.

There’s a piece on Bloomberg from him with the immortal words “But elevated balance sheets could limit the room for maneuver in future emergencies.”. I wish somebody would force him to explain how.

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-06-22/andrew-bailey-central-bank-reserves-can-t-be-taken-for-granted

FT Tuesday: “UK government almost ran out of funds, says BoE governor “. I’m in contact with the Chief Economist at TUC – I’ll send him this blog.

‘UK government almost ran out of funds’ says wilfully ignorant or inflated ego BoE governor – ‘I am the boss of the independent Bank of England, charged with looking after my constituents, the other lesser banks that depend on me, and if the elected government of mere people want me and my constituents to lend it money, they should ask deferentially’.

“The point is that MMT makes it clear that there is a difference between the intrinsic capacity of a currency-issuing government in a fiat monetary system and the capacities that they render for themselves through their legislative and regulative volition. …The difference between the intrinsic state and the state on the ground at any point in time reflect ideology and political choice.” Here, Bill succinctly hits two key philosophical points of MMT: (1) that the money of a currency-sovereign state is fiat money created merely by federal investment decisions; and (2) that federal rules and regulations, especially those pertaining to central and other banking, are arbitrary limitations which obfuscate and obstruct the first point. I thought it rather amazing that a recent interviewer of Bill wound up “justifying” point (2) by admitting that the people had to be kept in the dark about point (1), or they would demand too many social improvements from their federal governments. Worse yet, “weak and untrustworthy” politicians might then actually do what the people demanded. I ask you, was the enmity between neoliberalism and democracy–indeed, between neoliberalism and truth itself–ever more clearly revealed than in the stunning conclusion of that interview? Bill’s talked about this on his blog, of course, but I think we’ve only scratched the surface of the significance of this admission, forced to be made explicit and public by the cogency of Bill’s work and MMT in general.

Dear Bill. First of all thank you for his magnificent blog. On a Spanish website called “Nothing is Free”, with a neoliberal tendency, an article was published entitled “The Myth of Modern Monetary Theory” (https://nadaesgratis.es/admin/el-mito-de-la-teoria-monetaria -modern emnde stated the following: ..the myth of the MMT is to consider that an excessive increase in the monetary base can only generate high inflation for real reasons, such inflation being controllable.On the contrary, the reality is more similar for these policies to lead to a loss of confidence in the country’s currency, which materializes, both domestically and internationally, the risk of currency substitution and, therefore, generates an inflationary scenario for monetary reasons. Such inflationary scenario would be extremely difficult to control and, even more, to reverse, since trust is something hard to achieve and very easy to lose.

Could you comment on that. Thank you

Listening to the national broadcaster here in Canada, is like listening to a person with a split personality these days too.

The main interruptions to the near non stop coverage of the pandemic news, are the growing racial conflicts in Canada and the US, and most recently emerging, and, yet another round of fear mongering surrounding Canadian bond ratings being down graded by Fitch, following the IMF recent comments about it’s predictions of shrinkage greater than the international average of the Canadian economy; caused by the growing deficit and measures instituted by the government to mitigate effects of the pandemic.

Who do you call to put a stop to this? The government won’t act out of fears that it is interfering with media, and the talking heads from academia just fan the fire.

The bank of Canada allegedly uses a foreign private financial firm to assist it with monetary policy, but who assists the government navigating this?

Only an informed public can force change, and yet the resistance to the simple logic supplied by MMT in general is lead by those one would expect to know better.

“which materializes, both domestically and internationally, the risk of currency substitution”

With whom? To exchange a currency you have to have somebody coming in the opposite direction. What do they know that you don’t? Isn’t that just the market working?

For one currency to go down *all* the other currencies have to go up – which damages their exports and stops their “export led growth” engine. (Unless you believe they all have monopoly power to impose price rises – in which case why isn’t competition working?). Why would exporters allow that to happen when all they have to do to restart the engine is buy the currency and stick it in a draw somewhere or on the asset side of the central bank (hi China) /convenient “sovereign wealth fund that can never be drawn down” (hi Norway)?

Additionally if there is “currency substitition” then you generally have a saver swapping for a spender – who buys exports in the target country. That triggers the continuation of the spending chain, which triggers autostabilisiation from both the taxation side (via the additional transactions) and the job guarantee side (via the increased private employment to service the export side and the multiplier from that).

So where’s the problem? Particularly if you ban your central bank ever getting involved in the FX market and give it the power to demand the banks call in any loans in its currency that are used for currency speculation. (A 100% margin call).

But it’s good to see that the critics of MMT are on the last “currency crisis” hill. And which will be the one they die on.

“Particularly if you ban your central bank ever getting involved in the FX market and give it the power to demand the banks call in any loans in its currency that are used for currency speculation. (A 100% margin call).”

Should have added there: these set expectations in the FX market about how the central bank will behave towards those trying to attack the currency. Do expectations not work now either?

“Donald Trump would have been finally justified in accusing the media of pushing out ‘fake’ news”.

And by no means for the first time, alas. Like the proverbial stopped clock, *even* the egregious Trump can be right some of the time.

Googling “Frances Coppola – Britain was not “nearly bust” in March” will take you to her (comprehensive) dismissal of the “story” as well as her own scathing condemnation of the mendacity of the crowd responsible for spreading this piece of fake news. (And she’s not SFAIK in agreement with MMT!).

“The British media – progressive and otherwise should hang their heads in shame.

They missed the whole point of the interview”.

Absolutely!

And so should a certain self-appointed oracle (who shall be nameless) – only more so, because he purports to be an exponent of MMT. (But I forgot – he tells his adoring echo-chamber repeatedly that he knows everything, and anybody insufficiently deferential that they are “wasting his time”, then bans them).

Correction:- for “deferential” read “conformist”.

“purports”

Definitely. Try “a person’s contribution to society is the hours of effort they expend for the benefit of others, not how much cash they transfer to the Exchequer” and receive a megaban.

“I thought it rather amazing that a recent interviewer of Bill wound up “justifying” point (2) by admitting that the people had to be kept in the dark about point (1), or they would demand too many social improvements from their federal governments”. (Newton Finn)

Didn’t guru Samuelson as long ago as the ‘sixties (?) admit much the same thing? “Plus ça change…”

BTW who was the recent interviewer, and when (I’ve forgotten)?

Robert, you can listen to the interview as it moves toward its jaw-dropping culmination by searching YouTube for the following: “Podcast with Alan Kohler and Professor William Mitchell.”

Pedro at 2:54

I have tried to find previous blogs where Bill has already addressed your question.

Try this one “Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101”.

It sounds like the authors of the article that you linked do not understand MMT very well.

A few years ago Warren Mosler was attacked in the press for claiming that savings rise when the government runs a budget deficit. Have you seen the latest graphs of the federal budget deficit and savings? Enough said about the traditional school of economics.

Pedro@ 2:54

When I first look at the point you post, I mainly saw it from the MMT’s lens, so I agree with the previous comments offered on the article (and disagreed with the article).

However, it just occurred to me that Spain is in the European monetary union, hence, she is a currency user. Thus, the authors of the article have a very valid point.

Thus, in this case, I would agree with the author of the article, that it might drive up the interest rate in the country, and the feared inflation.

But not so much on the currency front, as I don’t think it is relevant here.

(However, at the moment, it seems that the European central bank is willing to buy unlimited amount of bonds from its member states, based on a recent interview I listened to, hosted by Bill talking to a German economist, based in Berlin. So, the fear is not so much a fear after all, at this moment in time).

Have a nice weekend!

In relation to Neil Wilson’s earlier comment about what the UK government’s powers are:-

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/11/section/19

19 Reserve powers.

(1)The Treasury, after consultation with the Governor of the Bank, may by order give the Bank directions with respect to monetary policy if they are satisfied that the directions are required in the public interest and by extreme economic circumstances.

(2)An order under this section may include such consequential modifications of the provisions of this Part relating to the Monetary Policy Committee as the Treasury think fit.

(3)A statutory instrument containing an order under this section shall be laid before Parliament after being made.

(4)Unless an order under this section is approved by resolution of each House of Parliament before the end of the period of 28 days beginning with the day on which it is made, it shall cease to have effect at the end of that period.

(5)In reckoning the period of 28 days for the purposes of subsection (4), no account shall be taken of any time during which Parliament is dissolved or prorogued or during which either House is adjourned for more than 4 days.

(6)An order under this section which does not cease to have effect before the end of the period of 3 months beginning with the day on which it is made shall cease to have effect at the end of that period.

(7)While an order under this section has effect, section 11 shall not have effect.