I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

Latest instalment in Project Fear is not very scary at all despite the headlines

A short blog post today – being Wednesday. I am still catching up on things after being away for a few weeks. The British Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) offered its latest contribution to Project Fear this week with their claim that the fiscal response to a no-deal Brexit would “would send government debt to its highest level in more than half a century”. Sounds scary. Which, of course, was the intention. That is what Project Fear is about. Creating illusions of disaster to discipline the political debate in a particular direction. Nothing new about that. But the media, including the UK Guardian had lurid headlines such as – No-deal Brexit would ‘push national debt to levels last seen in 60s’ (October 8, 2019). But if you think about it the worst case estimates are hardly anything to worry about, even if we took the estimates seriously and were concerned about movements in public debt ratios for a currency-issuing nation (which I am not). Here are a few graphs so that all my British friends can come from under their bed covers and face the day with a smile as the No-Deal data gets closer.

The IFS issued a press report (that was published as an Op Ed in The Times) –

This is not the time for tax cuts or spending increases (October 8, 2019) – which carried the news:

Leaving without a deal – even with minimal disruption – would push up borrowing to about £100 billion, or 4 per cent of national income. Debt would climb to almost 90 per cent of national income for the first time since the mid-1960s. Any support to the economy to weather a no-deal exit would push up the deficit still further, at least for a few years.

What the lurid headlines and reporting didn’t focus on was that even the IFS was not predicting an extended recession as a result of Brexit.

In terms of Brexit deal, they forecast above potential growth over the next three years, a strong catchup in private capital formation and steady private consumption expenditure.

Exports are also predicted to rise.

Where are the headlines about that?

And with a no-deal Brexit, growth is positive overall for the 2019-22 forecast horizon with business investment and exports recovering after the initial shock (what they call a “near-term recession”).

They also assume that there would be no real shortages of goods and services and there would be no acceleration in inflation.

And what of that “near-term recession”?

GDP is predicted to decline by 0.4 per cent over 2020.

Compare that to the GFC when GDP declined by 5.8 per cent between the June-quarter 2008 and the March-quarter 2009.

So the biggest shock in the last 50 years only leads to a decline in 0.4 per cent and even then the estimates of the decline are based on an assumed (very) modest fiscal response (stimulus).

If I was the British Treasury I would be introducing a stimulus to accompany a No-Deal Brexit more than twice the assumed intervention by the IFS.

Then it is likely that there would be no decline in Real GDP at all.

Further, as part of the UK Guardian’s sponsorship of Project Fear, here is a classic example that would be great for introductory statistics classes on the misuse of statisticals and graphs. For other examples see – Misleading Graph.

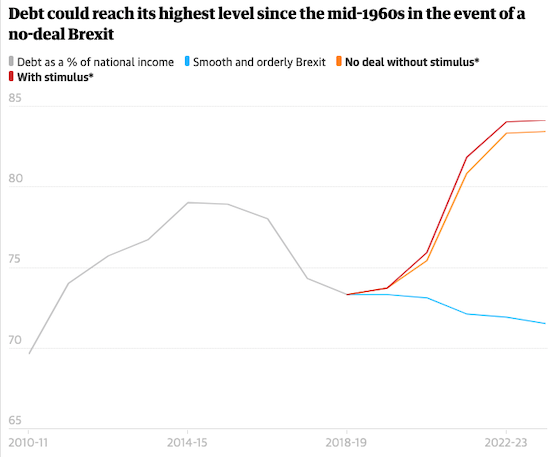

Compare the UK Guardian’s graph that follows for the different public debt to GDP scenarios and my graph that is below it.

Guardian graph

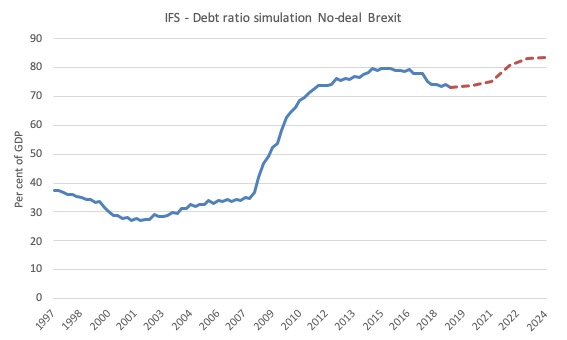

My graph

I only extrapolated the No Deal Brexit with Fiscal Stimulus estimates from the IFS.

The Guardian’s crooked graph is deliberately fudged (via the vertical axis adjustment) to make the rise in the debt ratios look massive. Most people are less aware of how mislead they are by pictorial or graphical information.

If we look at my graph with the complete vertical scale and no maximum value compression, we can see the upturn in New Debt as a percent of GDP is very small compared to say what happened as a consequence of the GFC.

If this is the worst the IFS can come up with then the scale of the deterioration is miniscule compared to the sort of estimates that were around a few years ago.

And, moreover, their fiscal intervention assumptions are very modest indeed.

Of course, all this is moot.

The public debt ratio in Britain, as a currency-issuing government, should not be considered a policy target. As long as the British government persists with pre-1971 institutional practices – matching its deficit with debt-issuance – which is now unnecessary in the fiat currency era – the debt ratio will fluctuate with economic activity and fiscal policy shifts.

Such fluctuations are irrelevant to the purpose of fiscal policy – to promote full employment and equity.

As a final reflection on the IFS Report, I note they analysed the Labour Party Fiscal Credibility Rule in the same exercise and concluded that:

Labour’s FCR has two key targets. The first – a rolling forward-looking target for the current budget … might well not prove robust to a no-deal Brexit: it is possible that a no-deal Brexit might mean that it is no longer an appropriate (or effective) constraint.

Labour’s second target – to have public sector net debt lower as a share of national income at the end of the parliament than at the start – has less to commend it. It is also incompatible with the programme of nationalisation and boost to investment spending proposed in Labour’s 2017 general election manifesto.

Which despite what all the ‘insiders’ have been claiming, the Fiscal Credibility Rule will fail during a recession and also will hamper the stated Labour Manifesto.

Labour has to understand three things:

1. The Fiscal Credibility Rule is a dud – it is ‘old technology’ – an artifact of the now failed Monetarist-New Keynesian ideology and should be scrapped in favour of a full employment and equity rule.

2. Adherence to the ‘Rule’ is incompatible with Labour’s Manifesto. They either scrap the Rule or present a new, more realistic but highly constrained

Manifesto.

3. Membership of the EU is incompatible with the Manifesto pledges. So they should be supporting Leave or abandoning key features of their Manifesto.

I know I am a worn out record on these issues, but now other groups are starting to say the same thing.

At some point, the Labour Party will have to change tack – one hopes they can do that before it is too late, although I sense they have received such poor advice in the last few years, particularly the Shadow Chancellor, that the horse might already have bolted.

Clarification

Several people have written to me about the recent publication by Real-World Economics Review – Modern monetary theory and its critics.

For the record, the editors approached me some time ago to contribute and claimed that the volume would represent the state of the art and authoritative go to source on all things Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

I declined the invitation and pointed out that the sort of MMT critics they had already published in previous editions, indicated to me that their editorial standards were lacking.

I also noted that there were already authoritative MMT sources available – to wit, 25 years of scholarship by the core economists associated with the MMT Project.

I concluded that there was no need for them to try to cash in on the growing popularity of our work.

Given the quality of the publication, I am glad I declined to participate.

Music today …

If you do not like funk then move on today.

Yes, it is time to move away from your desks and chairs and do it!

The New Orleans band – The Meters – were one of my favourite bands in the 1970s. They had everything – a big Hammond organ sound, a very sharp Fender Stratocaster sound and a fabulous drummer (Zigaboo Modeliste).

Here is one of their original instramental tracks – Cissy Strut – which was released on a single in 1969. I bought the single not long after that.

With the Neville Brothers involved it was hard to go past the band.

For a time in the early 1970s, everyone wanted to play funk to cure the ‘jazz rock’ addiction that had taken over guitarists.

I still listen to The Meters – still very groovy – 50 years on.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I am not remotely excited or otherwise by what the debt ratio is going to be post-brexit. It’s a number that has a minimal impact by itself on the UK economy. It’s impact will be psychological – that is our Government will go round panicking when it reaches some arbitrary threshold, and then go and do something stupid, not as monumentally stupid as the last 9 years perhaps, but stupid none the less.

I am much more interested however, in just how ready this Government is for what comes afterwards with a no deal exit, and they do not exude confidence, or competence for that matter. And competence is much more important. They seem rather to be suffering from severe myopia, which is a feature of just about every Government Department, not just Brexit per se, but to what is going on in the country as a whole.

And what they are about to embark on, if we exit with no deal will be by its very nature complex, and will take a great deal of time to resolve, because the first thing that the EU will talk about (after what we owe them), will be the Irish border. Worryingly the first Withdrawal Agreement, largely came into being, because the Government Ministers involved refused to listen to their own chief Ambassador to the EU, and this Government doesn’t show any signs that they are more receptive to advice from people who might actually know what they are talking about. Expect a stalled negotiation.

Meanwhile…

We have adverts entitled “Get Ready for Brexit” which is a master piece of non-information. Anyway you can go off to read the Government advice to business for trading with the EU in the event of a no deal exit.

And there are some interesting things, such as needing to apply for an international road hauliers licence, which is OK, except that the site also tells you that this is the rules now, but that after the 31st they will update the information… so you might need one, you might not, you might need something else… in other words our Government does not know what the exact position will be after the 31st for exporting goods to the EU by road.

And then there is export licences, which businesses will need, and it helpfully advises you that filling out an export licence is very complicated, and so you might want to think about paying somebody to do it for you.

Except when you think about… and there are people who will specialise in export licences, and I was wondering… do you think anyone has thought about whether there will be enough of these people to meet the possible demand?

Very unlikely in a Government that believes in the power of the market… if my business was filling in export licences, I would right now be looking very carefully at my fees, and wondering just by how much I could put them up, after the 31st October.

One of the things I took away from reading why Minsky matters is how the glut of savings that was produced by the economic growth after world war 2, was one of the main reasons why the new deal financial regulations were rolled back.

There was a glut of savings looking for better returns. The only way to get better returns was to destroy the safety nets put in place after the financial crash of the 1920’s. The famous stability creates instability that Minsky was known for. Only induces bank innovations that ultimately require lender of last resort interventions and even bailouts that validate riskier practices.

Which for me backs up the MMT case that we should not issue debt at all.

It’s not the economic effects of a No Deal Brexit which should concern us.

The debt ratio only fell a small percentage during Tory reign. All that ravaging austerity and suffering for a measly decline. 20 years from now history books will look back at this period like we look back at the Nazis and ask how this madness was made possible.

In addition to those that Bill identifies in the Y-axis, there is one further selective manipulation of the facts: i.e. the Graun’s restriction in the X-axis timeline to a starting point of 2011/2, as opposed to Bill’s at 1997. This also deceptively exaggerates the (estimated) post no-deal increase.

Even an X-value that started in 2007 would offer a more honest comparison in its depiction of any increase in public sector debt as a proportion of GPD, by fully indicating how little an increase a no-deal scenario would create compared to the massive increase caused by the GFC.

But what can you expect? These days, the Graun is just about worth a glance to see if there’s been an earthquake, flood or volcano somewhere. Or perhaps the untimely death of a famous person.

Once established that there hasn’t, the discerning reader would be well advised to move on…

@ Mark

The answer to your question (I am Intl Air Freight Forwarder) is no the industry does not have enough trained staff and neither do companies who only export/import to/from the EU.

Export licences are a particular problem. Depends which one you need but any dual use type licences are controlled by SPIRE which is a department of the DTI. Currently that process takes around 3 weeks so the question is do they have enough staff and that’s a big no. Gets even worse for other types of licences handled by other departments as a lot of these are not currently required within the EU.

From SPIRE’s website –

“HMRC’s Chief [computer] System is currently experiencing problems which is resulting in delays in the transfer of SPIRE data to CHIEF. HMRC are aware of the problem and are working to correct it. Please bear with us at this time.”

I have privately discussed this with Andy, and I think CHIEF (Customs Handling Import Export Freight) is going to be a big problem because it just isn’t capable of what will be a doubling of its use following a no-deal Brexit. The computer system was supposed to have been replaced several years ago but, guess what, it is over budget and delayed.

Bill,

There’s no catchpa today.

@Nigel

The replacement is called CDS (Customs Declaration Service) and it’s in a bit of a state by all accounts. Migration to it has been put back to September 2020 (from originally August 2018) it’s currently only live for a few ‘warehousing entries’ wont bore you with details of those but its a very small % of what is needed.

Last update we had was back in July and it is failing most tests.

“the horse may have already bolted”, or they may have simply revealed whose bed they’re really in.

so just don’t sell more treasury securities than you want to?

Everything in the blog may be correct but the problem in the UK is that there are no economists in the country who have any grasp of MMT and there are precious few politicians with much between their ears either. As you’ve been saying for ages, the UK has all the tools and resources to handle the transition. I also have all the tools and resources in my garage to make a Chippendale chair but it ain’t gonna happen. All I make is firewood. We have a government of retards hell bent on investment in our infrastructure to make it attractive to US takeover. You may call it Project fear but I’m afraid of trade deals with US exposing us to lower food standards. Yes, I’m afraid because although remaining in the EU may be bad (in your opinion) it’s going to be a bed of Roses compared to Brexit under a Tory government. A Labour government is most unlikely with the right wing propaganda machine of the press and the BBC and even if they got in power they’re utterly clueless and when the next financial crash comes they’ll get the blame. Yes, a golden opportunity awaits any party with a prepared mind but we don’t have that in the UK. Things are just going to get worse.

Bill. I’m not quite so hard as you on RWER. I visit their site. I didn’t even know they presumed to publish something on MMT and their critics. I’d be interested in a study of their critics: Who they are. Who they studied (MMT people & books). How much they know. What have they said. How much have they said. What motivates their attention and response. What is the quality and nature of their response? Come to think of it, a study of your critics is best done by someone without. That limits the perception of a defensive reaction. Not from all, but I’ve seen some respect for our work there. And I believe one Prof teaches some of it.

Was wondering if somebody more knowledgeable of NIPA is able to explain NZ’s recent fiscal policy observations to me?

The govt apparently collected a 7.5 billion dollar surplus, however this was somehow comprised of a re-valuation of NZ rail assets (the value is a political football) and part of NZs accrual accounts. At the same time I think it recorded a 0.5 billion dollar deficit on its cash flow.

Can someone describe how the 7.5 figure matches up to the govt deficit in the GDP statistics, and if it does how a revaluation transfers savings out of the non-govt sector in that case. My guess is the cash flow accounts fit into GDP calculations and we see two different accounting basis being described as the govt surplus (deficit) in this case.