My friend Alan Kohler, who is the finance presenter at the ABC, wrote an interesting…

IMF changes tune on industry policy – shamelessly – Part 1

In 1975, Tony Benn, a Left Labour member in the British Parliament and Secretary for Industry, proposed an alternative industrial plan to revitalise British industry. At the time, the Prime Minister and Chancellor were becoming attracted to Monetarism and started framing and implementing the austerity-type fiscal strategies that are common today. Benn opposed this approach, and, instead proposed a far-reaching alternative economic strategy that involved increased industrial planning to revitalise British industry. The growing ‘free market’ orthodoxy at the time, spearheaded by the IMF and the World Bank, which had transformed into neoliberal enforcement agencies, were vehemently opposed to any form of industry policies or state intervention. As a result, Benn was basically shut out of the debate and this helped transform social democratic politics into the mess it is today. Ironically, now the IMF is changing its tune. It has recently rediscovered how effective industry policies of the type Benn was proposed actually can be if supported by coherent policy structures. Irony two is that these supportive policy structures are the opposite to those typically proposed by the IMF. At the time, there were economists (such as yours truly) who knew that the descent into neoliberalism would be a disaster and hamper growth and more equal distributions of wealth and income. But that view was also shut out. Now, without shame, the IMF are basically admitting the decades of insufferable neoliberal policies that they forced onto nations may have been wrong. Industry policy is back in focus. Imagine if they never had seduced the world with their snake oil. British politics, for one, would have been quite different. Brexit could very well happened in 1975 under a Labour government. And more. This is Part 1 of a two-part series which will finish tomorrow.

The past

I have previously provided extensive analysis of the key turning points in history when social democratic political parties, usually when in government, adopted what we now consider to be neoliberal stances.

See the collection of blog posts under the – Demise of the Left – category.

These turning points are significant because the dominant actors at the time presented the situation faced by the nation in TINA terms even when there were clear alternatives each time.

The first really significant turning point was when the British Labour government used the IMF as an external authority in act of depoliticisation to smash those opposing its turn to the ‘free market’ economics that was gaining dominance in the academy and central banking institutions at the time.

I discussed that period specifically in this blog post – The 1976 British austerity shift – a triumph of perception over reality (June 13, 2016) – which provided further analysis of the British currency crisis in 1976 that led the Labour government to retreat to the IMF later in that year.

I traced the way the leadership of the British Labour government were building the case for austerity and the path they followed leading up to the request to the IMF for a stand-by loan. Far from being the only alternative available, the course taken by the Government was a triumph of ideology and perception over evidence and reality.

Constrained by its ideological predilection against any form of capital or import controls, an aversion to depreciation – the so-called ‘great unmentionable’ – and a fear that using central bank funds to match the fiscal deficit would cause inflation, the British Treasury formed the view that the nation was in collapsing unless it approached the IMF for funding.

Even though the currency was now floating, the hangovers from the Bretton Woods system, and the conflation of the level of the pound with some patriotic symbol of British greatness, were as strong as ever.

Peter Browning, who was the Treasury’s chief media officer at the time, later wrote that (page 12):

… open advocacy of devaluation was … the next worse thing to publishing obscene literature.

The quote actually was extracted from an Op Ed article written by the late LSE economics Professor Alan Day in the Observer.

(Reference: Browning, P. (1986) The Treasury and economic policy, 1964-1985, London, Longman).

He was referring to the Wilson Government’s first period of office in the 1960s under the Bretton Woods system where the deep reluctance to formally devalue the obviously overvalued pound was a major feature of the travails he encountered in that period of office.

But the same cultural aversion to allowing the pound to adjust downwards in times of overvaluation persisted into the floating exchange period, even though the ‘market’ would have sorted out the value rather than entering a process where the government had to seek permission from the IMF to adjust the parity as was the case under the Bretton Woods arrangements.

While the Chancellor in 1976, Denis Healey was pushing the standard Monetarist narrative straight out of the mainstream textbook, as if it was the only choice available to the Government, there was, in fact, a strong competing vision for Britain.

Healey had made substantial spending cuts in his April 1975 fiscal statement, and, in February 1976, he announced further cuts, which were supplemented in a so-called ’emergency package’ in July 1976.

Further, even though the Bank of England had introduced monetary targets in the early 1970s (the first to attempt to apply Milton Friedman’s doctrines) and failed, Healey reaffirmed that the Labour government would seek to control money supply growth. He clearly had drunk the Monetarist Kool Aide.

The use of the IMF by Healey had no basis in economics. It was designed to scare the bjesus out of the British people and disenfranchise the alternative policy proposals that the Labour Left were developing.

As I have noted previously, on March 24, 1975, Tony Benn, then the Secretary of State for Industry, sent the Prime Minister a document outlining the alternative path, which was based on such policy changes as import controls (particularly on luxury items), and a national plan to invest in and revitalise British industry.

Prime Minister Wilson annotated the document in this way:

I haven’t read, don’t propose to, but I disagree with it.

Groupthink.

You can see the actual document in the blog post cited above.

Wilson had also tried get rid of Tony Benn from this position as Secretary of State for Industry, which would have given Benn no latitude to propose such a wide-ranging industry policy.

Benn was considered a problem within the Party, intent, under the guidance of Healey and Wilson’s successor, James Callaghan, in shifting to a neoliberal stance and abandoning its historical Socialist platform.

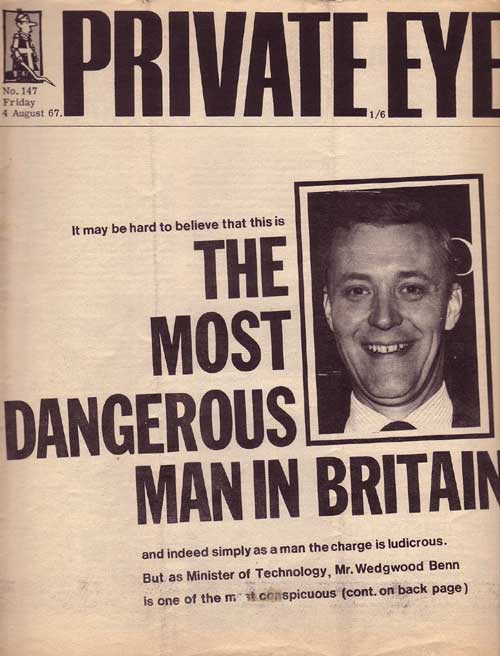

Here is the front cover from the Private Eye magazine, published on August 4, 1967.

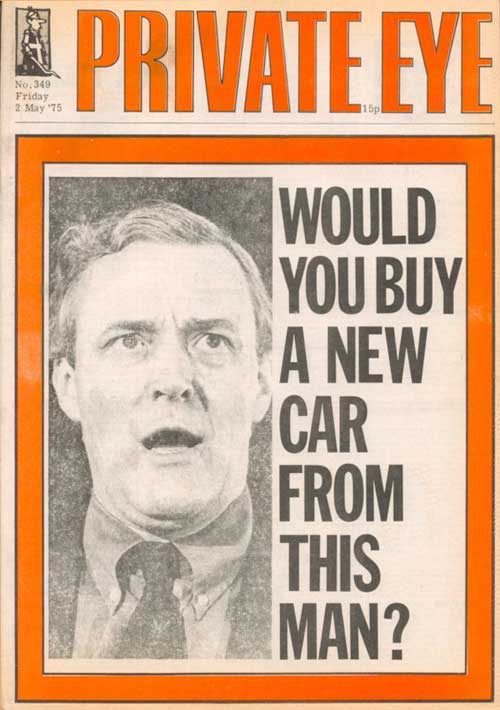

And at the time that Healey and Co were working to discredit him in the eyes of the public and within the Labour Party, Private Eye published this front cover (May 2, 1975).

Tony Benn’s alternative economic strategy, the so-called – Alternative Economic Strategy (AES) – rejected the Monetarist-inspired austerity that Healey was inflicting on Britain.

Instead, he proposed that Britain revitalise its industry with a sophisticated industry policy and provide some degree of protection to allow the initiatives time to take effect.

The AES included (see Bob Rowthorn’s article in Marxism Today, January 1981):

1. Fiscal stimulus to expand production and employment.

2. Import controls.

3. Price controls – to stop firms exploiting the import controls and pushing higher margins.

4. Compulsory planning agreements between government and multinational firms to align investment, production and employment decisions with national interest.

5. Nationalisation of key firms.

6. Public ownership of major banks to divert investment to advance public interest.

7. Less restrictions on trade unions to advance the interests of their workers.

8. Brexit!

9. Broadening of the Welfare State.

10. Cuts in military spending.

11. Policies to reduce wealth and income inequality.

(Reference: Rowthorn, R. (1981) ‘The Politics of the Alternative Economic Strategy’, Marxism Today, January, pp.4-10 – Download.)

In brief, the AES was an impeccable example of an alternative to the growing submission by social democratic political forces to the power of global capital.

It was rejected outright by the British Labour cabinet in December 1976.

This blog post, however, is not intending to provide an in-depth analysis of the AES.

The point that I am making by introducing its historical context is that its rejection was a direct result of the neoliberal attack on regulation, public ownership and any sense of planning, including trade protection, capital controls and industry policy.

All these strategies were deployed at various times in the Post World War 2 period to better align the inherent greed of capitalists with national interests.

In Europe, for example, prior to the introduction of the euro and before the Single European Act, the use of capital controls were the main reason there was any semblance of currency stability between the Member States.

There were regular currency crises as the Member States tried to achieve the impossible – tie their exchange rates when their respective economic structures were incompatible to such an objective. But capital controls helped reduce these crises.

The Single European Act, which came into operation in July 1987, forced nations to abandon the use of capital controls.

At the time, mainstream economists were claiming that capital controls were ineffective and undermine efficiency. The argument was always curious – either they were ineffective or they were not.

But the point is that the mainstream economists deeply opposed the use of capital controls and the IMF led the charge.

I wrote about capital controls in these blog posts (among others):

1. Why capital controls should be part of a progressive policy (July 6, 2016).

2. Are capital controls the answer? (April 28, 2010).

I discussed how, after decades of denial and inflicting massive damage on less developed nations as a result of that denial, the IMF finally began to embrace the effectiveness of capital controls.

Those blog posts document that capitulation from the IMF.

Now imagine what would have happened in, say, the 1980s, if Jacques Delors was confronting a hostile IMF as he plotted to introduce the Single Market and prevent Member States from using a key policy tool that was protecting their domestic economies from exchange rate speculation.

Imagine, if the IMF had been arguing, as they do now, and as Tony Benn was arguing in the 1970s, that nations had to temper the greed of global capital by regulating capital flows.

History would have been different and perhaps the Member States would never have bought into the euro snake oil.

Which brings us to industry policy.

The IMF and industry policy

In its Post-Bretton Woods incarnation (post 1971), the IMF was implacably opposed to industrial policy interventions by governments.

It has bullied governments into abandoning planning frameworks, where policy initiatives would help domestic industries grow through public subsidies, tariffs, partnerships in R&D, etc.

In particular, import-substitution industrial development strategies were particularly discouraged and declined as the IMF forced governments to deregulate, privatise, impose fiscal austerity and eschew any sense of ‘picking winners’.

The new emphasis was on export-bias with free flow of capital (in and out) with the requisite domination of foreign capital in local ownership. The corresponding outflows of resources and income flows to foreign owners were lauded as being the exemplar of development as health and education spending was cut and environmental degradation accelerated.

Key historical shifts occurred in this time – for example, this is the point period when social democratic governments and political parties started to embrace neoliberalism and we know how that has ended.

On March 26, 2019, the IMF published a new working paper (19/74) – The Return of the Policy That Shall Not Be Named: Principles of Industrial Policy.

Now, we are reading that the IMF has conceded that industry policy interventions that were the basis of economic planning in the Keynesian era were highly successful and only stopped being so, in some cases, when fiscal austerity was imposed and trade controls were abandoned in the 1970s.

Conclusion

Quite an amazing denial of their past narratives, even though they don’t frame their new found enthusiasm for planning in that way.

This is another case of imagine what might have been had the IMF not been so ideologically blinkered as it was trying to reinvent itself in the 1970s once the Bretton Woods system, that defined the IMFs existence, collapsed.

We will examine this shift in IMF position in Part 2.

Events

I have added a new page (it is in the top menu bar) – Events – where I will update my upcoming speaking engagements, where they are open to the public.

My next speaking Tour will be in Britain in May. Go to the page for more details and I hope you can support the activists who are organising these events.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill,

“only stopped being so, in some cases, when fiscal austerity and trade controls were abandoned in the 1970s”

-> fiscal stimulus?

Dear Willem (at 2019/04/08 at 11:14 am)

Yes, thanks for the scrutiny.

Fixed now.

Great RvV last night by the way, n’est-ce pas?

best wishes

bill

It found an unexpected winner in Bettiol, but his talent is obvious, he’s just still quite young.

Sagan said his performance is not peaking yet, but also noted that a group with so many favorites has a disadvantage in that they’re all looking at each other, and that you really need a smaller group of say four good riders to get Bettiol back. To no avail. A good race indeed.

“Prime Minister Wilson annotated the document in this way:

“I haven’t read, don’t propose to, but I disagree with it. “”

The man was way ahead of his time- he could be any of many successful, somewhat famous, mainstream economists of today whenever they discuss what they think of as MMT. Did they give this guy a Nobel Prize back then? Maybe they still could- sounds like he deserves one. Seems to have all the prerequisites in order.

Bill, Tony Benn was never a Marxist but a formidable Utopian Christian Socialist. Like all true believers he eventually became disillusioned with Christianity and Labor politics. He saw the hypocrisies, betrayals and shortsightedness in his own party and the mainstream Christian church, as failures to bring about meaningful social and economic change. A pity he never got the opportunity to become Prime Minister.

Wayne

Bill, I enjoyed revisiting Bob Rowthorn’s 1981 article. Is Bob still researching and writing on Economics?

Regards

Wayne

It is well past time for governments to return to capital controls, though they will be fought always and everywhere by oligarchs who oppress their countrymen and loot their economies, stashing their ill gotten gains in bolt holes in London and New York.

In addition to capital controls, credit guidance is also overdue for a return.

Impressive collection of back issues of Private Eye! You must be a bit of a hoarder, Bill!

Great post full of substantial insights into the history of what we (those of us old enough) have lived through – a sort of 40-year laboratory experiment with most of us as rats.

Superb article, as always Bill, and about a period in which I was becoming politically more conscious, and remember reasonably well. However, I think there is a typo or editing error in your first sentence:

I think there is a verb, or possibly a clause, missing. Not to be a grammar nanny, but you may have accidentally missed out some important information here.

I’m a big fan of the late Tony Benn. But I don’t think he would have made a good party leader (or Prime Minister). He worked best as the party’s conscience and intellectual inspiration.

Bill,

at the very first sentence, something seems to be missing:

“In 1975, Tony Benn, a Left Labour member in the British Parliament and Secretary for Industry.”

Maybe “[…] Tony Benn WAS a Left Labour…”.

On another topic, I was very happy to find an interview with Stephanie Kelton in the liberal paper “Zeit” from Germany this weekend (obviously behind a paywall). Maybe it was the transaltion, but I sensed Stephanie was being rather conservative in her approach. Then again, it mght be the best approach when touching on the German debt & inflation angst.

The word is spreading and people are starting to listen to those who have been consistently right in their predictions over those serious guys in dark suits that say we can’t have nice things.

Very interesting, Bill. Looks to me like the working paper is a far cry from an official IMF position, so early days I guess. I can understand your frustration with the IMF, but I’m not sure why you’re not even a little bit pleased they may be showing signs of change… isn’t this what you want them to do?

“I haven’t read, don’t propose to, but I disagree with it. “”

This tends to be the response of certain mainstream economists to MMT doesn’t it?

Part 2 answered my question nicely, thanks!