In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

The conflicting concepts of cosmopolitan within Europe – Part 1

In the past week, the UK Guardian readers were confronted with the on-going scandal of wealthy British politicians and ‘peers’ receiving massive European Union subsidies under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The article (January 27, 2019) – Peers and MPs receiving millions in EU farm subsidies – recounted the familiar tale –

“Dozens of MPs and peers, including some with vast inherited wealth, own or manage farms that collectively have received millions of pounds in European Union subsidies”. The story is not new and this scandal is just a reflection of the way in which the development of the European Union has contradicted the idealism that the Europhile Left associate with ‘Europe’. As an aside, it would be telling, one imagines to map the EU payments (and well-paid job holdings) with Brexit support – one would conjecture a strong negative correlation. This is a two-or-three part mini-series on the evolution of concepts of ‘cosmopolitanism’ in the European context. It is part of work I am doing for the next book Thomas Fazi and I hope to publish by the end of the year. In this blog post, I introduce the conflict that is inherent in the European Union, and the way the Europhile Left has been seduced by a concept of cosmopolitanism that bears not relevance in the reality of modern Europe.

One of the recurring themes in the Brexit discussions and debates about the European Union from the Left perspective is this concept of cosmopolitanism.

The short version of the narrative is that the European Union exemplifies human aspirations for togetherness, to create a truly one world where all are equal and free.

The hope for universality.

The converse assertion is that those who support Brexit or the breakup of the EU are against these aspirations and are ‘particularists’, verging on xenophobic nationalism, ignorant of human potential, abandoning our responsibilities to a greater humanity beyond our shores.

The crude allegations that those who voted to leave the EU were ignorant racists were rampant in the period that followed the crisis.

Of a similar nature were the allegations in week one of the Gilets Jaunes uprising that no progressive should align themselves with this group because they were climate change denialists as a result of their protestations about the fuel tax levies.

Don’t these idiots know that they can’t drive around as much as before? I saw Tweets along those lines from people who were presumably totally unfamiliar with the roots of the Gilets movement and their circumstances.

The European cosmopolitanism emerged among the elite, intellectual class as a way of articulating what a ‘post-nationalist’ world might look like and how ‘Project Europe’ could be construed within the globalisation of capitalism.

It was a response to what the elites thought to be narrow-minded nationalism that they wanted to distance themselves from.

Some of these European dreamers considered the way the European Union has evolved to be in the words of David Harvey (p.531):

… the Kantian dream of a cosmopolitan republicanism come true …

[Reference: Harvey, D. (2000) ‘Cosmopolitanism and the Banality of Geographical Evils’, Public Culture, 12(2), 529-564.]

In his 1795 essay, Perpetual Peace: A Philosophic Essay. philospher, Immanuel Kant wrote (p.142):

The intercourse, more or less close, which has been everywhere steadily increasing between the nations of the earth,has now extended so enormously that a violation of right in one part of the world is felt all over it. Hence the idea of a cosmopolitan right is no fantastical, high-flown notion of right, but a complement of the unwritten code of law – constitutional as well as international law – necessary for the public rights of mankind in general and thus for the realisation of perpetual peace. For only by endeavouring to fulfil the conditions laid down by this cosmopolitan law can we flatter ourselves that we are gradually approaching that ideal.

[Reference: Kant, I. (1795) Perpetual Peace: A Philosophic Essay, George Allen and Unwin, London, Third Edition, 1917), https://oll.libertyfund.org/sources/1266-facsimile-pdf-kant-perpetual-peace-a-philosophical-essay-1917-ed/download]

This passage is held out as evidence the Kant was proposing an arrangement of nations that were previously enemies to disavow martial conduct and, instead, work together, as equals, to advance the common good of all their citizens, irrespective of which side of the border these people were born or resided.

And as David Inglis recounts (p. 737-38):

… the EU was presented both by its own officialdom and their intellectual cheerleaders as a – if not the – major source and promoter of ‘really existing cosmopolitanism’ across the world … The EU, it was argued, was both a model for how erstwhile warring states could put their bellicose past behind them and create a union of peaceful equals – the peaceable League of States envisaged in Kant’s cosmopolitan theory – and also the promoter par excellence around the world of a vision of human life characterised by democracy, observation of human rights and the rule of law … In other words, the EU was claimed to have brought into being and embodied the Kantian liberal cosmopolitan dream.

[Reference: Inglis, D. (2015) ‘The Clash of Cosmopolitanisms: The European Union from Cosmopolitization to Neo-Liberalization’, in PACO – Partecipazione & Conflitto, 8(3), 736-760. http://siba-ese.unisalento.it/index.php/paco/article/download/15590/13528]

I discussed the historical origins of the EU in the early chapters of my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – in some detail.

After three major conflagrations on the European continent since 1871, the European political leaders determined that the best way to avoid further tragedies (mostly between France and Germany) would be to tie these nations together pursuing a common goal – the so-called ‘European Project’.

In the immediate Post-War period, while the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC), the precursor to the OECD, was helping administer the reconstruction of Europe under the Marshall Plan, French statesman, Jean Monnet wrote that (p.228):

Efforts by the various countries, in the present national frameworks, will not in my view be enough. Furthermore, the idea that sixteen sovereign nations will co-operate effectively is an illusion. I believe that only the establishment of a federation of the West, including Britain, will enable us to solve our problems quickly enough, and finally prevent war. I realize how difficult it is – it may even be impossible – but I see no other solution, if we have the necessary respite.

[Reference: Monnet, J. (1978) Memoirs, Doubleday & Company, Inc., New York]

Monnet recounts the discussions he had with various nations about the creation of a “European Community” and how they typically encountered “national resistance … largely because there was no independent centre of decision” (p.281).

He argued that “mere co-operation that inter-governmental systems, already weakened by the compromises built into them, were quickly paralysed by the rule that all decisions must be unanimous” (p.281).

All the ‘international’ organisations that were in play – such as the League of Nations and the United Nations Organization, and the Council of Europe – all “had the same inbuilt flaw” (p.281).

He said the (p.281):

The international assemblies gavc themselves the appearance of democratic bodies, publicly expressing their peoples’ will: what was less obvious was that even their unanimous resolutions were nullified, behind their backs, by a Committee or Council of Govetnment representatives, any one of whom could prevent all the others from acting as they wished.

Grand statements were common at the time about uniting the peoples’ of Europe but the reality was something quite different.

Nothing was going to happen because there remained deep suspicions between the European states.

Cutting across the varying Franco-German ambitions, however, was the complication of the Cold War between the West (principally the US) and the communist states of Eastern Europe.

The US clearly wanted a strong Western European bloc to be formed and were hostile to Charles de Gaulle’s plans to exclude the English-speaking world in order that France might dominate any supranational organisation that would form, given Germany’s on-going shame after the War.

To advance his Kantian dream, Monnet instigated with others, what became known as the “functionalist” approach – a pragmatic alternative to the “draft constitutions championed by the ardent federalists” (p.282), which were getting nowhere.

The French foreign minister at the time, Robert Schuman issued a declaration on May 9, 1950 – The Schuman Declaration – which outlined the imperative of the European Project and first introduced the idea of a European Community of Steel and Coal (ECSC).

He wrote:

… the contribution which an organised and living europe can bring to civilisation is indispensable to the mainte- nance of peaceful relations … Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity …

With this aim in view, the French Government proposes that action be taken immediately on one limited but decisive point: it proposes that Franco-German production of coal and steel as a whole be placed under a common high authority, within the framework of an organisation open to the participation of the other countries of Europe …

The solidarity in production thus established will make it plain that any war between France and Germany becomes not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible.

So there were two concepts of cosmopolitanism advanced here, although it is difficult to say whether the likes of Schuman realised this at the time.

These two concepts are at odds with each other and have allowed for the neoliberal ideology and approach to dominate the more liberal, universal aspirations.

On the one hand, we had the typical Kantian view that Europe would provide for “a rights-based conception of citizenship and democracy, which when it applied to trans-national conditions, becomes a kind of political cosmopolitanism” (Inglis, 2015: 738).

This allowed Germany to be reinstated as a ‘citizen’ of Europe and gave it scope to develop its industry.

But, the functionalist approach to integration, which began with the pragmatic decision to create the ECSC (and a bit later under the Treaty of Rome, the Common Agricultural Policy), spawned a “a liberal-economic, market-based cosmopolitanism” (Inglis, 2015: 738), which constructed the Member States as economic competitors.

While the universal citizen concept and all nations are equal rhetoric of the Kantian cosmopolitanism provided Germany with a path back to European respectability, and thrilled the progressive Left who considered the internationalisation of political struggle to be a way to transcend the particularism of localism, the functionalist approach gave Germany a path to become a dominant economic force, an outcome that has dominated the way that the ‘European Project’ has evolved.

And I don’t mean evolved in a positive way. This economic domination, coupled with France’s cynical hopes that it would be able to dominate any supra-national creation and restore its sense of greatness, have combined to create the Eurozone disaster.

The current Europhile Left hold out the first concept of cosmopolitanism as their beacon and their hope that the European Union can be reformed to render it a progressive force that respects the democratic aspirations of the peoples’ of Europe.

What they don’t seem to have gleaned is that the second concept of cosmopolitanism that was built into the ‘European Project’ – the economic liberalisation – has morphed into something that is deeply resistance to any sort of reform.

Up until the 1980s, it was difficult to see how Europe would go further than the ‘common market’.

In 1972, the Governor of the Danish Central Bank said (quoted in my 2015 book, page 4):

I will begin to believe in European economic and monetary union when someone explains how you control nine that are all running at different speeds within the same harness …

What eventually allowed the ‘nine horses’ to be harnessed together was not a diminution in Franco-German national and cultural rivalry but, rather, a growing homogenisation of the economic debate.

The surge in Monetarist thought within macroeconomics in the 1970s, first within the academy, then in policy making and central banking domains, quickly morphed into an insular Groupthink, which trapped policy makers in the thrall of the self-regulating, free market myth.

The accompanying ‘confirmation bias’, overwhelmed the debate about monetary integration.

The introduction of the Monetarist-inspired Barre Plan in 1976, by French Prime Minister Raymond Barre, under President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, showed how far the French had shifted from their Gaullist ‘Keynesian’ days.

Across Europe, unemployment became a policy tool aimed at maintaining price stability rather than a policy target, as it had been during the Keynesian era up until the mid-1970s.

Unemployment rose sharply as national governments, infested with Monetarist thought, began their long-lived love affair with austerity.

The cosmopolitanism that all citizens and all nations were equal was being shredded quickly. The Europhile Left missed the boat completely.

The Delors Report (1989), which informed the Maastricht conference, disregarded the conclusions of earlier Keynesian-inspired studies of integration (which emphasised full employment and equity).

That type of thinking was no longer tolerable within the Monetarist Groupthink that had taken over European debate.

The new breed of financial elites, who stood to gain massively from the deregulation that they demanded, promoted the re-emergence of the free market ideology that had been discredited during the Great Depression.

The shift from a Keynesian collective vision of full employment and equity to this new individualistic mob rule was driven by ideological bullying and narrow sectional interests rather than insights arising from a superior appeal to evidential authority and a concern for societal prosperity.

And so the limited, liberal-economic, market-based cosmopolitanism that had marked the creation of the Common Market gave way to a much more virulent form of cosmopolitanism – a neoliberal Europe, which meant that the Kantian aspirations had to be expendable, even though the political narratives emanating from the European elites (including the Social Democratic elements) kept articulating these universal goals for humanity.

It was obvious that the ‘European Project’ was jettisoning any notion of democracy and citizenship in favour of a dog-eat-dog competitive world.

The narratives and grand statements were one thing but the reality was another. World apart. One in political spin and the dinner parties of the elites of Europe – continuing to hold themselves out as social democrats; the other in the brutal reality of Stability and Growth Pacts, austerity, the colonisation of Greece, the attack on the working class.

The tension between the cosmopolitan concepts

Returning for a moment to the Brexit and French uprising, it is clear that, in both cases, their are also regional splits within the population developing under neoliberalism.

One of the tactics that capital has always deployed against the ‘working class’ is that of divide-and-conquer’. The application of neoliberalism and its outcomes has reinforced this divisive element.

The Centre for Cities study (January 28, 2019) – Cities Outlook 2019: cities and a decade of austerity – leaves us in no doubt about the way in which neoliberal policies have hollowed out the regional areas and their cities in Britain.

We learn that:

1. “it has been local government in England that has borne the biggest burden”.

2. “there has also been a great deal of variation within local government as to the severity of these cuts”.

3. “British cities – home to 55 per cent of the population – have shouldered 74 per cent of the total cuts to local government’s day-to-day spending.”

4. “Cities in the north of England were much harder hit than those elsewhere in Britain … Seven of the 10 cities with the largest cuts are in the North East, North West or Yorkshire, and on average northern cities saw a cut of 20 per cent to their spending. This contrasted to a cut of 9 per cent for cities in the East, South East and South West (excluding London)”.

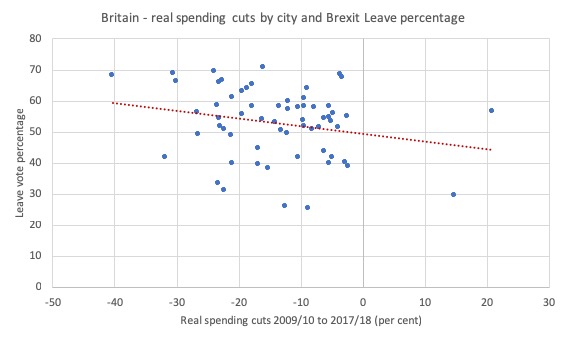

It is no surprise that areas such as Barnsley with a 40.4 per cent cut in real terms in spending between 2009/10 and 2017/18 voted 68.3 per cent to Leave in the Referendum.

I was curious about this and matched the real spending cuts by cities in the Cities Outlook with the Referendum result.

The following graph maps the relationship which is as expected – the higher the cuts, the more likely the Leave vote majority, although the relationship suggests other explanatory factors were also present.

The dotted line is a simple linear regression which suggests that the higher the real spending cuts the higher the Leave vote percentage.

I don’t want to labour this point because it needs a lot more analysis – but it is clear that outside London (Scotland and Northern Island), the Leave vote dominated the less affluent areas.

Similarly, the Gilets movement is a solid regional uprising.

This article in the offGuardian (January 27, 2019) – The Gilet Jaune and ‘France Profonde’ – written by an Australian musician and writer living in the South of France is worth consideration.

It explains the evolution of the uprising in the regional areas of France and the disregard the urban elites have for the France Profonde, an expression that relates to the essence of French culture and values – the ‘deep France’ – but is used perjoratively by the urban elites in Paris who look down on the regional citizens.

The urban elites think of the “Deep France” as extreme localism – while they are embracing the global world and its (neoliberal) culture.

Reading the offGuardian article we learn that:

1. In regional France, where “the towns display an obvious air of poverty, unemployment and civic decay … Support for the Gilets Jaunes is everywhere”.

2. “It’s an anger that’s has been building for a long time”.

3. “In a lot of ways their struggle is a struggle for movement, basic movement, entry level requirement movement like getting to work; the movement required to live in the most immediate sense. This is the social world of practices and everyday actions. It is not the world of globalist abstractions.”

4. While the elite urban progressives around the world decried the uprising, the reality is that the Gilets were against a “carbon tax for individuals” and wanted the burden of adjustment forced on the “polluters”.

5. They wanted “manufacturers to provide us with products that are not overwrapped, more ecological, more intelligent. Coherent and efficient public transport in our countryside”.

6. “these are the demands of an impoverished populace in rural locations, currently reliant on cars and with little income.”

7. Importantly, “France Profonde is also a revolt in the name of something positive, a vision of France as a place of equality, a place of valued parts, not one single globalised whole no matter how pure.”

I urge you to read the article in full as it provides a very different perspective of Europe than one will glean from the mainstream Europhile Left material that essentially says Europe needs some reform but must be protected and sustained.

That is not the view of the Gilets who reject the sort of cosmopolitanism that the elites pump out whether from the Right or the Left.

For the workers of Barnsley and the workers in the villages across the South of France, the struggle is about existence in a hostile environment marked by harsh austerity imposed by arrangements entered into by their politicians without regard for the distributional consequences.

In the French case, the Europhile voice of such people as Daniel Cohn-Bendit (of 1968 Paris riots fame) who now is a mate of Emmanuel Macron and condemns the Gilets as fascists.

The cosmopolitans of the 1960s who wanted to smash the state have now become the neoliberals of the C21st but continue the pretence of expressing a Left position.

Not all Member States are equal

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) exemplifies how the cosmopolitanism that drove the ‘European Project’ was flawed from the start.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) outlaid €58.82 billion to European Union farmers in 2018, mostly in income support measures.

This amounted to 37 per cent of the overall EU budget of €160,113 billion.

It is a large handout.

The CAP is also a good example of how ‘Europe’ conceives of the particular in its constant talk of convergence and integration.

The fiscal position of the CAP is under pressure and the next wave of changes will seek to cut the payments made to the agricultural sector across the European Union, particlarly if Britain exits.

Changes that have been mooted for the 2021 to 2027 fiscal horizon include moves to balance the handouts that farmers receive based on their land holdings.

Under the current scheme – outlined in the EU regulation – No 1307/2013 – “establishing rules for direct payments to farmers under support schemes within the framework of the common agricultural policy” – the CAP pays differential amounts to farmers based on their “eligible hectares” depending on when their Member State accessed membership of the EU.

Farmers in the new accession states (Central and Eastern Europe) are paid less per hectare than farmers in older Member States.

This was justified on the basis that the poorer Eastern European nations had lower land values and wage levels, in addition to other spurious criteria for differential treatment.

But the EU realises that:

Due to the successive integration of various sectors into the single payment scheme and the subsequent period of adjustment granted to farmers, it has become increasingly difficult to justify the existence of significant individual differences in the level of support per hectare resulting from use of historical references.

However, things are not going to be straightforward.

You can guess that farmers in Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark and elsewhere are vehemently opposed to this convergence process because with the total CAP budget under attack from the bean counters, farmers in these nations face the prospect of significant cuts to their handouts.

The quest for universality within Europe has always been compromised by local interests and always will be.

Conclusion

I will continue this theme in Part 2.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

There are additional lessons to be drawn from the shocking support for Guaidó’s coup attempt in Venezuela by the Europhile left in Spain whilst remaining absolutely silent about the gilets jaunes protests and the brutal police repression that Macron is using to quell the demonstrations. Maduro has mismanaged and economy that is totally dependent on oil exports and is collapse as a consequences of falling oil prices and production. There is no doubt about that. But he has been democratically elected. It seems like the European cosmopolitans use a different measuring rod for foreign countries governed by the left wing than the one used for the Neoliberal government of France even though the number of people killed, injured, maimed and arrested is much higher than what we are seeing in Venezuela.

“The cosmopolitans of the 1960s who wanted to smash the state have now become the neoliberals of the C21st but continue the pretence of expressing a Left position.”

This seems essential to me. They speak for the left but are not left when it comes to defending the disenfranchised . They are called neo-marxists or post-modernists, yet not many on the left grasp the reality these people sold out long ago.

Excellent read as usual.

I was having just this discussion over the weekend with friends you would describe as part of the “europhile left” (until not too long ago it would hold true for me as well). We ended up agreeing to disagree, though I acknowledge their fears of ultra-nationalist movements exploding around europe and the acknowledgged my criticism of their “Marie-Antoinette-Leftism” (which I thought was ingenious at the time but doesn’t look right all written out.)

In my opinion the “economic left” is played against the “social left” resulting in a false dichotomy in which one has to either embrace neoliberalism or cast aside the values of humanistic thought (big kudos for bringing Kant into the discussion!). This false dilemma is the reason why so many could possibly identify neoliberal technocrats like Merkel, Macron or Renzi as “left of the middle” politicians. Subsequently, most of those who strongly criticize them, the EU or even the neoliberal EMU are seen as reactionaries or anarchists.

As Bill and many others (Michael Hudson comes to mind) have pointed out, the neoliberal mainstream has won the “Deutungshoheit” (dominance in interpretation?) in the economical discourse by establishing not only the rules and framework but even redefining the language in which it is discussed. My absolute favorite in this regard is the redefinition of access to affordable healthcare, social services, retirement pensions and even education as “entitlements”. At the same time, measures that could best be described as “socialism for the rich/corporations” are called “reforms” and get nice-sounding names like “Agricultural Risk Protection Act” or “Troubled Asset Relief Programm”.

Additionally, their leading thinkers and personalities have succesfully managed to make themselves look like “very serious people” (well, BoJo hasn’t quite managed, but I can’t imagine he is even trying) when in reality they are mostly opportunistic careerists and grandstanders.

The double-shuffle around “entitlement” is even sneakier than that. By the dictionary definition (entitle: to give a rightful claim to anything) an entitlement is something you have a perfect right to receive, and if anyone denies it to you, they are stealing. Clever of the austerians to make us think that it’s some kind of frippery that we should be doing without.

Re the Guardian and xenophobia (hatred of foreigners) to which Bill refers, it is normal practice by Guardian journalists to attribute xenophobia and other forms of hate (e.g. as in “hate speech”) to all and sundry without so much as the beginnings of an attempt to prove that hatred is actually present or a motivating factor.

I reckon anyone who attributes “hate” to anyone else without VERY GOOD EXPLANATION is a nasty little nobody, and from that I conclude that most Guardian journalists are nasty little nobodies. Or perhaps I’ve missed something…:-)

Also worth reading wrt the Yellow Vests is:

communemag.com/yellow-vest’diaries

Good point, Mel. And now that you bring that up, I think there is even a third element to make it a triple-shuffle. The modern rentiers, the donor class, are often derided as “entitled” so one could consider the defamation of entitlements as a bit of “I’m not entitled, you are!” projection.

Hmm. Yes, indeed. Something I thought of later is a subtext that would deride that ridiculous underclass, strutting around as though they were nobility. So undemocratic of them, and so *un*deserved.

Caitlin Johnstone has been writing a series of essays describing control of narratives as a means to control public opinions. AKA propaganda. She’s not writing economics, but I see strong reinforcements and parallels with things bill writes.