I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

British growth strengthens in September quarter 2018

On Thursday (November 8, 2018), the British Office of National Statistics (ONS) released the – GDP first quarterly estimate, UK: July to September 2018 – data, the first release under their new publication model, which is designed to improve “the accuracy and reliability” of the initial (formally denoted the “preliminary”) release. The next update will come in December and the expectation is that there will be less revisions, which is a good thing for those trying to assess where things are at. Remember, also that national accounts data is a rear-vision view of the economy – where its been rather than necessarily where it is at, although the two ‘views’ are obviously linked. The third-quarter national accounts data shows that Britain grew by 0.6 per cent, with “all four sectors” contributing to what is a strong result. But, under the headline, are mixed trends: household consumption spending continues to grow with rising debt, although wages growth appears to be moving finally; business investment was negative; and net exports “contributed 0.8 percentage points” with a strengthening of exports. What the data tells us at this stage is that Britain continues to defy the claims that a meltdown is imminent as a result of Brexit. There appears to be a resilience that is driving relatively strong growth. And, for all those who have been hammering the point that Britain is the worst-performed (in growth terms) of the EU Member States, they will have to revise their scripts. Britain is now growing much faster than many other European economies.

Robust British growth in September-quarter 2018

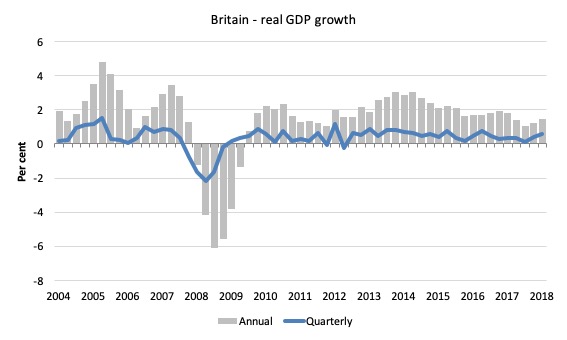

The quarterly growth in real GDP rose from 0.4 per cent to 0.6 per cent in the September-quarter 2018.

The economy has been steadily gaining strength since the beginning of the year – March-quarter 0.1 per cent, June-quarter 0.4, then 0.6 per cent in the September-quarter.

The annual growth rate is now 1.5 per cent and accelerating.

The following graph shows the quarterly and annual real GDP growth performance since the March-quarter 2004.

Much has been made of the recent – European Economic Forecast. Autumn 2018 – which was released on November 8, 2018.

The forecasts posited that the UK would be among the two worst performers for 2019 in terms of Real GDP growth, accompanied by the waning Italy.

I will have more to say about those forecasts on Wednesday.

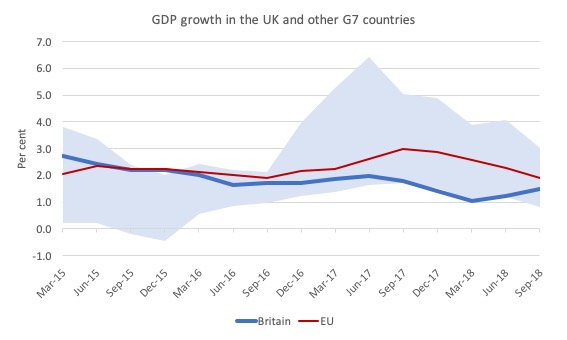

Also “Chart 1.2: GDP growth in the UK and other G7 countries” which was published in the – Economic and fiscal outlook – October 2018 – produced by the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR), shows Britain skating along the bottom of the G7 group since the September-quarter 2017.

That chart has been used by critics of Brexit to argue that Britain should have a second vote (or as many as are required to get the Leave option scrapped)!

I updated the graph with the latest data available from Eurostat, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Canstat and the Japanese Ministry of Finance to get third-quarter performance where possible (only second-quarter national accounts data is available for Germany, Canada and Japan).

The graph follows the format of the OBR graph, plotting the maximum and minimum annual real GDP growth rates for the G7 nations excluding Britain – this is the shaded area.

The blue line is Britain and I included the EU27 performance (red line) for comparison (especially as there is no third-quarter German national accounts data yet).

So things changed in the third-quarter. The maximum growth rate fell from 4.1 per cent (Canada in the June-quarter) to 3 per cent (US economy) although that might change when Canada reports its third-quarter results.

Clearly the EU27 is trending down while Britain has been trending up since the end of last year.

It is no longer the case that Britain is the tracking the worst-performed EU nation.

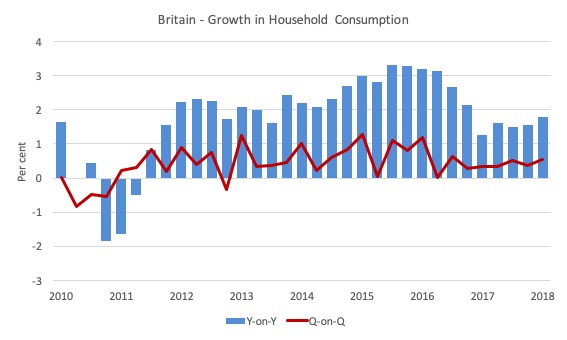

Growth in household consumption expenditure accelerated in the September-quarter (0.5 per cent up from 0.4 per cent).

The following graph shows the annual and quarterly growth since the March-quarter 2010.

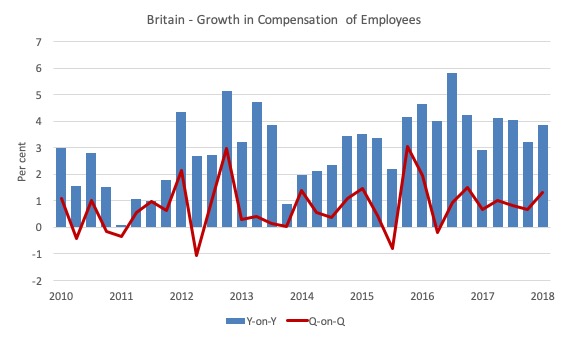

While this growth has been accompanied by an increase in household indebtedness, there was also stronger growth in compensation of employees (COE) in the September-quarter (1.3 per cent up from 0.7 per cent).

The following graph shows the annual and quarterly growth since the March-quarter 2010.

Business investment was disappointing, declining by 1.2 per cent for the quarter and 1.9 per cent in the 12 months to September 2018.

However, overall investment rose in the economy by 0.8 per cent in the September-quarter 2018 (up from -0.5 per cent in June), as a result of a strong boost to government investment (up 8.6 per cent).

The ONS inform us that

The 0.8% quarterly rise in GFCF was driven by a strong rise in government investment (8.6%), which was the strongest seen since Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2014 and reflects broad expenditure growth across central government, most notable in defence.

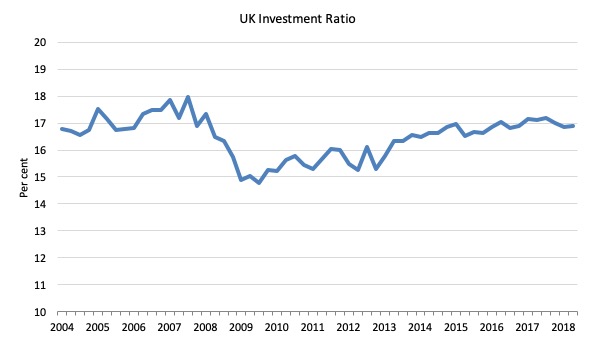

The next graph shows the UK investment ratio (total fixed capital formation as a percent of GDP) from the March-quarter 2005 to the September-quarter 2018.

The drop associated with the GFC is quite stunning. It went from 17.9 per cent of GDP in the December-quarter 2007 to 14.7 per cent by the December-quarter 2009.

That huge cyclical swing tells us how deep the GFC recession was in the UK.

But the current sluggishness does not bode well for future growth, given that potential GDP growth will be slowing as a result of the weak investment performance.

Investment expenditure contributes to aggregate demand (spending) now and builds productive capacity (supply) for the future.

The investment ratio, however, is at the same level as it was when the Brexit referendum was held in June 2016.

Finally, net exports were much stronger in the September-quarter 2018. Exports grew by 2.7 per cent (up from -2.2 per cent), while imports were static.

While the spurt in exports growth in 2017 (mostly as the exchange rate depreciated) is over, exports continue to generate record positive annual growth rates.

Contributions

What were the main drivers of growth in the September-quarter 2018?

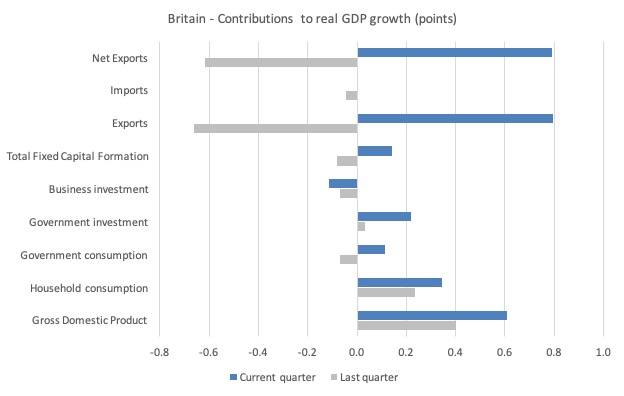

The following graph shows the quarterly contributions to real GDP growth (in points) from the major expenditure components for the June-quarter (gray bars) and the September-quarter (blue bars).

The standout is the export performance – contributing 0.79 points to overall growth.

Household consumption expenditure contributed 0.34 points to the overall growth.

The public sector contributed strongly to growth in the September-quarter 2018 – 0.33 points (as noted above the strong surge in defence infrastructure spending was notable).

The ONS inform us that:

Net trade made the largest positive contribution to GDP growth in Quarter 3 2018 (0.8 percentage points), driven by a 2.7% rise in exports, while imports were flat. The rise in exports is broadly consistent with external survey indicators which have remained solid, despite easing in recent months following a sustained period of strong growth. The export growth in Quarter 3 reflects an increase in both goods (4.4%) and services exports (0.8%), with goods exports to non-EU countries growing more robustly than to the EU. On a commodity level, exports of fuels and transport equipment performed particularly well in Quarter 3, with the latter being consistent with the strength seen in today’s production figures on transport equipment.

This is a sign that the export sector is already engaged in a shift in export markets in anticipation of the separation from the EU.

The same thing happened in Australia when Britain dumped up in the early 1970s by accessing membership of the EU. It didn’t take long for our export markets to shift to Asia away from the UK.

While the last graph captured the contribution of Gross Fixed Capital Formation, the ONS also present a Gross Capital Formation contribution, which:

… includes gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), changes in inventories and acquisitions less disposal of valuables …

This component subtracted “0.6 percentage points” from real GDP growth in the September-quarter 2018.

The ONS also tell us to be cautious about interpreting the business investment figures:

… today’s figures should be interpreted with some caution as early estimates of business investment can be prone to revision.

But it is probable, now, that “The recent subdued business investment environment is consistent with external surveys of investment intentions, which attribute much of the weakness to Brexit-related economic and political uncertainty.”

Productivity growth

How has the investment slump impacted on productivity growth?

While not part of the current National Accounts release from the ONS, their October 5, 2018 update of the productivity data is related to the investment slowdown. Note that this data only goes to the second-quarter 2018. The next update will be on January 9, 2019.

I analysed the productivity slump in Britain in this blog post – British productivity slump – all down to George Osborne’s austerity obsession (October 18, 2017).

I have updated that analysis today using the latest ONS data available – HERE.

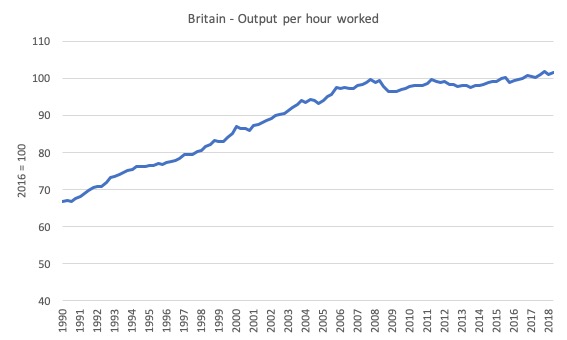

The following graph shows UK Whole economy output per hour worked from the first-quarter 1990 to the September-quarter 2018. The same sort of pattern emerges if we use the output per person employed measure.

The cyclical swings throughout this extended period are evident and the size of the GFC downturn is obvious.

The point is that British labour productivity growth slumped during the GFC, and, then stalled as a result of the austerity that was imposed in the aftermath of the recession.

A shallower slump followed and pre-dates, by some years, the Brexit referendum.

Further, in recent quarters, British productivity has actually been rising steadily and has consistently done so since the June 2016 Referendum, albeit at a modest rate.

Structural explanations of this slump are also unlikely to have traction. The massive cyclical contraction pushed British productivity growth of its past trend. Structural factors work more slowly and we would not witness such a fall if they were implicated.

Why would that cause productivity growth to slump then fail to recover?

A major driver of productivity is investment – both public and private.

While business investment is cost sensitive (so may respond to interest rate changes), mainstream economists usually ignore the fact that expectations of earnings are also important as are asymmetries across the cycle.

Cyclical asymmetries mean (in this context) that investment spending drops quickly when economic activity declines and typically takes a longer period to recover. So fast drop and slow recovery.

The cyclical asymmetries in investment spending arise because investment in new capital stock usually requires firms to make large irreversible capital outlays.

I discussed that phenomenon in detail in the blog post (cited above) – British productivity slump – all down to George Osborne’s austerity obsession (October 18, 2017) – which gives additional references.

The point is that when the economy experiences a sharp contraction, there is a necessity for strong fiscal support to rebuild confidence among firms that it will be worthwhile investing in new capacity.

Exactly the opposite happened in the UK with George Osborne pursuing his ideological obsession for fiscal surpluses (and failing).

Imposing pro-cyclical fiscal austerity of the scale that George Osborne initiated when the Tories came took government in May 2010 is the last thing a government should do when non-government spending is in retreat.

Fiscal austerity in these circumstances exacerbates the typical asymmetry associated with investment expenditure and is a major reason why business investment in the UK has been so weak.

We often focus on the short-term negative impacts of fiscal austerity, but in this case, it also has serious long-term impacts on both the rate of business investment and the potential growth rate (which falls as capital formation stalls).

The longer it takes for business investment to recover, the worse will be the long-term impact on potential GDP growth. In turn, this means that the inflation biases are increased because full capacity is reached sooner in a recovery – often before all the idle labour is absorbed.

So, while George Osborne is long gone, the negative impacts of his policy folly will reverberate for a long time to come. His failings will continue on for many years and the flat productivity growth is one manifestation of that failing.

Sectoral performance

The ONS write that:

Construction output growth continued to pick up following a weak start to the year, while quarterly output in the manufacturing sector rose for the first time in 2018. Growth in services output slowed to 0.4%, but remained the largest positive contributor to GDP growth in Quarter 3.

1. Construction was impacted by “adverse weather” earlier in the year.

2. “While output increased across all four main production sectors, around half of total production growth in Quarter 3 was driven by manufacturing … this pickup is … in line with the September reading for the Markit Manufacturing Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI), which saw an acceleration in output growth to a four-month high.”

3. “The recovery in manufacturing … was predominantly driven by transport equipment and specifically motor vehicle production.”

4. “In the services industries, output growth eased to 0.4% in Quarter 3 2018, contributing 0.3 percentage points to growth in GDP. This is in line with average rates seen since the start of 2017, following the relatively strong growth of 0.6% in Quarter 2 2018 …”

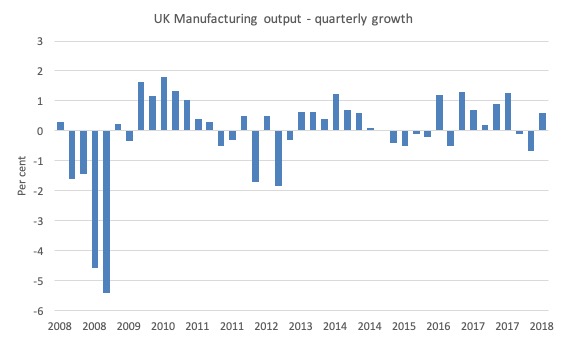

The following graph shows the quarterly growth in Manufacturing for Britain from the first-quarter 2008. Since the Brexit referendum, the sector has recorded mainly positive growth, although the slump earlier in this year was notable.

A reflection on our April 2018 Jacobin article – ‘Why the Left Should Embrace Brexit’

‘It was factually incorrect to say there was a GFC because economies are now growing’.

‘It was factually incorrect to say there was a Great Depression in the 1930s because by the 1940s it was over’.

That is the sort of logic that underpins the latest Twitter attacks against my work with Thomas Fazi.

Asinine is a euphemistic description of the behaviour exhibited again the weekend just gone by Tweeters intent on making fools of themselves in public.

On April 28, 2018, the Jacobin magazine published an article written by Thomas Fazi and myself –Why the Left Should Embrace Brexit.

The article generated an hysterical response on social media with various characters who profess to being progressive demanding that Jacobin withdraw the article.

I responded to those criticism in this blog post – The Europhile Left loses the plot (May 1, 2018).

You can also refresh your memories on the response from the European editor of Jacobin to the criticism they received from the ‘Left’ for publishing our view on Brexit.

He was, frankly, astounded with the vehement opposition to the fact that the article was published at all much less the views expressed in it.

He called it a “Bizarre” reaction that the Europhile Left would try to stifle open debate.

He said among other things, that “This kind of stuff isn’t going to intimidate us from running pieces that are critical of the EU, which is a structurally neoliberal institution that polices its borders through a deliberate policy of drowning Africans and Arabs”.

And, he wrote that:

… as regards Britain, the facts are EU rules impede Corbyn’s program: you can’t properly nationalise if you can’t abolish internal markets, you can’t build public industry with its state aid rules, you can’t renationalise the NHS with its public procurement rules, etc, etc

And, acknowledging that there is a “debate to be had about whether the anti-democratic nature of transnational institutions can be countered through the democracy we’ve won at a nation state level … we can’t have that debate if one side is determined to shut it down with pileons & hyperbolic bluster”.

A solid statement of editoral integrity.

Pity the Tweet Stalking Squad (TSS) doesn’t take the same lead.

As Thomas and I have individually and together stressed from the outset – Brexit might turn out to be a total disaster for Britain if the Right stay in government and harden their neoliberal austerity bias.

The way the current Tory government is proceeding demonstrates an incompetence that could end anywhere.

And if leaving the European Union provides a dynamic to renew and strengthen what is at present a fractured Right polity, then we would be the first to say it will end badly.

But what we have consistently argued is that there is a massive opportunity created by Brexit for British Labour to articulate a restated progressive voice by rejecting its neoliberal Blairite past.

I personally retain that position. Even if the Tories mess it up, a general election will come along soon enough and the Labour government will then have full sovereignty without the need to ‘obey’ EU law to move Britain ahead as an independent, progressive nation.

They should have confidence in that.

I followed up with a blog post – The Europhile Left use Jacobin response to strengthen our Brexit case (May 22, 2018) – to respond to a plethora of criticisms of our position.

The original Jacobin article was focused on assessing the state of play at the point in time given the ridiculous forecasts that were published by various agencies and economists around the time of the Referendum, which were deliberately designed to subvert the Leave vote.

We noted that, at that point, far from the deep recession that the British people were told would ensue, quite the opposite appeared to be occurring.

Real GDP growth continued.

Unemployment continued to fall.

Participation rates rose.

What particularly enraged our critics, and appears to be still enraging the more daft members of that group, was this part of the article:

Particularly embarrassing for the professional doomsayers is the data on British industry over the past two years. Despite the uncertainty concerning the negotiations with the EU “manufacturing is seeing its strongest growth since the late 1990s,” according to the Economist as well as the British manufacturers’ association EEF. This is largely due to a growing demand for British exports, which are reaping the benefits of the lower pound and improved world trade conditions. According to a report by Heathrow Airport and the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR), UK exports are at their strongest position since 2000. As the Economist recently put it: “Britain’s long-suffering makers are enjoying a once-in-a-generation boom,” as the shifts induced by Brexit engender a much-needed “rebalancing” from boom-and-bust financial services towards manufacturing. This is also spurring a growth in investment. Total investment spending in the UK – which includes both public and private investment – was the highest of any G7 country during 2017: 4 percent compared to the previous year.

It is important to note that the article in question was written before the first-quarter 2018 National Accounts data was published by the British ONS.

So, like the rest of the article, it was a statment at a point in time using what data was available and drawing on assessments from other information sources such as the EEF.

The reference to the term “boom” appears to still rankle the critics.

They should just get over it.

We did not refer to the state of play at the time as a “boom”. We just quoted the Economist Magazine’s own assessment. But the data at the time certainly wasn’t indicating a meltdown.

Importantly, we did not provide any forecasts of the period ahead in this regard. We were not making any long-term predictions.

However, like a stuck record, those august attention-seeking Twitter heroes, one of which Tweeted he was embarassed because his surname had the same first two letters of my surname (pettiness, it seems has no limits), still claim that our article lied with respect to that statement above about manufacturing, exports and total investment.

The latest national accounts was thrust into Twitter at the weekend allegedly proving that we were liars.

As the graph on Manufacturing above showed, in the March- and June-quarters of this year, Manufacturing output contracted.

That reality in no way refutes what we wrote in the Jacobin article, which was based on 2017 data that remains as it was when we wrote the article (no revisions).

As I noted, to say otherwise is equivalent to the logic that the GFC never happened because economies grew again!

These Twitter heroes claim they are just ‘fact checking’ and because we are liars we should withdraw the article and presumably, disappear down some dark hole.

The demand for an apology came from a person who claims I am “unpleasant because I am unpleasant”. Go figure that logic and pettiness.

Anyway, what the current national accounts data has to say is irrelevant to the credibility of our Jacobin article, unless, of course, it dramatically revised what was going on in 2017, which it didn’t. So irrelevant!

We wrote nothing in that article about what the case might be in the quarters after our article was finalised.

And we drew on assessments by external bodies – The Economist magazine (which is anti-Brexit and conservative to boot) and the British manufacturers’ association.

Yes, the latter may have a self-interest in talking the data up but the data, itself, around that time was pretty good.

Some facts.

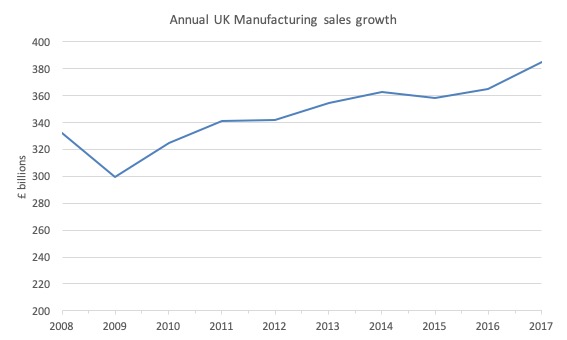

The British ONS publised their – UK manufacturers’ sales by product: 2017 – on July 3, 2018, which brought together previous data releases that we consulted when we wrote the Jacobin article.

Figure 1 is interesting – it shows the Total value of UK manufacturers’ product sales from 2008 to 2017.

Here it is. Following the Referendum in June 2016 there was a strong growth in Manufacturing sales. The previous period from 2014 to 2016 has been marked by flat sales.

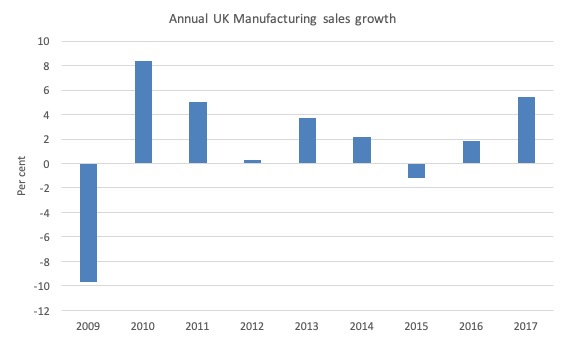

Between 2016 and 2017, total sales grew by £19.8 billion or 5.43 per cent (see next graph).UK_

The average growth of British manufacturing sales in the period 2008 to 2016 was just 1.31 per cent.

So a 5.43 per cent growth in sales in 2017 – after the Referendum vote in June 2016 was exceptional.

Whether one calls it a boom or not is rather moot. We reported the terminology of other on-lookers as above. But the data in that period was impressive.

We didn’t misrepresent it. Nor what happened after that undermines the analysis and conclusions we drew at that point in time.

The current data tells us, if anything, that the two-quarter slump in Manufacturing output is over, given the 0.6 per cent increase in the September-quarter 2018.

But I would not draw any firm conclusions based on one-quarter of data.

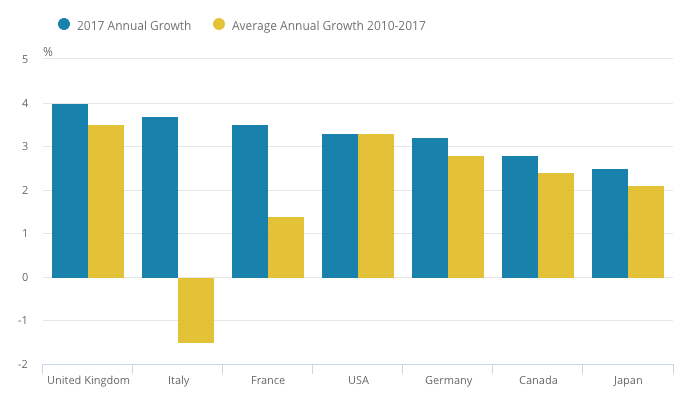

What about total investment spending in the UK in 2017 and its relativity to the G7 nations?

Note we wrote a very simple statement:

Total investment spending in the UK – which includes both public and private investment – was the highest of any G7 country during 2017: 4 percent compared to the previous year.

So we were simply saying that between 2016 and 2017, the UK had the highest growth in that component of expenditure among the G7 nations.

We were not making judgements on the level (high or low, adequate or inadequate) and the statement holds true irrespective of the base from which that growth ensued (low or high).

As I noted in the previous response – – The Europhile Left use Jacobin response to strengthen our Brexit case (May 22, 2018) – the investment performance in Britain was from a low base.

The UK endured a policy-driven recession for many quarters which derailed capital formation.

Further, our article was talking about investment growth not investment as a proportion of GDP. They are two different things altogether and it is irrelevant to the point we were making about the growth of British investment post-Referendum.

Moreover, in the Jacobin article, we linked to a Financial Times report (March 29, 2018) – UK investment spending leaves G7 rivals trailing – to provide an easy to access evidence trail.

That article was summarising the latest ONS data on British investment:

Annual growth in investment spending in the UK was the highest of any G7 country during 2017, according to figures published by the Office for National Statistics on Friday …

The figures suggest that uncertainty over the outcome of the Brexit negotiations has not chilled overall investment spending in the UK.

So the Financial Times was just reporting from the ONS. I went back to the original source today to see if anything had changed by way of revisions to the data for that particular data publication.

The specific Office of National Statistics release (March 30, 2018) – Business investment in the UK, revised: October to December 2017 – provided some “International comparisons of GFCF” as part of that release.

The ONS concluded:

Between 2016 and 2017, the UK had the strongest growth in gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) of any G7 nation at 4.0%

We didn’t misrepresent the data in any way.

We reported it almost exactly as the ONS had published it.

Conclusion

There were no factual errors in the Jacobin article.

Certainly, things change and some of the factual conclusions that were drawn at the time of writing have been overtaken by new data.

We have also never suggested that Britain is in a good shape at present. Indeed, my on-going analysis of the Britain economic situation could never be construed as being supportive of current economic policy, the overall performance of the British government nor a sign that there should be complacency on the side of the Left.

In the Jacobin article, Thomas and I wrote:

Just as Britain’s current economic woes have much more to do with domestic economic policies than with the outcome of the referendum, the country’s future largely depends on the domestic policies followed by future British governments, and not on the result of the UK’s negotiations with the EU.

And I followed that sentiment up with this type of analysis – How to distort the Brexit debate – exclude significant factors! (June 25, 2018).

But none of the ‘new’ data revises the old. What we said then remains true.

And while the on-going Brexit saga has somewhat altered things – some for the good and some for the bad – I would not (and I am sure this also applies to Thomas) change the tenor of our April 2018 Jacobin article.

The latest events in Italy only serve to reinforce our view that the EU is a neoliberal, corportatist state and Britain should be so lucky to escape it.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hello,

Great article.

Showing the sectoral balances would be a great addition.

Certainly, the conclusions reached in the Jacobin article are supported by the sectoral balances.

The private sector balance in the UK is about minus five (-5% of GDP) last time I calculated it. That is one of the worst in the world and the worst in the developed world.

But for private credit creation at about 3.5% of GDP, UK aggregate demand would have collapsed into recession long ago and soon will when credit creation collapses. The UK is the same situation as the USA in the late 1990s operating under the Clinton surpluses and powered on by private credit creation until that too faded away.

I’m no expert economist, so I may be wrong.

Business investment is a good thing. It means that business sees growth in the future, either in the local market or the export market.

OTOH, business inventory growth is a bad thing. It means that businesses were wrong 3 months ago about what the future would be like in 3 months (i.e. now). Or at least if the report were current and not really 4 months old.

IIRC, these 2 numbers are added together in most economic reporting. As an indicator of future changes inventories should be deducted from investment, not adder to it.

Leaving the EU or staying in the EU is an issue in its own right and deserves to be discussed as such.

The side-effects for party politics and ‘left’ versus ‘right’ are just that – side effects. Using the EU referendum as a proxy for the utterly boring war between factions is what has been divisive and intractable. It will never end until people have clear heads on what the EU actually is.

Meanwhile, the EU has for decades ramped up this war between party political factions precisely so that it can achieve its goals.

That is what you see before you now: the endless bickering over secondary and tertiary issues, hiding the primary one: what the EU is and what being in it or leaving it means for your system of government, and democracy.

The economics and the party political power politics are separate issues.

Reducing everything in life to economics or party political ‘left’ v ‘right’ right wars is part of the problem. It’s a big part of why supposedly civilised people are behaving increasingly nastily towards each other.

From ‘Why the Left Should Embrace Brexit’

“… the notion that the British people are incapable of defending their rights in the absence of some form of “external constraint” is patronizing and reactionary.”

Hear hear.

There are, sadly, a lot of people who want to treat the electorate like children, and take away their democracy ‘toys’, like Plato’s Guardians.

What worries me is that the Tories will spin growth and apparently low unemployment as a sign that austerity ‘worked.’

In the recent budget, which was in fact a homeopathically quantifiable climedown from austerity was painted as ‘the reward for the great sacrifice of the British people.’ The Tories will use sustained growht as more retrospective justification for hammering the poor, sanctioning the unemployed and houdning the ill.

FYI: vacancies are at a record level, just like employment and employment and unemployment rates (record low). Somewhat surprising, indeed. But for the records: it shows that ‘trust’ in a specific government might be overrated as a factor influencing the economy.

Overall gross investment might be up – but this is due to government investment. Business investment is weak and of concern (depending on its composition).

@Alan Longbon

Dear Alan,

Liked your response. I know you are collecting data for sectoral balances world wide. In the UK case we know they have been running governmental deficits a along since WW2 more or less. Also current account balances are negative since the 70s. Do you say that government deficits are not big enough when private sector balance is this negative(for how long?). Or are corporations(and households) overinvesting? I thought business-investing in the west incl the UK generally is to weak(long term)! Netexports are today almost zero(not in the usual deficit). So is the credit-binge running abroad or is giving ground for domestic GDP?

My post above 19:51

Of cource the discourse is about the shrinking deficit from 10% 2010 to 2% 2017, aka the austerity-debate.