In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

British productivity slump – all down to George Osborne’s austerity obsession

Apparently, whenever some poor economic news is published about the United Kingdom, journalists have to weave in their on-going gripe about the outpouring of democracy in June last year that saw the Brexit vote to leave successful. Its hysterical really. The most recent example is from the otherwise sensible Aditya Chakrabortty from the UK Guardian (October 17, 2017) – Who’s to blame for Brexit’s fantasy politics? The experts, of course. The story has nothing much to do with the June 2016 Referendum but more about massive forecasting failures of the Office of Budget Responsibility. But somehow the story opines about the lies told about Brexit and a fiscal “bloodbath” – the latter being the description for the fact that the fiscal deficit is likely to increase a little as a result of a slower than expected economic growth outcome. The UK Guardian continually writes about these two obsessions – the first that Brexit will be a disaster and the second that the fiscal position of the British government is in jeopardy and will undermine the capacity of the government to defend the economy if a major downturn comes along (as a result of the ‘Brexit disaster’). The narratives are interlinked – Brexit is bad, it will cause deficits to rise which are bad, and the government will be powerless as a result of the rising deficits to stop the bad consequences of Brexit – which is a big bad. All propositions are largely nonsense. Brexit will be bad if the British government continues to implement neoliberal policy. Rising deficits do not alter the spending capacity of government. And as a currency-issuing government, Britain can always arrest a recession, if there is political will. The fact is that the OBR forecast errors are just part of the neoliberal lie. And the productivity growth slump the OBR has now ‘discovered’ predates the Brexit referendum by years and is all down to the misplaced austerity imposed by George Osborne in June 2010. But it is disappointing to read this sort of stuff being repeated by so-called progressive commentator. There is clearly more work to be done via education.

The UK Guardian article (October 17, 2017) – Who’s to blame for Brexit’s fantasy politics? The experts, of course – Aditya Chakrabortty focuses on the latest – Forecast evaluation report – October 2017 – (FER) issued last week (October 10, 2017) by the British Office of Budget Responsibility.

This is an annual report, “published each autumn, examines how our forecasts compare to subsequent outturn data and identifies lessons for future forecasts”.

The OBR Press Release (October 10, 2017) – Deficit falls, but productivity growth disappoints again – discloses that:

1. “Real GDP growth in the period up to mid-2017 was weaker than predicted in both our March 2015 and March 2016 forecasts, but nominal GDP growth – which is the more important driver of the public finances – fell short of our March 2015 forecast by a smaller margin while it actually exceeded our March 2016 forecast”.

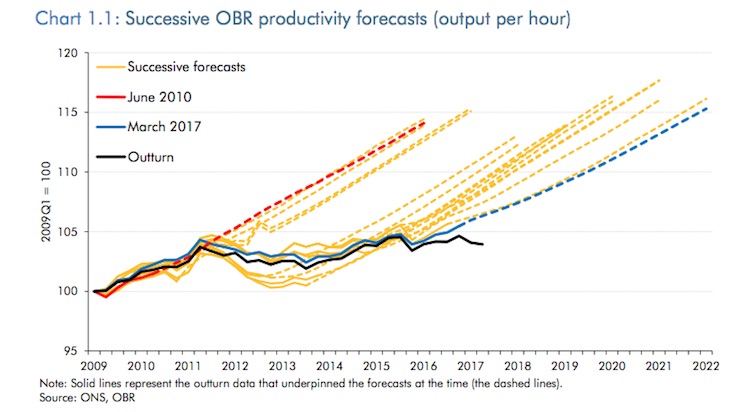

2. “One recurring theme in past reports has been productivity falling short of our forecasts (Chart 1.1) while employment and average hours worked have exceeded them.”

The following graph reproduced from the OBR October FER shows the sequence of productivity forecasts from the OBR starting with the estimates from the FER October 2010 through to March 2017 together with the actual productivity performance (black line).

They clearly were desperate to hang on to belief that the return to the pre-2011 trend would come anytime soon – except it didn’t and so ‘anytime soon’ kept getting pushed out.

Even in March 2017, just 6 months or so ago, they were making the same mistake.

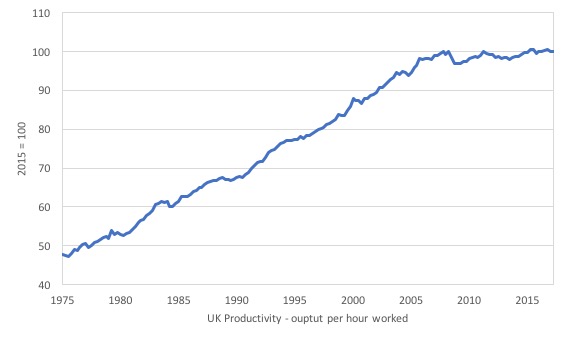

Here is a longer time series – from the first-quarter 1975 to the June-quarter 2017 – for output per hour worked. The same sort of pattern emerges if we use the output per person employed measure.

The cyclical swings throughout this extended period are evident and the size of the GFC downturn is highlighted within the red-rectangle.

The point is that something connected with the GFC has led British labour productivity to flatten out. And the cause of the productivity slump is not related to the Brexit referendum, despite what the ‘Remain Cheer Squad’ would have you believe.

Structural explanations of this slump are also unlikely to have traction. The massive cyclical contraction pushed British productivity growth of its past trend. Structural factors work more slowly and we would not witness such a fall if they were implicated.

OBR has clearly made a series of major forecasting errors in terms of how quickly the economy was growing.

It is now clear that:

Actual productivity growth averaged 2.1 per cent a year in the pre- crisis period, but has averaged just 0.2 per cent over the past five years.

Even in March 2017, OBR forecast productivity growth to read 1.8 per cent by 2021, but now admit that they will be “reducing our assumption for potential productivity growth over the next five years”.

The two elements to their forecasting mistakes are:

1. Real GDP growth was well below OBR estimates. This shortfall has been dominated by “the weakness in business investment”, which I will consider soon.

2. Employment growth has been “stronger-than-expected” and “hours worked” have grown more than OBR thought – by some margin.

GDP is the numerator and some measure of employment (hours or persons) forms the denominator of the productivity measures. So, taken together, productivity growth turns out to be well below what they forecast.

So OBR misread all elements.

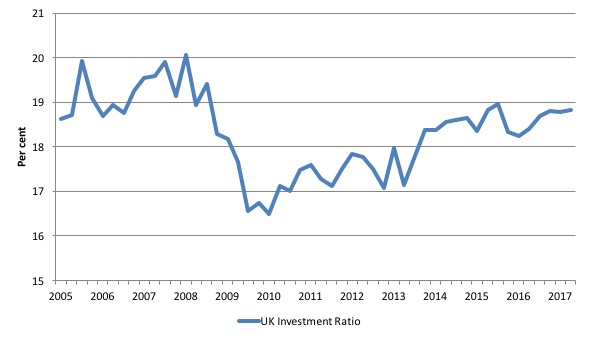

The next graph shows the UK investment ratio (total capital formation as a percent of GDP) from the March-quarter 2005 to the June-quarter 2017.

The drop associated with the GFC is quite stunning. It went from 20.1 per cent of GDP in the December-quarter 2007 to 16.5 per cent by the December-quarter 2009.

That is a huge cyclical swing and tells us how deep the GFC recession was in the UK. Real GDP growth was negative for 5 successive quarters starting in the June-quarter 2008. The British economy shrunk by 6 percentage points between the March-quarter 2008 to the September-quarter 2009.

Why would that cause productivity growth to slump then fail to recover?

A major driver of productivity is investment – both public and private.

While business investment is cost sensitive (so may respond to interest rate changes), mainstream economists usually ignore the fact that expectations of earnings are also important as are asymmetries across the cycle.

Cyclical asymmetries mean (in this context) that investment spending drops quickly when economic activity declines and typically takes a longer period to recover. So fast drop and slow recovery.

The cyclical asymmetries in investment spending arise because investment in new capital stock usually requires firms to make large irreversible capital outlays.

Capital is not a piece of putty (as it is depicted in the mainstream economics textbooks that the students use in universities) that can be remoulded in whatever configuration that might be appropriate (that is, different types of machines and equipment).

Once the firm has made a large-scale investment in a new technology they will be stuck with it for some period.

In an environment of endemic uncertainty, firms become cautious in times of pessimism and employ broad safety margins when deciding how much investment they will spend.

Accordingly, they form expectations of future profitability by considering the current capacity utilisation rate against their normal usage.

They will only invest when capacity utilisation, exceeds its normal level. So investment varies with capacity utilisation within bounds and therefore productive capacity grows at rate which is bounded from below and above.

The asymmetric investment behaviour thus generates asymmetries in capacity growth because productive capacity only grows when there is a shortage of capacity.

This insight has major implications for the way in which economies recover and the necessity for strong fiscal support when a deep recession is encountered.

These dynamics are covered in my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned.

In some of my earlier work (with Joan Muysken) – for example, here is a working paper you can get for free (subsequently published in the literature) – we developed a model based on the notion that investors facing endemic uncertainty make large irreversible capital outlays, which leads them to be cautious in times of pessimism and to use broad safety margins.

The problem of asymmetry can be attenuated if government steps in during a downturn and arrests the spending collapse. Appropriate fiscal stimulus initiatives can thus shorten any non-government spending declines and limit the investment slump.

This not only shortens the decline into the activity trough but also means that potential output growth can be maintained at previous rates.

The opposite is of course also the case.

Imposing pro-cyclical fiscal austerity of the scale that George Osborne initiated when the Tories came took government in May 2010 is the last thing a government should do when non-government spending is in retreat.

Fiscal austerity in these circumstances exacerbates the typical asymmetry associated with investment expenditure and is a major reason why business investment in the UK has been so weak.

We often focus on the short-term negative impacts of fiscal austerity, but in this case, it also has serious long-term impacts on both the rate of business investment and the potential growth rate (which falls as capital formation stalls).

The longer it takes for business investment to recover, the worse will be the long-term impact on potential GDP growth. In turn, this means that the inflation biases are increased because full capacity is reached sooner in a recovery – often before all the idle labour is absorbed.

So, while George Osborne is long gone, the negative impacts of his policy folly will reverberate for a long time to come. His failings will continue on for many years and the flat productivity growth is one manifestation of that failing.

The media focus seems to have ignored this issue and instead is emphasising the impact on the fiscal balance.

The UK Guardian article (October 10, 2017) – UK productivity estimates must be ‘significantly’ lowered, admits OBR – focuses on this issue.

They write that the productivity “downgrade”:

… will wipe out about two-thirds of the government’s £26bn budget surplus from 2017 to 2021. The stockpile, seen as a war chest for a potential slowdown after a disorderly and harmful EU exit, was set aside by the chancellor in the previous budget in March.

Hammond is under pressure to increase spending, despite weaker economic readings.

Phew!

That little piece of prose is riddled with neoliberal myths.

1. A fiscal surplus does not constitute a “stockpile” or a “war chest” that can help the government spend more later.

2. What logic is there in the statement that “Hammond is under pressure to increase spending, despite weaker economic readings”? The responsible position is exactly the opposite – Hammond should increase spending because of the weaker economic readings.

Even the likes of Aditya Chakrabortty is pushing the line that the fiscal position is in jeopardy as a result of the poor productivity growth.

In the article cited in the Introduction, he writes in relation to OBR’s revisions:

Now it has had to admit reality – and that will mean our forecast growth rates now halving and the public finances heading for what officials term a “bloodbath”. In other words, if Hammond sticks to his austerity plan, you can expect the cuts to our disability benefits, schools and hospitals to drag on for even longer.

Why would a so-called progressive journalist use the language of the “officials” – to wit, “bloodbath” when describing the cyclical impacts on the tax take by government.

So what if the fiscal deficit rises? Is that a “bloodbath”? Clearly not.

It is highly likely that as the economy slows the fiscal position of the British government will move towards a higher deficit as the tax components tied to non-government economic activity yield lower flows and government welfare payments rise.

That doesn’t reduce the capacity of the government to spend. In fact, as noted above, it tells the government it should increase discretionary expenditure to get the economy going again.

Whether the Chancellor Hammond gets that is another question. But progressives should not be buying into the idea that a rising deficit is a “bloodbath” or that fiscal surpluses somehow provide the government with more spending capacity in the future.

The productivity slump is down to the fact that that both sides of British politics have failed to articulate a growth strategy where the public sector creates and supports an environment where non-government investment expectations are optimistic and households can save more given their precarious debt situation.

The whole growth strategy since 2010 has relied on ever-increasing private debt as government try to achieve fiscal surpluses. Exactly the opposite to what is required.

Conclusion

Whether Brexit turns out to be a bad thing for the UK will not be the result of severing ties with the corrupt and dysfunctional European Union. It will all be down to the policy positions that the British government takes.

If it persists with its neoliberal obsession of pursuing fiscal surpluses, then the outcomes are likely to be bad. If not, otherwise.

For British Labour, the choice is the same. Continue to rave on about fiscal rules (as if they define responsible policy) or grow up and recognise the intrinsic capacities its had as the currency-issuer to create strong employment growth and first-class public infrastructure – both of which crowd in private investment.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“The whole growth strategy since 2010 has relied on ever-increasing private debt as government try to achieve fiscal surpluses. ”

And ever increasing use of subsidised cheap imported labour to prop up out of date capital. Why invest when de-unionised labour is cheap and available? And those firms that want to invest can’t because their profit margins are being eroded by the cheap labour parasites.

What little top line GDP growth there has been, has been down to more hours worked by new people. GDP per capita, unsurprisingly, is about the same shape as the productivity curve and the private debt curve.

Neil,

There are a number of factors which, when identified and added together, will provide a convincing explanation of why productivity levels have continued an slide in the UK.

A useful assessment would be aided, for example, by comparing what is happening in this country with other European nations – taking account also of the various influences that the introduction of the EU has provided; including even pre EU investment trends, for example.

Also the impact here, and EU, of trends in global manufacturing investment over the last couple of decades are a matter for concern. This historic perspective ignites a debate over what the role of a JG would have accomplished during that volatile period in the 1960’s and 70’s when existing UK nationalized industries where undergoing increasing pressure to make dramatic workplace (productivity) changes.

I can remember some very local instances of great union resistance to these changes, any temporary outcomes amounted merely to the creation of buffer jobs rather than part of a progressive shift to a greater productive economy.

And, taking up your point about cheap labour. From my vantage point, I see “foreign” workers doing jobs and trades that were never previously occupied by natives. looking into the future, we also have to consider the strong possibility that the whole concept of work (and human activity) is about to undergo a historic transformation.

“A useful assessment would be aided, for example, by comparing what is happening in this country with other European nation”

An even more useful assessment is aided by comparing what is happening in the UK with what is happening in Japan – an actual island nation where they have invested in automation and using elderly workers effectively.

They continue to bumble along with a similar improvement in GDP per capita despite a shrinking population and, amazingly, net zero migration.

“From my vantage point, I see “foreign” workers doing jobs and trades that were never previously occupied by natives. ”

I’m sure you do, but the question is why is it ok to rip them away from their home and family to transport them here? Are you suddenly a fan of Norman Tebbit’s ‘on your bike’ line? ISTR most people on the left hated that concept in the 1980s, but apparently it is now a fantastic idea as long as you are brain draining the investment of another country in the process.

Why not move the trade to where they are. That is the fundamental change we are proposing here – that capital is forced to go where the labour is, not forcing people to wander the continent and the world looking for their next gig. There’s no freedom in that.

If a firm here isn’t employing the ‘natives’, then that is because the wage and conditions of the job are insufficient inducement or it is in the wrong place. So they either have to automate, go bust, or move elsewhere to where the labour is. None of which is a problem when you have a Job Guarantee and a floating rate currency.

Bill, what red rectangle?

The OBR has been consistently disappointed by the failure of the real economy to conform to its wishful thinking.

I am forced into wishful thinking by the OBR’s masters.

Wishful thinking is a tactic ,not a strategy.

As positively as I persevere,the OBR might one day realise, it doesn’t actually work.

There are a few reasons why firms import labour and none of them are to do with filling a skills gap. The first is that imported labour is easier to control. When a worker is under threat of deportation if they join a union or stand up for their rights, then the control is much easier. For those that study their Marx and Engels another more sinister reason is to increase the size of the reserve army of labour. This then has the effect of disciplining all workers and not just those that are imported. Once a reserve army of labour was a domestic issue. Now it has, via trade agreement etc been internationalised so now we have the international brigade of the RAL

Neil, your final para on employing the natives needs I think to be slightly modified. Let me take the harvesting of asparagus. It is in the right place and it is not possible to move elsewhere.

A number of growers have found that foreign workers are for some reason superior to British workers with respect to asparagus harvesting. Since the pay by some is the minimum wage, they do not know why the British who turn up for this work either won’t or can’t do it, but they have found that they have to let them go. Or they leave. The skill consists in deciding which asparagus plant to cut, how to cut it, and when to cut it. What some growers have discovered is that British workers appear to be either unable or unwilling to learn this set of skills.

We have to note that there are such cases. But I would argue, as I am certain you would, that it is invalid to go from this to a generalization to the effect that British workers are lazy or inept tout court and that this is why foreign workers have to be hired. The same considerations apply to so-called benefit cheats. The government knows, on average, how many there are, and there are not many. The number is minuscule. That they exist is no justification for Draconian welfare rules. But such has been the justification.

Let me take a different kind of case: accountancy. If we find that British workers are innumerate and can’t master accounting skills, we can’t blame those job seekers. We have to look at the education system which these job seekers were exposed to. We would discover it was inadequate in respect of the dissemination of these particular skills, for a large number of reasons, some of them having to do with the dominant cultural landscape. Accountancy better fits your principles, I think.

Bill, Larry Elliott in the Guardian on Tuesday discussed the BoE’s and Mark Carney’s ‘concern’ about inflation. Concentrating on whether the inflation figure was within 1% of their 2% target, but seemingly not concerned about how a rate rise would affect those whose wages have stagnated, though they are aware of this. So fixated are they on their numerology, this is effectively ignored. The less well off will be hit the hardest. But since they don’t contribute much to GDP or its growth, that is all right then.

Hammond has claimed earlier that he doesn’t know any economics but that he is learning. From the Treasury, whose mind set hasn’t left the 1920s. Hammond may be able to manipulate a spreadsheet, but it doesn’t follow from this that he can interpret it appropriately.

Larry,

An acre of asparagus can yield enough profit for one owner per anum, but it can only provide work for 1-2 months.

It can only benefit those workers who can arbitrage their labour for those months.

Indigenous labour has no real upside

Larry

You do touch on a point, that there is no such thing as unskilled labour.

Neil,

“So they either have to automate, go bust, or move elsewhere to where the labour is. None of which is a problem when you have a Job Guarantee and a floating rate currency.”

What has intrigued me about that statement, and other variations on the same theme, is the apparent assumption that any initial fall in living standards (created by lower productivity/job losses) will be retrieved as a follow on from a JG and floating currency.

It may be that a full explanation of this phenomena is contained in Bill’s extensive chronicles. If you would direct me to it I would be grateful, for I believe the ordinary man/woman in the street would learn to appreciate the initials MMT purely on a positive example of its successful pathway.

Interesting as always. Could I ask a basic question on a related MMT principle please? I don’t seem to have found an answer from reading around on the subject, or perhaps I just haven’t understood it:

I understand the position that sustained deficits are nothing to be feared, but also the position that inflation would result from a scenario in which there were ever expanding interest payments on government debt. But what I don’t understand is what stops the first from necessarily turning into the second? One idea I had was that perhaps taxes on the recipients of interest payments could rise to stop the deficit always increasing, another is limiting the deficit to a level which maintains the debt/GDP ratio from increasing in the longer term, but I don’t seem to have come across a definitive explanation. Any thoughts welcome! Thanks.

“What some growers have discovered is that British workers appear to be either unable or unwilling to learn this set of skills.”

If the asparagus grower was required to build, on their growing land, the required houses, the required schools, the required hospitals and extra food, plus staff them out with the required service staff and house and feed them, do you think they would still be growing asparagus.

Or would they then grow carrots and use a machine to harvest?

The idea that British workers will not harvest asparagus, when they have done for generations previously, is a complete myth. What they won’t do is break their backs for no money (quite literally. Asparagus picking damages people’s backs). In other words the people who would otherwise pick the crop are using their dexterity in higher productivity jobs at better wages with less back ache. The Germans found the same thing for the same crop with German workers in 1998 – back when Germans needed visas to bring in Poles.

Asparagus is a low productivity crop destined for wealthy tables. It grows just fine elsewhere. The profit comes from the low wages on offer, the health damaging conditions for harvesting and crowding out the local facilities. Privatising profit and socialising losses in other words.

So I disagree with your assessment – largely because the premise is wrong. Asparagus grows fine elsewhere, and the “We can’t get the skills” line comes from the very people who don’t want to pay the wages required.

“but also the position that inflation would result from a scenario in which there were ever expanding interest payments on government debt.”

(i) don’t pay interest on government debt. There is no need to do so.

(ii) Inflation won’t necessarily come from interest payments. It depends whether those interest payments are saved or spent. If the Bonds are owned by the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth fund they will be saved.

(iii) if you do get inflation, and you think the interest payments are causing it, and you think paying interest to rich people is something you should do, then you need to stop somebody else spending to make room for those payments.

The MMT lens shows that bond interest payments are just a marketable, transferable welfare cheque to the wealthy. The only legitimate use for them is to back private pensions in payment. At which point you have to ask if the private pensions are private at all.

“is the apparent assumption that any initial fall in living standards (created by lower productivity/job losses)”

You get higher productivity when you have job losses as the output is picked up by the expansion of firms with superior methods, plus the public goods created on the Job Guarantee.

For example, there is a street in my town where 19 people currently wash cars. One guy in a machine who sits there most hours quite lonely, and 9 other people in two sets of hand car washes. The price is the same. All of the people are currently subsidised with public ‘Tax Credits’ to make up their wages.

Under a Job Guarantee 17 of those people would be repairing the endless pot holes in the roads on the Job Guarantee (or some other nice to have public provision), and 2 of them would wash all the cars with the machine. 17 of the people receive a public wage, and 2 receive a full private one with no subsidy. Less land is used for the process, and the machine makers make more profit – encouraging development of better machines.

That’s clearly a more productive arrangement.

@Neil Wilson,

But the machine can’t clean the inside of the car (yet!), which is always the most tedious bit to do yourself. For me, that’s the only reason to go to a car wash at all. The rain takes care of the outside : )

Fruit and vegetable picking has long been associated with exploitation and poor conditions. marx talks about this extensively in Volume 1 of Capital.

Neil makes the point well that ‘What they won’t do is break their backs for no money.’ This is why the Tories instituted ‘welfare reform’ imitating the German Harz Reforms of the previous decade. They knew it wasn’t worth working with atrocious housing costs and crippling private debt beyond that, so they had to force the issue by saying ‘if you won’t play our game we’ll leave you with nothing.’ This was accompanied by language framing around benefit claimants and the whole ‘lazy’ meme.

You don’t work well when you are demoralized, feeling as if your efforts are futile and there is no perceivable positive outcome. The Tories used the ‘gun-point’ appraoch which was largely introduced by Blair’s Labour as they instituted endless reassessment of ill people and started to treat benefit claimants like criminals-research shows that marginalisation of the ill and unemployed gathered pace under Brown/Blair.

Neil, you have misrepresented my position. It is, as I am certain you are aware, that the construction of such infrastructure by the grower is unrealistic. Indeed, it appears to be a tenant worker arrangement. And the cases I had in mind did not have workers working for no money — they were not being cheated. This misrepresents my position entirely. Of course, people are quite right to refuse to be exploited if they can.

Many growers grow one crop for a period of time and then switch to another in a rotation of crops scenario. And the addition of a machine is not possible in this particular scenario, which is one reason I picked it. I also selected it because it required a particular set of specific skills that a machine could not at this time carry out. A machine is not a general solution currently. It is not a good idea to overgeneralize.

What has happened in previous generations does not necessarily apply to the current one without modification. Why a change might have taken place either psychologically or culturally would have to be argued case by case. I doubt there is a general rule.

Paul, I never said that there was such a thing as completely unskilled labor. But there are some skills difficult to acquire, like that of steel master, the position held by the individual(s) responsible for deciding when to pour the liquid steel in a steel mill. This skill, which was reckoned to take around 10 years to master, was not acquirable for some, even though an apprenticeship was open to most steelworkers. It is true that most jobs in a steel mill were not of this kind.

My father found tensor calculus to be completely trivial, but said that many of his classmates had great difficulty understanding it. These same people, however, engineers all, along with fellow students, put the provost’s VW Beetle in the top of a tree. No one in the city administration understood how they had been able to do this — they had to get a crane to get it down. The university president bragged about it, saying it showed how bright his students were. I can’t see a university president reacting in that way today.

I am arguing only that skills are unequally distributed within the population.

Paul, regretfully, part of my comment got garbled. I intended to say that what you had said I said was indeed what I had said. My first sentence is a complete mish-mash. I merely wished to reinforce and clarify what I had said. Maybe I have made the situation worse. Sorry about any confusion.

“And the addition of a machine is not possible in this particular scenario”

It is Larry. You don’t grow asparagus for rich people, you grow carrots for poor people. Those are harvested by machine.

The presumption is that the capitalist is correct in their choice of output.

Great blog.

Mindless austerity aside since 2010; The UK

has had long term lower productivity compared to the

Rest of europe.the likes of Italy and France far outmatch UK productivity levels.

This was the case before Osbourne’s cluelessness

Firms reluctant to invest in productivity .

Intelligent industrial policy should address this.

@neil,quite agree gdp per capita should be the focus not gdo growth.I’ve rrad some great articles on japan decreasing population and GDP correlating with increasing gdp per capita-which surely should be the entite focus of public policy.

“I am arguing only that skills are unequally distributed within the population.”

That is correct of course. Teachers and healthcare workers being the main categories of concern. Which is why throwing money at an area under pressure won’t really help matters.

Can’t believe how many people at the top still believe that the government is a household.

Even mainstream economics teaches that it is not no?

Tom. the UK Chancellor, or more specifically the UK treasury, has stated that it is putting money aside for a hard brexit. Frightening really.

In answer to my own question on economic recovery, how about Bill’s reference to Argentina’s experience – in blog May 21st 2013 “Argentina and Greece – credible analogy or not?” as an example.

@Neil “Teachers and healthcare workers being the main categories of concern. Which is why throwing money at an area under pressure won’t really help matters.”

Money is a big factor in whether a trained physicist becomes a teacher or an investment banker. Surely you do you believe that despite the role of government in setting the teacher’s terms and conditions that the market is still efficient in the allocation of resource?

The market never has been has efficient as neo-liberal theory would promulgate, but efficient use of resources is not something that can be roundly claimed by socialist policies either, judging by historic evidence.

What socialism can claim is a more humanitarian approach to economic priorities, but even in this respect it falls short for various reasons, including degrees of corruption.

Bill argues with considerable conviction that markets create exploitation with the profit motive being the driving force. I would only qualify that opinion to the extent that for vast numbers of business owners the fear of failure is real; insolvency is usually associated with disaster of catastrophic proportions.

It is the combination of ambition and the drive to improve/innovate products that has brought the incredible progress of western economies since the industrial revolution.

We are not yet far enough down the road of well-being that poverty has been eradicated but the striving of capitalists should not be easily dismissed.

Even if global resources were more equitably distributed, there would still be the human desire to strive for advantage – even over our brethren; for this is an intrinsic human characteristic.

If productivity was not to differentiate us, then it would certainly be something else, like the pace at which resources are turned over, for example.

Strive for whatever version of economic ideology you believe in, for that is in essence a competition for superiority.

Bill,

Firstly, congratulations on your blog, it is always a very interesting read and a source of common sense on economics.

In your conclusions you wrote:

“Whether Brexit turns out to be a bad thing for the UK will not be the result of severing ties with the corrupt and dysfunctional European Union. It will all be down to the policy positions that the British government takes.”

Now, I have been following your writings about the EU for a number of years; most of it resonates with me; and they are a major reason why I have morphed from an EU-enthusiast into a EU-sceptic. For example, I find Greece has been treated extremely badly by its EU “friends”, and I agree with your assessment that the EU’s austerity policies undermine the prosperity of a large part of us Europeans. And yes, the EU has a very serious democratic deficit.

However, I do have the impression that, when it comes to the UK, the EU has been, on balance, more a source of good than of evil. I believe most prominent UK Eurosceptics don’t like the EU not because its rules and regulations prohibit the UK from adequately protecting its most vulnerable citizens, but because the EU forces them to protect them too much, thereby depriving them of the myriad character-building and prosperity-creating benefits of the unfettered free market. Similar things can be said about e.g. food-safety standards, I believe. Also, as the UK was not bound by the constraint of being in the Euro-zone, isn’t it equally true that the damage of the austerity policies inflicted upon the UK was to a large extent voluntary?

Given recent history, isn’t it highly likely that the policy positions that future British governments will take will be to the further detriment of the just-about-managing and the not-at-all-managing rather than the other way around? The recent success – or non-failure – of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour may prove the be the start of a shift in the right direction of political power and economic policies in the UK. However, if I were a UK citizen, I think I would regard Brexit more as a threat than an opportunity, despite my less-than-enthusiastic feelings towards the EU.

J.

J.

“if I were a UK citizen, I think I would regard Brexit more as a threat than an opportunity, despite my less-than-enthusiastic feelings towards the EU”. Unlike yourself, I am a UK citizen – and I could not disagree more. It seems inconceivable to me that anyone can believe that not going through with Brexit would represent more of a threat than an opportunity. The sooner Britain extricates itself from that disastrous, ill-conceived, wrong turning it ought never to have taken, the better IMO.

But Bill is surely right in his conclusion (which you quoted): if the opportunity which Brexit undoubtedly presents us with is squandered it will be through our own folly. It won’t be because the opportunity was never there. Is there anyone who doesn’t believe Greece would have been far better- off today if it had baled-out of the EZ when it was given the chance?

Robert,

Which opportunity does Brexit present that was not available to the UK inside the EU? Are there examples of cases where the UK wanted to increase the protection of its weakest citizens but could not because the EU prevented it from doing so? Are there examples of cases where the UK correctly realized it could use its currency-issuing capacity for the good of the people but was prevented from doing so by the EU? Maybe be there are, by I am not aware of any. For example, I read that there is a serious problem with funding the NHS. I am not aware of either Labour or the Conservatives making the case that, yes, we could just fund the NHS by printing more Sterling, but the EU prevents us from doing this. They all seem to agree that the fundamental problem is a lack of money on the part of the UK.

I don’t think you can compare the UK to Greece. The UK still has its own currency, Greece doesn’t. So yes, I am one of those who believe that Greece should have left the EZ, but the UK was never in the EZ, so it never needed to leave it. If the UK were in the EZ and leaving the EZ were one of the side-effects of Brexit then I would definitely agree that Brexit presents an opportunity to the UK.

To be honest, I really hope that the UK can make a success of Brexit, that the UK shows the rest of the EU that it can prosper on its own, that is does not have to relinquish its sovereignty and submit itself to EU “dictats” in return for easy single-market access, that it can relax the government’s budget and that the EU’s fixation on austerity is economic nonsense.

I have the feeling that most left-of-center Brexiteers hope that at some point a consensus will develop in the UK for economic policies that are far to the left of what the EU will currently allow, and that, in anticipation thereof, it is best to leave the EU here and now. Being a UK citizen you undoubtedly have a much better view on this than I do, but I have the impression that if the EU is constraining the UK from moving to the right rather than to the left.

J.

J.

We forfeited our sovereignty when we joined the EEC but we (a majority of us, to which I belonged) didn’t realise that that was what we were doing. de Gaulle’s case in support of France’s rejecting Britain’s application to join (disregarding his ulterior, machiavellian, motives) turned out to be prophetic. But of course the last person we couild accept such an argument from was de Gaulle. More fool us: we were living in a fool’s paradise.

The opportunities to which I’m referring are no more and no less than those attendant upon reclaiming our sovereignty. It doesn’t follow of course that we would necessarily have made the best possible use of it in the meantime had we never given it up – we shall never know now so there’s no point in debating it; what’s done is done (or not, as the case may be). All that matters now is what we do with it from now on.

J,

Bill has written about why the UK can be better off outside the EU than inside it, notwithstanding that, as you correctly point out, the UK does not have the fiscal constraints imposed on it by the currency union. For example, the EU has built into its treaties unwise neoliberal fiscal policy prescriptions, namely, limits on net spending. It also places limitations on the nationalization of industries. To be sure, these limitations have not had any meaningful relevance to the UK over the last several decades given the neoliberal nature of its governments. But the UK now has a Corbyn-led Labour government on the precipice of power, and the neoliberal elements of various EU treaties as applied by the ECJ could definitely constrain his government, against the public interest.

Robert, JT

We all seem to agree that up until now the EU has been a theoretical rather than a practical constraint on the UK using its sovereignty for the benefit of the poor and the needy.

I would also like to point out that afaik the UK has always been one of the countries pushing hardest for neoliberal rules and regulations at EU level.

J.