Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – October 13-14, 2018 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Assume that inflation is stable, there is excess productive capacity, and the central bank maintains its current monetary policy setting. In this situation, if government spending increases by $X dollars and private investment and exports are unchanged nominal income will continue growing until the sum of taxation revenue, import spending and household saving rises by more than $X dollars because of the multiplier.

The answer is False.

This question relates to the concept of a spending multiplier and the relationship between spending injections and spending leakages.

We have made the question easy by assuming that only government spending changes (exogenously) in period one and then remains unchanged after that.

Aggregate demand drives output which then generates incomes (via payments to the productive inputs). Accordingly, what is spent will generate income in that period which is available for use. The uses are further consumption; paying taxes and/or buying imports.

We consider imports as a separate category (even though they reflect consumption, investment and government spending decisions) because they constitute spending which does not recycle back into the production process. They are thus considered to be “leakages” from the expenditure system.

So if for every dollar produced and paid out as income, if the economy imports around 20 cents in the dollar, then only 80 cents is available within the system for spending in subsequent periods excluding taxation considerations.

However there are two other “leakages” which arise from domestic sources – saving and taxation. Take taxation first. When income is produced, the households end up with less than they are paid out in gross terms because the government levies a tax. So the income concept available for subsequent spending is called disposable income (Yd).

To keep it simple, imagine a proportional tax of 20 cents in the dollar is levied, so if $100 of income is generated, $20 goes to taxation and Yd is $80 (what is left). So taxation (T) is a “leakage” from the expenditure system in the same way as imports are.

Finally consider saving. Consumers make decisions to spend a proportion of their disposable income. The amount of each dollar they spent at the margin (that is, how much of every extra dollar to they consume) is called the marginal propensity to consume. If that is 0.80 then they spent 80 cents in every dollar of disposable income.

So if total disposable income is $80 (after taxation of 20 cents in the dollar is collected) then consumption (C) will be 0.80 times $80 which is $64 and saving will be the residual – $26. Saving (S) is also a “leakage” from the expenditure system.

It is easy to see that for every $100 produced, the income that is generated and distributed results in $64 in consumption and $36 in leakages which do not cycle back into spending.

For income to remain at $100 in the next period the $36 has to be made up by what economists call “injections” which in these sorts of models comprise the sum of investment (I), government spending (G) and exports (X). The injections are seen as coming from “outside” the output-income generating process (they are called exogenous or autonomous expenditure variables).

For GDP to be stable injections have to equal leakages (this can be converted into growth terms to the same effect). The national accounting statements that we have discussed previous such that the government deficit (surplus) equals $-for-$ the non-government surplus (deficit) and those that decompose the non-government sector in the external and private domestic sectors is derived from these relationships.

So imagine there is a certain level of income being produced – its value is immaterial. Imagine that the central bank sees no inflation risk and so interest rates are stable as are exchange rates (these simplifications are to to eliminate unnecessary complexity).

The question then is: what would happen if government increased spending by, say, $100? This is the terrain of the multiplier. If aggregate demand increases drive higher output and income increases then the question is by how much?

The spending multiplier is defined as the change in real income that results from a dollar change in exogenous aggregate demand (so one of G, I or X). We could complicate this by having autonomous consumption as well but the principle is not altered.

So the starting point is to define the consumption relationship. The most simple is a proportional relationship to disposable income (Yd). So we might write it as C = c*Yd – where little c is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) or the fraction of every dollar of disposable income consumed. We will use c = 0.8.

The * sign denotes multiplication. You can do this example in an spreadsheet if you like.

Our tax relationship is already defined above – so T = tY. The little t is the marginal tax rate which in this case is the proportional rate (assume it is 0.2). Note here taxes are taken out of total income (Y) which then defines disposable income.

So Yd = (1-t) times Y or Yd = (1-0.2)*Y = 0.8*Y

If imports (M) are 20 per cent of total income (Y) then the relationship is M = m*Y where little m is the marginal propensity to import or the economy will increase imports by 20 cents for every real GDP dollar produced.

If you understand all that then the explanation of the multiplier follows logically. Imagine that government spending went up by $100 and the change in real national income is $179. Then the multiplier is the ratio (denoted k) of the

Change in Total Income to the Change in government spending.

Thus k = $179/$100 = 1.79.

This says that for every dollar the government spends total real GDP will rise by $1.79 after taking into account the leakages from taxation, saving and imports.

When we conduct this thought experiment we are assuming the other autonomous expenditure components (I and X) are unchanged.

But the important point is to understand why the process generates a multiplier value of 1.79.

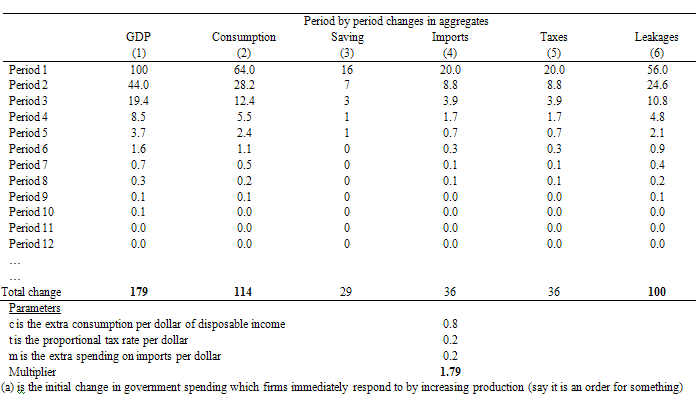

Here is a spreadsheet table I produced as a basis of the explanation. You might want to click it and then print it off if you are having trouble following the period by period flows.

So at the start of Period 1, the government increases spending by $100. The Table then traces out the changes that occur in the macroeconomic aggregates that follow this increase in spending (and “injection” of $100). The total change in real GDP (Column 1) will then tell us the multiplier value (although there is a simple formula that can compute it). The parameters which drive the individual flows are shown at the bottom of the table.

Note I have left out the full period adjustment – only showing up to Period 12. After that the adjustments are tiny until they peter out to zero.

Firms initially react to the $100 order from government at the beginning of the process of change. They increase output (assuming no change in inventories) and generate an extra $100 in income as a consequence which is the 100 change in GDP in Column [1].

The government taxes this income increase at 20 cents in the dollar (t = 0.20) and so disposable income only rises by $80 (Column 5).

There is a saying that one person’s income is another person’s expenditure and so the more the latter spends the more the former will receive and spend in turn – repeating the process.

Households spend 80 cents of every disposable dollar they receive which means that consumption rises by $64 in response to the rise in production/income. Households also save $16 of disposable income as a residual.

Imports also rise by $20 given that every dollar of GDP leads to a 20 cents increase imports (by assumption here) and this spending is lost from the spending stream in the next period.

So the initial rise in government spending has induced new consumption spending of $64. The workers who earned that income spend it and the production system responds. But remember $20 was lost from the spending stream so the second period spending increase is $44. Firms react and generate and extra $44 to meet the increase in aggregate demand.

And so the process continues with each period seeing a smaller and smaller induced spending effect (via consumption) because the leakages are draining the spending that gets recycled into increased production.

Eventually the process stops and income reaches its new “equilibrium” level in response to the step-increase of $100 in government spending. Note I haven’t show the total process in the Table and the final totals are the actual final totals.

If you check the total change in leakages (S + T + M) in Column (6) you see they equal $100 which matches the initial injection of government spending. The rule is that the multiplier process ends when the sum of the change in leakages matches the initial injection which started the process off.

You can also see that the initial injection of government spending ($100) stimulates an eventual rise in GDP of $179 (hence the multiplier of 1.79) and consumption has risen by 114, Saving by 29 and Imports by 36.

So while the overall rise in nominal income is greater than the initial injection as a result of the multiplier that income increase produces leakages which sum to that exogenous spending impulse.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 2:

When a government such as the US government voluntarily constrains itself to borrow to cover its net spending position, it substitutes its spending for the borrowed funds and logically reduces the private capacity to borrow and spend.

The answer is False.

It is clear that at any point in time, there are finite real resources available for production. New resources can be discovered, produced and the old stock spread better via education and productivity growth. The aim of production is to use these real resources to produce goods and services that people want either via private or public provision.

So by definition any sectoral claim (via spending) on the real resources reduces the availability for other users. There is always an opportunity cost involved in real terms when one component of spending increases relative to another.

However, the notion of opportunity cost relies on the assumption that all available resources are fully utilised.

Unless you subscribe to the extreme end of mainstream economics which espouses concepts such as 100 per cent crowding out via financial markets and/or Ricardian equivalence consumption effects, you will conclude that rising net public spending as percentage of GDP will add to aggregate demand and as long as the economy can produce more real goods and services in response, this increase in public demand will be met with increased public access to real goods and services.

If the economy is already at full capacity, then a rising public share of GDP must squeeze real usage by the non-government sector which might also drive inflation as the economy tries to siphon of the incompatible nominal demands on final real output.

However, the question is focusing on the concept of financial crowding out which is a centrepiece of mainstream macroeconomics textbooks. This concept has nothing to do with “real crowding out” of the type noted in the opening paragraphs.

The financial crowding out assertion is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention. At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking.

The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

At the heart of this erroneous hypothesis is a flawed viewed of financial markets. The so-called loanable funds market is constructed by the mainstream economists as serving to mediate saving and investment via interest rate variations.

This is pre-Keynesian thinking and was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

So saving (supply of funds) is conceived of as a positive function of the real interest rate because rising rates increase the opportunity cost of current consumption and thus encourage saving. Investment (demand for funds) declines with the interest rate because the costs of funds to invest in (houses, factories, equipment etc) rises.

Changes in the interest rate thus create continuous equilibrium such that aggregate demand always equals aggregate supply and the composition of final demand (between consumption and investment) changes as interest rates adjust.

According to this theory, if there is a rising fiscal deficit then there is increased demand is placed on the scarce savings (via the alleged need to borrow by the government) and this pushes interest rates to “clear” the loanable funds market. This chokes off investment spending.

So allegedly, when the government borrows to “finance” its fiscal deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment.

The mainstream economists conceive of this as the government reducing national saving (by running a fiscal deficit) and pushing up interest rates which damage private investment.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost self-evident truths. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

The basic flaws in the mainstream story are that governments just borrow back the net financial assets that they create when they spend. Its a wash! It is true that the private sector might wish to spread these financial assets across different portfolios. But then the implication is that the private spending component of total demand will rise and there will be a reduced need for net public spending.

Further, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. But government spending by stimulating income also stimulates saving.

Additionally, credit-worthy private borrowers can usually access credit from the banking system. Banks lend independent of their reserve position so government debt issuance does not impede this liquidity creation.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- When a huge pack of lies is barely enough

- Saturday Quiz – April 17, 2010 – answers and discussion

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion

Question 3:

When the national government’s fiscal balance moves into deficit, we know that the government is trying to stimulate the economy.

The answer is False.

The actual fiscal deficit outcome that is reported in the press and by Treasury departments is not a pure measure of the fiscal policy stance adopted by the government at any point in time. As a result, a straightforward interpretation of

Economists conceptualise the actual fiscal outcome as being the sum of two components: (a) a discretionary component – that is, the actual fiscal stance intended by the government; and (b) a cyclical component reflecting the sensitivity of certain fiscal items (tax revenue based on activity and welfare payments to name the most sensitive) to changes in the level of activity.

The former component is now called the “structural deficit” and the latter component is sometimes referred to as the automatic stabilisers.

The structural deficit thus conceptually reflects the chosen (discretionary) fiscal stance of the government independent of cyclical factors.

The cyclical factors refer to the automatic stabilisers which operate in a counter-cyclical fashion. When economic growth is strong, tax revenue improves given it is typically tied to income generation in some way. Further, most governments provide transfer payment relief to workers (unemployment benefits) and this decreases during growth.

In times of economic decline, the automatic stabilisers work in the opposite direction and push the fiscal balance towards deficit, into deficit, or into a larger deficit. These automatic movements in aggregate demand play an important counter-cyclical attenuating role. So when GDP is declining due to falling aggregate demand, the automatic stabilisers work to add demand (falling taxes and rising welfare payments). When GDP growth is rising, the automatic stabilisers start to pull demand back as the economy adjusts (rising taxes and falling welfare payments).

The problem is then how to determine whether the chosen discretionary fiscal stance is adding to demand (expansionary) or reducing demand (contractionary). It is a problem because a government could be run a contractionary policy by choice but the automatic stabilisers are so strong that the fiscal outcome goes into deficit which might lead people to think the “government” is expanding the economy.

So just because the fiscal outcome goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this ambiguity, economists decided to measure the automatic stabiliser impact against some benchmark or “full capacity” or potential level of output, so that we can decompose the fiscal balance into that component which is due to specific discretionary fiscal policy choices made by the government and that which arises because the cycle takes the economy away from the potential level of output.

As a result, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. As I have noted in previous blogs, the change in nomenclature here is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construction of the fiscal balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the fiscal position (and the underlying fiscal parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

This framework allowed economists to decompose the actual fiscal balance into (in modern terminology) the structural (discretionary) and cyclical fiscal balances with these unseen fiscal components being adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

The difference between the actual fiscal outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical fiscal outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the fiscal balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the fiscal outcome is in deficit when computed at the “full employment” or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the fiscal outcome into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The question then relates to how the “potential” or benchmark level of output is to be measured. The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry among the profession raising lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s.

As the neo-liberal resurgence gained traction in the 1970s and beyond and governments abandoned their commitment to full employment , the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) entered the debate – see my blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about and Redefing full employment … again!.

The NAIRU became a central plank in the front-line attack on the use of discretionary fiscal policy by governments. It was argued, erroneously, that full employment did not mean the state where there were enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available workforce. Instead full employment occurred when the unemployment rate was at the level where inflation was stable.

The estimated NAIRU (it is not observed) became the standard measure of full capacity utilisation. If the economy is running an unemployment equal to the estimated NAIRU then mainstream economists concluded that the economy is at full capacity. Of-course, they kept changing their estimates of the NAIRU which were in turn accompanied by huge standard errors. These error bands in the estimates meant their calculated NAIRUs might vary between 3 and 13 per cent in some studies which made the concept useless for policy purposes.

Typically, the NAIRU estimates are much higher than any acceptable level of full employment and therefore full capacity. The change of the the name from Full Employment Budget Balance to Structural Balance was to avoid the connotations of the past where full capacity arose when there were enough jobs for all those who wanted to work at the current wage levels.

Now you will only read about structural balances which are benchmarked using the NAIRU or some derivation of it – which is, in turn, estimated using very spurious models. This allows them to compute the tax and spending that would occur at this so-called full employment point. But it severely underestimates the tax revenue and overestimates the spending because typically the estimated NAIRU always exceeds a reasonable (non-neo-liberal) definition of full employment.

So the estimates of structural deficits provided by all the international agencies and treasuries etc all conclude that the structural balance is more in deficit (less in surplus) than it actually is – that is, bias the representation of fiscal expansion upwards.

As a result, they systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

The only qualification is if the NAIRU measurement actually represented full employment. Then this source of bias would disappear.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Saturday Quiz – April 24, 2010 – answers and discussion

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

- Another economics department to close

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I have some questions about the leakages in question 1. First on taxation- most of the taxes I pay are to state and local government- which in turn spends them back into the economy. Why is that considered a leakage? Imports- is it reasonable to assume the exporting company or country that provides what I import does not spend any of the fiat currency I pay them back into the country I live in? Saving- I understand that if I stick my savings in a box in the basement that savings is lost to the economy until I eventually spend it. But what if I bought shares in the stock market or put it in a bank that then used it as cheap funding for its loans? So I am proposing that the sum of total savings, imports, and taxes can actually, and almost certainly will, exceed the amount of the initial government increase in spending- just like the question asks. They just are not complete leakages. Had the question asked that if when the ‘leakages’ amounting from taxes imports or savings added up to more than the initial spend is that when the stimulus stops- then the correct answer might be “False”. But it didn’t. So the answer should be ‘True’ and I will award myself the coveted title of ‘MMT Friend of the People’ once again.

The answer to Question 1 is an illustration of what MMT says will happen “if government spending increases by $X dollars” etc. How well does this answer comport with what actually happens in cases that more or less fit the idealized conditions of the question?

F. Thomas Burke, the spending multiplier and its effects are not particular to MMT. I learned them years ago in econ 101. How well they hold up is the subject of some debate by economists that fantasize about ‘Ricardian Equivalence’ effects, which goes sort of like people see the government spending more so they think they will have to pay more taxes eventually, so they just save all the extra spending in order to pay the imagined eventual tax increase. Which is complete baloney.

Everybody else pretty much thinks the answer fits pretty well with reality. I think it does also.

Jerry, I may be wrong but, IStM that the answer to part of your question is —

when foreigners spend some of their income from selling to Americans back into the American economy that spending will show up automatically as part of the “export” income of Americans. Am I right?

.

Bill, I wonder if it is proper in today’s America to assume a saving rate of just 20%. Yes, this may apply to households, but does it apply to the Corps that get a lot of Gov. spending directly and even more indirectly.

. . So, I’ll illustrate this with just looking at direct payments to individuals and payments to defense contractors. I think $100 payed to people will mostly be spent at Walmart and that Walmart pockets 80% of the increase and pays just 20% more to its workers. I think Walmart gives the 80% to its top executives and shareholders who spend just 10% of it, thus saving 90% of it.

. . For every $100 in increases in Gov. payments directly to people, $300 goes to defense contractors and they behave like Walmart, that is, they give just 20% more to their workers and pocket 80% for their top execs and shareholders, who also save 90% of that new income.

. . Yes, I know the percentages are just rough guesses on my part. Feel free to change them to your guesses. I’m sure your guesses are more accurate than mine. However, please explain where my thinking is off base. Thanks, Bill.

.

Jerry Brown writes “the spending multiplier and its effects are not particular to MMT. I learned them years ago in econ 101. … Everybody else pretty much thinks the answer fits pretty well with reality. I think it does also.” It sounds good to me too. But who is “everybody else”? Apparently the people, politicians, and academic econ powers that be are not so accommodating.

If Bill’s thought experiment relies in any way on principles of MMT (beyond using common econ 101 concepts) then it essentially makes a prediction. As a thought experiment, it is a simplified and idealized *model*. If its predictions are testable, then we should be able to devise/find other models in which key variables used to calculate the 1.79 multiplier are empirically measurable — models that, while messier, are constructible from real world data but that can be mapped more or less cleanly onto or into the thought-experiment model (say, some time span in Switzerland c. 1976, or Ohio c. 1992, or whatever, so long as there is a respectable approximate fit between the idealized model and the data model(s)).

Even better, what predictions would other schools of economic theory make under the same idealized conditions as the thought experiment? Some might regard the multiplier to be a myth, but others might yield a different number. (Myself, I don’t really know.) But they all should be testable at once by the same data models. Whose numbers are closest to the actual data?

OK, maybe this particular thought experiment is not the best example to use to make this point. But I would say that something like this needs to be spelled out if MMT is to be convincing to anyone not already in “the choir” (as it were). If some comparative tests like this have been done, I would surely appreciate hearing about them.

Is it a mistake that the answer to question 1 is false. Everything you posted seems to suggest the statement is true or am I missing something?