During the recent inflationary episode, the RBA relentlessly pursued the argument that they had to…

On the path to MMT becoming mainstream

Over the last few years, it is clear that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is achieving a higher profile and the attacks are starting to come thick and fast. I see these attacks as being a positive development because it demonstrates that recognition has been achieved and a threat to mainstream ideas is now perceived by those who desire to hang on to the status quo. Hostility and attack is a stage in the process of a new set of ideas becoming accepted, ultimately. Clearly, some new interventions never receive acceptance because they are proven to be flawed in one way or another. But I doubt the body of work that is now known as MMT will be discarded quite so easily given my assessment that is is coherent, logically consistent and grounded in a strong evidence base. As part of this evolution there are now lots of what I call ‘sort of’ contributions coming from mainstream commentators. One of the ways in which mainstreamers save face is to claim they ‘knew it all along’ and that the existing body of practice can easily accommodate what might be considered ‘nuances’ or ‘special cases’. We are seeing that more now, with the more progressive mainstream economists claiming there is nothing ‘new’ about MMT that it is just what they knew anyway. Even though that approach is disingenuous it is part of the evolution towards acceptance. People have positions to protect. These ‘sort of’ contributions demonstrate a sort of half-way mentality – a growing awareness of MMT but with a deep resistance to its implications. A good example is the UK Guardian’s editorial (April 15, 2018) – The Guardian view on QE: the economy needs more than a magic money tree.

As a little historical aside – about stages in acceptance of new ‘things’ (ideas) – at the Third Biennial Convention of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America in 1919, held in Baltimore, Nicholas Klein, a delegate from Cincinnati was given the floor to “say some few words of encouragement to the Schloss Brothers strikers of Baltimore, who had been on “strike for five consecutive weeks”.

He spoke to the delegates about the strength of worker organisation and the importance of the Union.

His contribution is recorded in the Proceedings of the Third Biennial Convention of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (Baltimore, Maryland, May 13-18, 1919).

To illustrate his point, he finished with a excellent example of how social perceptions and opinions change when new ideas emerge that challenge the cognitive dissonance of the mainstream.

Here is what he said (pages 51-53):

I close by telling you the story, because I think it explains better than anything else, at this time, the great possibilities which can come to labor. There is a story told about the making of the first railway. There was an old man, it is said, whose name was Stevenson, who made the first locomotive. You know, just like in the labor movement they said locomotives were impossible. You had to have horses or cattle to pull a train; that nothing would go without something being attached to it. There would be no locomotion.

And when old man Stevenson proposed a train – something to be run without the aid of horses or oxen, he was ridiculed. One day a test was made, and they laid two pieces of wood and upon these two pieces of wood they placed some thin sheets of metal, and upon that crude arrangement was placed the first locomotive.

And it is said in the story that thousands of people were out to see the first test of that locomotive, and of course the people all shouted, and pointed to their heads, and said the man was crazy, and they said the locomotive was out of the question; it was impossible, and the crowd yelled out: “you old foggy fool! You can’t do it! You can’t do it” and the same everywhere. The old man was in the cab, and somebody fired a pistol and the signal was given. He pulled the throttle open and the engine shot out, and in their amazement the crowd, not knowing how to answer to that argument, yelled out: you old fool! You can’t stop it! You can’t stop it! You can’t stop it!” (Applause.)

And my friends, in this story you have a history of this entire movement. First they ignore you. Then they ridicule you. And then they attack you and want to burn you. And then they build monuments to.

And that is what is going to happen to the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

Relatedly, the idea of locomotives replacing horses was the subject of vigorous debate in the coal mining districts of Britain in the early part of the C19th.

This historical account from a book published in 1857 by Samuel Smiles – The Life of George Stephenson and of his son Robert Stephenson (Harper Brothers, New York) is interesting.

In Chapter VII George Stephenson’s Farther Improvement in the Locomotive – Robert Stephenson as Viewer’s Apprentice and Student – Smiles discusses the resistance in local communities to George Stephenson’s locomotives.

We read that:

… the voice of the press as well as of the public was decidedly against the “new-fangled roads.” … [the idea that] … steam-carriages … were to supersede the use of horses entirely, and travel at a rate almost equal to the speed of the fleetest horse!” … was too chimerical to be entertained, and the suggested railway was accordingly rejected as impracticable.

The “Tyne Mercury” was equally decided against railways. “What person,” asked the editor (November 16th, 1824), “would ever think of paying any thing to be conveyed from Hexham to Newcastle in something like a coal-wagon, upon a dreary wagon-way, and to be dragged for the greater part of the distance by a ROARING STEAM-ENGINE!” The very notion of such a thing was preposterous, ridiculous, and utterly absurd.

It is almost comical to read these historical accounts now.

But Groupthink, vested interests and all the related sources of resistance has been a powerful force holding back the acceptance of new ideas that are superior to the old.

The media has long been an important vehicle in giving voice to these vested interests.

Which brings me to the Guardian Editorial cited in the Introduction.

The UK Guardian maintains the myth that:

Quantitative easing succeeded in staving off disaster …

I will come back to that.

Their latest tack is that Brexit will open up new possibilities for Britain once it escapes the provisions of the Lisbon Treaty that ban central bank bailouts.

The Editor notes that Jeremy Corbyn’s early suggestion (2015) for a ‘Peoples’ QE’ was forbidden under EU membership but would become possible once Britain leaves the EU.

They don’t endorse Brexit but just “observe that the quiver of the argument against printing money might lose an arrow or two if we leave the EU”.

I wrote about Peoples’ QE in this blog post – PQE is sound economics but is not in the QE family (August 15, 2015).

The Editor observes, however, that Lisbon Treaty notwithstanding:

In fact, the Bank of England, while the UK was in the EU, did print hundreds of billions of pounds to avoid economic disaster. At the push of a button, the Bank conjured up £435bn to buy up gilts – government bonds – and exchange them for bank deposits. On the national balance sheet this sum is listed as debt, but it is not in the strictest sense because it is not owed to anyone. Turns out there is a magic money tree.

Well, in fact, that is not a factual statement.

Even a simple excursion to the – Bank of England – demonstrates the propaganda element in the Guardian’s claim.

The Bank states clearly:

The Bank of England can purchase assets to stimulate the economy. This is known as quantitative easing …

Quantitative easing does not involve literally printing more money. Instead, we create new money digitally …

Quantitative easing is when a central bank like the Bank of England creates new money electronically to make large purchases of assets. We make these purchases from the private sector … The market for government bonds is large, so we can buy large quantities of them fairly quickly.

The purchases are of such a scale that they push up the price of assets, lowering the yields (the return) on them. This encourages those selling these assets to us to use the money they received from the sale to buy assets with a higher yield instead, like company shares and bonds.

As more of these other assets are bought, their prices rise because of the increased demand. This pushes down on yields in general. The companies that have issued these bonds or shares benefit from cheaper borrowing because of these lower yields, encouraging them to spend and invest more …

No printing presses involved.

And no direct spending effect.

Whether it was successful “in staving off disaster” as the Guardian claims is another matter.

The data suggests otherwise.

The recovery really didn’t come until George Osborne curtailed his obsessive austerity pursuit and allowed the deficit to grow in 2012.

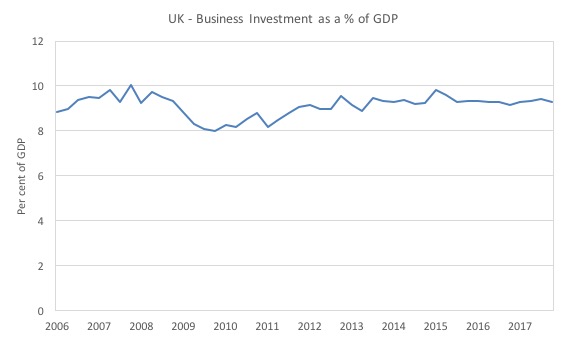

If QE had have done anything significant for the real economy, then we would have expected business investment to have picked up.

The following graph shows it didn’t do anything remarkable between 2010 and 2017. In historical terms the Business Investment ratio was around 12.6 per cent in 1998. It is now at 9.3 per cent and showing no signs of returning to the previous higher levels.

And the Guardian even recognises why, even though it wanted readers to believe that QE had done a remarkable job of saving the UK from permanent recession.

We read:

Having sold their gilts back to the Bank, investors bought up company stocks and bonds or property – sending prices to record highs – instead of creating new activity in the real economy, higher growth and jobs … The result was that the injection of money caused a stock-market boom in the financial economy, but on the real economy – the target of the policy – it had little effect.

Which makes one wonder about the editorial process at the Guardian, particularly when it comes to the so-called Editorial Comment, given the sub-title of the Editorial was that QE “succeeded in staving off disaster”.

No it didn’t. It did very little in fact. It certainly bestowed massive capital gains on holders of the financial assets that the Bank of England purchased and, in that sense, increased inequality, given the skewed nature of ownership of those assets.

But in terms of the real economy – as the Guardian concedes, “it had little effect”.

Which then brings the Editorial to the ‘sort of’ MMT narrative.

1. “Government spending, however it is financed, needs to be the main agent of recovery” – that is, fiscal policy should be the primary macroeconomic policy tool to ensure the economy maintains growth and avoids recessions.

The ‘sort of’ tag relates here to the “however it is financed” qualifier. This is mainstream resistance to the reality constraining the full exposition of what the UK government can actually do, and which was hinted at in the opening paragraph of this Editorial (when it recognised that governments can simply spend its own currency without ‘financing’).

The Editorial notes that an effective use of fiscal policy was resisted because government “ministers were ideologically resistant to” deploying it.

The Guardian then suggests what Jeremy Corbyn should do if it wanted to be imaginative:

Its plans could have seen the central bank instructed to hand over funds to a state body so it could buy services and goods without issuing debt.

The MMT solution.

Run deficits to advance well-being and only reign them if with higher taxation if the economy hits full capacity and in is danger of accelerating inflation.

The Editor sees “two objections to this” proposal:

… one is the Bank would have to pay interest on excess reserves, which would inevitably build up; or let its target rate fall to zero. Both occur today and are managed. The second is hyperinflation. Yet all spending – government or private – carries an inflation risk.

Pure MMT being espoused there.

Note the language being used – “all spending – government or private – carries an inflation risk”.

If you do a string search of my writing you will find those exact words. Pure MMT. Mainstream macroeconomists never make that essential point when talking about fiscal deficits.

They leave the readers with the impression that government deficit spending is a special category of inflation risk. It is not and the Guardian editor clearly understands that.

And in relation to the inflation risk, we get some more pure MMT from the Guardian editor:

A future chancellor could commit to using fiscal policy to make sure nominal spending keeps pace with the real capacity of the economy to produce goods and services – and withdraw the stimulus if annualised GDP growth exceeded … [that capacity].

Again, if you do a string search of my writing you will find those exact words.

This is not the way a mainstream macroeconomists talks or writes.

This way of constructing the inflation problem is pure MMT.

And in conclusion, the Guardian recognises that the UK growth is languishing and in that vein:

The lack of demand in the economy needs urgent attention. Enlarging the economy may need bigger thoughts than politicians have so far entertained.

Exactly, what the MMT economists, such as yours truly, have been saying for years now, as advanced economies have been languishing in a state of excess capacity and elevated levels of unemployment.

The point is that now we have mainstream editorials using MMT language and constructs, which I think is progress.

There remains resistance for sure. But think about that speech made in 1918 to the delegates at the Third Biennial Convention of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

The arguments and criticisms are coming up with different points now.

We are debating inflation rather than insolvency.

We are recognising the central bank can control yields and only considering the impacts of that.

You won’t find those sorts of insights in a mainstream macroeconomics textbook yet, but time is ticking. Our next textbook is due out in November 2018 and I hope it will eventually form part of the mainstream teaching curriculum in world universities.

Part of the on-going resistance to MMT ideas is the rather odd claim that the population are not capable of absorbing its implications without engaging in destructive behaviour.

This came up again from our German-friends at Makroskop who appear intent on just repeating the same assertions about the political impractability of basing policy on the principles of MMT over and over again.

I dealt with the first entreaty in this three part series:

1. My response to a German critic of MMT – Part 1 (March 26, 2018).

2. My response to a German critic of MMT – Part 2 (March 28, 2018).

3. My response to a German critic of MMT – Part 3 (April 3, 2018).

Anyway, most recently (April 16, 2018), Martin Höpner published a further entreaty – Die Debatte um MMT: Eine Nachlese.

Remember Martin Höpner thinks that there is a case for keeping the public in the dark about what the government can and cannot do with respect to its currency – maintain the lie that it can run out of money and that spending is funded by taxes – because the citizens would not be able to handle it if they knew the truth.

They would go crazy and overspend or something and chaos would follow.

I don’t think this view is grounded in an understanding of human psychology.

The most recent article reasserted his view that (translating from German and summarising – Quotes are my translations. But I am mostly paraphrasing the argument.):

1. Humans are not robots. Good start although some days I feel like one.

2. Given that MMT exposes the truth about government spending capacity and its technical limitations (real rather than financial resource constraints), the “state could do more than it pretends to do” in the advanced world.

In other words, governments lie to people about running out of money and claim elevated levels of unemployment are inevitable because they cannot create jobs without risking insolvency.

3. If governments use their fiat-currency capacity – for example “state financing via the central bank or helicopter money” and avoid accessing “capital markets” then this would rely on “the behaviour of citizens” (spending, saving, etc) being consistent with a “stable, inflation-free growth path”.

Yes, true.

And MMT advocates strengthening the automatic stabilisers which are ‘private market’ driven to allow fiscal policy to be highly responsive to changes in non-government spending and saving behaviour.

Elaborate forecasting is not required to know that there are people queuing up in the morning at a Job Guarantee agency wanting to register for a guaranteed job.

The government immediately knows its current degree of expansion is insufficient.

And vice versa, when the Job Guarantee pool is draining. The speed of that drain and the spatial distribution quickly informs government about shifts in non-government activity.

Almost on a minute-by-minute basis given our IT systems these days.

4. But Martin Höpner doesn’t think this will work because were are not robots. And his problem is that we are susceptible to confusion, scares and our “real life experiences of the functioning of the economy and thus of the money” are mainstream.

The public have no experience with the ideas espoused by MMT.

5. Which means that the idea that the state is still being responsible by “printing money” (there it is again) and spending without borrowing “is incompatible with everyday experience”.

Which means?

That Martin Höpner asserts that MMT is a “highly simplified, pre-sociological (and therefore not ‘modern’) theory of action because we, allegedly, suppose that such radical departures can be introduced without the unintended effects on the citizens”.

And what are those “unintended effects”?

Well he “does not pretend to be able to predict in detail the effects” – although he thinks people will lose confidence in the currency.

This is a repeating argument

He just asserts, again that:

… inflation … would inevitably have to break out … once the myth that governemnt spending was not revenue-constrained.

Why?

Presumably, because either the government would overspend or the citizens would stop saving (having lost confidence in the currency) and went on a spending spree.

Martin Höpner thinks both would happen.

He also thinks that the MMT notion that governments do not need to fund its spending is “practically unable to be eradicated because it is a perfect fit of our everyday experiences”.

And so it is easy for politicians to use the ‘household budget analogy’ to gain political traction over its rivals.

So there is nothing new there.

We are basically stupid, habit-driven, and unable to be educated beyond our primitive daily experience of having to go out to work to get money in order to spend. We think the government is the same and if it says it is not then we go crazy and chaos results.

I disagree with all of that.

Humans have a great capacity to learn and be educated into adopting highly sophisticated understandings.

The media is highly influential. So how many people who read that Guardian editorial would go away and resist its simple (pro-MMT) narrative?

Not many.

And in the last several years, the public has been confronted with major challenges from very senior monetary officials.

Remember, former US Federal Reserve Bank Governor Alan Greenspan’s famous admission on NBC’s Meet the Press (August 7, 2011) relating to a potential US debt downgrade:

The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print money to do that. So there is zero probability of default.

Then the next governor, Ben Bernanke, a more modern man altogether because he knows the process doesn’t involve a printing press, was asked by the US 60 Minutes program by Scott Pelley (December 3, 2010) about QE and the growing fear that it would unleash an inflationary spiral.

The transcript included this Q&A (Source):

Pelley: Many people believe that could be highly inflationary. That it’s a dangerous thing to try.

Bernanke: Well, this fear of inflation, I think is way overstated. We’ve looked at it very, very carefully. We’ve analyzed it every which way. One myth that’s out there is that what we’re doing is printing money. We’re not printing money. The amount of currency in circulation is not changing. The money supply is not changing in any significant way. What we’re doing is lowing interest rates by buying Treasury securities. And by lowering interest rates, we hope to stimulate the economy to grow faster. So, the trick is to find the appropriate moment when to begin to unwind this policy. And that’s what we’re gonna do.

Okay, no printing presses.

QE lowers interest rates only.

Lower interest rates may or may not stimulate spending depending on a host of other things including the state of confidence, unemployment dynamics etc.

We also might recall an earlier interview between Scott Pelley and Ben Bernanke on the US 60 Minutes program (March 12, 2009) – Ben Bernanke’s Greatest Challenge .

The interview is largely a litany of mainstream statements but at one point Bernanke provided a very clear statement about how governments that issue their own currency actually spend.

At around the 8 minute mark of the segment, Bernanke starts talking about how the Federal Reserve Bank (the US central bank) conducts its ‘operations’ (in this case, how it conducts government spending).

Interviewer Pelley asks Bernanke (Source):

Is that tax money that the Fed is spending?

Bernanke replied, reflecting a good understanding of what we call central bank operations (the way the Federal Reserve interacts with the member banks):

It’s not tax money. The banks have accounts with the Fed, much the same way that you have an account in a commercial bank. So, to lend to a bank, we simply use the computer to mark up the size of the account that they have with the Fed. It’s much more akin to printing money than it is to borrowing.

That is, the US government spends by creating money out of ‘thin air’.

And we have now lived through nearly a decade of major shifts in government policy.

Large deficits to stimulate growth – working.

Massive expansions of central bank balance sheets (QE) in the UK, Japan, Europe, the US – all accompanied by the sort of claims that Martin Höpner is making (although he does it more politely) that hyperinflation would result and currencies would be trashed.

We have observed none of those things happening.

And has our behaviour changed dramatically? Not in any unpredictable (broadly) ways.

When unemployment started rising we increased our saving ratios – as you would expect.

When the fiscal stimulii started to work – we loosened our spending again – but modestly.

Investment has been slow to pick up because it is asymmetric due to the irreversibility of capital formation. All as expected.

Borrowing didn’t go through the roof at zero interest rates. Why not? Because credit worthy borrowers were cautious in the milieu of high unemployment and previous credit binges.

And, of course, the Japanese have been going through this process for a quarter of a century. They have seen credit rating agencies embarrassed as they downgrade Japanese government debt to junk status only for the public to observe nothing of consequence follows.

They have seen on-going deficits, low to zero interest rates, low inflation (bordering at times on disinflation), high gross public debt levels.

I haven’t seen major behavioural shifts in the economic behaviour of Japanese residents.

In fact, as I noted in my three-part response to Martin Höpner, destructive non-government behaviour accompanied the intensification of the myth narrative about fiscal deficits and the promotion of fiscal surpluses.

We had credit binges, criminal behaviour by our financial sector, and then crisis.

Conclusion

The UK Guardian Editorial is a sign of progress. One small step as they say.

But for years we were ignored – “you old foggy fool! You can’t do it! You can’t do it”.

Then we were ridiculed – “you old fool! You can’t stop it! You can’t stop it! You can’t stop it!”

and whenever, we might become mainstream.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Well, professor David Harvey said that you can have a great time going off collecting evidence of that sort of things of contemporary society as scientist get in and start to tell you how the social world should be organized without even understanding that they draw metaphors from the social world to construct the social world.

Dear Bill,

If I may be allowed to simplify, MMT is based on an accounting perspective on the macro-economy (sectoral balances etc.). It is in essence descriptive. It can predict the future only if the future evolves along previously observed trajectories. But that is by no means guaranteed.

While Höpner does not build a strong case, you can’t use MMT’s methodology to rule out the possibility of unintended consequences. The evidence for such a possibility is available in recent history. I can’t be the only one to notice that the moment in which the U.S. adopted a fiat currency was the same one in which element in the conservative elite began to organise a political programme that culminated in the neo-liberal order in which we are currently living.

To be more specific, Nixon issued Executive Order 11615, closing the gold window, on 15 August 1971, and eight days later on 23 August, Lewis Powell was commissioned to write his famous memo. This may be a pure co-incidence, but the upshot of these events was that the power of fiat currency to further the well-being of American citizens was never fully realised, not simply because of outdated habits of thought on the part of politicians and monetary authorities, but due to a deliberate campaign of resistance: an unpredictable behavioural consequence of a change of monetary regime, that can only be accounted for retrospectively in a framework such as that of MMT.

Two points if I may.

“Their latest tack is that Brexit will open up new possibilities for Britain once it escapes the provisions of the Lisbon Treaty that ban central bank bailouts.”

If there is a deal it would have to include this restriction otherwise it puts Britain in an advantageous position, so it only works if there is no deal which is extremely unlikely. Although, of course, the EU negotiators might be so stupid that they do not realise the importance of the clauses, such as Article 123, that are designed to protect the common currrency.

“If you do a string search of my writing you will find those exact words.”

How do you do a string search? I have often typed in the search box but it comes up with hundreds of hits all of which contain any of the words I have typed. Even then it only goes to a articles which contain one of the words and I have to search through the text to find it.

@Nigel: Have you tried putting the string inside double quotes? I’m not sure offhand what string was being referred to here, but I tried with a couple of test strings, and it appeared to give the desired result.

@Nigel (again): Funnily enough that exact phrase – “all spending – government or private – carries an inflation risk” – Does not actually get any hits (except for this article). But variations of it do: e.g. “carries an inflation risk” – include the double quotes.

Dear Bill

You and Heiner Flassbeck are my favorite economists. Herr Flassbeck wrote an article in Makroskop “Was ist zu kritisieren an der MMT?”, in which he argues that the 2 weaknesses of MMT are its unconcern about flexible exchange rates and the fact that it doesn’t take into account the possibility that there can be inflation with the Job Guarantee. I thought that he made a good case.

Regards. James

If NMT is engaged then because it reflects the real world it can be justified and attacks will demonstate the foundational weakness of the neoclassical “belief”

I think that Guardian article, flawed as it was, indicates a shift. It certainly surprised me. I gave a little smile. A change is gonna come….

I’m sure you know, but Herr Flassbeck may not know, that MMT experts always say that the Job Guarantee is actually counter-inflationary, as it provides an anchor for wages.

I’m not an MMT expert, so I can’t be quite as confident about this as they are. But I am a believer in testing/experimenting/prototyping, where possible.

It’s hard to know though how this theory could be tested. We do have the example of the New Deal in the USA, which “worked” as far as it went, but it wasn’t quite a JG scheme. and anyway, the world has changed a lot since then.

I’m not sure if anything like the JG has actually been tried (perhaps on a small scale) elsewhere.

On the other hand, it’s not clear that small scale tests would actually tell you very much, although it might help to “rehearse” some of the admin-type procedures, and get a feel for how receptive potential JG job-takers would be. (But would it be morally justifiable to recruit someone for a JG job, if the scheme might not carry on in perpetuity?).

I have a feeling that the main problems with JG will not be to do with inflation, but practical matters like exactly how it will be administered locally. Central government will have to provide the finance not just for the jobs, but for the admin function (which will have to employ new people, since local government is already overloaded, at least in the UK). These people will need the right sort of skills, and will such people be available in sufficient numbers? (a real resource constraint).

David Leonhardt in today’s NY Times Opinion email blast gives Stephanie Kelton a positive mention but loses the plot rather spectacularly here, ” . . . . financial markets would at some point begin to punish the United States government, out of a legitimate fear that it wouldn’t be able to repay its debts. Borrowing would become more expensive for this country, and our economy would suffer.”

Clearly, MMT ain’t quite there yet.

@CS,

“I think that Guardian article, flawed as it was, indicates a shift. It certainly surprised me. I gave a little smile. A change is gonna come….”

Is the general consensus that it was written by Larry Elliot?

(Because, if not, it would be interesting to know who else may have written it.)

“Central government will have to provide the finance not just for the jobs, but for the admin function ”

They already have in the UK. They are called ‘Work Coaches’ and already exist in the Job Centre Plus system. All the infrastructure is there as part of the Universal Credit roll out.

What we need to scale is the work creation function – which again exists in prototype form as a service to the Probation system. That gives the Job Guarantee the ability to create jobs to match people. That then augments the current Universal Job Match system to deal with existing vacancies – the traditional matching people to jobs.

On the payment side, all you need is a flag on the PAYE RTI system that allows authorised employers to file nil paid timesheets, which would then be paid at the living wage via the Universal Credit systems.

If you get inflation with a Job Guarantee you’d get inflation with an unemployment buffer in much the same way (more so in fact) – because they use the same control mechanism. It works better under a Job Guarantee because it is double dampened – individuals working are far better substitute hires, and the Job Guarantee is a far better substitute offer than the dole.

Bear in mind that Universal Credit already allocates you a job. You have to spend 35 hours a week looking for jobs that can’t exist.

We can do better than that.

MrShigemitsu

Probably Mr Elliot. But what is key here is that it was the “Guardian view” which means the paper on a broader scale is accepting MMT ideas (yes I know the article was flawed) as “the way forward”. Better late than never. A Corbyn government will need to have MMT as the prevailing zeitgeist in the progressive economic mind to allow it to do what it wants to do.

A lot of my progressive friends won’t listen to me about MMT (Zimbabwe/Weimar/burdening our grandchildren) but when the Guardian pronounces something as worth listening too, they listen.

Sad but true.

A modification of the famous quotation from 19th century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer:

Widely accepted truths often got there through three stages. First, they were ridiculed. Second, they were questioned. Third, they were regarded as unoriginal and obvious.

Dear Tyler (at 2018/04/18 at 6:04 am)

Often stated, but there is no evidence to trace that quote back to the texts of Schopenhauer.

best wishes

bill

As we were discussing the Job Guarantee earlier, I thought people might like to see this article on UBI by Ellis Winningham (of Real Progressives): he calls it a An Economic “Destabilizer”.

http://elliswinningham.net/index.php/2016/05/23/universal-basic-income-an-economic-destabilizer/

I’m sure Bill has already said all this and more in various articles maybe in slightly different ways, but I just happened to find this, thought it was quite good and quite short, and possibly something to point to for people who are still convinced by UBI.

[MMT] doesn’t take into account the possibility that there can be inflation with the Job Guarantee. I thought that he made a good case.

Well, Bill always says that “all spending carries an inflation risk” 🙂

So the question should not be seen in absolute terms, but rather in relative terms. How does the inflation risk due to JG spending compare to other solutions to demand deficiency?

Solutions I am aware of are: encourage borrowing; cut taxes; public works and defence spending; unemployment benefits; income guarantee.

It is not hard to convince yourself that JG has better inflation controls than any of the above, mainly because it is self organising, does not compete for labour, produces real wealth and sustains human capital.

@Brendanm et al:

There are two new (I think) papers from Levy, one by Pavlina Tcherneva, and the other co-authored by her, Randall Wray, Stephanie Kelton, Scott Fullwiler, and Flavia Danta about the Job Guarantee / Public Service Employment Program.

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_902.pdf

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/rpr_4_18.pdf

Also, a shorter “policy note” by the same group:

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/pn_18_2.pdf

One of the conclusions of the 2nd paper is:

(Among other macroeconomic analysis of the impact of a PSE program).

Mike Ellwood says:

Tuesday, April 17, 2018 at 21:40

Thanks for that Mike. That does seem to take you to a document containing the string but you still have to scroll through the whole text to find what you are looking for. I suppose you could copy the whole thing, paste into Word and then search but that would be a bit tedious.

QE is simply a tax on business.

They haven’t printed new money at all, even electronically. They have enforced deposits from commercial banks to take a below market interest rates, which is essentially a tax on lending.

When a monetary institution is faced by a rise in interest rates, it doesn’t deposit more with a central bank, it seeks lower valued higher yielding assets that match the term of their lending as the risk to these assets diminish.

Unwinding QE is not cataclysmic, it is technical function that really has little effect on the general populace.

People QE, stifles private investment and creates stranded assets. Unwinding peoples QE, should it fail, would be cataclysmic.

Bill have you considered finding a simple step toward a goal, rather than big principles?

If you can prove that part of the process works, you can make changes. Don’t think big, think small and easy.

Small gains are hard won, decades not years. To start the process you need to think what step 1 would be.

@Nigel,

I don’t know what you are using to read the blog, but I’m normally using Chrome on a desktop.

Using that, I can search through an article (or any webpage) using CTRL+f (“find”), and type or paste the string into the search box that comes up in the top right. I’ve just tried this with another article and another phrase and this worked ok. In this case, I didn’t need to put the string in quotes.

hmm….just tried it with quotes, and it didn’t work. So the lesson seems to be that search within the page you are currently on does not need quotes, while searching the whole site may well need quotes.

I’m not sure about any of this regarding mobile devices. I do read the blog on my phone sometimes, but I don’t think I have attempted searches on it from the phone.

This seems a strange way of looking at it.

They had to create new money with keystrokes to buy the assets. Bernanke and the BoE have told us so. But as the money goes straight into reserves and not into general circulation, it doesn’t increase the general money supply.

As indeed QE was, and did; In other words, it was a colossal waste of time as far as the general populace was concerned.

I think you need to provide some evidence for that statement.

And tell us what a “stranded asset” is.

The notion that MMTists do not consider and have not consider the ‘implications’ of OMFG (Overt Monetary Financing of Government), given flexible/floating exchange rates is truly preposterous.

Equally preposterous are claims that the JG/PSE has an “inflationary” potential effect which, allegedly, the proponents thereof are ignoring or not giving enough or due consideration to.

People might as well accuse proponents of general ‘electrification’ of “ignoring” the increased risks of “death by electrocution” consequent upon generalized electrification of a territory. Or proponents of mass literacy of ‘ignoring’ the increased risks of person-hours of potential vigorous and productive manual labor being lost consequent upon the generalized enabling of persons to “waste their time” reading frivolous romance novels or pessimistic philosophical disquisitions.

GrkStav- Well said! Hilarious as well! Thanks for brightening my day.

With Regard to the inflation risk of policy prescriptions based on MMT analysis:

What people rarely take into account is the added production of goods and services by private sector business people who go waky waky when newly-working folk wave their pay checks in front of their noses. The added goods and services offset newly issued money resulting in —-> no added inflation. The key is added spending when there are excess resources (unemployed folk) in the economy, a task which the Job Gty is ideally suited for. (Can someone cite one academic paper where this is pointed out?)

GrkStav: Indeed. MMT doctrine on flexible/floating exchange rates, the JG/PSE and on inflation are not weak points, but strong points. Things that MMT writers have treated in great detail, not skipped over. The (range of) MMT positions are the only coherent, consistent and common-sensical ones.

People might as well accuse proponents of general ‘electrification’ . . . of mass literacy etc.

Yes, but it is also very amusing that all such actually were once quite literally opposed that way- socialist measures like post offices (“The Evils of State Trading, as Illustrated by the Post Office”), public libraries that lead to reading romance novels, and electrification etc in the following book, for one:

Thomas Mackay, Herbert Spencer- A Plea for Liberty: An Argument Against Socialism & Socialistic Legislation- Appleton (1891). (Look for more such good fun reading at the Mises Institute.)

The well-meant, friendly criticism of MMT is founded, buried deep down, on ideas which are as crackpot as Mackay & Spencer’s et als. Ideas which are inconsistent with the friendly critics’ own often valuable works, because the friendly critics have not thought things through as well as MMTers, not come up with theories as internally consistent (and externally, practically applicable) as MMT. Crackpot ideas which in a few years almost everyone will find as hilarious as they now find Mackay & Spencer & the Mises Institute’s diatribes against modern public conveniences as an attempt to set up a socialist Incan empire in Britain.

No, it is NOT good to be ruled by exchange rate obsessions, to distort your domestic economy in order for the foreign sector tail (and “the so-called international bankers”) to wag the domestic dog.

No, unemployment = people not doing stuff, does NOT lead to prosperity and wealth = more stuff being done or having being done. So not having a JG is and always was a crackpot idea, so anything that prevents it, like exchange rate obsession is also harebrained.

The key for me is not understanding this as a scientific or even ideological debate.

It is all about power.In scientific terms mainstream economics is an emarresment

with zero evidence to support it .This is true at the micro as well as the macro level.

It is a fig leaf for power.If MMT challenges individuals power,wealth and their ability

pass them on to their children then MMT is their enemy.

So if state monetary sovereignty becomes transparent then inflation will be the

chosen weapon.So yes as Bill says MMt wants to move the debate from debates

about state insolvency to inflation control but do not expect mainstream economics

to be any more coherent understanding inflation than understanding state monetary

sovereignty.

Now that Cuba has a new, youngish leader could someone make the trip to Cuba and educate him on MMT?

@RoswellJohn,

Good thought. But from the report I read, it seems that Raul Castro will still be the power behind the throne for as long as he lives/still has his faculties. But also aren’t the Chinese very well connected in Cuba these days? They operate by a “kind of” version of MMT don’t they? It would be interesting to know if they have any economists talking to him.

Bit late to the show but the answer to the searches question is to use plus signs.

carries inflation risk : will find pages with any of those words, ranked in a secret way by the algorithm

“carries inflation risk” : will find pages that include all of those words in exactly that phrase

carries+inflation+risk : will find pages that include all of those words in any place in the text, not necessarily together

The mainstream bogeyman is tiresome. Does anyone really know anyone who thinks government spending more inflationary than any other type of spending?