I will be working in the UK from February 19 to February 28, 2026. I…

Running trains faster but leaving more people on the platform is nonsense

Earlier in the week I was in Britain. Walking around the streets of Brighton, for example, was a stark reminder of how a wealthy nation can leave large numbers of people behind in terms of material well-being, opportunity and, if you study the faces of the people, hope. I am used to seeing poverty and mental illness on the streets of the US cities but in Brighton, England it very visible now as Britain has struggled under the yoke of austerity. Swathes of people living from day to day without hope under the current policy structures, damaging themselves through visible alcohol and substance abuse, cold from lack of shelter and adequate clothing, and the rest of it. And then a little diversion around the City area of London, where the overcoats the men wear cost upwards of £2,000 and the faces are full of intent. Two worlds really. I was thinking about those recent experiences when I read the latest release from the IMF (September 20, 2017) – Growth That Reaches Everyone: Facts, Factors, Tools. Their analysis continues the slow move of the IMF to acknowledging, not only the reality the world faces, but also, by implication, the massive costs that this institution has inflicted on poor people around the world.

I reflected on the street poverty in England in this blog – 17 inch-long pigeon spikes – out of sight, out of mind.

I have written about inequality before (among other blogs):

2. The rise of non-standard work undermines growth and increases inequality.

3. Rising inequality demonstrates we haven’t learned much.

4. Trickle down economics – the evidence is damning.

The IMF started banging on about ‘growth-friendly austerity’ at the height of the GFC as a means of defraying their own culpability in the disaster.

Their ideological outlook required them to persist with their austerity obsession, in partnership with the European Commission and the European Central Bank, but the results of their interventions were increasingly negative and significantly so.

The politics and public relations disaster of the orchestrated demise of Greece under the control of the Troika, doing the work of Germany, became intense and so the IMF had to make up this ‘growth-friendly austerity’ nonsense to allay public discord.

They wanted us all to believe that hacking into public spending in a nation that was already enduring a collapse of private spending would suddenly defy all economic understanding and spring into a new period of growth.

It was surreal following and commenting on this at the time. It was like a game that you might play with kids and show them an orange and tell them it was an apple.

But, kids are smarter than us, it seems, because they would never fall for that.

The rest of the world did fall for the IMF ploy. Why do I say that? Because we continue to support them via the funding from our sovereign governments. No IMF official has has been prosecuted for professional malpractice over the disastrous modelling that they finally admitted was wrong in relation to the Greek bailouts.

No-one gets sacked for the systematically hopeless forecasts the IMF pumps out. And more.

But the ‘growth-friendly austerity’ story fell apart pretty quickly as nations enduring austerity went further backwards.

At the same time, progressives seized on income and wealth inequality as an agenda to pursue, having rendered themselves innocuous in the macroeconomics debate through their acceptance of the overall neoliberal economic myths that underpinned the austerity push in the first place.

So it was all inequality, inequality, inequality – and ‘tax the rich’ type policy slogans, which, presumably, made everyone on the Left feel better a bit but grossly missed the point – that taxing the rich gave the state any extra funds that it already had as a result of its currency monopoly.

We might want to increase taxes on the rich because we think they have too much purchasing power (a moral story!) or for some other reason, but never would we want to do that to raise ‘funds’ for the government to spend.

So the progressive push just goes down the sinkhole of irrelevance.

But the IMF is also making further moves towards reality in their own recent interventions in the area of inequality.

The September statement (cited above) says:

Economic growth provides the basis for overcoming poverty and lifting living standards. But for growth to be sustained and inclusive, its benefits must reach all people.

While strong economic growth is necessary for economic development, it is not always sufficient.

This issue came up in my presentation in Brighton (England) at the fringe British Labour Party Conference event. A ‘Green’ concern was expressed about the imperative zero growth.

I argued that with rising population growth and continued abject poverty in the world we had to continue to have economic growth (real GDP rising).

But the challenge was to make that growth environmentally sustainable and, as the IMF now recognise, inclusive.

It just doesn’t make sense to run the trains faster and leave an increasing proportion of passengers behind on the platform.

The growth at all costs mantra that dominated the IMF in the past seems to be becoming modified by the inclusive notion.

The IMF research now:

… makes it clear that persistent lack of inclusion-defined as broadly shared benefits and opportunities for economic growth-can fray social cohesion and undermine the sustainability of growth itself.

In other words, the ‘trickle down’ mantra that dominated the early years of this neoliberal era does not accord with the evidence.

You need to worry about distribution as well as levels of national income to maintain growth in the levels.

Feeding the rich does not provide scraps for the poor.

The IMF detailed their work in a paper prepared for the G-20 Leaders’ Summit in Hamburg, Germany (July 7-8, 2017) – Fostering Inclusive Growth.

It outlines several ways in which “high and persistent inequality” undermines “longer-term growth and macroeconomic stability”.

1. “high inequality can be destructive to the level and durability of growth itself … weaken support for growth-enhancing reforms and spur governments to adopt populistic policies, threatening economic and political stability”.

2. “High inequality can yield a less efficient allocation of resources” which means that the poor will not receive sufficient education and training and thus the nation loses the potential embodied in that cohort.

Studies show that if opportunities to participate in education and training are restricted by income class and so ‘less able’ rich people gain qualifications at the expense of ‘more able’ poor people, then the overall skill levels that are developed are lower and the nation suffers as a result.

3. “Inequality resulting from high unemployment can impose large economic costs” – unemployment is the largest inefficiency there is and dwarfs all the things neoliberals rave on about (buses running a little late, etc).

There are huge daily losses to a nation in terms of lost output and income from mass unemployment. That has been one of the craziest things about this neoliberal era – the willingness of policy makers to tolerate (and maintain) huge pools of underutilised labour while demanding public enterprises are privatised (for example) to make them more ‘efficient’.

4. “Inequality can also cause social conflicts”.

5. “Inequality and unemployment can impair individuals’ ability to cope with risk and thus increase macroeconomic instability” – the irony of neoliberalism is that it claims it wants to reduce the community’s reliance on welfare yet creates a larger pool of people who only have income support standing between them and starvation.

By sustaining mass unemployment, neoliberal policies force the state to also increase its welfare spending, given that most societies haven’t yet got to the stage of exterminating those without work. That is, yet!

Recall this blog – L’horreur economique – where I reviewed a disturbing book written by the French writer Viviane Forrester.

In her 1996 book called L’horreur Economique about unemployment (you can get the 1999 English version – HERE – essential reading) – she proposed that governments are failing to generate enough employment but at the same time they are promoting a backlash against those who are jobless.

Viviane Forrester wrote:

The panaceas of work-experience and re-training often do nothing more than reinforce the fact that there is no real role for the unemployed. They come to realize that there is something worse than being exploited, and that is not even to be exploitable …

The book ventures into the notion that governments (elected by us) have made the unemployment dispensable to ‘capitalist production and profit’ and have instead been content to keep them alive. But soon, why would it not be implausible to declare this growing group of disadvantaged citizens totally irrelevant.

The proliferation of jobless vagrants in Brighton (England) are irrelevant to the mainstream British society.

We allow our neoliberal governments to claim there is not enough ‘money’ to solve all these problems.

But if the unemployed and homeless are ultimately dispensable for capitalist production (and that is what persistent long-term unemployment suggests); and they cannot do anything productive if we employ them in the public sector (that is the overwhelming view of the deficit terrorists); and they are a nuisance to manage (you know all the arguments – income support corrupts etc) – then ultimately society might start asking “what is the point of the unemployed?”.

That is the disturbing question that Viviane Forester poses.

She postulates that then different solutions might be advanced such as getting rid of them altogether. Don’t think this is off the track … after all only 70 odd years ago Germany decided that a definable cohort was dispensable and could be exterminated.

I am writing this from Berlin!

L’horreur Economique is one of those books that you just go back to from time to time to remind yourself of the message.

The IMF research now establishes two key propositions as being firmly evidence-based:

1. “high inequality is … negatively associated with sustained growth”.

2. “the duration of growth spells is negatively related to the initial level of inequality”.

That is, according the way in which we accept ideas as knowledge, these propositions are factual rather than just opinion.

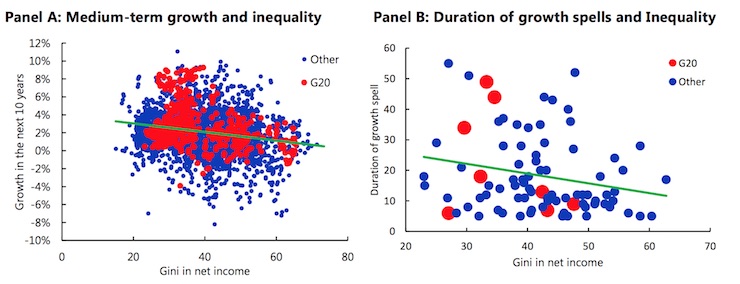

The following graph(s) is taken from Figure 1 of the document cited above which shows the evidence generated to support the statements.

The left panel provides support for the first statement. The horizontal axis shows increasing inequality (measure by the Gini coefficient), while the vertical axis is a measure of real GDP growth (over an extended 10-year horizon).

The data covers the period 1960 to 2010.

The observations cover G20 nations (red) and others (blue).

There is a clear negative relationship (the green average regression line).

The right panel has the same horizontal axis and colour code but the vertical axis shows how long the growth spell endures once underway.

The right panel provides support for the second statement.

The IMF also distinguish between “inequality of outcomes (ex post) and inequality of opportunity (ex ante)”.

So income is usually the outcome measure that is focused on, and the evidence is clear:

… inequality between countries is still higher than inequality within countries … almost two-thirds of global inequality is still attributable to per-capita income gaps between countries.

Which shows one how deep the problem is, given that the top 1 per cent of the income distributions within countries have enjoyed massive growth in income at the expense of lower income cohorts and that “Within-country income inequality has

been on the rise until the mid-2000s, especially in advanced economies.”

Further:

In many countries, a disproportionally large share of income has accrued to the top 1 percent of the income distribution … [and] … the average labor share of income has declined in many countries, particularly among low- and middle-skilled … The decline in the global labor share of income has generally implied higher income inequality

These trends – within-countries – have been large. So the disparity between-countries have been larger and an indictment of the failure of the neoliberal era.

The IMF also find that “Wealth is distributed more unequally than income” and, as is often noted, wealth provides access to power and influence.

And so the cards are stacked against those at the lower income and wealth classes which excludes their voice from the policy making process.

Conclusion

I am off to Madrid this morning (currently in Berlin) so that is all I can write on this today.

Reclaiming the State Lecture Tour – September-October, 2017

For up to date details of my upcoming book promotion and lecture tour in Late September and early October through Europe go to – The Reclaim the State Project Home Page.

Last night’s event in Berlin was very well attended and the discussion was interesting.

Tonight’s public event is in Madrid. I have other engagements in Madrid in addition to this.

Speakers:

- Professor William Mitchell, Author Reclaiming the State.

- Thomas Fazi, Co-author Reclaiming the State.

- Dr Eduardo Garzón, Adviser in the economic cabinet of the Economy and Finance Area in the City of Madrid.

- Manolo Monero, Parliamentary Deputy for United Podemos.

Location: Ecooo, Calle Escuadra 11, 28012, Madrid, Spain.

Time: The event will start at 18:30.

Entry: Free. All are welcome. A small donation will be appreciated by organisers to cover room hire.

For further details: E-Mail Stuart at redmmt.info@redmmt.es or madrid@redmmt.es

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“and, as is often noted, wealth provides access to power and influence.”

It does, but that is often a one way gate since death provides access to the network of power and influence.

The mistake is to believe that taking the wealth away reduces the power and influence. Actually it is likely to reinforce the power and the use of power because the network of influence would see itself under attack.

Which just shows that ‘tax the rich’ is an emotional response. But it may be an emotional response that is useful, since it opens the door to the more rational rich. If they feel under threat again then they may be more likely to talk about an accommodation.

Luckily, the unemployed have an important function in society- they are there to temper wage demands of the already employed. And they serve as examples of how much worse off you could be if you weren’t employed. So the people in charge are not interested much in getting rid of the unemployed, or helping them either. Now if they figure out how to kill them and make a profit doing so that might change very quickly.

Parts of this post remind me of the panel discussion you were part of at UMKC recently. You were there with Stephanie Kelton and Warren Mosler and Randy Wray I think. I was only able to see part of it on the live streaming thing, but wasn’t able to hear most of that. Do you know if there is somewhere I can see it again?

The degree of shift in income (and wealth) towards the small minority rich is composed of several factors – certainly the GFC is pre-dominant; failure to adequately tackle this is widely apparent (as Bill implies with his observations in Brighton and elsewhere).

There are other factors involved that need to be taken seriously into account too – for some time, the former industrial nations of the western world have been adjusting to changes in world trading patterns; employment and earning capacities have had to adjust accordingly. These trends and associated biases (subsidies, etc) are not yet fully appreciated or tackled.

Up to now Bill has made passing reference to these influences but perhaps he needs to explain more fully the impact that open world trade has on the ability of sovereign nations to protect their population from the income (wealth) effects of open trade borders – or alternatively, point to where he has explained economic (and/or ideological remedies) among his vast output.

I wish I had the time to absorb more of it!

I am fascinated by your line of thinking which as a lay person in economics (but interested in investing) I am still coming to grips with. I do think people should look at your work more closely.

You write: ” So it was all inequality, inequality, inequality – and ‘tax the rich’ type policy slogans, which, presumably, made everyone on the Left feel better a bit but grossly missed the point – that taxing the rich gave the state any extra funds that it already had as a result of its currency monopoly.

We might want to increase taxes on the rich because we think they have too much purchasing power (a moral story!) or for some other reason, but never would we want to do that to raise ‘funds’ for the government to spend.”

And from what I understand on some of your comments on Japan, you are not particulary in favour of higher taxes (economically; moral etc. might be a different matter as you allude to) – you believe fiscal measures can achieve many of the goals of government.

But, can you point me to where you describe what tax policies you would advocate? I shall try and get a copy of your book. Hope you had a good trip to UK and Germany etc.

Bill, I too had a stroll around Brighton for an hour or so, and I can’t say as I saw what you say you did. In fact I found the place to be vibrant. Indeed, my travelling companion commented as such even as we walked out of the station concours.

Here, a hundred or so miles west, I go around the town seeing huge and numerous construction projects and people going about their business with a growing sense of urgency. There are beggars in the street, but not more, as I recall, than usual – there will always be a section of the community who make that choice.

What, unfortunately, you don’t see is all the disabled and elderly people who are being let down by the lack of social care. I am right now particularly conscious of this because I live in a retirement, or assisted living, apartment, and when I arrived home from Brighton I noticed the neighbour’s mail had not been extracted from the letterbox. Next morning it was still there so another neighbour alerted the emergency services. They arrived an hour and a half later (!) to find the lady dead. She had been unwell for some months and was trying to get into a care home without success.

In the UK social care is funded by local authorities from council tax with a top-up from cnetral government. For the duration of the austerity period government funding of local authorities has been savagely cut and, as from I believe 2018, it will be withdrawn altogether – albeit they will be allowed to keep business rates from that date which will cease to be collected by the Treasury. Consequently there is a post-code lottery as to what care you get, which anyway is inadequate wherever you live. I have today signed a petition calling on the government to fund social care via the NHS.

@ Nigel Hargreaves

Brighton is indeed a vibrant community but there is no question that the level of street homelessness has massively increased over the last few years. Coming in on four consecutive days, I was a bit shocked to see the same people, in the same places, on every day. As Bill says, the ravages of alcohol and probable drug misuse, were all too evident. I said (rather uselessly) to one of the blokes who’d set up ‘home’ next to the barred and gated car park, that things shouldn’t be like this for him and he murmured back that ‘the government didn’t care’. Too right. He knew that he was dispensable.

Nigel Hargreaves, I came down to Brighton for the fringe event Bill was addressing. One of the first things I saw was some sleeping bags and cardboard boxes in front of the low-cost supermarket on the left hand side going down the hill from the station. Brighton is indeed vibrant. I live very close to the City of London (just over the bridge) and it too is vibrant. But you need to walk round with blinkers on not to see the grey world of misery – scattered through those vibrant places – enveloping those who sit wrapped round with their personal possessions where they hope sufficient folk with a bit of compassion might pass them some spare change.

Nigel

Sorry to hear that your neighbour passed away.

“they will be allowed to keep business rates”

This is just a money grab by the rich, Tory-controlled local authorities. The rates used to be collected into a central pot and then divvied up according to need. Have a look at this chart in The Guardian to see which local authority will benefit the most from the new scheme (clue: it’s where Bill saw those people in the £2,000 overcoats) and which authorities will be crippled.

Nigel

“there will always be a section of the community who make that choice”

I’m not sure it is they who are making the choice. The right choice is being made in Albuquerque. It’s a Job Guarantee and it works.

Bill has indeed written about inequality before – blogs listed at the top of this page contain item 1- Reducing Inequality https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=34118, which refers to some salient material relating to the setting of wages in international trading nations.

He refers to a so-called ‘Scandinavian Model (SM)’ of inflation that can be applied to national wage setting principles, particularly in small economies that are exposed to international trading markets.

He concludes however, that the dynamics of the unfettered labour market will continue to increase income inequality.

What is unclear, at least to me, is the impact that full employment policies might have on a sovereign nation’s ability to maintain living standards within an open international trading system, especially if productivity cannot be maintained at a global level.

The dexterity a government can employ maybe critical; affecting the pace of innovation, the pace at which education and technical expertise is capable of being exploited, and the ability of financial resources to respond to opportunities.

Underlying all this advancement is the basic human predisposition to compete; and that historically has always involved winners and losers, profits and losses, and human achievement and suffering.

Nigel, really, “a selection of the community that makes that choice” to sleep on the street? There’s no choice involved.

Please come to Auckland, New Zealand, and witness people living in garages and cars with their babies and toddlers, while the rent for a villa in Ponsoby is $1,200pw.

Matt B. There are a small (admittedly very small) number of people who do choose to sleep on the street. Have you heard of the book “Diary of a Supertramp”? I am not in any way suggesting that all the people who live on the street do so by choice. I went to a hustings meeting for the recent election and returning late that evening I passed six people huddled up in doorways. That’s a disgrace.

I was just trying to paint a picture of the other side of the coin lest a reader in New York or Sydney might get the impression that the entire population of Great Britain is “behind in terms of material well-being, opportunity and, if you study the faces of the people, hope”. I don’t see that around me, at least not in “large numbers”.

“I don’t see that around me, at least not in “large numbers”.”

Anything above zero is too large a number.

The decline of the social care function in UK society not only affects the elderly. It stains all of us.

Arriving in Brighton for Bill’s talk was indeed depressing.

It’s always had a bit of a reputation for being a bit of a Skid Pan Alley, but I too sensed an increase in the indigent population around the environs of the station, certainly a more intense presence than in the last couple of years, during which I’ve visited perhaps half a dozen times.

I did in fact wonder what Bill would make of the place, compared to the sunny climes of God’s own country, and his response doesn’t surprise me.

As a long term resident in Brighton,I was at the talk,I can verify that

homelessness is indeed on the up although it has been here for at least 28 years.

Unemployment ,apart from a spike at the GFC is not significant,although of course

much employment is temporary and or part time.

Housing costs are londonish ,and the rise in homelessness is more a symptom of

this than unemployment,although of course once homeless employment opportunities

are limited.

As to the substance of the article I support any government policy which either

promotes greater fiscal stimulus or greater fiscal transfers.

A more progressive tax system including higher rates of taxes for the wealthy should

be a no brainer for progressives it was a vital part of the inclusive growth of the post

war settlement.

It’s the lack of hope in the eyes of others that is perhaps the biggest concern, with the homeless being the visible tip of the iceberg for the precariat. It is not hard to imagine that very many in terms of debt who have been banking on the arrival of what has turned out to be a non-existant recovery, are possible companions to those human illustrations of societal failure. I have seen Dublin over various visits over 20 years turn into a shadow of it’s once vibrant self, with exactly the same disease as is described for Brighton which could I imagine be applied to many other places – the roots of favellas ?

Homelessness is appalling.

High housing costs are to blame.

Unemployment is low.

Homeless people need to be put in social housing and

Social prograns to help build a life.

Unfortunately they are just abandoned.