I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The Bank of Japan needs to introduce Overt Monetary Financing next

The latest survey data from the Bank of Japan is interesting and supports a growing awareness among policy makers that monetary policy has run its course and will have to work more closely with active fiscal policy to stimulate economic growth. These insights have been a hallmark of ideas advanced for many years now by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents (including myself). The data shows that the negative interest rate and large-scale quantitative easing programs that the Bank of Japan has been pursuing have not had their desired effect. It was clear when they were announced that they would fail to achieve their goals. I wrote about that in 2009 and 2010. But it seems that the mainstream policy debate has to be dragged kicking and screaming through a series of policy failures before any progress is made towards actual solutions that will work. The Bank of Japan Board meets later this week and I am hoping they announce their intention to work closely with the Ministry of Finance (fiscal policy) to introduce Overt Monetary Financing (OMF) where the bank provides the monetary capacity to support much larger fiscal deficits with no further debt being issued to the non-government sector. That would finally put policy on track to do something effective and productive. It would also provide some policy leadership to guide other nations towards a more prosperous future (like Britain).

The mainstream macroeconomists teach their students that if the central bank expands bank reserves by buying financial assets from the non-government sector, the money supply will rise and inflation accelerates both because ‘too much money chases too few goods’ (the demand effect) and because inflationary expectations rise and build in self-reinforcing behaviour.

The theory is deeply flawed.

Please see the following blogs for background:

1. Money multiplier – missing feared dead.

2. Money multiplier and other myths.

3. Overt Monetary Financing – again.

4. OMF – paranoia for many but a solution for all.

5. Building bank reserves will not expand credit.

6. Building bank reserves is not inflationary.

Those blogs explain in considerable detail the nature of the mainstream theory and the reason it is both logically and empirically flawed.

However, the macroeconomics teaching programs have hardly altered in universities around the world despite the experience since the GFC that has categorically rejected:

1. The idea of the monetary multiplier (where central bank money is multiplied up into a larger money supply via the bank credit creation).

2. The idea that bank lending is reserve constrained (banks do not worry about reserves when creating loans and loans create deposits, not the other way around).

3. The assertion that expanding bank reserves are inflationary.

4. The assertion that expanding bank reserves drive inflationary expectations upwards.

And more.

Japan continues to provide an empirical macroeconomics laboratory which because it is a real world situation is a powerful antidote to the nonsense that appears in the mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and is peddled out in so-called DSGE models that are the standard playthings of New Keynesians and their ilk.

The theory and the DSGE models have offered nothing useful to help us understand the nature of the GFC, its causes, and its remedies.

These theories largely eschewed the use of fiscal policy (although some practitioners said temporary stimulus would be okay but would have to be unwound fairly quickly) and promoted the use of monetary policy as the primary counter-stabilisation measure.

They claimed that bank lending could be stimulated if central banks engaged in quantitative easing exercises – that is, buying financial assets from the banks in exchange for central bank cash.

Credit growth proved to be largely insensitive to the massive QE purchasing programs that the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, the ECB and the US Federal Reserve mounted.

MMT predicted that credit growth would remain weak as long as borrowers (both firms and households) were pessimistic about the future. And that pessimism was wrought by the rising unemployment and the weak sales growth.

And the non-government sector balance sheet was overburdened with debt after the pre-GFC credit binge. Consolidation rather more of the same was required.

Banks were not lending because they didn’t have sufficient reserves – they were not lending much because there were few borrowers.

The mainstream economists also claimed that if the central bank ran low interest rate regimes for long enough then the low cost of debt would stimulate credit growth.

The low interest rates happened but the credit growth didn’t (and hasn’t).

The mainstream economists were living on the knife edge though. They also claimed that the QE was dangerous because it would stimulate inflation.

And … you’ve got it … deflation set in.

All because of the complementary policies they promoted relating to fiscal austerity and so-called structural reforms (aka cutting worker’s wages and hence their capacity to spend).

And finally, those inflationary expectations would break out eventually and drive an inflationary episode which for some mainstream economists would quickly spill over into hyperinflation.

Do a Google search and see how many times Zimbabwe and Weimar were mentioned in financial commentaries since 2008. Lots is the answer!

So what about Japan?

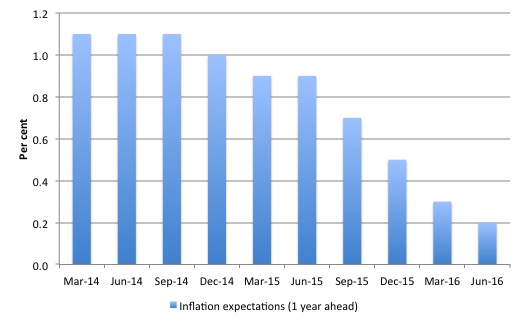

The most recent data is quite illustrative. The following graph shows the TANKAN Inflation Outlook of Enterprises (1 year ahead) from March 2014 to June 2016.

Having any trouble interpreting the trend?

Then relate that to the massive central bank asset purchases over the last several years.

It tells us that repeated attempts by the Bank of Japan to stimulate higher inflation (Haruhiko Kuroda’s so-called ‘shock and awe’ strategy) and break out of the deflationary spiral have not stirred up higher inflationary expectations.

In fact, exactly the opposite.

Further more detailed analysis of the “Inflation Outlook of Enterprises” data (as at June 2016, released July 4, 2016) shows that a much higher proportion of respondents think that inflation will remain as it is now – in one year, 3 years and 5 years ahead, compared to those who think it will edge up a bit.

No-one thinks inflation will accelerate any time soon in Japan if the survey results are anything to go by.

The Bank of Japan also published an interesting Working Paper in January 2016 (WP 16-E-1) – Inflation expectations and monetary policy under disagreements – which, among other things, studied:

… whether long-run inflation forecasts converge to the 2% target set by the Bank of Japan to achieve price stability … any dissonance among the central bank and agents can hinder attempts to end chronic deflation in Japan.

It also sought to determine:

whether a drastic change in the perception about a monetary policy regime is induced by QQE.

The central bank government Haruhiko Kuroda claimed in 2013 “that QQE is intended to drastically change the expectations of markets and economic entities.”

So has the massive QQE program introduced by the Bank of Japan caused expectations in the non-government sector to change.

According to mainstream theory the answer should be an emphatic yes.

The study finds that:

1. The “long-term forecasts” of inflation formed by the private sector in Japan “fail to converge to” the 2 per cent target inflation rate of the Bank of Japan.

2. “not only experts but also households disagree with the 2% level as the long-run inflation rate.”

3. And most significantly, ” the private sector’s perception about a monetary policy stance does not significantly differ before and after the introduction of the inflation target and QQE in 2013 … there is no upheaval in the agents’ perception about a monetary policy stance enough to induce a regime change.”

Later this week, the Bank of Japan Board meets and will decide what to do next. My advice is that they take heed of the data and its own research and abandon pushing interest rates further into negative territory.

They should also abandon any further QQE exercises – they are futile – in relation to pushing up the underlying inflation rate and stimulating the economy.

What they should do is to bring the monetary capacity of the Bank of Japan in line with the fiscal goals of the Ministry of Finance and engage in some ‘overt monetary financing’ (OMF).

I wrote about OMF in detail in my current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale.

Essentially, from an MMT perspective, OMF is a desirable option that allows the currency issuer to maximise its impact on the economy in the most effective manner possible.

While some economists call it ‘printing money’ (even Abba Lerner used that terminology), the idea of OMF is very simple and does not actually involve any printing presses at all.

While the exact institutional detail can vary from nation to nation, governments typically spend by drawing on a bank account they have with the central bank.

An instruction is sent to the central bank from the treasury to transfer some funds out of this account into an account in the private sector, which is held by the recipient of the spending.

A similar operation might occur when a government cheque is posted to a private citizen who then deposits the cheque with their bank.

That bank seeks the funds from the central bank, which writes down the government’s account, and the private bank writes up the private citizen’s account.

All these transactions are done electronically through computer systems. So government spending can really be simplified down to typing in numbers to various accounts in the banking system.

When economists talk of ‘printing money’ they are referring to the process whereby the central bank adds some numbers to the treasury’s bank account to match its spending plans and in return is given treasury bonds to an equivalent value.

That is where the term ‘debt monetisation’ comes from.

Instead of selling debt to the private sector, the treasury simply sells it to the central bank, which then creates new funds in return.

This accounting smokescreen is, of course, unnecessary.

The central bank doesn’t need the offsetting asset (government debt) given that it creates the currency ‘out of thin air’.

So the swapping of public debt for account credits is just an accounting convention.

OMF supports fiscal expansion, which directly stimulates the economy by putting extra dollars of spending into the economy.

A reliance on monetary policy to resolve the crisis will fail, especially when fiscal policy is forced by the austerity mania to act in a pro-cyclical fashion.

We now have 8 or so years of experience with that sort of failure.

The correct policy response in circumstances of low or falling inflation and massive spending shortages is to pair the monetary capacity with the fiscal stimulus.

The QE and QQE interventions and similar policies are not effective because they have been conducted independently of any fiscal stance.

In other words, the imposition of fiscal austerity kills any growth potential that these monetary policies might have.

In a coherent policy world, monetary policy works has to work in tandem with fiscal policy (deficit expansion) to increase spending rather than to push up private borrowing and debt.

From the MMT perspective, the preferred approach is to eliminate any of the voluntary constraints on central banks so they can directly underwrite the fiscal deficits without the need for governments to engage in primary issuance of debt to the private markets.

It is clear – and has been for some years – that the main problem holding economic growth back is a chronic deficiency of aggregate spending.

It is also clear that the non-government sector is not going to go back to the days of wild credit growth and ever-increasing debt levels.

Cue stage left: the only other sector left that can redress the deficiency is the government sector.

The world needs significantly larger fiscal deficits – in some cases several percentage points of GDP larger.

The best thing the Bank of Japan can do is to lead the way and once again demonstrate the folly of mainstream economics.

It can do that by announcing a massive OMF strategy in tandem with the Ministry of Finance. Then things would start moving in the direction they desire and, perhaps, the rest of the world would take one step further in the direction of abandoning the insipid and dangerous neo-liberal mainstream macroeconomics (including New Keynesian ideas).

A problem that might prevent Prime Minister Abe and the Bank of Japan governor taking this step on the ‘wild side’ is that long-term Japanese government bond yields (out to 15 years) are negative and the 40-year bonds are at extremely low levels.

This might induce the Japanese government to issue more debt to the private bond markets to ‘finance’ a large-scale spending program.

The preferred approach is to stop issuing JGBs and just spend with the backing of the Bank of Japan (that is, OMF).

This discussion is also in line with broader sentiment on the need for more fiscal action.

The IMF are now increasingly pushing for fiscal stimulus and concluding that monetary policy has run its course.

At the recent G-20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meetings in China (July 23-24), the IMF wrote in its briefing document that:

1. “Global growth remains weak and fragile, and “Brexit” marks the materialization of an important downside risk for the world economy.”

2. “Strong global growth will not return without decisive policy action.”

3. “Even before the “Brexit” shock, global growth had been lackluster … the level of underlying growth remained weak, and inflation-now projected at just 0.2 percent in 2016-was still uncomfortably low.” Which means that growth was already deteriorating so don’t blame Brexit!

4. While financial markets (over) reacted to the Brexit vote “Since then, markets have stabilized and broad equity measures have recovered.” And … Britain is much more competitive in international markets than it was before as a result of the sterling drop.

5. “The fact that income is not only growing more slowly but is also shared less equally creates additional challenge … the share of produced income that accrues to workers has been on a declining trend in many advanced and emerging economies.” This, in turn, undermines the capacity of economies to introduce “necessary structural reforms”.

6. “To lift growth and counter risks, G-20 policymakers will need to follow a broad-based approach that simultaneously provides better-balanced demand support where needed, addresses private sector balance sheet issues, and implements structural reforms.”

Which means – increasing fiscal deficits will be required to provide the necessary stimulus to spending and provide the means for private sector debt reduction to occur (the “private sector balance sheet issues”).

Remember, a fundamental insight of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is that the government deficit (surplus) is exactly equal to the non-government surplus (deficit) at all times.

If you still do not quite grasp that national accounting reality then please review the following introductory suite of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for basic Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) concepts.

What it means is that if the non-government sector is to rein in its excessive debt levels and get itself back into a position where it lifts consumption and investment spending to support growth with less government support, then it has to run surpluses.

That means the government sector has to keep running deficits – and the process of balance sheet consolidation for the non-government sector is not fast. It will take a decade or more yet.

Please read my blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more discussion on this point.

In this context, the IMF write that:

Where monetary policy space is narrowing and there is fiscal space, fiscal policy can help support demand and close output gaps-including through measures that will strengthen growth also in the medium and long term (e.g., Canada, Korea) or, where necessary, facilitate balance sheet repair. In most countries, it will be important to adjust expenditure priorities to finance reforms that increase potential output (e.g., Germany). For the euro area, the use of centralized investment funds to support infrastructure investment in countries without fiscal space would be appropriate. A coordinated use of fiscal space would be beneficial should the global outlook weaken materially.

Now, once we get over the IMF’s obsession with the concept of fiscal space, which they define in terms of some amorphous, yet to be found, deficit or debt threshold, what this means is clear.

Governments with output gaps have to lift net spending to fill the spending gap left by the on-going cautious behaviour of the non-government sector, which remains saddled with excessive debt levels and pessimistic outlooks given the persistent and elevated levels of private debt.

Britain could lead the way and demonstrate that the Brexit vote is not a vote for an inevitable recession. While some of the sentiment appears negative at present, the national government could easily announce a large-scale public investment and employment intervention which would see growth increase and private sentiment quickly reverse.

There are those in government and beyond who are wishing for a recession right now in Britain to show those racist, ignorant nobodies from outside London – in a sort of ‘I told you so’ moment – just which little box they should crawl back into!

I wrote about fiscal space and the IMF in this blog (among others) – The ‘fiscal space’ charade – IMF becomes Moody’s advertising agency.

Moreoever, in a recent IMF Working Paper (16/138) – The Fiscal Multiplier in Small Open Economy : The Role of Liquidity Frictions (published July 12, 2016), we learn that fiscal stimulus is likely to be very expansionary, especially if nation states impose capital controls (or other “frictions in international capital markets”).

The research, which I will comment on in more detail in another blog, concluded that “conventional theory” (that is, mainstream economics) wrongly predict that fiscal multipliers (the extra dollars of GDP per dollar of extra government spending) are below one.

A fiscal multiplier below one means that if governments spend an extra $1, GDP rises by less than a $1 because it ‘crowds out’ private spending.

This is the classic argument against the use of fiscal deficits.

The IMF paper concludes that “the long-term scal multiplier in the small open economy is as large as 1.6 if international capital mobility is imperfect”.

That means that if governments spend an extra $1, GDP rises around $1.60.

The paper believes this to arise from the new debt accompanying deficit spending, which “results in more liquidity in the private-sector wealth, allowing entrepreneurs to increase their investment in physical capital.”

I will examine the arguments in detail another time.

Conclusion

Sooner rather than later, the Bank of Japan is going to abandon its negative interest rate and QQE strategy because the evidence is clear – it doesn’t work.

The next cab off the rank will be OMF. It will demonstrate categorically that fiscal stimulus supported by monetary expansion is the most direct and effective way to get out of a deficient demand malaise.

We will see what they come up with after their Board meeting later this week.

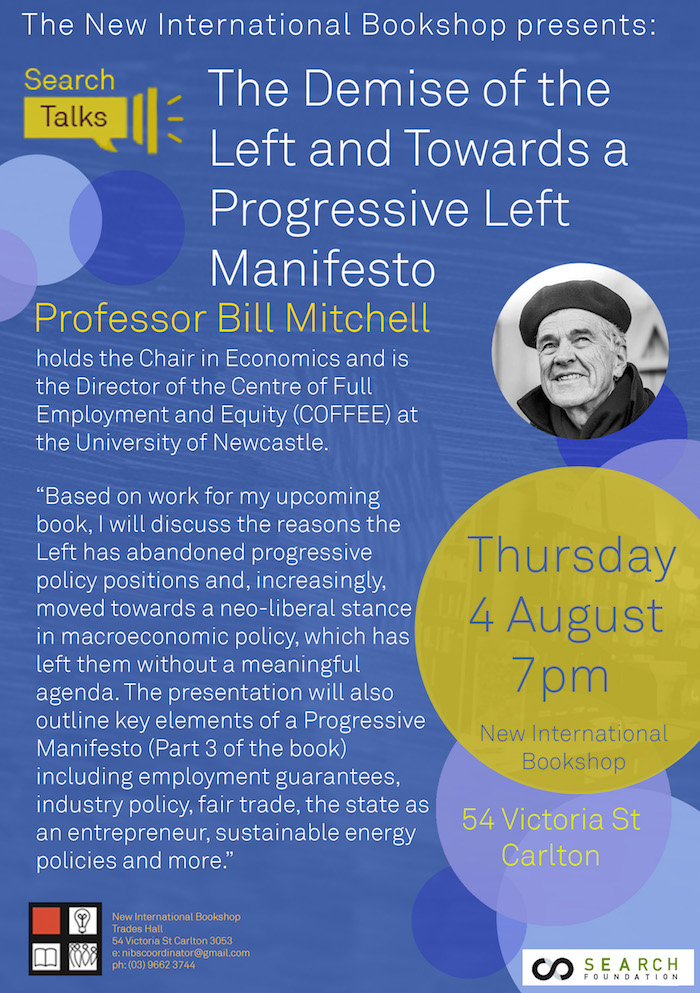

Upcoming talk at the New International Bookshop in Melbourne – August 4, 2016

On August 4, 2016, I will be giving a talk at the New International Bookshop in Melbourne (Australia) on the topic – The demise of the Left and towards a Progressive Left Manifesto – which is the topic covered in my latest book project that is nearing completion.

The talk will run between 19:00 and 20:30 and the venue is at 54 Victoria St, Melbourne, Australia 3053 – which is part of the Victorian Trades Hall.

The actual room will now be the Bella Union bar (upstairs from the Bookshop) and drinks will be available there.

There is a Facebook Page for the event.

The Bookshop is staffed by volunteers who appreciate any support they can get.

I spent many hours in my youth sifting through all sorts of radical books in its previous incarnation as the International Bookshop (operated by the now defunct Communist Party of Australia) in Elizabeth Street, Melbourne.

When I was a university student without much cash at all one – great staff member – there used to give me an orange on a regular basis – she always had one available and I guess she knew I haunted the place.

Here is the flyer. It would be great to see people at the event and the small entry fee goes to helping sustain the Bookshop, which has a long history in providing alternative and radical literature to Australian readers.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Or just offer an unlimited overdraft and quit issuing bonds at all.

Bill, What do you think is the current Output gap in, say, Australia – and the USA?

I did see a report that back in 2012, someone called Christy Romer – chief White House economist? – worked out that the US output gap was between $1.7Trillion and $1.8 Trillion. Apparently “our good friend” Larry Summers wouldn’t put it to Obama in the report he saw. You could pay a lot of medicare and education and welfare with that money.

This technique, I would think, can help private banking. The companies who win infrastructure bids will open accounts at local banks. The money quickly enters the local business community which, in turn, increases demand for product and services which, in turn, allows the local banks to make new loans and thus gain assets. Alternatively, the government could allow the local banks to record the infrastructure loan on their books. Thus creating an asset immediately. What’s not to like? Yet private banks fight this government activity. To me this is a mystery. It must be political ideology that interferes–in what any normal person would consider a ‘no brainer.’

Spock, banks of the 21st century have a prime directive of their own: “Keep population in debt. Do not allow population out of debt.” As visitors to this planet, do we violate our prime directive and save the population?

hey chris,

you regularly see business leaders and lobby groups in this country arguing for quicker and bigger surpluses, without thinking through the accounting logic , that its actually a bad idea for them.

they all rabbit on about the government debt, when the real elephant in the room is the banking system debt. they don’t make the connection between the cash flow and balance sheet improvements in the private sector and larger government deficits.

“The research, which I will comment on in more detail in another blog, concluded that “conventional theory” (that is, mainstream economics) wrongly predict that fiscal multipliers (the extra dollars of GDP per dollar of extra government spending) are below one.

A fiscal multiplier below one means that if governments spend an extra $1, GDP rises by less than a $1 because it ‘crowds out’ private spending.

This is the classic argument against the use of fiscal deficits.

The IMF paper concludes that “the long-term scal multiplier in the small open economy is as large as 1.6 if international capital mobility is imperfect”.

That means that if governments spend an extra $1, GDP rises around $1.60.”

a government financial deficit can also be collatoralised and leveraged eventually. how can the fiscal multiplyer be less than 1

The crazy thing with negative interest rates is they’re taxing their own citizens savings mad it’s deflationary! The exact opposite of their goal of getting inflation. It’s removing yen from the private sector. It’s madness.

Richard Koo thinks this wouldn’t work, because everyone would suddenly think like a macro-economist: http://ftalphaville.ft.com/2016/07/27/2170980/koo-on-why-helicopter-money-just-wont-work

That article assumes that the quantitative theory of money holds true and believes in ‘money multiplier’. Junk.

Dear Bill,

Congratulations, indeed.

That was a broad and deep Rubicon indeed that you just crossed, and I appreciate the true (Lernerian) Post-Keynesian observations here about the great economic potential associated with Overt Money Financing (OMF), Turner’s design for what we reformers simply call ‘public money administration of our national economy.

You have it just about right here, and, as you mentioned, its application may look different depending on the host monetary-economic environment.

But I do see the same problem that I have with Adair Turner’s attempt, it being that this effort is central-bank-centric, and not really fiscally derived at all, knowing as I do that MMTers consider the central bank, for some yet unexplained reason, to be part of the government.

Not one bit in the USA.

Rather, the full decision should be governmental (monetary authority with regard to size, and legislative with regard to ultimate spending) and the CB becomes merely a fiscal agent pass through, BECAUSE the seigniorage gain is authorized in the budget process ….. so its IN the TGA.

So, get that part straight, and we’ll be talking the same language.

Public money.

Because they are ALL “our” sovereign money systems.

Thanks for your work, Bill. Economic democracy will be ours.

Still listening – “Just a Case of Different Values”.

joe bongiovanni

The Kettle Pond Institute

Joe,

Regarding the technocratic solution to controlling the money supply, what techniques can be relied on to predict the money needed to support full production commerce? If there are such techniques, why can they not be used in an open source manner to hold a profligate democratic arm to account? How can high priests help the matter here?

Brendanm, measuring the output gap and a proper measure of inflation is what is needed. Then you can maximise fiscal expansion to meat the maximum output. But is very important that while the government is supportive of full employment, is also supportive of reducing extractive economic activities that add up ineficientes (ie. overbloated FIRE sector) and indirectly, inflation, as well as tax up that consumption that hurts the majority indirectly throught inflation (some luxury goods) or unsustainable industrial activity (ie. fracking and oil-based economy overall). The governments always picks up winners, the key is for the government to pick good winners, instead of bad winners, as it usually does through collusion nowadays in oligarchic ‘democracies’ over the developed world.

Better governance would be needed to reduce dependency on global trade (looking after trade balances) as they build up instability on the long run too (a lot of MMT’ers prefer to ignore this part, ‘imports are a benefit, exports a cost’; but the political reality is what it is).

Acknowledging MMT is just an initial steep in the right direction, and a small but important one.

the national government could easily announce a large-scale public investment and employment intervention which would see growth increase and private sentiment quickly reverse. Bill Mitchell

The proper abolition of government-provided deposit insurance should require enormous amounts of new fiat to be created and equally distributed to all citizens to finance the transfer of at least some currently insured deposits held with commercial banks, credit unions, etc. to inherently risk-free accounts at the central bank itself.

Government privileges for private credit creation are a root cause of unjust wealth inequality so how about we eliminate those?

nstead of selling debt to the private sector, the treasury simply sells it to the central bank, which then creates new funds in return.

This accounting smokescreen is, of course, unnecessary.

The central bank doesn’t need the offsetting asset (government debt) given that it creates the currency ‘out of thin air’.

So the swapping of public debt for account credits is just an accounting convention. Bill

Well, having assets to sell gives the central bank credibility wrt fighting inflation so they are useful.

Otoh, interest paying sovereign debt is, as you have said Bill, “corporate welfare.”

So what’s the solution? How about negative rates for the most liquid sovereign debt, central bank liabilities, aka “reserves”, with less negative rates for sovereign debt with longer maturities with the longest maturity sovereign debt (e.g. 30 year Treasury Bonds) paying 0%?

That leaves the problem of physical cash as a means to escape the negative rates but the solution to that would include the allowance of individual citizen accounts at the central bank with, say, the first $250,000 exempt from negative interest. Then the problem is reduced to larger cash hoarders, at least, for which other measures might be used such the central bank selling physical cash at a premium and buying it back at a discount.

Andrew banks in Germany are apparently already building vaults to store physical cash to avoid negative rates. That’s apparently one of the reasons they abolished the 500 euro not to make this harder. Instead of negative rates why not just use taxes to remove excess money.

Instead of negative rates why not just use taxes to remove excess money. aa

If there’s excess fiat, isn’t it because only banks may use it? Except for inconvenient, unsafe physical fiat, aka “cash”?

So why not allow all citizens to use fiat in the form of inherently risk-free, convenient accounts at the central bank itself? And abolish government provided deposit insurance and all other privileges for the banks?

Oh, pardon me please, Jason H. I mis-attributed a quote from you to me.

Reply to : Brendanm says:

Friday, July 29, 2016 at 15:15

Very sorry for the delay.

I do believe that IDG gave the proper answer, being the GDP-potential gap.

Whatever that is deals with the new money quantity issue. (rounded up to the nearest $hundred billion or so)

When the government absorbs that level of seigniorage gain into its budget income, it can identify its total spending program to ensure that all of that results in demand enhancement. And that public budget spending ensures a zero monetary-inflation impact, like all government spending should.

There’s no magic.

But its a vast improvement over the present wealth-concentrating booms and busts associated with banker-issued debt money.

Thanks.

Reply to : Andrew Anderson says:

Saturday, July 30, 2016 at 17:01

“So why not allow all citizens to use fiat in the form of inherently risk-free, convenient accounts at the central bank itself? And abolish government provided deposit insurance and all other privileges for the banks?”

If the government is issuing all money (being ‘real’ and ‘permanent’ in nature), then certainly private bank deposit-insurance could be eliminated. Although, being that Guv is then responsible for managing the money and credit aggregates, they SHOULD guarantee the sanctity of those deposits … just as a confidence-building measure.

Under this scenarion, ndeed, the banks would need a sharpr pencil.

they SHOULD guarantee the sanctity of those deposits … just as a confidence-building measure. joe bongiovanni

Accounts at the central bank are inherently risk-free so then the question is to whom and at what point shall negative interest apply to discourage risk-free money hoarding? And how is cheating to be precluded, e.g. via multiple accounts?

I suggest one negative interest-free account per adult citizen to a limit of, say, $250,000 US. All other accounts at the central bank to be subjected to negative interest from $0.

As for depository institutions, let them create all the liabilities they dare but as 100% private businesses with 100% voluntary depositors.

Under this scenarion, ndeed, the banks would need a sharpr pencil. joe bongiovanni

If you’re implying that private credit creation would suffer then please note that the proper abolition of government-provided deposit insurance should require the equal distribution of huge amounts of new fiat to all citizens to finance the transfer of at least some currently insured accounts at banks to inherently risk-free accounts at the central bank itself.

Thus greatly reducing the need to borrow in the first place.

The BoJ could issue “Land Receipts”, known as LRs. This is not to be confused with Credit Receipts, which are an actual monetary instrument to represent debt.

A Land Receipt, in contrast to a Credit Receipt, is a fictional entity that allows Yen and the land mass of Japan to be reconciled. How can an LR be sold to foreigners in exchange for foreign capital, whereas the foreigner will take deed to the land and the Japanese person will take the cash and vacate the island?