Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Australian Labour Force – improvement but credibility stretched

Today’s release of the – Labour Force data – for November 2015 by the Australian Bureau of Statistics once again brings into question the validity of drawing assessments about the state of the labour market on the basis of monthly changes in the data. Today’s release shows that employment increased by 71,400 (0.6 per cent) on the back of a similar substantial increase last month. The estimates strain credibility although they are not necessarily at odds with what other data is suggesting. The direction is probably correct – that is, the labour market has improved (the Employment-Population ratio reliably indicates that). The ABS estimated that despite the dramatic increase in employment, unemployment fell by only 2,800 as a result of a 0.3 percentage points surge in the participation rate (again stretching credibility). Perhaps a signal on how volatile the data is, the ABS estimated the teenage participation rate rose by 0.7 percentage points on theh back of a estimated 0.8 point rise in October – again rather fanciful. The cautious position is to look at the trend over the last several months and that suggests that the labour market has improved. However, the teenage labour market remains very week with no discernible upwards trend revealing itself yet. If the forecasted decline in private investment occurs over the next 12 months, then this improvement in the labour market data will not persist.

The summary ABS Labour Force (seasonally adjusted) estimates for November 2015 are:

- Employment increased 71,400 (0.6 per cent) with full-time employment increasing by 41,600 and part-time employment rising by 29,700.

- Unemployment decreased by 2,800 to 739,100.

- The official unemployment rate decreased by 0.1 percentage points to 5.8 per cent.

- The participation rate increased 0.3 percentage points to 65.3 per cent – the second consecutive monthly decline. It is still well below its November 2010 peak (recent) of 65.9 per cent.

- Aggregate monthly hours worked decreased 12.7 million hours (0.8 per cent).

- The quarterly ABS broad labour underutilisation estimates (the sum of unemployment and underemployment) were updated for this quarter. Underemployment was at 8.4 per cent and total labour underutilisation rate was at 14.3 per cent. There were 1,051.2 thousand persons underemployed and a total of 1.839.3 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed. The next quarterly release will be in the February 2016 publication.

Employment growth – another dramatic surge yet total working hours falls

In the last month, total employment increased by 71,400 (0.6 per cent) with full-time employment increasing by 41,600 and part-time employment rising by 29,700.

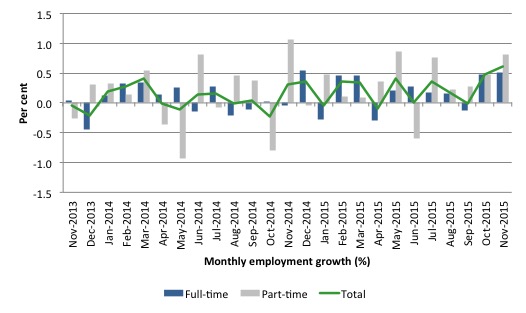

This is the second month of dramatic employment improvement on the sort of results we have seen in the past 18 months and remains hard to fathom, especially as I note below, that monthly hours of work continue to fall.

Over the last 24 months or so we have seen the labour market data switching back and forth regularly between negative employment growth and positive growth spikes.

The last two months performance appears to break that mould. We will see if it persists.

The following graph shows the month by month growth in full-time (blue columns), part-time (grey columns) and total employment (green line) for the 24 months to November 2015 using seasonally adjusted data. It gives you a good impression of just how flat employment growth has been notwithstanding the huge spike in part-time employment in the November 2014 survey and also how relatively strong the last two months have been.

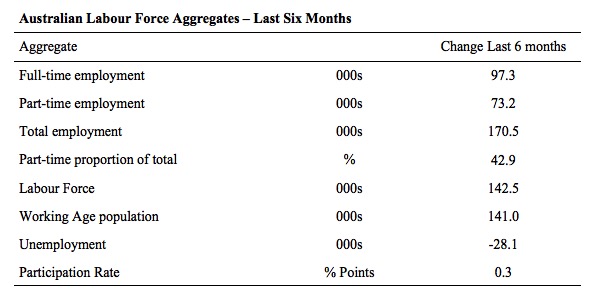

The following table provides an accounting summary of the labour market performance over the last six months. The monthly data is highly variable so this Table provides a longer view which allows for a better assessment of the trends. WAP is working age population (above 15 year olds).

The conclusion – overall there have been 190 thousand jobs (net) added in Australia over the last six months while the labour force has increased by 189.5 thousand. Employment growth has thus just outstripped the increase in the supply of labour.

Full-time employment has risen by 118.6 thousand jobs (net) while part-time work has risen by 71.4 thousand jobs. Thus, 37.6 per cent of the total employment created (net) over the last 6 months has been part-time.

The participation rate has risen by a substantial 0.5 points from very low levels.

Unemployment has fallen by 0.5 thousand as a result of employment growth being just in excess of what has been required to match the labour force increases.

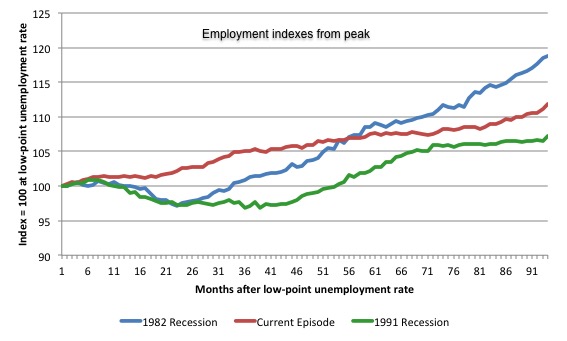

The following graph shows employment indexes for the last 3 recessions and allows us to see how the trajectory of total employment after each peak prior to the three major recessions in recent history: 1982, 1991 and 2009 (the latter to capture the current episode).

The peak is defined as the month of the low-point unemployment rate in the relevant cycle and total employment was indexed at 100 in each case and then indexed to that base for each of the months as the recession unfolded.

I have plotted the 3 episodes for 93 months after the low-point unemployment rate was reached in each cycle – the length of the current cycle.

The initial employment decline was similar for the 1982 and 1991 recessions but the 1991 recovery was delayed by many months and the return to growth much slower than the 1982 recession.

The current episode is distinguished by the lack of a major slump in total employment, which reflects the success of the large fiscal stimulus in 2008 and 2009.

However, the recovery spawned by the stimulus clearly dissipated once the fiscal position was reversed and the economy fell back into producing very subdued employment outcomes. The last several months have showed some signs that the pace of employment growth is picking up.

Moreover, since February 2008, employment has grown by a miserly 11.8 per cent, which is a very slow pace in historical terms for such a long period.

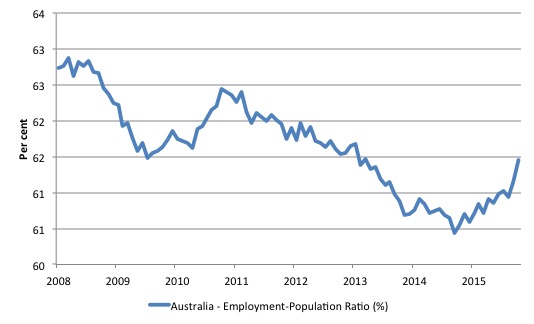

Given the variation in the labour force estimates, it is sometimes useful to examine the Employment-to-Population ratio (%) because the underlying population estimates (denominator) are less cyclical and subject to variation than the labour force estimates. This is an alternative measure of the robustness of activity to the unemployment rate, which is sensitive to those labour force swings.

The following graph shows the Employment-to-Population ratio, since February 2008 (the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle).

It dived with the onset of the GFC, recovered under the boost provided by the fiscal stimulus packages but then went backwards again as the last Federal government imposed fiscal austerity in a hare-brained attempt at achieving a fiscal surplus.

The ratio has been steadily rising since October 2014 which would suggest that the labour market may have bottomed out and will improve slowly as long as there are no major policy contractions or cuts in private capital formation.

The on-going fiscal deficit is still supporting growth in the economy as the spending associated with the mining boom disappears.

The series increased sharply by 0.3 points in each of the last two months, which are relatively substantial jumps in terms of recent history but not so if we examine the whole series dating back to February 1978..

Teenage labour market – gains and losses

The teenage labour market again showed mixed outcomes with full-time employment falling by 4 thousand and part-time employment rising by 15 thousand (perhaps a sign that the gift buying season is in full swing now and retail is a major employer of this cohort).

Again, I have serious doubts about the veracity of this data. Last month, the ABS reported that the teenage participation rate for 15-19 years jumped by 0.8 percentage points. In November 2015, the estimates show a further jump of 0.5 percentage points. These are very large change in historical terms and difficult to believe.

The teenage unemployment rate fell from 17.9 per cent to 17.7 per cent in November 2015 on the back of the part-time employment growth.

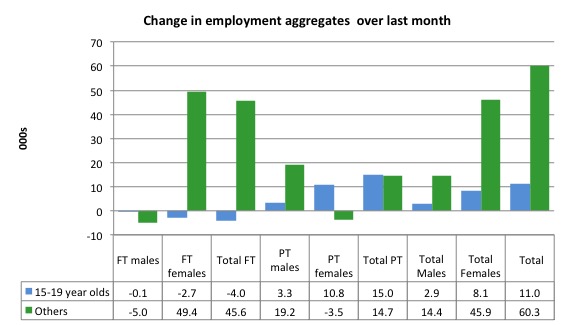

The following graph shows the distribution of net employment creation in the last month by full-time/part-time status and age/gender category (15-19 year olds and the rest)

If you take a longer view you see how poor the situation remains.

Over the last 12 months, teenagers have gained 12.2 thousand jobs overall while the rest of the labour force have gained 332 thousand net jobs. Remember that the overall result represents a fairly poor annual growth in employment.

11 rhousand of those 12.2 thousand jobs were all added in the last month.

The teenage segment of the labour market is being particularly dragged down by the sluggish employment growth, which is hardly surprising given that the least experienced and/or most disadvantaged (those with disabilities etc) are rationed to the back of the queue by the employers.

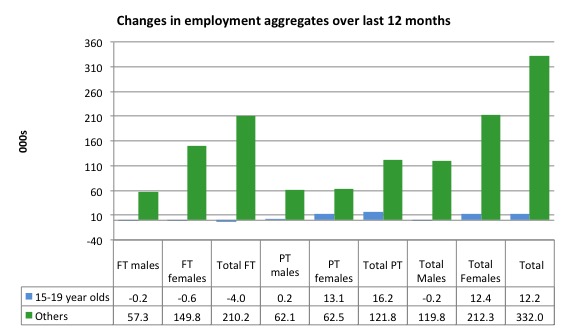

The following graph shows the change in aggregates over the last 12 months. It is as if the teenagers have not had a stake in the labour market either way (blue bars barely visible)

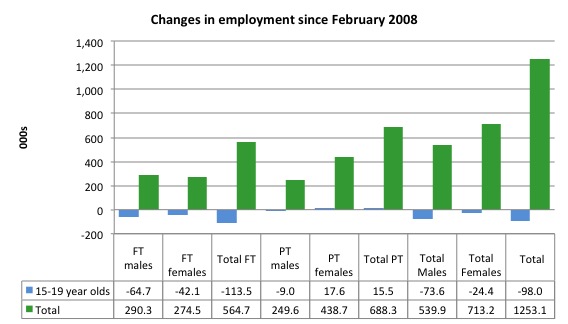

To further emphasise the plight of our teenagers, I compiled the following graph that extends the time period from the February 2008, which was the month when the unemployment rate was at its low point in the last cycle, to the present month (November 2015). So it includes the period of downturn and then the so-called “recovery” period. Note the change in vertical scale compared to the previous two graphs.

Since February 2008, there have been only 1,153.1 thousand (net) jobs added to the Australian economy but teenagers have lost a staggering 98 thousand over the same period. It is even more stark when you consider that 113.5 thousand full-time teenager jobs have been lost in net terms.

Even in the traditionally, concentrated teenage segment – part-time employment, teenagers have gained only 15.5 thousand jobs (net) even though 688.3 thousand part-time jobs have been added overall.

Overall, the total employment increase is modest. Further, around 54.9 per cent of the total (net) jobs added since February 2008 have been part-time, which raises questions about the quality of work that is being generated overall.

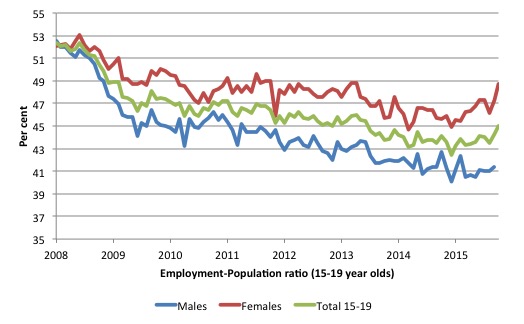

To put the teenage employment situation in a scale context the following graph shows the Employment-Population ratios for males, females and total 15-19 year olds since February 2008 (the month which coincided with the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle).

You can interpret this graph as depicting the loss of employment relative to the underlying population of each cohort. We would expect (at least) that this ratio should be constant if not rising somewhat (depending on school participation rates).

The facts are that the absolute loss of jobs reported above is depicting a disastrous situation for our teenagers. Males, in particular, have lost out severely as a result of the economy being deliberately stifled by austerity policy positions.

In the last month, with the employment situation improving, there has been some reversal in the downward trends in these ratios.

The male ratio has fallen by 11 percentage points since February 2008, the female ratio by 3.5 percentage points and the overall teenage employment-population ratio has fallen by 7.3 percentage points. That is a substantial decline in the employment market for Australian teenagers.

The other staggering statistic relating to the teenage labour market is the decline in the participation rate since the beginning of 2008 when it peaked in January at 61.4 per cent. In November 2015, the participation rate was just 57 per cent, although that was 0.7 percentage points up on the October 2015 data.

That is an additional 97 thousand teenagers who have dropped out of the labour force as a result of the weak conditions since the crisis.

If we added them back into the labour force the teenage unemployment rate would be 26.8 per cent rather than the official estimate for November 2015 of 17.7 per cent. Some may have decided to return to full-time education and abandoned their plans to work. But the data suggests the official unemployment rate is significantly understating the actual situation that teenagers face in the Australian labour market.

Overall, the performance of the teenage labour market remains poor. It doesn’t rate much priority in the policy debate, which is surprising given that this is our future workforce in an ageing population. Future productivity growth will determine whether the ageing population enjoys a higher standard of living than now or goes backwards.

I continue to recommend that the Australian government immediately announce a major public sector job creation program aimed at employing all the unemployed 15-19 year olds, who are not in full-time education or a credible apprenticeship program.

Unemployment – decreased 2,800 thousand

The unemployment rate fell by 0.1 percentage points to 5.8 per cent in November 2015.

Overall, the labour market still has significant excess capacity available in most areas and what growth there is is not making any major inroads into the idle pools of labour.

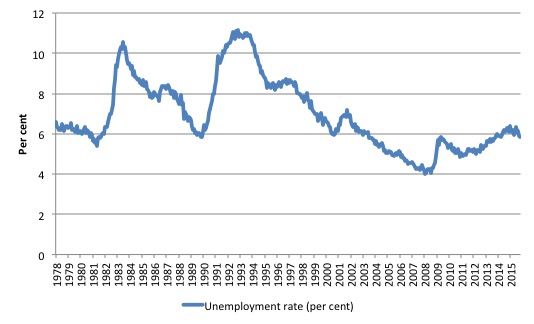

The following graph shows the national unemployment rate from February 1978 to November 2015. The longer time-series helps frame some perspective to what is happening at present.

After falling steadily as the fiscal stimulus pushed growth along, the unemployment rate slowly trended up for some months.

It is now above the peak that was reached just before the introduction of the fiscal stimulus. In other words, the gains that emerged in the recovery as a result of the fiscal stimulus in 2009-10 have now been lost.

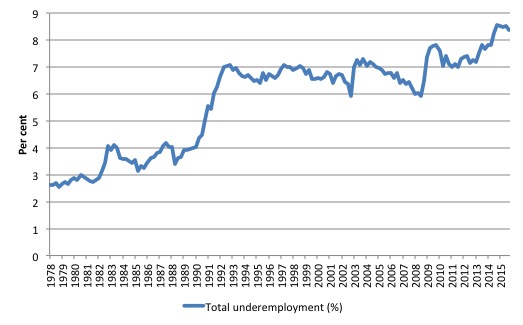

Broad labour underutilisation – upwards of 14.3 per cent

The ABS published its quarterly broad labour underutilisation measures for the November-quarter in this month’s data release.

In the November-quarter, total underemployment remained at 8.4 per cent and the ABS broad labour underutilisation rate (the sum of unemployment and underemployment) was 14.3 per cent.

| There were 1,058.4 thousand persons underemployed and a total of 1,797.5 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed. |

The following graph plots the history of underemployment in Australia since February 1978 to the November-quarter 2015.

If hidden unemployment is added to the broad ABS figure the best-case (conservative) scenario would see a underutilisation rate well above 16 per cent at present. Please read my blog – Australian labour underutilisation rate is at least 13.4 per cent – for more discussion on this point.

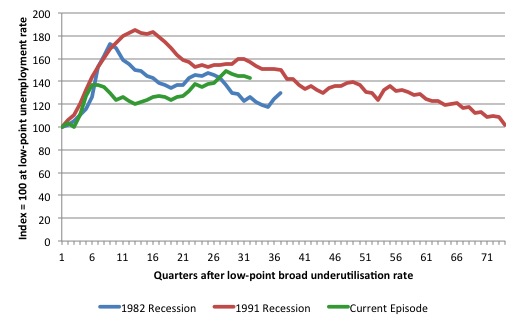

The following graph shows the ABS broad labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) indexes for the last three major recessions. The indexes start at 100 when the low-point is reached in each cycle and then indexed relative to that point as the downturn in recovery unfolds. It also is in terms of quarters rather than months.

We also show the full evolution of the the 1982 and 1991 episodes from the low-point (= 100) through the peak and back to the next low-point.

In the case of the 1982 recession the index had risen to a peak of 172.8 in May 1983 (a broad underutilisation rate of 14.5 per cent) and then fell back to 9.8 per cent by November 1989 (index value 117.5).

At that point, the cycle turned down again signalling the beginning of the 1991 recession. That cycle reached a peak of 185.4 (or 18.2 per cent in November 1992) and it took until February 2008 for it to reach the low-point of 10 percent (an index value of 101.4). That point marked the beginning of the next cycle.

That should tell you how severe the 1991 recession was and how asymmetric the labour market response is on either side of the cycle. From its start in November 1989 it took 74 quarters (18.5 years) to return to more or less that level.

In terms of the three recession comparison, at the same period in the ‘recovery’ (using quarterly data), the broad labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) had an index value of 126.6 in the 1982 recession (absolute value of 10.6 per cent); an index value of 157.3 in the 1991 recession (absolute value of 14.8 per cent); and an index value of 143.1 in the current period (absolute value of 14.3 per cent).

So while the level of unemployment is much lower now than in the 1982 and 1991 recessions (at a comparable stage), underemployment is now much higher and so the total labour underutilisation rates is higher. Further, the 1982 recovery in broad underutilisation terms was more robust than the current stagnating situation.

The current situation is akin to the devastating 1991 recession, although underemployment is higher and unemployment lower.

Commentators rarely see it in these terms. Joblessness is probably worse than underemployment but both mean that labour is wasted and income earning opportunities are being foregone. For a worker with extensive nominal commitments, the loss of income when hours are rationed may be no less severe than the loss of hours involved in unemployment, if the threshold of solvency is breached.

The next update will be for the February-quarter 2016 and will be published published in the March 2016 Labour Force release.

Aggregate participation rate – rise by 0.3 points

The November 2015 participation rate rose by a sudden 0.3 points to 65.3 per cent. Even so, it remains substantially down on the most recent peak in November 2010 of 65.9 per cent when the labour market was still recovering courtesy of the fiscal stimulus.

The fall in the official unemployment rate by 0.1 points this month would have been much larger had not the participation rate risk by so much.

The labour force is a subset of the working-age population (those above 15 years old). The proportion of the working-age population that constitutes the labour force is called the labour force participation rate. Thus changes in the labour force can impact on the official unemployment rate, and, as a result, movements in the latter need to be interpreted carefully. A rising unemployment rate may not indicate a recessing economy.

The labour force can expand as a result of general population growth and/or increases in the labour force participation rates.

What would have the unemployment rate been had the participation rate not risen by 0.3 points?

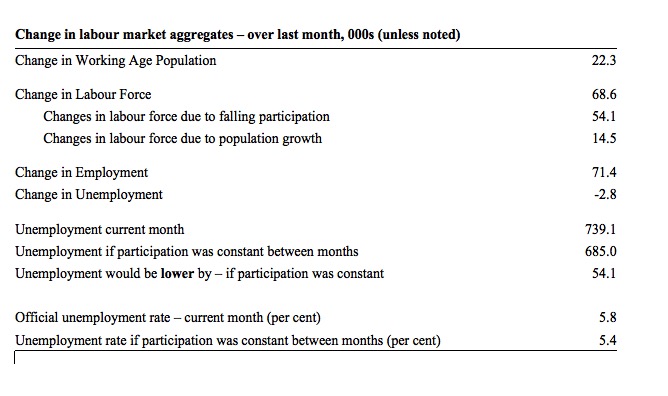

The following Table shows the breakdown in the changes to the main aggregates (Labour Force, Employment and Unemployment) and the impact of the rise in the participation rate.

In November 2015, the increase in employment of 71.4 thousand (net) jobs was accompanied by a labour force rise of 68.6 thousand. As a result, unemployment decreased by 2.8 thousand.

The rising labour force in November 2105 was the outcome of two separate factors:

- The underlying population growth added 14.5 thousand persons to the labour force. The population growth impact on the labour force aggregate is relatively steady from month to month but has slowed in recent months; and

- The rise in the participation rate meant that there were 54.1 thousand extra workers entering the labour force (relative to what would have occurred had the participation rate remained unchanged).

- The net result was the substantial rise in the labour force of 68.6 thousand.

If the participation rate had not have risen, total unemployment, at the current employment level, would have been 685 thousand rather than the official count of 739.1 thousand as recorded by the ABS – a difference of 54.1 thousand workers (the ‘participation effect’).

Thus, without the rise in the participation rate, the unemployment rate would have been 5.4 per cent (rounded) rather than its current value of 5.8 per cent.

The conclusion is that hidden unemployment fell in November 2105 while official unemployment rate fell by 0.1 points.

There is considerable monthly fluctuation in the participation rate but the current rate of 65.3 per cent is a long way below its most recent peak in November 2010 of 65.9 per cent.

What would the unemployment rate be if the participation rate was at that last November 2010 peak level (65.9 per cent)?

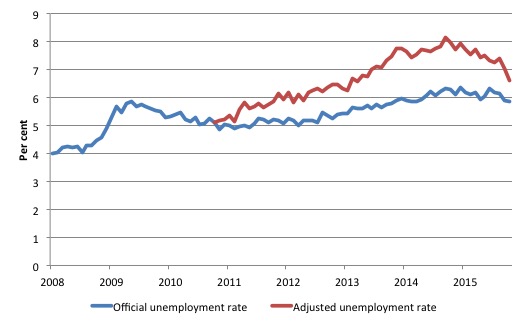

The following graph tells us what would have happened if the participation rate had been constant over the period November 2010 to November 2015. The blue line is the official unemployment since its most recent low-point of 4 per cent in February 2008.

The red line starts at November 2010 (the peak participation month). It is computed by adding the workers that left the labour force as employment growth faltered (and the participation rate fell) back into the labour force and assuming they would have been unemployed. At present, this cohort is likely to comprise a component of the hidden unemployed (or discouraged workers).

Total official unemployment in November 2015 was estimated to be 739.1 thousand. However, if participation had not have fallen relative to November 2010, there would be 840.3 thousand workers unemployed given growth in population and employment since November 2010.

| The unemployment rate would now be 6.6 per cent if the participation had not fallen below its November 2010 peak of 65.9 per cent. |

The difference between the two numbers mostly reflects, in part, the change in hidden unemployment (discouraged workers) since November 2010. These workers would take a job immediately if offered one but have given up looking because there are not enough jobs and as a consequence the ABS classifies them as being Not in the Labour Force.

There has been some change in the age composition of the labour force (older workers with low participation rates becoming a higher proportion) but this only accounts for about a 1/3 of the shift. The rest is undoubtedly hidden unemployment.

Note, the gap between the blue and red lines doesn’t sum to total hidden unemployment unless November 2010 was a full employment peak, which it clearly was not. The interpretation of the gap is that it shows the extra hidden unemployed since that time.

In recent months, this gap has shrunk quite substantially as participation has risen.

Hours worked – fell in November 2015

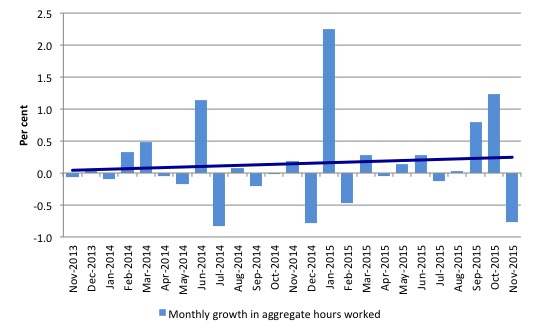

Aggregate monthly hours worked decreased by 12.7 million hours (0.8 per cent) in November 2015 in seasonally adjusted terms.

This is a surprising result given the rather substantial increase in full-time employment. One interpretation is that full-time workers are working shorter hours and the substantial growth in part-time employment is that the lower end of the hours distribution.

The following graph shows the monthly growth (in per cent) over the last 24 months. The dark linear line is a simple regression trend of the monthly change – which depicts a weak positive trend. You can see the pattern of the change in working hours is also portrayed in the employment graph – zig-zagging across the zero growth line.

Conclusion

In general, we always have to be careful interpreting month to month movements given the way the Labour Force Survey is constructed and implemented.

The last two month’s data from the ABS have really stretched credibility given how strong employment is estimated to have been. Today’s figures are quite amazing although the third quarter GDP figures and the recent job advertisements data have indicated some strength in the economy.

However, the trends are somewhat positive given the rise in participation.

I remain in two minds as to whether unemployment has peaked or not. If the private investment plans (projected rather significant cuts) for the forthcoming year are realised then peak unemployment will be higher than it is at present.

The teenage labour market remains in a parlous state although it improved this month in terms of growth in part-time employment.

I consider this situation to warrant immediate attention by the Federal Government. The neglect of our teenagers will have a very long memory indeed and the negative consequences will be stronger given the ageing population.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill: If unemployment decreased AND the participation rate increased, how did aggregate hours worked decrease?

Are we all part timers now?

This is all angels on the head of a pin stuff.

The one inescapable fact is that unemployment at the present level of around 6% (overall) is unacceptable in anything resembling a civil society. Unemployment rates should be around 1 to 2% in a decently governed nation. In that situation there are people who can’t work and should be on some sort of disability or age pension and those who won’t work and can try their luck on the surfer circuit. And good luck to them. We need them too. Maybe they are the only people with any brains left in the country.

Dear Cambo (at 2015/12/10 at 13:12)

I mentioned the reason in the body of the post. It is a compositional effect – with full-time workers working less and the rise in part-time employment being at the bottom end of the hours distribution. That is why underemployment has barely moved.

And … no-one is convinced that the data is all that robust at present.

best wishes

bill

Could it be possible that declining real wages may be helping to boost employment ever so slightly.

“Philippine economy thrives as young workers stay in the country”.

That was the headline that greeted readers of the FT Asian edition of 8th November 2015.

OUTSOURCING is becoming a dynamic theme for many western companies. That, together with rapidly advancing IT capabilities and robotics, poses immense problems for governments combatting the lingering effects of GFC and its unemployment aftermath. Traditional outsourcing destinations like India are being joined by countries like Vietnam, where 60% of its 90m population is reportedly under 30 years of age.

JG is only part of the solution if, in addition, there are fundamental employment changes taking place on a world-wide scale which impinge not only on Western economic stability but also on its commitment to uphold the welfare model that an ageing baby-boomer generation now threatens to render unsustainable.

The Finnish experiment may yet provide a few straws as to the future direction of the wind.

JG is only part of the solution if, in addition, there are fundamental employment changes taking place on a world-wide scale which impinge not only on Western economic stability but also on its commitment to uphold the welfare model that an ageing baby-boomer generation now threatens to render unsustainable.

No. The only way that a JG can be not “part of the solution” is if a great power decides to bomb any nation that has a JG. Thinking that “fundamental employment changes” elsewhere will or can hurt a country with a JG or that practices functional finance is just plain wrong, a wild, baseless and illogical but very common overestimate of the magnitude and often the direction of effects of international commerce. People selling you stuff cheaper makes you better off, period. Punching yourself in the face makes you worse off, period. There is no reason to punch yourself in the face if people sell you stuff cheap, but that is the standard theory & practice today – but not the theory & practice of functional finance or MMT/JG.

That these “changes taking place on a world wide scale” or “an ageing baby-boomer generation now threatens to render unsustainable” any current “welfare model” is nonsense. Con men who want to destroy welfare states make up fairy tales about this, and convince suckers to believe them. A large part of the academic MMTers’ work is exposing and refuting this kind of stuff.

I would like comparison over the life time as signatory to Globalization