I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Capitalists shooting their own feet – destroy trust and layer management

There was a wonderful article – The Origin of Job Structures in the Steel Industry – written by Katherine Stone and published in 1973. It was part of an overall research program that several economists and related disciplines were pursuing as part of the radical economics that was being developed at Harvard and Amherst in the early 1970s. One of the major strands of this research was to understand labour market segmentation and how labour market structure, job hierarchies, wage incentive systems and more are used by the employers (as agents of capital) to maintain control over the workforce and extract as much surplus value (and hopefully profits) as they can. It challenged much of the extant literature which had claimed that factory production and later organisational changes within firms were technology-driven and therefore more efficient. The Harvard radicals found that to be unsustainable given the evidence. They also eschewed the progressive idea that solving poverty was just about eliminating bad, low pay jobs, an idea which had currency in that era. They showed that the bad jobs were functional in terms of the class struggle within capitalism and gave the firms a buffer which allowed them to cope with fluctuating demand for their products. It also allowed them to maintain a relatively stable, high paid segment (primary labour market) which served management and was kept docile via hierarchical incentives etc. I was reminded of this literature when I read a recent paper from Dutch-based researchers on the way firms have evolved in the neo-liberal era of precarious work. Much is made of the supposed efficiency gains of a more flexible labour market. How it spurs innovation and productivity through increased competition and allows firms to be more nimble. The entire ‘structural reforms’ agenda of the IMF, the OECD, the European Commission and many national governments is predicated on these myths. The Dutch research shows the irony of these manic neo-liberals.

The reference for Katherine Stone’s article is – Stone, K. (1973) ‘The Origin of Job Structures in the Steel Industry’, Radical America, 7(6), November-December, 19-66.

It was finally published as ‘The Origins of Job Structures in the Steel Industry, 6 Review of Radical Political Economics 27 (1974). It was reprinted in Labor Market Segmentation 27-84 (edited by Richard C. Edwards, Michael Reich, and David M. Gordon, Heath, 1975); in Root and Branch: The Rise of the Workers Movement (Fawcett, 1975); in Complex Organizations: Critical Perspectives (edited by Mary Zey-Ferrell and Michael Aiken, Scott, Forsman and Company, 1981); and translated in Swedish in Klass-Maktoch Arbetsdelning (Archives Studies, Stockholm, 1987).

Katherine Stone, now a labour law professor at UCLA, studied the evolution of the job structures and management hierarchies in the C19th steel industry in the US. It is a long article but worth reading if you are interested in these things. I read it back in the late 1970s when I was working on segmentation theory.

Her essential argument is that in the C19th:

… work in the steel industry was controlled by the skilled workers. Skilled workers decided how the work was done and how much was produced. Capitalists played a very small role in production, and there were yet few foremen. In the last 80 years, the industry has transformed itself, so that today the steel management has complex hierarchy of authority, and steelworkers are stratified amongst minute gradings along job ladders. Steelworkers no longer make any decisions about the process of steel.

Why did this happen?

Katherine Stone wrote:

Out of their efforts to gain control of their workers and prevent unified opposition, the steel employers set up the various structures that define work today.

The major changes occurred between 1890 and 1920 and the employers began by busting the steel workers’ union. Then the management confronted the two-fold problem: making the workers work harder and stopping them uniting in rebellion.

To maintain discipline of the increasingly hostile workforce, the managers created “a new labor system”, which used a range of techniques to make “workers’ individual “objective” self-interests congruent with that of the employers and in conflict with workers’ collective self-interest”.

Such things as “wage incentives” coupled with “new promotion policies” worked to divide and conquer the workforce.

She traced the way in which the management secured control of the steel workplace using time-and-motion management techniques pioneered by – Frederick Winslow Taylor – the founder of so-called Scientific Management.

Stone showed that the introduction of these assembly line type techniques “narrowed skill differentials between the two grades of workers, producing a workforce predominantly ‘semi skilled’.”

To avoid this homogenisation feeding into unity, “elaborate job hierarchies were being set up to stratify them”.

It is a sorry tale and well worth reading in its totality.

She concluded thus:

The institutions of labor, then, are the institutions of capitalist control. They could only be established by breaking the traditional power of the industrial craftsmen. Any attempt to change these institutions must begin by breaking the power the capitalists now hold over production. For those whose objective is not merely to study but to change, breaking that power is the task of today. When that is done, we will face the further task of building new labor institutions, institutions of worker control.

I have already mentioned the work of Stephen Marglin in a previous blog or two. He wrote the 1974 classic article – What Do Bosses Do?: The Origins and Functions of Hierarchy in Capitalist Production – which showed that the rise of factory production and the division of labour that came with it:

… was the result of a search not for a technologically superior organization of work, but for an organization which guaranteed to the entrepreneur an essential role in the production process, as integrator of the separate efforts of his workers into a marketable product …

Likewise, the origin and success of the factory lay not in technological superiority, but in the substitution of the capitalist’s for the worker’s control of the work process and the quantity of output, in the change in the workman’s choice from one of how much to work and produce, based on his relative preferences for leisure and goods, to one of whether or not to work at all, which of course is hardly much of a choice.

[Reference: Stephen Marglin (1974) ‘What Do Bosses Do? the Origins and Functions of Hierarchy in Capitalist Production, Part I.’, The Review of Radical Political Economics, 6(2), 60-112.]

You can also read the 1975 follow-up – What Do Bosses Do? Part II.

Both Marglin and Stone were part of a radical study program examining labour market segmentation, the way in which capitalists created and implemented control functions to ensure the workers produced adequate quantities of surplus production, which, of course, is the source of profits in a capitalist system.

With this background in mind, I thought a recent paper by Alfred Kleinknecht, Zenlin Kwee and Lilyana Budyanto was pertinent.

The paper – Rigidities through flexibility: Flexible labour and the rise of management bureaucracies – was published in the latest issue of the Cambridge Journal of Economics, 39(5), September.

The context of the paper is the growing push by employer groups and neo-liberal governments to impose so-called “structural reforms” in labour markets as part of the austerity push.

The alleged motivation of these austerity proponents is based on their stated belief:

… that every obstacle to the ‘free’ working of markets reduces the market system’s capacity to automatically find equilibrium and allocate scarce resources efficiently … In this view, a trade union is an anti-competitive cartel organisation, preventing downward wage flexibility and keeping people unemployed. The same holds for generous social benefits and high minimum wages that cut off access to low-paid work. This line of reasoning would plea for removal of firing restrictions in order to make labour markets ‘more dynamic’ and change power relations in firms. All this seems to support ‘structural reforms’ of labour markets, which are now widely propagated as a response to the financial crisis.

But, as the authors note, the human cost of this forced precariousness in labour markets is that morale falls which is likely to reduce “innovation and productivity”.

It is a similar issue that Marglin and co were concerned with. The breakdown of morale when the capitalists started expropriating homeproduction.

There is a strong recent literature that suggests these ‘reforms’ (aka hacking into the job security and wages of workers to redistribute more real income to the top-end-of-town) undermine productivity, reduce innovation and work effort.

The paper compares the organisation of firms in two “varieties of capitalism”:

Anglo-Saxon liberal market economies (LME) versus Rhineland-type coordinated market economies (CME), paying particular attention to labour market institutions …

So it is another micro-focused study and focuses:

… on the role of social capital on corporate governance, i.e. the role of trust, loyalty and commitment.

The issues of trust, loyalty and commitment were, of course, central to the sorts of considerations that Stephen Marglin and Katherine Stone were also interested in.

The work of Marglin and Stone was focused on the beginnings of industrial production and the way in which the capitalist class had to introduce a control function because they couldn’t trust the workforce to work hard and long enough to generate the surplus production that was the source of capital accumulation and maintenance of the capitalist hegemony.

The recent article is focused on the contemporary evolution of capitalism as a sense of acquired “trust, loyalty and commitment” has broken down as the capitalists became too greedy.

The basic contention is that:

… ‘low road’ Human Resource Management (HRM) practices in the Anglo-Saxon style reduce the loyalty and commitment of workers, thus increasing the need for management and control … flexible work practices reduce trust …

They cite a sparse literature that supports that contention.

The authors use a unique Dutch database which has information on firms that are “still of the ‘Rhineland’ (CME) type” and a group of firms that have “adopted various elements of Anglo-Saxon LME” – that is, invoked “low road HRM practices”.

The principle break from the CME model has been the substantial increase in:

… the number of flexible workers, i.e. people on temporary contracts, manpower agency workers or ‘self-employed’ freelancers, increased substantially.

The authors estimate that up to 35 per cent of the Dutch workforce is now working in these precarious circumstances.

I noted when I was Portugal in early September how part of the austerity push has been to increasingly allow firms to hire so-called ‘non-contract’ workers which means they can escape all the statutory requirements including minimum wage rates, holiday pay, sick pay etc.

The effective minimum wage has plunged well below the legal minimum wage as a consequence.

As similar trend has been accelerating in the Netherlands and that shift has allowed the researchers to test the differences within firms that have adopted the neo-liberal, ‘race-to-the-bottom’ path against those that still operate in the CME tradition.

The “two indicators of flexible labour: (i) percentages of workers on temporary contracts and (ii) people hired from manpower agencies plus freelance (‘self-employed’) workers” are used to explain (via statistical analysis) differences in the “management ratios” within firms.

That is, how many managers and control/supervision staff there are to the total workforce in the firm.

They use a range of ‘control’ variables: firm size, firm age etc.

So what did they find in terms of differences in management practices (ratios) between the “high road” and “low road” firms?

I will leave it to you to study their methodology and statistical techniques. My view is that they are sound.

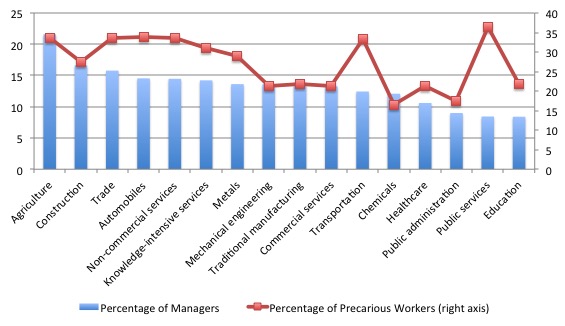

I produced the following graph from their underlying dataset. It shows the 16 industrial sectors and their corresponding management ratios (left-axis, blue columns) and the proportion of precarious workers (right-axis, red line).

With some exceptions, the lower is the proportion of precarious workers the lower the management ratio. In statistical terms, the relationship is strong.

The conclusions of the study are:

1. “sectors such as healthcare, education, public services or public administration have smaller management bureaucracies compared with private business firms. Possible explanations are higher trust and loyalty due to possibly lower rates of job turnover, the latter being favoured by typically high rates of trade unionisation in such sectors.”

2. Contrary to popular opinion, “larger firms have relatively lower management ratios than their smaller counterparts.”

3. “using higher shares of temporary workers, manpower agency workers and self-employed (freelance) workers is related to heavier management bureaucracies.”

4. “The deregulation and privatisation campaign of the 1980s and 1990s often suggested that we could choose between two opposite allocation principles: markets or bureaucracies. At least in the case of the labour market, our above results suggest we get both: thicker management bureaucracies and higher transaction costs within firms as a response to deregulation of protective labour market institutions.”

Conclusion

So it is rather ironic that the greed that has led governments to support the destruction of job security, the race-to-the-bottom wage structures, and the de-skilling of the workforce actually ends up costing firms in terms of innovation, lower productivity, and bloated management structures.

The higher management ratios – lots of petty middle managers checking up on workers all the time, filling out forms, having managing-for-performance interviews with their workforce and all the rest of the crazy overkill – are the result of the reduction in trust and loyalty that has accompanied these labour market changes.

They fit squarely into the literature on capitalist control.

Upcoming Events

Finland, October 2015

I am visiting Finland between October 7-11, 2015 and will be giving a number of presentations and talks during those four days.

1. Thursday, October 8, 2015 – SOSTE Talk 2015.

SOSTE is the “Finnish Federation for Social Affairs and Health is a national umbrella organisation that gathers together 200 social and health NGO’s and dozens of other partner members.”

I am their guest and I will be speaking at their annual conference – SOSTE Talk. The topic will be on Full Employment and how governments can achieve it.

I will be speaking between 9:00 and 10:30.

2. Thursday, October 8, 2015 – Austerity and Beyond – University of Tampere

After a 90 minute train trip from Helsinki to Tampere I will be speaking at the University of Tampere on the theoretical and political background of Eurozone austerity. There will be two discussants and a free conversation to follow.

The presentation and discussion will run between 15:00 and 18:30. All are welcome.

The location is Tampereen yliopisto (University of Tampere), Kalevantie 4, 33014 Tampereen yliopisto Tampere, Finland.

For more details E-mail: kirjaamo@uta.fi

3. Friday, October 9, 2015 – Guest Lecture at University of Helsinki – Economic Austerity and the Alternatives.

The Topic will be similar to the discussion at the University of Tampere although I will branch out and discuss Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) undoubtedly.

There will be two discussants and an open discussion to follow.

The event is free and open for everyone. It is organized by the Finnish Society for Political Economy and the Department of politics and economics, University of Helsinki.

The Finnish Karl Marx Society has promised to organise a good quality video broadcast from the event which will be available on YouTube soon afterwards.

The event will run from 17:00.

The location is Unionikatu 40, 00170 Helsinki, Finland.

Here is the promotional poster for the Helsinki event:

Newcastle, October 21, 2015

On October 21, 2015, I am a keynote speaker at the Poverty and Inequality Forum being held at the Newcastle City Hall and organised by NOVA. More details to follow.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“2. Contrary to popular opinion, “larger firms have relatively lower management ratios than their smaller counterparts.””

I’d suggest that’s because larger firms have more staff overall. Smaller to mid-level firms tend to twist arms more effectively and can actually get more from less – hence the greater management strong arm force.

Once a firm gets large enough that it starts to operating in the oligopolistic layer, then it starts to accumulate lower level staff as sort of a totem of power. Management starts to judge its social status amongst itself based on their ‘headcount’. That’s when the entropy levels builds up as management layers start jostling for political position within the firm rather than getting on with the objectives of the firm. The amount of ‘busy work’ goes up exponentially.

It’s all very amusing to observe but pretty obvious once you reject the myths of capitalist ‘perfect competition’.

I’d recommend the Anarchist FAQ for a summary on the domination of Big Business and other failures of the various capitalist and socialist structures. Anarchists tend to struggle with answers, but I find they are pretty good at coming up with the questions.

Dear Neil Wilson (at 2015/09/30 at 15:22)

The study controlled for firm size. So the results take any scale effects into account but still the management ratios are higher in the Anglo-type firms.

best wishes

bill

Milan Kundera said – “The struggle of people against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

In our society it looks like amnesia is a highly contagious disease.

The What Do Bosses Do? Part II link is broken.

Dear Allan (at 2015/09/30 at 17:34)

Thanks for the feedback.

I have fixed the link. They moved the resource from when I last accessed it.

best wishes

bill

Better to live as a Franciscan in a cash economy then become trapped in the corporate web.

Speaking as a part time human donkey today , it is a much better life then wasting your time tokens in a fordist factory.

However social connections must be strong

You must also hold savings or better yet a national dividend so as maintain bargaining power.

Unions do not work , they never have.

All of capitalism’s meaning and benefit to society is lost when the distribution of the direct government money needed to form capital is unequal; which is always, it never has been equal. Workers were under the control of old money from the beginning, and that will not change under the current political-economic paradigm.

Only those with access to government money can even be deemed credit worthy by commercial banks and this too is decided almost entirely by private parties rather than democratically elected governments. Perhaps more than a job guarantee is needed to right this wrong? Only when the workers themselves have become the capitalists can we have truly “free” markets, within a sensible democratically decided regulatory framework..

“Capitalist control”. Has anyone ever worked at a non-capitalist factory? I worked for one month in 1988 in former Czechoslovakia (as a student). Plastimat Zavod Tachov – making plastic boxes. The town was also famous for its uranium mine. “In capitalism some individuals exploit the others, in socialism it is the other way around”.

Until people understand why communism, socialism and other similar systems utterly failed on every attempt we won’t move the debate forward. But these are facts. Why can’t these exploited and persecuted by foremen workers organise a cooperative here in Australia instead of just complaining? There is enough “chardonnay socialists” to “put your money where your mouth is” and provide capital. Now an interesting observation – cooperatives either fail or evolve into normal, for-profit enterprises where “some individuals exploit the others”. Of course there is Mondragon, Kibbutzim, etc. But these cases actually prove my point. They are either economically marginal or have evolved into for-profit.

Why did the Soviet Union fail and communist China survived? Because they introduced proven to work capitalist forms of production (“free market”) instead of toying with Gorbachev’s perestroika-destroyka.

How are Cuba or North Korea or Venezuela doing?

Why did communism fail? Because of the lack of public support? But 98-99% of people voted for the communist party on all “free and democratic” elections until the bitter end.

The real reason (overlooked by “progressive” economists because it is inconsistent with the axioms and dogmas) is because of total microeconomic inefficiency inherent to non-capitalist enterprises. People didn’t bother to work unless they were terrorised by the communists (what eased off after 1956). There was no risk of being sacked. “Czy sie stoi czy sie leży pięć tysięcy się należy” (whether you are standing or lying flat you are entitled to your PLZ 5000 salary). People would steal (privatise) what was “common” precisely because it did not belong to the owner – it belonged to the state or to “nobody”. Communism was efficient during the war. After the war bureaucracy overgrew the economy since it was a command system. The plans to retrofit the market mechanism (“market socialism”) worked only to some extent (in Yugoslavia and Hungary). What Brus and Laski proposed (in “From Marx to the Market”) was abolishing the dogma of state ownership of the means of production. This was actually implemented in China – the system they implemented is called “state capitalism”. In Eastern Europe state property was privatised (often stolen by the members of the communist apparatus) when the system collapsed under its own weight.

Why would anyone even marginally educated make attempts to unlearn the history and resurrect the socialist utopia zombie?

Adam K.

Life expectancy in Cuba is much greater than it is in the USA.

“total microeconomic inefficiency inherent to non-capitalist enterprises”

This claim is absolute nonsense. Airports / Airline industry being one of many examples.

“Has anyone ever worked at a non-capitalist factory?”

Pretty much everybody. Internally firms are usually centrally planned.

“cooperatives either fail or evolve into normal, for-profit enterprises where “some individuals exploit the others”.”

They don’t always. I live near a very successful equal wage co-operative that is actually a pretty big distribution firm within its market sector (and as far as I know the largest equal wage employer in Europe). Admittedly it’s bang in the market sector that ethically oriented individuals tend to want to work in, but still it functions and operates successfully.

There’s always a queue for membership positions.

“The study controlled for firm size.”

Sorry. What I meant was that large firms tend to have *relatively* more staff overall (obviously they have more staff overall!) Managers don’t have secretaries in smaller firms, but they tend to in larger ones. HR departments only spring up in larger firms, etc.

All of those cause communication overhead which is where the inefficiencies in large firms start to build up. If competition worked that would cause larger firms to fall apart, but once you cross a certain size you enter an oligopolistic structure where you’re protected from the majority of the competition by the scale economies and political power size gives.

Alan,

Totally disagree.

1. As far as I know people keep migrating from Cuba to the USA not the other way around. If socialism is so great why haven’t unemployed and poor chosen living in the country where “life expectancy is longer”? BTW this only shows how bad health care system in the US is.

2. State-owned enterprises in a capitalist country have pretty much the same management rules as private companies. Regarding work organisation in a so-called “real socialism” the level of absurdity in absolutely everything was staggering. The main problem was the level of bureaucratic control. Wanted to travel overseas? Wanted a larger house? Pay a bribe. Wanted a car? Wait 5 years for the “coupon” or pay a bribe. Wanted to earn more? Forget about it – working harder won’t help – or join the Communist party or Secret Service. Or work for the grey sector and pay bribes. Wanted to invent something? This would go against someone’s interests. Go and migrate (but you can’t).

We ended up with food rationing in one of the most fertile countries in Europe. This is how well work was organised in state-owned farms. We can juggle words saying that every company has elements of central planning – but this is not the point I am trying to make.

If you have never lived in socialism, you don’t know what I am talking about. It wasn’t in fact “evil” and there were funny aspects of everything. Education was free. Health care was rather primitive but also free. Food was a bit more healthy because one wouldn’t eat too much sugar and fatty meat (due to the rationing).

It was the control of the Party and the state apparatus over the individuals what was the worst thing. Here in the West “proper” you can be poor but unless you happen to be in jail, nobody, even the most toxic corporations or banks won’t tell you what you have to do. You may not have a job but you have personal freedom (that’s why even homeless people living on the streets of NYC don’t want to move to Cuba or Venezuela). In socialism you would probably have a job but your effort would be mostly wasted (despite no surplus value extracted – so what?). “Real socialism” was a system of universal wastage.

Socialism cannot exist without state control over the individuals because some people want to have or consume more then the others and they are willing to work harder to achieve that goal. Later these anti-social (or anti-socialist) individuals want to employ others to start making profits – to amplify their work. If the state doesn’t prevent people from owning means of production and hiring labour, the emergence of capitalist order is a natural process as long as basic property rights are enforceable. I agree with some elements of the critique of the current neoliberal order and I think that capitalism should be “tamed” but I strongly disagree with the assumption that capitalism as such is bad. “Real-existing socialism” was far worse.

“that’s why even homeless people living on the streets of NYC don’t want to move to Cuba or Venezuela”.

Maybe they can’t afford the airfare? You know, being, er, homeless and destitute.

“(that’s why even homeless people living on the streets of NYC don’t want to move to Cuba or Venezuela).”

As if that is a real option they’ve been given and considered but refused… Extreme poverty in Cuba and Venezuela has been reduced a lot. Ask them if they are far worse now and you’ll get a different answer.

If “real socialism” ever existed is debatable.

“Why would anyone even marginally educated make attempts to unlearn the history and resurrect the socialist utopia zombie?”

We are not. We are trying to fix capitalism. Perhaps some criticism of the actual proposals?

As far as I know people keep migrating from Cuba to the USA not the other way around. If socialism is so great why haven’t unemployed and poor chosen living in the country where “life expectancy is longer”?

Because Cuba isn’t socialist, has never been socialist and doesn’t even superficially resemble a socialist system. To the contrary the closest analogue is a conservative aristocracy. People hate living in conservative aristocracies.

BTW this only shows how bad health care system in the US is.

Shows a lot more than that, for those with eyes to see and ears to hear.

Regarding work organisation in a so-called “real socialism” the level of absurdity in absolutely everything was staggering. The main problem was the level of bureaucratic control.

Identical to working in a large corporation under capitalism.

Wanted to travel overseas? Wanted a larger house? Pay a bribe. Wanted a car? Wait 5 years for the “coupon” or pay a bribe. Wanted to earn more? Forget about it – working harder won’t help – or join the Communist party or Secret Service. Or work for the grey sector and pay bribes. Wanted to invent something? This would go against someone’s interests.

Same dynamic as in capitalist societies, where bribes are paid to government officials for the purpose of guaranteeing profits by granting firms market power. Of course in capitalist societies the greatest rewards are disbursed for fraudulent behaviors.

We ended up with food rationing in one of the most fertile countries in Europe.

I can’t think of a capitalist country which has not endured rationing.

If you have never lived in socialism, you don’t know what I am talking about.

Then you don’t know what you’re talking about, either.

It was the control of the Party and the state apparatus over the individuals what was the worst thing.

Yeah, we don’t have that sort of thing in the West.

Here in the West “proper” you can be poor but unless you happen to be in jail, nobody, even the most toxic corporations or banks won’t tell you what you have to do. You may not have a job but you have personal freedom

Yes, freedom to starve, to be randomly beaten by the police, to be harassed on a daily basis.

. . .that’s why even homeless people living on the streets of NYC don’t want to move to Cuba or Venezuela.

Interviewed all the homeless, have you? Tell you their lack of any funds whatsoever had nothing to do with where they live, did they?

In socialism you would probably have a job but your effort would be mostly wasted.

Socialist systems are by definition under the rule of consumer choice.

“Real socialism” was a system of universal wastage.

You have no definition for determining what constitutes a system of “universal waste.” Not when you defend a system in which Goldman Sachs pays drivers to continually move commodity metals around so owners can’t find them.

Socialism cannot exist without state control over the individuals. . .

No, conservative enslavement of the people cannot exist without state control of individuals.

. . .because some people want to have or consume more then the others and they are willing to work harder to achieve that goal.

The wealthiest and most consumptive in capitalist societies do not derive their incomes from work.

Later these anti-social (or anti-socialist) individuals want to employ others to start making profits – to amplify their work. If the state doesn’t prevent people from owning means of production and hiring labour, the emergence of capitalist order is a natural process as long as basic property rights are enforceable.

A-historical nonsense. Capitalism began with the passing of laws to deprive peasants of their means of support: the lands on which they lived. Once their self-sufficiency was confiscated they were compelled to work for the capitalist under brutal conditions. The system you defend was built on theft and continues to survive by theft.

Five star post from Ben Johannson .

Excellent work.