The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The concept of ‘one Europe’ under threat from austerity

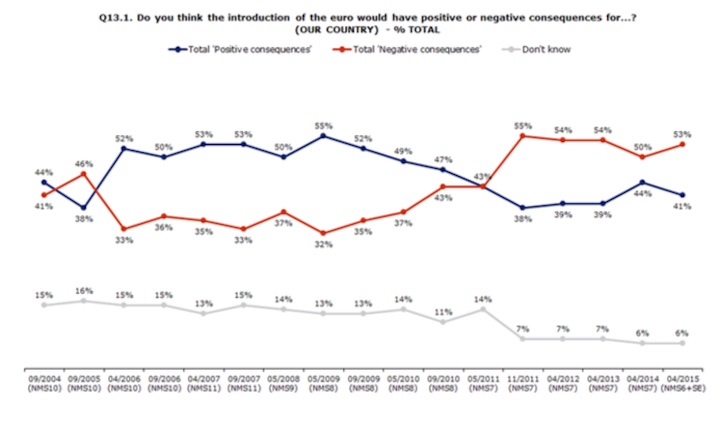

The EU Flash Barometer surveys provide information about public opinion in Europe. The latest Survey(No. 418) – Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the common currency – shows how confused people are in Europe at present. It seems that only 41 per cent of people in nations that “have not yet adopted the common currency” believe it would have “positive consequences” while 53 per cent think it would have “negative consequences”. That sounds as though they think the euro is a bad system. Well not exactly. The confusion might lie in the fact that the cruel system of austerity that the political elites have inflicted on the European nations is eroding the system of social stability that was established after the devastation of World War II. This is certainly the view taken by the ILO in a recent book it released. The ILO believe that the operations of the common currency (the austerity etc) is undermining the European Social Model, which is a core principle of an integrated Europe. So by insisting on maintaining the flawed currency system, the political elites are endangering the very thing they claim to revere – political integration – the ‘one Europe’.

In general, these surveys are misleading because they talk about the common currency in terms of banknotes and coins (asking people in nations that have not yet adopted the euro whether they have seen the notes etc) – that is, objects devoid of any ideology.

They do not talk about it in terms of the overarching Groupthink that administers the economic reality related to the common currency – such as, the Stability and Growth Pact, the lack of a federal fiscal authority to defend the nations against asymmetric and negative aggregate spending failures (such as the GFC).

The only question regarding economic policy is Q19.3 where respondents are asked what adopting the euro means “that their country will lose control over its economic policy”.

The results are:

A relative majority of people (47% vs. 46%) agree that adopting the euro will mean that their country loses control over its economic policy. This is the first time in the history of the survey that a relative majority of people have agreed with the statement.

Back in 2006, 59 per cent thought the nation would maintain control against 29 per cent who understood correctly that national sovereignty was dead once they gave up their currency issuance capacity.

So even now, with the GFC into its 7th year and austerity imposed from upon-high (Brussels, Washington, Frankfurt) crippling national prosperity, 46 per cent of people do not understand what the adoption of the euro means for the independence of a nation.

Confusion seems to reign supreme.

When asked whether the adoption of the “euro has been positive in the countries that have already adopted it”, 51 per cent agreed that it has whereas only 36 per cent thought it had been negative.

When the same survey question was asked in September 2007, just before the GFC and the subsequent austerity hit, the same percentage (51) agreed that the euro had had a positive impact in nations that had already adopted it.

That would seem to be a staggering outcome with some parts of Europe in Depression, and most in recession, as a result of the subsequent austerity. A majority of the respondents cannot see that the problem is the euro itself and the surrounding policy frameworks and rules.

But then try to reconcile that with the responses reported in the introduction. Repeat:

1. 53 per cent think that the “introduction of the euro in their country would have negative consequences” whereas only 41 per cent thought it would have positive consequences for their nation as a whole. In May 2009, the responses were 55 per cent positive, 32 per cent negative.

2. 47 per cent think that “the introduction of the euro will have negative personal consequences” against 44 per cent who thought it would have positive personal consequences. In September 2007, the proportions were 49 per cent positive against 34 per cent negative.

The following graph shows the evolution of the responses about the consequences for the nation.

So a majority in nations that haven’t already adopted the euro think the common currency has had an overall positive impact on nations that have adopted it, but consider it would have a negative impact if their nation adopted it on the nation itself and on them personally.

Apart from not understanding what the common currency means for sovereignty and the implications of the fiscal rules that accompany the common currency, these results would appear to be inconsistent.

The confusion might be related to “Europe losing its soul”, which is the (part) title of a new book published on April 27, 2015 by the ILO (in partnership with Edward Elgar UK) – The European Social Model in Crisis: Is Europe losing its soul? (370 pages).

A 52-page precised version of the book is available – HERE.

in my my current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015), I argued that the imposition of the common currency and the way in which fiscal flexibility has been restricted has not only failed but also endangered what I referred to as the European Project, which was an ambitious political plan to bring sustained peace and prosperity to the Continent.

I note that today, the UK Guardian Editorial (June 30, 2015) is running that line now – The Guardian view on the Greek crisis: the European project itself is at stake – although it seems to, wrongly in my view, equate the viability of what it calls the Project with continuation of the monetary union.

I clearly think that maintaining the EU as a political construct to handle big transnational challenges – climate change, rule of law, migration etc – is a quite separate exercise to the monetary union. The sooner they abandon the currency union the better.

The ILO book provides a cogent analysis to suggest the aberrant behaviour of the political elites in Europe that have blindly insisted on imposing fiscal austerity when exactly the opposite was required is destroying the very soul of the European post World War II consensus model.

The conjecture entertained in the ILO book is that:

… under the pressure of the financial crisis and following the introduction of austerity packages to reduce debt, we witnessed most European countries changing – often hastily – several elements of that model: social protection, pensions, public services, workers’ rights, job quality and work- ing conditions and social dialogue.

The – European Social Model – is built on the fundamental principles built into Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC):

… promotion of employment, improved living and working conditions … proper social protection, dialogue between management and labour, the development of human resources with a view to lasting high employment and the combating of exclusion.

It combines with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights to define an “underlying principle is one of solidarity and cohesion: that economic growth must serve to boost overall social wellbeing, and not take place at the expense of any section of society”.

The ILO book says that while “there is no official definition of the European Social Model” there is a long history of practice and dialogue that allows one to map out the main characteristics.

The ILO define “six main pillars”:

1. “Increased Minimum Rights on Working Conditions”.

2. “Universal and Sustainable Social Protection Systems”.

3. “Inclusive Labour Markets”.

4. “Strong and Well-Functioning Social Dialogue”.

5. “Public Services and Services of General Interest”.

6. “Social Inclusion and Social Cohesion”.

The implementation of this vision differs across the different countries and the variations are typically in terms of the proportions of support given to pensions and other income support, tax levels, and labour market protections.

So there isn’t ‘one’ European Social Model but there is sufficient commonality of purpose to distinguish the European emphasis on solidarity from the American or Australian approaches.

The ILO book argues that this “social dimension, accompanying and even stimulating economic growth, undoubtedly represents the soul of the European Union, envied and copied by other regions and countries in the world”.

I would agree with that. I always thought that Europe had a sophisticated way of treating people that was unlike the way the Anglo Saxon nations (yes, I exclude Britain from Europe!) saw the role of the state in relation to its citizens welfare. I don’t think that now.

The question the ILO books poses: “Is Europe currently losing this legacy?”.

The hypothesised consequences of losing the “legacy” are from “the social side … ever growing inequalities, social exclusion and poverty, and … increased social conflicts” and from the “economic side … unbalanced growth and … the long-term sustainability of our economic model”.

The ILO argue that despite the apparent acceptance of a ‘social model’:

Several member states have repeatedly tried to undermine the social rights described above in the belief that they are costly for enterprises and lead to much too rigid labour markets.

These states do not consider sharing of the productivity gains made by a nation should necessarily be shared. Maintaining real wages growth in line with productivity growth and allowing those on income support to share in the productivity gains was a fundamental precept of the Post World War II consensus.

But the challenges to the ‘social model’ have come from “Neoliberal theorists” who “believe in the ability of markets to determine optimal levels of wages and employment” and that “social allocations by the state – such as unemployment benefits – would have the effect of disincentivising work and encouraging voluntary unemployment”.

This debate has led to an evolution of the concept of the ‘social model’ – such as “reforms on pensions to ensure their long-term viability” – but:

It is … after the crisis that most European countries entered into a period of rapid changes in social policy and started to rapidly implement decisions and reforms that in a few years will modify their overall social policy model.

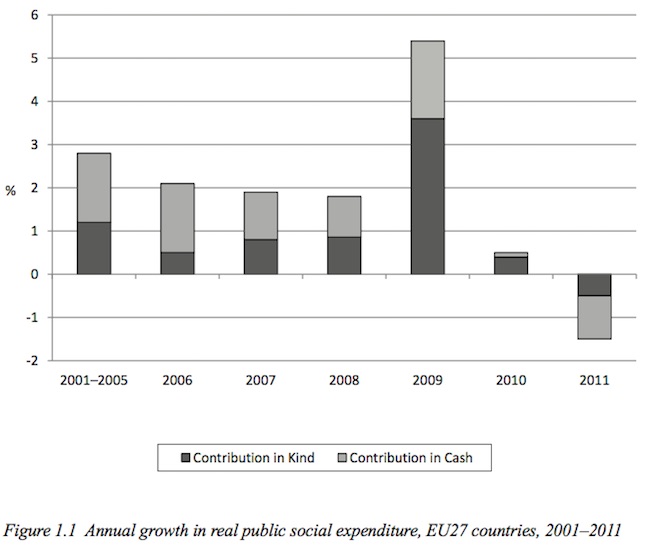

In the lead up to the crisis, “real public social expenditure” was “relatively stable” but jumped in 2009 as the automatic stabilisers built into national government fiscal parameters were triggered by the “massive job losses and increased unemployment”.

The increase in real social expenditure was “driven mainly by increases in unemployment expenditure, but also in health and disability and old age and survivors’ expenditure”.

However, the imposition of fiscal austerity from 2010 has seen the:

the situation totally reversed, when annual spending growth slowed sig- nificantly, followed by a fall in social expenditure in 2011. This did not mean that needs were lower in 2010-2011 compared with 2009 but reflected instead a U-turn, or shift, in governments’ public expenditure policy from 2010.

The following graph (Figure 1.1 in the book) tells the story. It gets worse in the years since 2011.

The ILO notes that policy makers cut real social expenditure in Europe even though “rising unemployment and increased poverty should have resulted in an increase in expenditure”.

That is, discretionary fiscal policy should be ‘counter-cyclical’ – work against the private spending cycle. It should never be pro-cyclical when private spending is falling.

There is no text book in economics that will support pro-cyclical austerity.

The ILO notes that “adjustments were most severe in countries in which the public and budget deficits were highest (as in Greece, Portugal and Ireland)”, and the “scale of austerity is unprecedented in post-war European history”.

Much is made of the increased public debt during the crisis, but the ILO correctly notes that the increase “were not due to social expenditure as such … but were explained mainly by the decision of governments to refund their banks during the financial crisis”.

The ILO note the “paradox, with social policy being attacked within austerity plans despite the fact that, first, it was not the cause of the crisis and second, it had helped to preserve social and economic outcomes in the first phase of the crisis.”

They do not mention the obvious, however. That the attacks on social expenditure really had nothing to do with sustainable public finances. Rather, the neo-liberal ideologues took advantage of the situation to expunge elements of public spending that they had long opposed.

Cutting welfare and pensions is one component in their desire to tilt the playing field further in favour of corporations and away from workers.

The ILO book examines the ways in which the “six pillars of the ESM have been adversely affected”.

We see that “Workers’ rights and working conditions” have been attacked:

1. Basic workers’ rights have been undermined – “restrictions on the right to strike” imposed; restrictions on “free and voluntary collective bargaining”.

2. “Unilateral employers’ decisions on working conditions” – examples are given where working hours and wages have been altered in favour of the employer without consultation, among other capricious acts by employers.

3. Wage cuts “as part of internal devaluation strategy” – “on the direct advice of the Troika” many nations started cutting labour costs in a more or less unilateral manner. Tripartite agreements “were not always respected”, and in many countries minimum wages were frozen and real wages fell.

The ILO say that “the minimum wage was even cut in nominal terms by 22 per cent in Greece, again following requests from the Troika”. But still the vultures want more!

Most of the “changes in the collective bargaining process are aimed at breaking regular adjustment mechanisms with regard to wages”.

In other words, entrenching the redistribution of national income to profits even beyond the crisis.

Further, competitiveness is not just about labour costs. Profits form a component of total sales price but the IMF and its mates in Europe have never advocated cutting profit margins. In fact, it seems that the Troika has actively thwarted attempts by the Greek government to lift tax rates on corporations.

4. “Violations on occupational safety and health” – the progress over the 20 years leading up to the GFC saw “constant progress” in improving OS&H standards.

But the austerity and small business cutbacks have seen major retrenchments in this area.

The ILO also examine the costs of making labour markets more flexible since the GFC:

1. “Facilitating entry and exit” – job protections have ben cut. Summary dismissal is now much easier and probation periods with lower wages for new entrants lengthened and widened.

2. “Further flexibilizing work contracts” – with temporary workers easier to sack, “most countries decided to make recourse to this form of employment much easier”. Many more workers are now on fixed-term contracts and temporary contracts. For example, in France, 90 per cent of new contracts are from “temporary agency work”.

In Germany there has been a massive escalation in the “number of mini-jobs” and 86 per cent are occupied by low-wage workers. More nations are permitting unlimited flexibility in hours contracts (such as the zero-hours jobs in the UK).

Underemployment has skyrocketed throughout Europe. From 7 per cent pre-crisis in Cyrpus to 53 per cent of the labour force. Or from 11 to 41 per cent in Ireland.

3. Training has been starved of funds.

The ILO also considered retrenchments in “social protection”:

1. “Drastic cuts in both unemployment and social benefits” – eligibility criteria have been altered to reduce recipients and duration of benefits has been shortened.

2. “A more structural shift from universal to targeted protection”.

3. “Pensions heavily reformed (both amounts and systems)”.

4. “A general fall in social expenditure”.

The ILO also argued that the narrative has changed such that “Social dialogue” is now “viewed as an obstacle rather than a lever”. The elements of this retrenchment include:

1. “Tripartite agreements weakened or stopped”.

2. “Collective bargaining under attack”.

3. “Transformation of industrial relations in the public sector”.

The ILO argue that there has been an “unprecendented shock” to the operations of the public sector and the concept of public service:

1. “Employment withdrawal: non-replacement, jobs cuts and changed work contracts”

2. “Massive cuts in wages, bonuses and benefits”

3. “Fall in welfare provisions” – The “spending cuts … were massive in sectors such as health and education”. In Greece, education spending has been cut by 33 per cent (2008-13), 25 per cent in Latvia (2008-10) and 18.4 per cent in Portugal.

Finally, the ILO say that “cohesion” has been “neglected in the name of austerity requirements”. This retrenchment includes:

1. Widening regional imbalances – as funding declines.

2. “The growth of discriminatory practices … The growth of unemployment and social problems has led again to increased nationalism and some groups were stigmatized in the crisis”.

3. “Tax policies acting against social cohesion” – tax hikes in regressive VATs etc without compensation to poorer households. The ILO find that:

Similarly the tax burden has increased but not for the highest incomes – often with the argument that the rich are ex- pected to contribute more to investment and economic recovery – but rather for low or middle range income families.

Are you wondering what planet we are living on?

Overall, the ILO conclude that:

… while the European Social Model may have been called into question here and there before the crisis, the list of changes in most elements and pillars of the European Social Model since the crisis is formidable. While there are a few exceptions … all other trends show a general withdrawal of the state from social policy, first through massive cuts in social expenditure and reduced funding of education, health care and other public services, and second through radical reforms in a number of areas, such as social dialogue, social protection, pensions, labour market and social cohesion in general …

the changes are particularly severe in those countries that implemented an austerity package under the direct influence of the Troika …

Conclusion

The longer-term consequences of this vandalism to a model that maintained high levels of social stability through reduced inequality and rising material standards of living will reverberate throughout Europe long after economic growth returns.

In some countries, there is a jobless generation moving into adulthood – lacking education, lacking skills and denied work experience.

Suicide rates and health problems are rising.

And there is that thing we now call terrorism! Yet, for me, it is hard to tell who the terrorists are sometimes.

Remember Noam Chomsky’s article from 2002 – Who are the Global Terrorists?. He noted that “in US Army manuals” terrorism is defined as:

… the calculated use of violence or threat of violence to attain goals that are political, religious, or ideological in nature…through intimidation, coercion, or instilling fear.

That appears to describe the behaviour of the Troika perfectly. Violence, of course, can be psychological – the type that mass unemployment rates above 25 per cent generates.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Come on, Greece! Don’t succumb to the scares, vote ‘OXI’ and stick it to the terrorist troika!

“The EU Flash Barometar surveys provide information about public opinion in Europe. The latest Survey(No. 418) – Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the common currency – shows how confused people are in Europe at present. It seems that a small majority think ”

Out of place?

Bill,

You should approach The Guardian people at Comment is Free to commission an article. I’m sure they’d comply given the publication of your book (which you can plug).

cif.editors@guardian.co.uk

Like yourself, I once thought that Europe had an excellent social model that was better than the other countries you mentioned. And, also like yourself, I now no longer think so, at least as it is practiced. Which I am distinguishing from what they *think* they may be doing. And I am allowing for some of them knowing exactly what they are doing.

However, I harbor deep in my guts a (probably Utopian) hope that Europe will get out of this mess in a way that the social model, while damaged, is repairable. And so, I would suggest that the monetary union can continue if the neoliberal/neoclassical claptrap that has, for venal reasons, captured the “hearts and minds” of the various elites of Europe and others around the world is abandoned and the various distinct polities are better integrated, socially and politically, via a “more perfect union”, as the late Lamfalussy, and others engaged in the project, envisaged. But not otherwise. Unfortunately, it looks as though ‘otherwise’ is going to be the default position.

Addendum:

And what is incredibly short-sighted of the elites is that what they are doing will, in addition to destroying those they despise for one reason or another, will in the end also destroy themselves. For they are beneficiaries of the European Social Model. In destroying it, they undermine their own social, political, and economic security. Why it isn’t obvious to the various elites that security (and all that entails) for the few necessitates security for all is a mystery to me.

Dear larry (at 2015/07/01 at 19:40)

Yes, thanks. It was the nascent introduction which I forgot to delete.

best wishes

bill

Dear Phil

I have in the past and they claim they have a progressive economist commentating (Jericho) from Australia. His latest piece for the ABC shows just how progressive – meets neo-liberal – he is. He compares Australia to Greece purely on how large the public debt ratios are.

best wishes

bill

It is beginning to seem clear, and hardly just to me, that the eurozone is actually toxic. It deliberately has been set up, from Jean Monnai and on, to be dismissive of politicians and to leave the reins of control in the hands of bureaucrats. The troika shows just how incompetent and immune to results they are. Why would anyone with even a modicum of empathy keep pouring austerity onto a population which has suffered already from its pernicious effects since 2010. They have no skin in the game,which is wrong, and so care little beyond their assumed roles as guardians of Europe. It’s becoming not worth guarding.

Even some of the governing politicians in the states of Australia do not accept that they are not part of a sovereign government. Without a strong policy making central government their can be no policies aimed at lifting those states with lower living standards to a common standard.

In Australia an automotive plant was built in South Australia years ago and I would be reasonably sure that was a consequence of Commonwealth Government policy, just as the submarine and other naval vessel contracts were.

I suggest that the move to calling it a Federal Government is because conservatives hate the thought of common weal (common good).

Has the European Parliament ever made a decision to expend industrial production in Greece? I think not.

On ABC 7.30 tonight the former head of the World Bank stated that Australia has a resources economy. Even from before WW2 the then Labour Party realized that the Current Account situation would always present a problem if Australia failed to produce its own consumer durables, particularly when there were no known domestic oil reserves (liquid oil reserves are again almost non existent). A resources country is one that lives off its capital because what are resources if they are not capital assets.

Australian politicians, particularly in the current Commonwealth Government have lost sight of that CA problem.

Maybe they are determined to make Paul Keating’s “white trash of Asia” prediction come true.

….

A few years back I asked a lot of my continental friends about their respective nations social security and welfare state.

I percieve Britain to be part of Europe,and comparing it’s welfare state to the rest of the continent, Britain’s Bevin welfare state comes out ahead.

-healthcare free at the point of use,France+Germany have an insurance system.

-non-contributive universal unemployment benefits,on the continent you need to have paid into an industry/sector insurance scheme,places like Spain you need to have worked before receiving social security for a limited time of 6 months.In Italy there are no universal non-contributive benefits

-Housing benefit,Britain pays the most in housing benefit ,and it is paid based on income.(Britain does have a lot of structural policies when it comes to housing)

-until very recently ,there was adequate social housing and tertiary education was fully subsidised ,even living costs with “grants”

-longest state guaranteed paid holiday in Europe,if not the world(unless your on a zero hour contract)

The rest of western Europe don’t really provide as comprehensive a list of social security and benefits.

Not that there isn’t a lot of structural problems,and inequality,

But I think it is a myth to percieve the rest of western Europe as more egalitarian.If you spend any time with wealthy continentals ,they are terribly snobby.

Britain has always been a leader in terms of socialism and a welfare state.

Dear Bill

A monetary union doesn’t really require fiscal centralization or the same standard of living. What it requires is the same inflation rate for all members of the union. The reason is obvious: within a currency union, there can no longer be nominal devaluations or revaluations, which in fact prevent prevent real changes in the exchange rate. When the euro was introduced, it was agreed that all members would aim for an inflation rate of 2%. Some countries in Southern Europe went above that, but Germany and some other countries remained below that, thereby undermining the competitiveness of not only the “inflationists”, but also that of a country like France, which has scrupulously adhered to the 2% rule.

France, Spain, Portugal and Italy will not be able to solve their economic problems as long as they are monetarily tied to mercantilistic countries like Germany and the Netherlands. Mercantilism may be an unwise policy at the best of times, but within a monetary union it is downright anti-social.

Regards. James

The concept of ‘one Europe’ under threat from … Border controls coming back.

https://euobserver.com/justice/129403

An excellent article over at Bloomberg…

http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-07-01/europe-wants-to-punish-greece-with-exit

“In my more than 30 years writing about politics and economics, I have never before witnessed such an episode of sustained, self-righteous, ruinous and dissembling incompetence — and I’m not talking about Alexis Tsipras and Syriza…”

James, I think you are mistaken about fiscal centralization and that current events in Europe constitute a counterexample to your contention that currency unions do not need a fiscal centralization of some kind. For it to work in the way it should, as in the way it would in a truly federal system, you need a central bank that is not under the control of any of the union’s members but is controlled by the system-wide governing body. At the moment, the ECB is virtually if not entirely under the control of Germany and you can see how well that is working out. But fiscal centralization is not sufficient in itself. What is also needed is a central political organization, a government, that has been democratically elected and which has a central Treasury. A currency union in the absence of a political union is inevitably not going to work well under certain circumstances, like those we are experiencing at present.

MK10, I think it may be misleading to generalize from what Denmark is doing in regard to what it terms “irregular migrants”. While it is part of the EU and the passport-free Schengen area and has its currency pegged to the Euro, for inexplicable reasons as it is not part of the Eurozone, it has claimed that these controls are temporary. I am not saying you are wrong, only advocating caution about generalizing from Denmark’s current policies. Their problem is the number of non-EU migrants seeking what might be called sanctuary in Denmark, and the government is facing increasing anti-migrant feeling among the populace. Other countries are facing similar pressures. Will Europe be able to absorb all these refugees? I do not know the answer to that question. But it may well be, No.

Warren Mosler recently posted an interesting and, I would say, very likely correct interpretation — Syriza is aware of the Grexit option but will never go for it, entirely for political reasons.

Dear Larry

The EU is more a confederation than a federation. In a federation, there is a central government that is the most powerful entity in the country. The most powerful entity in the EU is the European Council, which simply consists of the heads of government of the member states. I agree that a monetary union would work more smoothly in a federation. Canada is a federal country. If, say, the economy of the province of Alberta were to enter in a deep crisis because of the collapse of its important oil sector, then Albertans would pay less tax to Ottawa and at the same receive more transfer payments. That would soften the blow. The blow would be softened even more if the federal government is responsible for important services such as health care and education, which is not the case in Canada.

However, a confederal monetary union, such as the EU, could set up an emergency fund that would help a member of the monetary if it underwent a severe demand shock. Such help would have to be given in order to enable the government to continue to fulfill its obligations to its citizens, not to bail out creditors. If all members of a monetary union have the same inflation rate, then demand shocks will be less frequent.

Regards. James

I know, James. My argument is that it must become a federation in order for the structure that they have partially constructed to work. And the chances of that happening now are remote. Which entails that the Eurozone will never properly work at all.