I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

So-called ‘free trade’ agreements should be strongly opposed

My header this week is in solidarity for the Greek people. I hope they vote no and then realise that leaving the dysfunctional Eurozone will promise them growth and a return to some prosperity. They can become the banner nation for other crippled Eurozone nations – a guiding light out of the madness that the neo-liberal elites have created. While Greece battens down against the most incredible attack on European democracy since who knows when – perhaps since the Anschluss that led finally to war breaking out a year later in Europe, one wonders how low the Brussels elite will go to preserve control of the agenda. They clearly lost control on Friday when the Greek leadership decided to go back to the people to determine whether they wanted more poverty-inducing austerity. In response, the Brussels gang along with their Washington mates at the IMF have come out with personal attacks, lies, threats and ridiculous dissembling. But that is what happens when bullies can’t bully. But while these events are rather extraordinary in historical terms, other insidious attacks on democratic rights and choice are on-going. One of the more startling attempts to undermine the capacity of elected states to deliver on their mandate to their electorates and hand over almost absolute power over the state to international corporations is the so-called Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

The TPP is being pushed under smokescreen of ‘free trade’, which is one of those classic neo-liberal con jobs like deregulation, privatisation, public-private partnerships and other ruses that imply that self-regulating private markets will deliver maximum wealth growth to all.

The corollary, of course, is that the state should remove the fetters of regulation on business, minimise its own economic footprint, and allow the corporate world to do what it does best – help us all.

The narrative is so obviously bereft that it hardly seems worth criticising any more. If the GFC proved anything it showed categorically that self-regulating private markets do not function efficiently and do not providing lasting benefits to us all.

We knew that already – the history of privatisation, outsourcing and the rest of the scams is littered with disasters, which are usually conveniently covered over with some gloss or another.

But the GFC brought it homein an undeniable fashion just as Greece – sorry for them – have been the most overt laboratory for the failures of fiscal austerity and the easy sounding but evil in practice ‘growth friendly structural reforms’ (aka hack as many public benefits from ordinary citizens and transfer as much national income to the rich).

But the TPP is seemingly reaching the apex of this Capitalist bastardry. We don’t know much more about it than we get by the good citizens who provide Wikileaks with documents.

The governments involved plead “commercial-in-confidence” as their reason for preventing a full public debate on the proposed TPP. They hide the negotiating details from us and then tell us that it is in our best interests for them to urgently sign of on it without the normal political oversight.

Australia has been down this route before when the national government signed the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement and the Japan-Australia Free Trade Agreement, which effectively prevented the elected parliament from legislating against any of the provisions in the respective treaties.

As Peter Martin reports in his Fairfax article today (June 30, 2015) – TPP – what we don’t know may hurt us:

… the parliament would be presented with an all-or-nothing choice. It could examine the TPP (after it had been signed) and either vote for or against it, but not change a word.

His article describes a farcical ‘consultation’ process that the Government claims provides the public with a chance to have input. Of course, “It’s hard to know that you need to write a submission if you don’t know what’s being proposed”.

There should never be any agreement between states which is not first fully disclosed to the people of each nation for their input through the usual channels.

A corporation should never have priority over a state and the citizens that the state represents.

From the leaked documents we know a bit about the TPP.

The aim of the treaty is to allow international corporations more freedom to operate across national borders without the usual oversight from the legislative environment imposed by the state.

The areas that the signatory states will lose the capacity to regulate include labour market regulations (job protection, minimum wages, etc), the cost of medical supplies, financial market oversight, environmental protection, and standards relating to food quality.

The controversial aspect of these agreements surrounds the so-called Investor State Disputes Settlement (ISDS) clauses, which set up mechanisms through which international corporations can take out legal action against governments (that is, against elected representatives of the people) if they believe a particular piece of legislation or a regulation undermines their opportunities for profit.

It is that crude. Profit becomes prioritised over the independence of a legislature and the latter cannot compromise the former. Our values have really become skewed in the ‘dark age’.

In other words, a democratically-elected government is unable to regulate the economy to advance the well-being of the people who elect it, if some corporation or another considers that regulation impinges on their profitability.

Corporation rule becomes dominant under these agreements.

The agreements create what are known as ‘supra-national tribunals’ which are outside any nation’s judicial system but which governments are bound to obey.

The make-up of the tribunals is beyond the discretion of a nation’s population and, as far as we know, will be heavily weighted under the TPP by the corporate lawyers and other nominees. The notion of accountability disappears.

These tribunals can declare a law enacted by a democratically-elected government to be illegal and impose fines on the state for breaches.

With heavy fines looming, clearly states will bow to the will of the corporations. Corporation rule!

There have already been some astounding decisions in these ISDS under other agreements, which have denied governments the right to introduce policies regarding environmental protection (for example, toxic waste safeguards, forestry management processes, etc).

Clearly, the secrecy in which the TPP is being finalised is a reflection of its toxic nature. The governments know that if the details leak out there will be an outcry and their political positions will become an object of focus.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) keeps a database on – Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) – which they say is “currently being redesigned and updated”. The so-called “reduced version of the database” makes for interesting analysis.

Since 1987, 24 per cent of the 608 cases taken out have been resolved in favour of the state being sued. There are still 58 per cent of the cases outstanding.

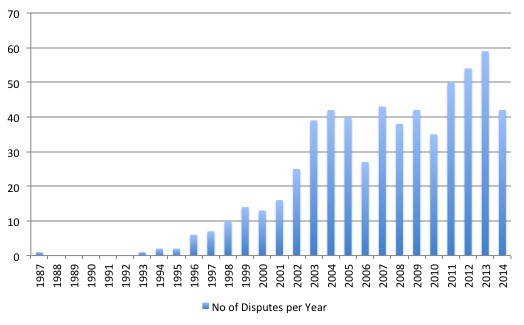

Here are some summary data that I gleaned from the database. The first graph shows the escalation in the ISDS cases since 1987.

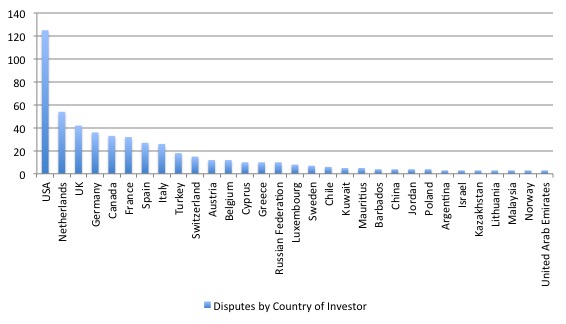

The next graph shows the top 30 countries of investors who sued various states. The US clearly dominates with American corporations taken action in 21 per cent of the total cases. Dutch firms also appear to be particularly litigious.

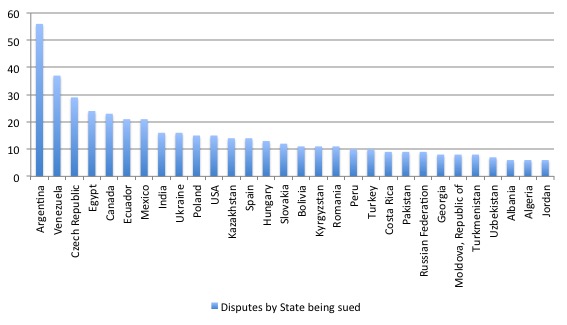

The final graph shows the disputes by state being sued for the top 30 states. Argentina is involved in 9.2 per cent of the total cases followed by Venezuela (6.1 per cent), and the Czech Republic (4.8 per cent).

What evidence is there that these agreements advance well-being? Answer: none. In fact, the evidence so far produced of prior agreements (noted above) tends to conclude that the operation of these agreements undermines the national welfare.

The Australian Productivity Commission released its latest – Trade and Assistance Review 2013-14 – on June 24, 2015.

The APC can hardly be described as anything other than a pro-market body. Its history is that it began life as the Tariff Board (overseeing the protection system in Australia) and in recent decades, became the government’s free market agency – arguing relentlessly for deregulation and privatisation.

So it is hardly a left-leaning organisation.

Its latest Review studied, among other things, the so-called “Preferential trade agreements”, which Australia has entered into in recent years (with China and Japan). These agreements are similar to what we expect will be in the TPP.

The Productivity Commission concluded that:

Preferential trade agreements add to the complexity and cost of international trade through substantially different sets of rules of origin, varying coverage of services and potentially costly intellectual property protections and investor-state dispute settlement provisions.

… The emerging and growing potential for trade preferences to impose net costs on the community presents a compelling case for the final text of an agreement to be rigorously analysed before signing. Analysis undertaken for the Japan-Australia agreement reveals a wide and concerning gap compared to the Commission’s view of rigorous assessment.

It notes:

1. The “proliferation of preferential trade agreements at the bilateral and regional level (referred to commonly as ‘free trade agreements’) is adding to the complexity and business transaction costs of the international trading system”.

2. The “practical impacts of agreements being entered into by Australia remain unclear and highlight the need for thorough evaluation of the negotiated agreement text prior to their signing.”

3. “In substance, the devil resides in the detail of these agreements and full and transparent analysis is not afforded to the final texts for many of them.”

4. “current assessment processes in Australia fall well short of what is needed to adequately assess the impacts of prospective agreements.”

5. “Current assessment processes do not systematically quantify the likely costs and benefits of negotiated texts to an agreement, fail to consider the opportunity costs of pursuing preferential arrangements compared to unilateral reform and ignore the extent to which agreements actually liberalise existing markets”.

6. “that services provisions negotiated under the ASEAN-Australia- New Zealand agreement added little if anything, to those already afforded by services commitments under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)” but exposed the Australian state to unnecessary risks.

The Productivity Commission also comments on the ISDS activity relevant to Australia. The national government is being sued by an international tobacco company for introducing plain packaging with health warnings. The company claims it undermines its profitability.

The Commission says:

The Australian Government continued defence of its tobacco plain packaging laws in a case brought by Philip Morris Asia in the Permanent Court of Arbitration and a number of countries in the WTO dispute settlement body. This case highlights the potential (and un- provisioned) contingent liability of Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) provisions in trade and investment agreements that confer procedural rights to foreign investors not available to domestic residents. The final outcome of the case is not expected to be known for some time. The ongoing costs to Australian taxpayers of funding the preparation and defence of the tobacco plain packaging legislation, and the ultimate ruling, are unknown, unfunded and likely to be substantial.

In other words, international corporations have more rights than local residents.

The TPP is one component of the corporate intolerance for democratic oversight by states. The agreements are being advanced by neo-liberal governments who think the role of government is to advance the interests of the corporations as a way of increasing wealth.

We already know that the distribution of income and wealth is becoming more skewed as the neo-liberal era continues.

These trade agreements are just dirty scams designed to continue the redistribution of income and wealth to the top end of the distributions and to further neuter the capacity of governments to act independently according to elected mandates.

They line up with fiscal rules, independent fiscal commissions, and the like as key vehicles to suppress our freedoms and choice of legislative environment in which we live.

Conclusion

These so-called “free trade” agreements are nothing more than a further destruction of the democratic freedoms that the advanced nations have enjoyed and cripple the respective states’ abilities to oversee independent policy structures that are designed to advance the well-being of the population.

The underlying assumption is that international capital is to be prioritised and if the state legislature compromises that priority then the latter has to give way.

This is truly a ‘dark age’ we are living through.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

‘Freedom to’ is in essence always ‘power to’.

Krugman, on June 29 in Greece Over the Brink, has advocated that the Greeks exit the Euro for reasons similar, though not identical, to yours, Bill. In addition, he contends, without qualification, at the beginning of his article, that the creation of the Euro was a bad mistake. Alexandre Lamfalussy, an architect of the Euro who, at the time of its creation, emphasized that the creation of a unified currency in the absence of a unified polity was a mistake. And so it has proved. I read Lamfalussy’s view as being that the Euro as constructed was misconceived, not that it was an error full stop. This makes me view Krugman’s contention as essentially lacking in nuance. And not for the first time.

Bill, you know this but some of your readers may not. And it is this. Members of Congress, whom you might have expected to have complete access to documents that they are being asked to pass into legislation would be able to inspect said document. But so secret has been the shenanigans surrounding these two treaties, one for Europe and one for Asia, that only certain members of Congress have been given access to the documents, which they must read in a certain site, can not copy, and can not discuss with anyone. At one point, there was an implied threat that do discuss the treaties with anyone could be construed as an act of treason. This may well be hype hyped up by critics, but the process as a whole is indicative of the authoritarian manner in which this entire situation has developed. It has become clear to critics in the US that these treaties are not even good for the working people of the country whose treaties they are. Hence, the administration has experienced difficulties in getting them passed through the various hurdles. A lot of arm twisting appears to have been going on — in secret, of course.

As you have noted, these treaties benefit only US corporations and only the large ones at that. Everyone else gets shafted. Obama has described these treaties as being indicative of the way international trade will be conducted in the future. if so, the US will be leaving democracy behind and embracing a new variant of authoritarianism.

The more I read of Bill’s insight, today, the more I thought of the movie “Rollerball”….a futuristic fable about corporate take over of the world…a must see if you missed it.

“This is truly a” dark age” we are living through”. Perhaps some light has just begun to illuminate an ugly reality as it has existed all along? Were the years of progressive measures just taking us down a path leading to where we have arrived today; a neccessary step to thouroughly embed the illusion that elite totalitarianism by corporationism is good for the world?

An author once wrote that “a dog does know he is on a leash until he tries to exeed it’s length”. Western “democracies” may be about to discover how long their leash is.

Sorry re my comment above: that last quote should read ” a dog does NOT know he is on a leash until he tries to exceed it’s length”.

International trade should be undertaken only were there is mutual benefit to the trading partners by way of each obtaining something they could not otherwise obtain by a reasonable effort using their own resources while striving for maximal productivity.

The concept of camparative advantage when used strictly in the context of profit maximization is the corporate tool used to justify trade agreements which allow them to simply game/exploit all markets strictly for corporate profitability, as corporations are mandated to do. There is no way this benefits anyone exept the major investors.

Trade should be undertaken for the benefit of real people, in the spirit of international cooperation. Either the corporate mandate needs to be changed to reflect this or global trade must be regulated by the trading nations in such a way as to ensure maximum mutual benefits to their populations in terms of delivering real goods.

Thanks for saying this, Bill.

Regardless of how one views the THEORY of free trade, the reality on the ground is that the working class has been handed a raw deal. In practice, trade agreements are for the benefit of the elites, not for the benefit of the working class.

Not to justify the TPP in anyway but one thing that I did see mentioned but doesn’t get widespread mention is that Obama wants to get the TPP passed out of fear that China will lock other countries into its own Trade agreement instead. This seems to me to be how the corporations have made Obama so motivated to get it passed. How and why this could be considered real blows my mind. Why would any country sign up to such dodgy secret deals with anyone including the USA let alone China. I really do wonder how much money Obama will get from these companies once he is out of office. Could it be as simple as follow the money? Sadly it smells like it probably is that simple.

… and in the end, thanks to the Free Trade Agreements, a small company in Adelaide marketing statues of Dalai Lama will be able to sue the Standing Committee of the Central Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China – and win.

Or not.

Google for:

“Witness – In Memoriam: The man who sued the KGB” Reuters.

“A couple of years after leaving Moscow for a new assignment in Germany, I heard that Viktor had died in prison, of pneumonia.”

Neoliberal capitalism itself, among many other things including the NSA, has been already hacked by the Chinese.

This is certainly a welcome article. From a PK perspective the trade theory aspect of “Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy” looks a lot Adam Smith’s absolute advantage. This perception is made worse by some strong statements to the effect that it doesn’t matter if a country has a current account deficit.

Adam Smith’s logic reasons that if trade is good between individuals then it must be good between nations. Therefore without even resorting to any Keynesian logic, the logic of Marx to trade between individuals already applies. Trade is never on an equal basis. Capitalists tend to trade for profit and workers tend to trade for subsistence. The PK application of this logic at an international level is that the level of development of a country matters in international trade. A less developed country is less capitalistic. The less developed countries tend to trade by necessity whereas the more developed countries tend trade for profit.

Keynes’s criticisms of free trade were aimed squarely at Ricardian comparative advantage within the classical school and this argument applies to a greater and lesser extent across most Keynesian thought, even for some of the New Keynesians. Keynes was weakly opposed to free trade because trade theory wasn’t central to his arguments. Keynes was opposed to free trade because it relied on the logic of Say’s law and equilibrium.

Among the old Keynesians, Joan Robinson was the most vocal in opposition to free trade. She despised the injustice of free trade and rightly so. Free trade was responsible for major famines within the British empire. Free trade agreements make it impossible for poor countries to adopt pro development policies. The advantages of free trade tend to be cumulative and therefore compound the benefit for richer countries.

Kaldor’s analysis looks at the effect of trade on the technical growth rate. In Kaldor’s view technical growth is determined by the size of a market. The bigger the market, the greater the technical growth rate. Therefore using Kaldor’s analysis, Asia has achieved rapid technological development by using western markets to improve its technical growth rate. This logic also explains why rising inequality causes lower technical growth. In the financialised model of increasing inequality, markets for produced goods are replaced by asset price inflation. This drives accumulation by the rich who are even more likely to buy non produced assets. The diminishing of markets for produced goods causes real capital shallowing and this trend pushes society towards a feudal model where private property is traded instead of produced goods.

This reasoning brings into question the usefulness of MMT sectoral balance identities. These blogs have a lot of static balances. Keynes used discrete calculus notation and I haven’t yet seen an explanation of why. My opinion is that he didn’t want to advocate a new formalism but wanted to acknowledge the discrete nature of financial transactions in his explanations. Many PKs have instead adopted the non linear approach. This is a debate for the future and these three options aren’t the only potential formal models.

Asia is currently at a crossroads between neoliberal capture by its own elites and maintaining its prosperity by creating a more equal society and boosting its domestic demand. There are some similarities here to the cold war. During the cold war, the western elites used democracy and economic justice to boost the western technical growth rates. The collapse of the Soviet Union meant that western elites no longer needed or cared for western solidarity. This led to the subsequent impoverishment of the west by the western financial sector. It’s not yet clear how trade with Asia will unfold but the TPP is an attempt to create a world elite in opposition to workers.

All the flags and the fear-mongering over terrorists and refugees by this government is deliberate. It is expressly and cynically designed to distract the media and consequently the public from giving sufficient scrutiny to the government and its relationship with financial and corporate interests.

If Abbot parades in front of enough flags and says ‘death cult’ enough times then perhaps we won’t notice their treasonous behaviour in signing Australia up to this agreement at the behest of global corporations?

Hackey, Keynes used the difference calculus because he believed that, at the level of development of macroeconomics in his time, this was all that could be justified. Since then, many other approaches have been advocated. But the complex mathematics common in the neoclassical school is nonsensical and has no relation to reality.

Keynes would have agreed that economic interactions are non-linear, and he even said so.

I may be misunderstanding what you are saying, but I do not observe any *inherent* static characteristics in the sectoral balances approach. If you have a look at Stephanie Kelton’s What Happens When the Government Tightens Its Belt, you will come across a teeter-totter, which, it seems to me, is a dynamic analogy of sectoral balances analysis.

larry

The differential calculus approach describes flows. In the case of economics this is just a metaphor not an underlying implementation. However, it’s clearly better than a classical equilibrium model. Keynes used a previous-state notation. These are for state transitions in sequential equations.

My view is that the saving interpretation of underconsumption is wrong and that saving is really a time preference. This preference is for the length of time people wish to defer consumption. At the moment I’m not sure how this can be modelled.

In my view the value of mathematical modelling should certainly be downplayed. I will read the Stephanie Kelton piece before I make any more comments.

Hackey, you and I are in complete agreement about the classical equilibrium “model”, or as I prefer to call it, theory. If I understand Bill right, he doesn’t care for it either. Kelton’s piece is in the New Economic Perspectives blog. Offhand, I can’t give you the date, but if you go to the site and click on her, you should be able to easily find it. Good luck.

I read the two Stephanie Kelton articles. I don’t disagree with anything that she has said. What I’m questioning is how useful this information is. In order to detect a trade imbalance or an asset bubble you would need to be able to detect a shift away from domestic production. Is it practical to measure the quantity of production? Production in a modern economy is not material stuff, it is information. Although it’s possible to measure information, this is not practical at a macro economic level. Therefore the spending figures for a sector don’t tell you whether there’s been an improvement in productivity or a decline in output. Either could account for lower spending.

As an example of what I mean; you could create a control system around the see-saw model in Stephanie’s article. The problem isn’t building the control system, the problem is deciding what you want to achieve with it. How can you tell what’s good and bad in that model? To an extent you can tell what’s bad because any rapid change in a system is generally bad, but the solutions required are probably ad hoc.

Bill is quite big on econometrics and is very skilled at it but there are great difficulties in measuring an economy. When we are trying to measure we have a choice between direct and indirect measures. Sectoral accounts are direct measures, but they’re not direct measures of whether the economy is doing well. For this there are no direct measures and we need indirect measures. As we can’t measure the amount of information produced by an economy directly, we have to use prices as an indirect measure of the quantity. Now it gets hard because this leads to traps of circularity.

I think you may be making a mountain out of a molehill. You can certainly keep track of asset prices and if you see them traveling upwards without any corresponding upward movement in the productive sector, you can feel reasonably sure that you are in the presence of a bubble. Then, if history is any guide and you believe Kindleberger and Bill Black, you can also be reasonably sure that behind this asset bubble is a good deal of fraud. It seems to me to be basically a correlation exercise within a causal explanatory theory. If you are careful, it is possible to avoid circularity. A number of heterodox economists predicted the current GFC many years before it took place, though not necessarily its size or breadth. But part of the severity of this GFC and the lack of recovery, as with the one in 1929/1933, are primarily the consequence of the inept political responses to them — to wit, the implementation of austerity measures, pro-cyclical in both cases, rather than countercyclical ones. The Eurozone has additional issues not found in other places.

That said, I am not saying it is easy, only that is eminently possible and additionally possible to avoid the specter of circularity if one is careful. After all, in this case, it was done, which constitutes empirical evidence it can be done. And the economists who predicted the crisis did it with the empirical evidence they had to hand, their minds unshackled by ridiculous and empirically false presuppositions about the character of the system they were investigating.

The mathematical modelling we can do mostly doesn’t work. The classical equilibrium model is a total failure because that type of model is for non living processes. Virtually everything from the classical school is broken. Complexity theory suggests the impossibility of optimisation. Rational agent microfoundations theory needs independence which doesn’t exist.

Unfortunately the non linear models also diverge strongly from empirical data. If you look at the disaggregated data there are widespread category errors for things like investment, saving and capital. One of the problems here is accounting because these real aspects are more like vectors or classes instead of scalars. Then there’s the effect of non capitalist activity which isn’t accounted for. My view is that there is a large but declining non capitalist sector.

There are some basic arguments on causality that seem correct, e.g. aggregate demand deficiency, endogenous money, monetary theory of production, endogenous business cycle, non independence of parameters. However these arguments break the mathematical models at fairly basic theoretical levels. This leaves ad hoc reasoning which is where institutionalism has always lived.

We can see the equivalent of the asset bubble in wages. Wages in the west are in long term decline. Depending which datasets you use you can track the trend back for a minimum of 15 years and a maximum of 45 years. I don’t think theory tells us much about what steps we should be taking to address this. The government should be spending money but on what. Round here people would suggest the job guarantee and traditionally people would say infrastructure. If we actually knew what we were doing then we could say, for example, the effect of different policy options on technical progress.

I’m not the only person with doubts about basic theory. J. K. Galbraith, Kaldor and Minsky spring to mind. I understand the mountain out of a molehill argument because reasoning still exists and it’s always possible to do something. However, try comparing the effectiveness of models in economics with the effectiveness of models in engineering. This will illustrate how broken economics is.

I think we are in basic agreement about the mathematics. It is my position that MMT is the best worked out alternative to the neoclassical paradigm and its greatest strength is that it cleaves closely to empirical description without trying to fly too high into the theoretical stratosphere. The discipline isn’t ready for that, though the field needs some theoretical structure — data is never theory free.

As for basing macroecon on micro foundations, which neoclassical proponents advocate, this comes from their physics envy, a ridiculous position whose manifest failures they seem unable to learn from. I agree that if you compare the successful applications of mathematics in engineering with that of neoclassical economics, engineering beats it hands down. But I would expect that, as the theoretical presuppositions that neoclassical proponents make are empirically absurd, thereby rendering their mathematical exercises scientifically otiose, as you note (Bill has also pointed this out a number of times.).

At the present degree of development of economic theorizing, economic analysis and its relationship to policy questions needs to pay close attention, I think, to what has worked in the past. And for that, we can’t do better than consider which of Roosevelt’s experiments worked during the Great Depression. During that period, ignoring the blip in 1937 when Roosevelt briefly lost his nerve, we can see that R’s job guarantee scheme and the concentration on infrastructure of all kinds worked reasonably well. It would have worked better had more money been put into the schemes, which I think we can reasonably infer from the consequences of the preparations for WW2, which began in the late ’30s — unemployment was around 2-3% if I am not misremembering what I have read.

Neoclassical economics was broken from its very beginning, but MMT can I believe take up the baton, if I may put it like that.

‘The make-up of the tribunals is beyond the discretion of a nation’s population and, as far as we know, will be heavily weighted under the TPP by the corporate lawyers and other nominees’

Just 15 of these arbitrators have sat on 55% of the known cases decided so far:

http://corporateeurope.org/trade/2012/11/chapter-4-who-guards-guardians-conflicting-interests-investment-arbitrators

There is a clever little graphic to show how cosy it all is.

A comment by an arbitrator not on that list is illuminating:

‘When I wake up at night and think about arbitration, it never ceases to amaze me that sovereign states have agreed to investment arbitration at all […] Three private individuals are entrusted with the power to review, without any restriction or appeal procedure, all actions of the government, all decisions of the courts, and all laws and regulations emanating from parliament.’

Juan Fernández-Armesto, arbitrator from Spain

‘The APC can hardly be described as anything other than a pro-market body.’

That’s a worry then. This is from the Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade:

5.57 The committee recommends that National Interest Analyses (NIAs) be prepared by an independent body such as the Productivity Commission and, wherever possible, presented to the government before an agreement is authorised by cabinet for signature. NIAs should be comprehensive and address specifically the foreseeable environmental, health and human rights effects of a treaty.

http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/Treaty-making_process/Report/b02

As I said in my latest missive to my local members Malcolm Turnbull and Bruce Notley-Smith (the last one nearly 3 weeks ago is so far unanswered) –

‘ I am aware that there’s been talk of having NIAs (National Interest Assessments) conducted for contentious elements, with ‘independent’ bodies such as the Productivity Commission invited to participate, but any public body with that weight of capital riding on its shoulders will not remain independent for long.’

larry

I’ve had to rush some of the posts due to lack of time and I’m not sure all of the points I’ve made are clear and some may not make sense. Having had time to think about this, I think I can summarise the main point I am making.

MMT is about macro reality. In this area of theory I think it’s probably a bit better than other PK horizontalists. The problem comes when this strays into macro-foundations logic. PK has its own micro economics. The main reason that micro cannot be aggregated is because PK micro explanations don’t use scalar types. Mark up pricing is a well known example of PK micro but PK consumer theory is a more useful example. Consumers allocate their income to categories such as subsistence, treats for children, holiday, etc. and then rank items of expenditure. The categories are ranked and the expenditure within the categories is ranked. Therefore the data structure at this level is a list of lists and ordinals can’t be aggregated. If I went into more detail I could perhaps describe the items of expenditure as a schema with properties other than cost and utility, for example uncertainty and time preference. Therefore causality from macro to micro goes through channel switching processes such that macro logic no longer applies when you get to micro level.

Investment at a macro level is a scalar accounting measure but this is not the same as investment at a micro level. The transformation is a channel switching network as causality runs from scalar to multi dimensional vector to domain specific data structures. The specific processes of MTP transmission make it impossible to model. There’s a similar network of switching apparatus to go from micro to macro as the causality is circular.

I can’t make a strong statement about this without reviewing a lot of literature, but my feeling is that MMT allows macro reasoning into the space of micro economics. In the case of sectoral balances I’m not opposed to the sectoral approach in general but I don’t like some of the applications. At a macro level I see saving as an emergent property of accounting. At a micro level I see it as a decision not so consume. Some people also equate savings with surplus. Macro savings, Micro savings and surplus are completely different. Macro savings result from income that isn’t spent. Micro savings could be buying gold to bury in the garden (which ultimately would be digging up gold in order to bury it in order to be able to dig it up again). Surplus is output in excess of replacement. This confusion is partly a legacy of Keynes but he tied these concepts in with capital theory and I don’t think MMT does that.

Hackey, I agree with your distinction among micro and macro saving and surpluses. Anyone who conflates these does not know what they are doing. And there are issues of data scaling between the micro and macro levels. The scale types themselves should be integrable, but I think the problem of merging micro and macro econ is problematic, it seems to me, at an even deeper level. In addition to issues of data analysis, there are conceptual problems. We find difficulties of integration with quantum theory and general relativity, and they are much more developed conceptual schemes than the ones we are dealing with, but they are able to trundle along relatively amicably.

As for the channel switching analogy, I do not think I am able to comment on it, as I am not familiar with this way of looking at the problem.

larry,

We both seem to agree that neoclassical economics is completely broken. We both seem to agree that there are problems with all theories including PK ones.

In Ricardo’s initial conception, classical economics was a theory of real commodities. The theory of value was created in an attempt to apply it to a capitalist system that uses money. Within Marxism this led to the transformation problem. Keynes rejected the theory of value but did not invent a completely new form of economics. He built on underconsumption theory which is based on the rejection of Say’s law, paradox of thrift and monetary production.

The classical school is still based on value theory and monetary saving is equated with value. If you do your job quicker and have an extra hour a day to improve your capital stock then saving is logically prior to investment. In a monetary system, money is used as a signal to produce capital goods therefore spending is logically prior to investment. There is no capitalist investment unless someone pays for it. If you reduce your expenditure and hoard cash then you are signalling that production should be reduced but this isn’t how most people save. Most people save by purchasing assets which can be held. If production was perfectly elastic then asset bubbles couldn’t happen and the only option for saving would be real capital or hoarding. Due to institutional and real factors, many assets are not easily produced. Therefore it’s possible to save by purchasing non producible assets which are likely to be in demand for a long time, but this creates an asset bubble. Lack of aggregate demand for produced goods is caused by investment substitution and this accelerates due to positive feedback effects until there is a crash.

Money is not value. It’s more like a Kanban card.

My initial points were that I am sceptical of the concepts of investment, consumption and saving in macro identities. I think macro saving should be given a different name and the meaning clarified. I think investment and consumption aren’t meaningful in national balances. Some other PK schools are using stocks/flows/sinks/sources in dynamic models which isn’t necessarily better but they are also defining sectors in a different way (e.g. more emphasis on the financial sector). More generally, I think fiscal policy discussions should use micro concepts at least half of the time and the distinction between the two should always be clear.

That’s a lot more than I had planned to say.

My micro model is a heterogeneous information network. These are used in sociology so you may have come across them there. In this context money should serve the purpose of controlling resource use but at a practical level it doesn’t do this in an equitable or efficient way. This is partly due to inequities/inefficiencies in the monetary system but also the legal system as well. At a measurement level this model is problematic because we currently only have the skill to measure encoded information and not materialised information, e.g. we know how to measure information in DNA but not a fully grown human. As well as this theoretical problem, it’s also not currently practical to have a macro information model.

Did you ever post any structuralist sociology of change? The only structuralist change theory I’ve heard of is the synthesis tradition but I think you may have seen some others.

What are the chances of stopping this deal

larry

I think it’s theoretically possible to use “science and technology studies” (STS) heterogeneous networks in combination with Shannon channels to produce a micro materialist mathematical model of entropy. It could not be predictive but it might be descriptive. There might be some implications for topological efficiency. The maths would be graph theory and statistics, which is computer science territory.