I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Time to expand public service employment

Back in 2010, in the early days of the GFC, the then Australian Labor government was weathering a conservative storm for daring to introduce a large-scale (and rapid) fiscal stimulus. The package had several components but the most controversial were the decision to introduce a homeinsulation program to create jobs quickly but leave a residual of green benefits (lower energy use in the future). The program had problems but still produced fantastic macroeconomic benefits. It was little wonder that the program stumbled operationally given its complexity and the degraded capacity of the Federal public service, which has been degraded by several decades of employment cuts and restructures under the neo-liberal guise of improving ‘efficiency’. However, that mantra might be finally turning. An article in the right-wing Australian Financial Review (June 14, 2015) – Time to end outsourcing and rebuild the public service – made the extraordinary argument for that publication that public service employment had to increase to allow the government to do what the Federal Communications Minister calls “the legitimate work of the public service”. Wonders never cease.

High and persistent unemployment has pervaded almost every OECD country since the mid-1970s. The rising unemployment began with the rapid inflation of the mid- 1970s. The inflation left an indelible impression on policy-makers who became captives of the resurgent new labour economics and its macroeconomic counterpart, Monetarism.

The goal of low inflation led to excessively restrictive fiscal and monetary policy stances by most OECD governments driven by the now-entrenched ‘budget deficit fetishism’.

The combined effects of tight monetary policy and restricted fiscal policy led to GDP growth in most OECD countries being generally below that necessary to absorb the growth in the labor force in combination with rising labor productivity.

In the fifty years since the end of World War II, most OECD economies have gone from a situation where the respective governments ensured there were enough jobs to maintain full employment to a state where the same governments use unemployment to control inflation.

A major aspect of the abandonment of full employment in these economies has been the changes that have occurred in public sector employment. Many economies have undergone substantial restructuring of their public sectors with significant employment losses being endured.

The Australian experience exemplifies this.

A Royal Commission on Australian Government Administration was announced in 1974 and delivered its – Final Report (Caution – big file).

It was commissioned by a Labor federal government and completed after they had lost office. The conservatives who took power in 1975 largely disregarded the intent of the report, which was to improve the deliver of public services. Instead, they used it to change the emphasis of the service away from “administration” towards “management” (Source).

This government was part of the neo-liberal resurgence, which attacked the notion of public activity and the concept of public service.

The first volleys were about ‘efficiency’ and ‘waste’ and as this agenda gathered pace, there was an increased hollowing out of the public service employment structure (towards executives), decreased permanency and increased contract employment, functions outsourced to private providers (mostly with disastrous consequences), increased political control over the key departmental staff, and the rise of a new breed of private consultants who do the government’s dirty work by producing on demand (for very lucrative rewards) reports that seemed to ratify what the neo-liberals wanted.

The big shifts started with the massive privatisations that occurred, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s. Some of the declines in public sector employment were in fact transfers to the private sector.

Politicians at the time claimed there would be no net job losses as a result but those claims were proven to be lies almost immediately. The privatised services shed labour and failed, in general, to offer more effective service delivery.

The second wave of attacks came just after the 1991 recession, which was the largest downturn in Australia since the 1930s Great Depression.

Even previously progressive ‘Labor-type’ parties got behind this agenda. In Britain, we saw the rise of the ‘Third Way’, which soon became part of the Australian narrative too.

This approach was a loose array of proposals bundled together into a ‘solution package’ that purported to be able to steer a route through what is positioned as the extremes of Keynesianism (regulation) and neo-liberal (free market) economics.

It was argued that government fiscal and monetary policy was impotent, and that individuals have to be empowered with appropriate market-based incentives. Accordingly, the third way solution package locates the key to the ‘problem’ of dependency within the aspirations of individuals in local communities, largely detached from the state and certainly detached from the macroeconomy.

In doing so, and by default, microeconomic market solutions were proposed to what were and will always be macroeconomic problems. Mass unemployment is never a micro issue – it is always an inadequacy of spending.

But in taking this route, the Third Way assumptions were indistinguishable from the neo-liberal approach and were soon bundled up within it with Labor-type Parties arguing for fiscal surpluses and austerity – just milder and allegedly fairer.

But there can never be anything fair about unemployment or depriving the disadvantaged of essential public services.

The result was that a promotion of both corporate and not-for-profit commercial behaviour to achieve social objectives that were previously the responsibility of the public service.

A whole host of shonky ideas came under the innovative sounding banner of social entrepreneurship. Please read my blog – Social entrepreneurship … another neo-liberal denial – for more discussion on this point.

The essential point was that Third way exponents accepted the neo-liberal notion (based on the erroneous fiscal austerity view) that welfare and other services need to be delivered more ‘efficiently’, and from this premise advanced another, that entrepreneurially generated profits via full-blown business activities were required to cross-subsidise welfare provision in an era where budget allocations are highly constrained.

The Third Way literature introduced the concept of the ‘overloaded government’ which was a central neo-liberal idea – that government was too big, weakened by the burgeoning requirements of policy incrementalism, and experiencing crises of legitimacy because of its apparent inability to effectively manage and fund these responsibilities.

It was largely an agenda based on lies and deceptions but it was marketed very effectively by the burgeoning number of ‘think tanks’ which were being funded by conservative corporations and individuals to advance the narrow agenda of these entities.

As the public service was attacked and diminished in size with essential services being out-sourced or privatised, its function shifted to contract management. It was argued that public accountability would be maintained through the contract mechanism to control contract agent behaviour.

So the public service became dominated by ‘contract managers’ rather than experts in program delivery.

An extensive literature has emerged since then to reveal significant imperfections in Australian accountability regimes between public sector funding bodies and funded private organisations.

The decline in public service employment

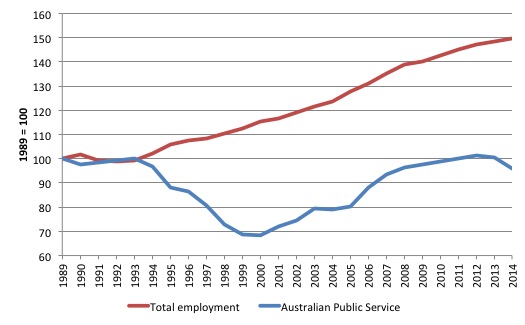

The following graph shows the evolution of Australian public service employment since 1989 indexed at 100 in 1989 (blue line). The red line is total employment in the economy as a whole which has grown about the same pace as the Labour Force (with cyclical deviations).

The Labor government was in power from 1983 to 1996, and it was this regime that accelerated the degradation of the public service. When the conservatives (Howard) was elected in 1996, he initially hacked into public service employment but reversed the decline.

The next Labor government, elected in 2007 moderated the growth rate in public service employment but when they lost office, the new Conservative Abbott government has returned to its DNA and started to savagely cut again.

Over this time, public service employment has gone from 2.2 per cent of total employment in 1989 to 1.4 per cent in 2014 (and declining). To put that in perspective, total Commonwealth employment in 1970 was 6.1 per cent of total employment.

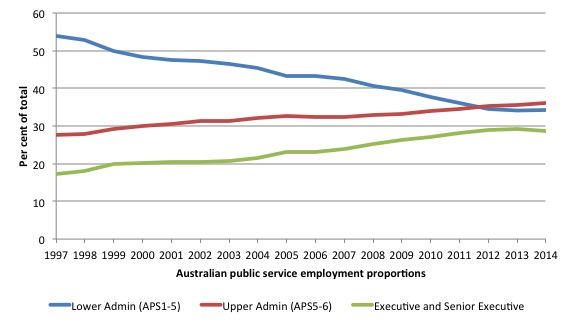

The other aspect worth noting is the change in the internal structure of public sector employment in Australia over this time.

The following graph shows the proportions of the different hierarchical divisions in total public service employment. The date prior to 1997 is not commensurate with the later data given changes in classifications and presentation. But the trends shown in the graph were present from the late 1980s as the neo-liberal shift to managerial control and administration of outsourced contracted began in earnest.

These trends were consistent with the shift in functions towards contract management noted above.

Why does this matter?

There were clearly issues with the implementation of the two big stimulus packages that the Australian government introduced.

Some parts of the stimulus intervention (a relatively minor proportion of total funds spent) were problematic in terms of administrative issues.

The – Energy Efficient Homes Package – was highly problematic in a number of ways notwithstanding the macroeconomic benefits it brought – income and employment growth etc.

Remember that Australia did not have an official recession during the GFC, which set it apart from most advanced nations.

The program was delivered by private contractors and a spate of rather dubious operators entered the field to cash in on the contracts on offer.

However, the latest estimates are that it “covered 1.2 million homes and it has been estimated that by 2015 it will have produced savings of approximately 20,000 gigawatt-hours (72,000 TJ) of electricity and 25 petajoules (6.9×109 kWh) of natural gas savings”.

But, four workers died installing the insulation while the program ran, which raised questions of whether the Government was cogniscant of the risks involved and did enough to prevent the deaths.

The Australian National Audit Office investigated the implementation of the program and in its – Performance Audit Report – published in October 2010, it concluded that:

1. The program “was designed to generate economic stimulus and jobs for lower skilled workers in the housing and construction industry, which was expected to be adversely affected by an economic downturn flowing from the global financial crisis.”

2. “The program was developed in a very short period of time between 3 February 2009 and 30 June 2009 as a stimulus measure to respond to the global financial crisis.”

3. “The focus by the department on the stimulus objective overrode risk management practices that should have been expected given the inherent program risks. Rather, the department intended to rely heavily on its compliance and audit program to address some of the risks identified, but the significant delay in implementing this element of the program meant that these risks were not adequately addressed.”

4. Most importantly:

There were insufficient measures to deliver quality installations and, when the volume of issues requiring attention by the department increased, the department had neither the systems nor capacity to deal with this effectively. The lack of experience within DEWHA in project management and in implementing a program of this kind were contributing factors …

The fallout from the program has … harmed the reputation of the Australian Public Service for effective service delivery. This experience underlines very starkly just how critical sound program design and implementation practices are to achieving policy outcomes. There are important lessons here for those agencies with policy implementation responsibilities but also those responsible for policy development.

So despite the clear macroeconomic benefits including many thousands of jobs saved the program highlighted major deficiencies in the capacity of the public service to deliver complex stimulus programs without significant problems.

However, we also have to remember that large-scale stimulus interventions of the type taken by the Australian Government – which in international terms was early and large relative to GDP – are very complicated and you can expect some administrative inefficiencies.

Imagine if the private sector had to ramp up investment spending within a quarter or so to the levels that saved the economy from the GFC – what do you think would be the outcome of those projects.

But we also have to understand the context that the program was introduced. As noted above, the neo-liberal era has been marked by a major reduction in Departmental capacity to design and implement fiscal policy – given the obsession with monetary policy and the major outsourcing of ‘fiscal-type’ government services to the private sector.

Many of the major Federal government policy departments are now just contract managers for outsourced service delivery. So with the voluntary reduction in ‘fiscal space’ (defined as capacity to use real resources productively) within the federal government over the last 20 years or more it is no surprise that the overall capacity of the government machine to implement efficiently and speedily complicated nation-wide infrastructure programs has been diminished.

At the time, I gave several media interviews noting that these shortcomings were a lesson for the future.

The GFC taught us that we can no longer deny that fiscal policy is required to address serious swings in private spending which if left to their own will cause major recessions.

Monetary policy has been proven – categorically – to be ineffective in dealing with aggregate demand failures of the sort we have witnessed in the current crisis.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) teaches us that the currency-issuing government has an infinite capacity to purchase resources that are for sale in its own currency. There are no financial constraints.

But to be effective, the same government must be able to bring those resources into productive use to the benefit of all, especially at times when the private sector demand for productive resources is weak.

In that context, governments must develop forward-looking capacity to ensure that it has project implementation skills when they are required.

Clearly, if we had left the GFC to the Chicago school (or the Harvard school) line – which means government would have sat back and left it to the private market to sort the mess out, then we would have been facing a repeat of the Great Depression such was the damage to the financial system and the plunge in real output in the major economies.

At the time the stimulus packages were designed and announced, the Australian Labor government believed we were on the precipice of another Great Depression. The international events demonstrate that the crisis has been very severe. So the government rightly assumed that there would be major idle labour skills available to be brought back into productive work. That was a reasonable assumption and the fact that the downturn hasn’t been as bad as that demonstrates that the fiscal stimulus has been very effective.

However, the lesson from the home insulation package is that forward-planning is necessary and the public service cannot just be a contract manager. It has to have in-house skills in project evaluation and design and operational capacity to deliver these programs.

Which means it has to return to the past practice and stop outsourcing everything to consultants etc.

Which brings me to the article in the Financial Review that I cited in the introduction.

It argues that the neo-liberal period has led us to believe that the answer to maintaining a productive economy :

… was to bring business and its practices into the public sector: by contracting out jobs, from road construction to the provision of highly skilled advice and other services; by opening departments to modern management practices and accountability; and by “corporatising” or, better still, privatising government businesses.

But now we realise that this has been myopic thinking and the damage it has cause the public service needs to be reversed immediately.

The author (not known for progressive views) notes the Federal “Communications Minister … lamented last week the brain drain from the federal bureaucracy as governments have turned increasingly to private consultants.”

The Minister said last week that:

There has been a practice for government to outsource what should be the legitimate work of the public service to consultants … So the public service departments just become, you know, mail boxes for sending out tenders and then receiving the reports and paying for them.

The public service has been so attacked and downgraded that it now lacks staff “with the necessary quantitative and analytical skills” and that the host of consultants now relied on by governments are of “varied quality” and may not have “motives” that align with government ambitions.

Certainly, there are countless cases where consultant reports propose solutions that are not at all in the interests of the general society but feather the nest for one elite group or another.

The author notes that there are “consultants who cut corners, provided superficial reports and second-guessed what ministers wanted to hear.”

In other words, government programs are being captured by a narrow group of private consultants whose interests often are only their own advancement and wealth generation.

A familiar tale across the advanced and less developed world.

The Minister of Communications said in this regard that:

… there has been a practice for government in particular to outsource what should be the legitimate work of the public service to consultants.

What we have to do in government in my view is stop panning public servants and do more to ensure that they do their job better. And one of the ways to do that is to make sure they do the work that is their core responsibility, as opposed to outsourcing everything …

The talent is the real asset of the Australian Public Service, so we have got to have a focus on the APS, a respect for the quality and seek to promote and improve the quality of that workforce all the time.

And it will require the Government investing some serious funds in rebuilding the employment base of the Australian Public Service. It should start by rebalancing the occupational structure away from these senior managers who take more than they are worth by far out of the system at the expense of recruiting skilled operatives that can actually design and implement government programs.

It will require the Government to abandon its competitive education model and refund public training and skills development within the public sector.

It will require the Government to once again become a more significant employer in its own right.

Conclusion

The thing that was surprising was that these ideas were rehearsed by a journalist who usually promotes an anti-government line. Some of the article continued that theme but the message was clear – it is time to restore some expertise in a the public service in Australia to ensure that big programs that are essential for Australia’s well-being are not put in the hands of second-rate and greedy private consultants.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

That is good news, for sure. Let’s see if either political mainstream party gets the message.

It’s vital that there be forward plans.

When the US New Deal was being set up , the only shovel ready works were the parks service projects. They gave the US an outstanding parks environment still valued today, even though neglect is having its effect.

I agree the insulation scheme was a sterling effort, but as you say less well run than if the public service was properly staffed and funded. MMT shows funding problems are purely political in nature. This mindset needs reversing.

A useful plan would be how to manage the inevitable existential crisis that we cannot avoid. As we continue through excessive waste and delusional belief in BAU for ever, we will urgently need to have plans ready to manage the economy and essential services. MMT can make a difference here.

Agreed. But most people hate the public service. Recall the attacks on Greece with its “lazy public servants” etc.

The idea that the public sector should take a bigger share of GDP is a purely political idea. That “size of public sector” point is the basic difference between political left and political right. So economists should not discuss that point while wearing their economist’s hat.

Moreover, I fail to see why employment would be any higher with large public sector than a small one. Full employment (on any definition of the phrase you choose) is as easy or hard to attain when public spending takes 20% of GDP as compared to when it takes 40%.

As for the idea that a decent JG system is public sector, therefor to that extent a bigger public sector raises numbers employed, that argument is flawed. Reason is that one can have private sector JG jobs.

Of course some people object to private sector JG just as they object to private education, health care, etc. But that again is a purely political point.

Its purely a mechanical and functionality idea. You can frame the word ‘efficiency’ in any context.

Eg: In computer science: algorithmic solutions ‘efficiency’ is important as time-to-compute efficiency or space-to-compute efficiency. Often the two are inversely proportional.

In a complex system like a country there are plethora of feedbacks efficiency in one defined domain will be an inefficiency in others.

At a certain point for solving an instance of a problem there is a cut off where you invariably loose functionality. By reducing the public sector workforce below a threshold you get disasters.

The 2013 downward sloping curve in the public sector graph does not surprise me:

One of the first things the current Australian ‘government’ did in office was sack >16500 public servants. It did so by appointing the Business Council of Australia to a “Commission of Audit” into what could be cut.

None of the governments antics have anything to do with ‘efficiency’. Outcomes are not measured by aimable goals like “functional finance” meaning that public policy should be judged by its results in the real world employment, productivity and price stability and not by whatever may be happening to budget and government sector ‘debt’.

“The idea that the public sector should take a bigger share of GDP is a purely political idea. ”

Totally agreed Ralph (well disagreed, as I want a larger public sector) 😉

Ralph,

Are you also opposed to the crowding in model? For example, in Germany the government crowds the SME sector into capital intensive production using its state owned development bank. On the other hand, the German private banking sector bought US CDO junk until it was insolvent and then blackmailed the state into banking bailouts. When the state makes decisions based on inherent factors then it doesn’t need to be efficient because the private sector makes decisions based on one factor only, i.e. profit.

Ralph,

While most of my objections to your scheme are ideological (business shouldn’t get subsidies, etc), how would you stop the problem of businesses dumping workers to ‘harvest’ subsidies under your workfare/JG style scheme?

I can see how the JG works with fixed wage JG replacing unemployed in current system, but how would the private sector JG control price inflation? What are the dynamics?

The problem is more fundamental than that, which is the way that you hire for a job.

In both the main public sector and the private sector the design is this. You come up with something to do and then search for somebody to do it. If you can’t find anybody you redesign the job structure and try again. But however you do it you are always matching a person to a job.

With a Job Guarantee the function is the opposite. You get given a person and then you have to find them something to do that is both useful to the individual and satisfactory to that individual peers as payment for the wage earned – which involves marketing the value of the work to the peer group.

So you are matching a job to a person. Completely the other way around from normal. And it is this that is the vital function to get beyond the level of employment point where the standard matching system breaks down (where you get a stock of vacancies and a stock of unemployment, but little shift in the unemployment rate).

A private sector entity cannot and will not do that within the normal operational terms that define a private sector entity. The job of a private sector entity is to improve productivity and continually shed jobs to improve the output ratio. You destroy that function by persuading private sector entities to hang on to staff.

Of course you could outsource the Job Guarantee requirement as you outsource the Work Programme requirement – but you would get the same pathetically bad results because the incentives are just not aligned.

Outsourcing has never really worked – for the fairly obvious reason that they have a huge sales, marketing and PR operation to fund that a public sector body simply doesn’t have. But because marketing works, people believe the Outsourcing PR.

We all economics is political Ralph.It is human social interactions with money tokens after all.

I am in the whatever works camp. No doubt the private sector provides much good quality stuff

and reasonably efficiently but it has its legacy of massive failures.

Just take a few.Perhaps the greatest challenge facing mankind finding a sustainable source of energy

preferably non co2 producing -massive private sector fail!Providing good quality non subsidised

private sector education ,healthcare,transport,housing for the bottom 50%-epic fail!

When you need large upfront investment with uncertain medium returns is the private

sector your go to sector?Especially if your would be customer base are monetary tokenly challenged?

Then there is that whole parasitic lets make pots of money speculating on the future price

of stuff that already exists instead of making new stuff dysfunctional financial sector

Political for sure but my vote is for Bill’s public sector expansion.It’s good economics too.

Neil the problem is there are so many incredibly important jobs that nobody is doing for

want of money tokens

A major problem for computing at the moment is the highly concurrent processing needed to meet worldwide demand that can be placed on large data stores of internet companies. This is a problem that the private sector is now looking at because there are commercial reasons for doing so. 35 years ago there were government funded projects in the UK that were making breakthroughs in the area of high concurrency but the Thatcher government decided that research was not a role of government and sold the staff and patents. It’s quite typical of research in the private sector to lag 30 years behind government research. The advances of Apple are advanced only in the sense that they can sometimes lag the public sector by a mere 15 years. The private sector is typically conservative and does not like to innovate. There are good business reasons for successful companies not to innovate because a major change can alienate customers. Being a first mover is high risk, carries high cost, the rewards are small and the successes are easily copied. The private sector has profitability constraints but a public sector justification uses logic that is specific to the problem domain.

The best model for innovation is to crowd out and crowd in at the same time. If the government employs talented people at a high wage and at the same time buys capital intensive goods and services from the private sector then both the public and private sector are aiming for a high rate of technical progress with high utilisation of real capital. The public and private sector are then competing with each other but the public sector is also acting as a market maker. Market making is one of the standard roles of government. The government must create markets where the private sector has failed, is failing and will continue to fail.

Stuart Macintyre in his book Australia’s Boldest Experiment: war and reconstruction in the 1940s (NewSouth Publishing, 2015)talks quite a bit about Lyndhurst Giblin and in 1943 Giblin noted that “the demand for job security was so strong and so general that no government could withstand it; full employment had become a ‘test of democracy'”. (p237) How far have we fallen?

Excellent points from Huffey. Research is one of the six key areas where we need to

expand public service employment alongside sustainable energy production,housing,

education,healthcare and transportation networks.

Bob,

Re your first question, the answer is to limit the time for which people do JG work at a particular employer (to roughly a couple of months) and then shift them on to another JG job or back to the dole queue. Employers don’t want to lose PRODUCTIVE but they don’t mind losing UNPRODUCTIVE ones. So that rule forces employers to classify as JG just those who are unproductive. Second, the temptation to “harvest” is not confined to the private sector: public sector employers are also under pressure to produce results, so they are tempted to harvest.

Also relatively short duration JG jobs are not a bad idea: they expose JG employees to a variety of types of work. In the case of those who are going to have to change the type of work they do, that helps them decide what type suits them.

Re your second question, I don’t think that JG in any shape or form “controls inflation”. I.e. given grossly excessive demand too much inflation is plain unavoidable. Strikes me the idea put a lot of JG supporters that JG somehow “anchors” all wages is nonsense. All JG does is to improve the inflation/unemployment trade off a bit.

Kevin Harding,

Re your idea that all economics is political, that point can be made even more general: i.e. everything is potentially political. That is, the electorate and politicians are entitled to intervene in absolutely any naturally occurring phenomenon. So my definition of “political” is: “whatever the electorate and politicians have to decided to intervene in”.

I realise that’s a bit of a circular definition (or whatever the right phrase is), but given that definition, I’m sticking to my claim that economists while wearing their economists’ hats should stick to 1, naturally occurring phenomenon, and 2 studying the effect of political interference in the latter. But they shouldn’t express views on what types of intervention we should have.

Just following some of the conversations going on here:

Re: private vs public sector JG: In my experience a number of public institutions (hospitals, universities etc) have been providing on the job training opportunities for students who often then move on to successful full time employment in either sector.

My understanding is that it is difficult to find such opportunities in the private sector. I don’t believe the federal government funds either the student or the mentoring institution (usually a provincial institution) for any of this work (usually these are informal/voluntary arrangements between colleges/universities and the mentoring institution), which would explain why the private sector has so little interest in participating. Bottom line is that the public sector mentors must work harder to support the training while also performing regular duties until the trainee is able to become helpful. There is a definite incentive to make the trainee productive as quickly as possible and the effort, again in my experience, is that these programs have merit for all parties.

The student trainee’s are definitely more employable as a result of their work experience in the public institution since they do get jobs often based on strong references from mentors.

Both training and mentoring are work and could easily be incorporated into a JG program involving any sector with either/both the student or mentor a JG program participant.

There are also many jobs in any sector which could be done and would provide valued output and are not being done simply because no one has recognized them as jobs yet or they are being done by volunteers for free. We all know that the ” invisible hand” needs money before it moves were we need it most. Without a JG to get things started this is being lost.

Arguing about productivity of workers in the JG is at any rate secondary to the main points which are to get unemployed people working at something so society at least benefits from some of their labor output, which the dole does not do, and to give participants that recent or ongoing work experience that employers seem to hold important.

If the JG is done very well, the private sector benefits by being able to shift workers without undue hardship to a JG when they are changing course and require workers with different skill sets. The workers can be aquiring through the JG skills that make them more productive and more attractive to employers of any stripe.

As for the job guarantee setting the minimum wage, I don’t see how that could be avoided. Many good workers are treated and paid poorly by inept employers (who may not have the management skills to maximize productivity from workers, or are unwilling to share some of the rewards when they do) and would be willing to move to a slightly lower paying JG job temporarily while looking for a better employer. Jobs that pay less than a living wage really aren’t jobs at all. They are instead wage slavery supported by the creation of a reserve army of unemployed people who are maintained by the entire community through the dole, food banks, housing programs etc.

Alexandrian patterns are a growing practice within software development and the method of Alexandrian patterns is the same method used by the ancient pyramid builders, to see what works in practice and build a theory around that. “Alexandrian patterns” is named after Christopher Alexander’s book, “A Pattern Language”. Although originally an architectural practice, the techniques of Alexandrian patterns are now more widely used within other disciplines. Mainstream economics often aims to adopt solutions that work in theory but not in practice. The Alexandrian pattern movement aims to document solutions that have worked in practice (if not in theory) and describe the common patterns. The economic school which is closest to Alexandrian patterns is the institutionalist school. Institutionalism would benefit from an Alexandrian pattern movement. This is one route towards developing a practice for successful policy making. It’s not a quick solution but it’s quick enough. Policy pattern catalogues could exist within twenty years.

Kevin,

Thanks. Keynes recommended a continuous shift from government revenue accounts to capital accounts but Keynes died before he had chance to see the mess that government accounts have become. The policy proposal also seems at odds with his discussion of category problems. Category problems in theory must surely translate into category problems in practice. A large portion of investment within capital accounts can be asset price inflation. If we look at the capital accounts then it might look as though there is investment, yet when we look at asset prices there’s clearly a bubble. Real capital that isn’t accounted for is also very common as well. This is why I’ve latched on to the mission oriented approach promoted by Mariana Mazzucato. It doesn’t rely on accounting definitions of capital or investment. I think in light of the evidence, Keynes and the old Keynesians would also approve of a mission oriented approach.

Couldn’t agree more Prof.

“The inflation left an indelible impression on policy-makers

who became captives of the resurgent new labour economics

and its macroeconomic counterpart, Monetarism”

Once you realise that politicians are glorified local councillors

with no personal insights, it all makes sense.

When the economic levers they had traditionally pulled

didn’t seem to work, both side of politics grasped at the

nearest available “life preserver”.

The motivation for outsourcing of public service functions

has, I believe, two main components independent of the general

Neoliberal agenda:

(i) a recognition of the lack of expertise remaining in the

hollowed out shell of what is today’s public service (6.1% to 1.4 %!)

(ii) where (i) is not the case, a desire by politicians to shift

blame to the non-elected company to whom the function has been

outsourced (eg: Metro Rail Melbourne).

If the short-sightedness of this approach is finally percolating in

the minds of the right wing, this is good news indeed.

Right wing concern with public service is fundamentally at odds with their most

cherished political believes that governments should set low taxes and run surpluses.

It is as delusional as their concern for growing inequality.Short-sightedness as in

the maximization of profits in the short term is now the driving force of the

‘free’ market which they bow before and worship. The fact that the monetarist paradigm shift

has been such a failure is not a message to which they are receptive.