I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

The skies above Britain predicted to fall down … again. Don’t fear!

You may not remember the prediction by the American Arthur Laffer in his Wall Street Journal Op Ed (June 11, 2009) – Get Ready for Inflation and Higher Interest Rates. As the US government deficit rose to meet the challenges of the spending collapse and the US Federal Reserve Bank’s balance sheet shot up as it built up bank reserves, he predicted “dire consequences … rapidly rising prices and much, much higher interest rates over the next four years or five years, and a concomitant deleterious impact on output and employment not unlike the late 1970s”. You may have forgotten that prediction because it was in a sea of similar nonsensical claims by mainstream economists locked in a sort of mass hysteria and only their erroneous textbooks to give them guidance. It is 2015, nearly six years after Laffer humiliated himself in that Op Ed. Inflation is low and falling generally. Interest rates remain very, very low (note his use of “much, much” to give his prediction some gravity). Gravity forces things to crash! But the doomsayers have learned very little it seems.

Laffer is not a stranger to self-humiliation. Remember his claim that cutting taxes would increase tax revenues – the advice he gave Ronald Reagan. It was designed to justify attacks on fiscal stimulus. The predictions then were poor.

I should add that Laffer is still humiliating himself. Last year, he was advising the Kansas Governor and the radical neo-liberal agenda imposed on that state “failed spectacularly … fell short on every possible metric, from growth to job creation to revenue” (Source).

More recently, he was in Australia as guest of the right-wing Australian Chamber of Commerce telling us that the US and Australia could increase economic growth if only they cut public spending. He also wanted major tax cuts for the highest income earners to stimulate a ‘trickle down’ effect.

Same old nonsense.

These sort of ideas persist though.

In the UK Guardian article (April 14, 2015) – ‘Timebomb’ UK economy will explode after election, says Albert Edwards – another candidate for Prediction of the Year, Not! emerged.

Albert Edwards works apparently as the head of the “global strategy team at investment bank Société Générale” and probably earns many times the value of his commentary, which is close to zero.

I am aware that if I had have said zero the mathematicians would have indicated that given the communitative property of multiplication that his income would have been zero.

The close to zero is that you might get a laugh out of his predictions, although that would indicate a pretty errant sense of humour.

The guy has ‘form’ as they say, like Laffer.

In November 2009, he predicted that the Japanese government would run out of funds within the “next year as demand for Japanese government bonds wane and bond yields rise further” (Source)

In May 2011, he wrote that “Frenzied Orgy Of Balance Sheet Debauchment” in the US and UK would precede “The Great Reset” and “rampant inflation” (Source).

And there are many examples such as this. I would say though that his views are often not the run-of-the-mill drivel that Laffer and his ilk pump out. Albert Edwards did understand that the pre-GFC period was unsustainable. He just didn’t get the reasons correct (in my view).

But in the Guardian article his attack on the Conservative government is very odd indeed.

His prediction is that:

The UK economy is a ticking time bomb set to explode after the general election … [being the] … legacy of “grotesquely wide deficits” in both the public sector finances and on the UK’s current account – its overall trading position with the rest of the world.

These deficits constitute “macro manure” which the UK economy is “up to its eyeballs in”.

And:

Eventually the stench will fill the nostrils of currency markets with the inevitable result – another sterling crisis.

His other claim (quoted by the UK Guardian) is that:

To the extent the UK economy has recovered, it is not because the public sector deficit cutting has worked as the government claim, but because, for the last three years, the government has quietly abandoned all pretense at fiscal cuts, kicking the can into the next parliament …

So what does that all mean?

First, clearly he considers the failure to cut the deficits has allowed the UK economy to recover to some “extent”. I agree completely with that view.

Please read my blogs – British fiscal statement – continues the lie about austerity and Lacklustre British economy all down to Conservative incompetence – for more discussion on this point.

It is quite obvious that the Chancellor abandoned his hard line on austerity in 2012 after the recovery he inherited started to reverse and the UK slipped back into stagnation.

This is not to say that fiscal policy in the UK has been appropriate under the Conservative government since 2010. Far from it. But the fact that the deficit has not fallen much as a per cent of GDP and it is mostly the growth in GDP that is responsible for the decline is testament to the on-going support to growth from fiscal policy.

It is simply false to claim the UK as a successful application of a ‘fiscal contraction expansion’ – the darling term of the lunatic neo-liberals.

The Chancellor has been compromised severely in maintaining the deficits – his instinct is to deliver surpluses but the reality has forced him to behave out of his skin. The result has been damaging cuts in vital services and a ridiculous housing policy that has seen private debt rise, which is holding up household spending.

The labour market has deteriorated in terms of the quality of jobs on offer and the capacity of workers to enjoy real wages growth. Productivity growth, which is the provider of rising material standards of living, has been appalling.

Please read my blog – Employment growth in the UK but of dubious quality – for more discussion on this point.

So it is a good thing that the current UK government is ‘kicking the can’ down the road, although the analogy, one of those ridiculous expressions that are common in financial market commentaries, is fairly meaningless.

If Edwards is saying that the failure to impose austerity in this Parliament means that the next UK government will have to go harder than it otherwise would to achieve fiscal surpluses, which is the implication of using that sort of terminology, then he clearly is engaging in erroneous deficit scaremongering.

The UK is a currency-issuing government, which means that, ultimately, should it choose, its can divorce its spending choices from the preferences of the currency markets, no matter what the “nostrils” of the latter sense.

It can voluntarily constrain that capacity if it wants and be dictated to by the currency markets. But even though it might pretend that it is ‘funded’ by the bond markets the reality is that the Bank of England has bought massive quantities of gilts (government bonds) through reserve balance expansion.

The Bank of England can buy as much government debt as it wants and could write it off 100 per cent immediately with no real consequence.

So the on-going deficits at present, which are supporting growth, present no particular problem for the next UK Parliament.

Whether larger or smaller deficits or no deficits at all are appropriate after the election will depend on the behaviour of the private domestic sector and the external sector.

At present, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) would suggest that the fiscal deficits are too low given the expenditure drain from the external deficit (currently about 6 per cent of GDP), mostly the result of less-than expected export growth.

The subdued export growth, despite the currency depreciation, is largely the result of the stagnation in the Eurozone. Please read my blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – for more discussion on this point.

Widespread fiscal austerity largely undermines any export-led growth strategy because it reduces national income levels, which, in turn, reduce import expenditure.

The other disturbing trend in the UK is the return to a reliance on rising household debt. Over the last several quarters, the British household saving ratio as a % of disposable income has beeen heading back into the territory that preceded the GFC when Britain was bingeing on private credit and driving housing prices up.

That strategy will prove to be unsustainable.

Housing price inflation, partly driven by the Government poorly thought through housing stimulus bonuses, is partly to blame for the renewed rise in household debt.

So far from the next Parliament inheriting an urgency for lower fiscal deficits, it will have to face the reality of a need for much higher deficits to prevent further financial market chaos (from rising household bankruptcies and mortgages going south) and stagnating economic growth.

And this brings us to the claim that another “sterling crisis” is approaching as the “currency markets” get sick of the “stench” of the “macro manure”.

What exactly is a sterling or currency crisis?

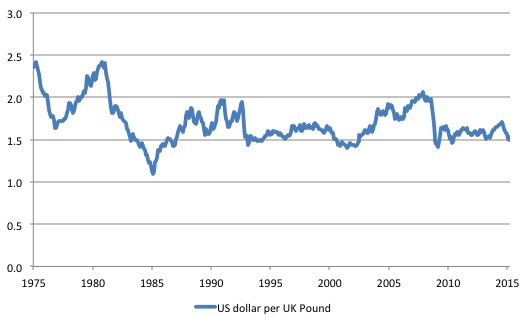

Here is the monthly average UK exchange rate against the US dollar (how many US dollar per Pound) from January 1975 to April 2015. The data comes from the Bank of England.

A rise in the graph indicates an appreciation of the Pound and vice versa.

The big swings in the Pound parity in the 1970s were accompanied by relatively high inflation rates and entrenched economic stagnation.

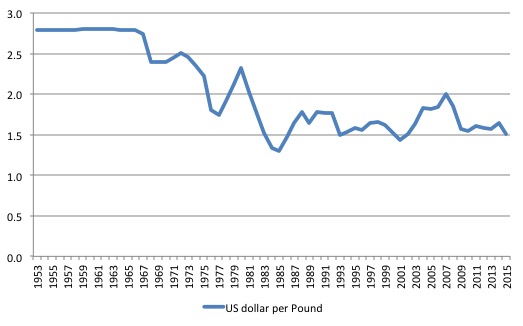

Here is a longer view using average annual data from 1953 to 2015. You gain a view of how much the Pound has depreciated since the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system in August 1971, when President Nixon abandoned the gold window and the US dollar ceased to be convertible into gold.

A currency crisis referred historically to the inability of the central bank to support the agreed parity under the fixed exchange rate system.

As I reiterated yesterday, MMT leads to the understanding that a Current Account deficit (CAD = exports minus imports plus net income flows) can only occur if the foreign sector desires to accumulate financial (or other) assets denominated in the currency of issue of the country with the CAD.

This desire leads the foreign country (whichever it is) to deprive their own citizens of the use of their own resources (real goods and services) and net ship them to the country that has the CAD, which, in turn, enjoys a net benefit (imports greater than exports). A CAD means that real benefits (imports) exceed real costs (exports) for the nation in question.

Thus a CAD signifies the willingness of the citizens to “finance” the local currency saving desires of the foreign sector. MMT thus turns the mainstream logic (foreigners finance a nation’s CAD) on its head in recognition of the true nature of exports and imports.

Subsequently, a CAD will persist (expand and contract) as long as the foreign sector desires to accumulate local currency-denominated assets. When they lose that desire, the CAD gets squeezed down to zero. This might be painful to a nation that has grown accustomed to enjoying the excess of imports over exports. It might also happen relatively quickly. But at least we should understand why it is happening.

Further to this understanding, MMT turns the focus of trade around from the normal mainstream view that CADs are a problem which should be eliminated.

First, it must be remembered that for an economy as a whole, imports represent a real benefit while exports are a real cost. Net imports means that a nation gets to enjoy a higher material living standard by consuming more goods and services than it produces for foreign consumption.

This doesn’t mean that there is not the possibility that severe distributional shifts (in costs and benefits) might occur on a microeconomic level within a nation undergoing a change in patterns of trade. So workers in manufacturing belts might lose their jobs because imported goods become cheaper and consumers (including the same workers who lose work) voluntarily choose to purchase the cheaper (and in some cases, higher quality) products.

While this process is painful appropriate government policy can help to alleviate the costs of adjustment and engender an environment where the workers transit into other uses. Structural adjustment is always painful though and is best achieved at times of full capacity.

Further, even if a growing trade deficit is accompanied by currency depreciation, the real terms of trade are moving in favour of the trade deficit nation (its net imports are growing so that it is exporting relatively fewer goods relative to its imports).

Second, CADs reflect underlying economic trends, which may be desirable (and therefore not necessarily bad) for a country at a particular point in time. For example, in a nation building phase, countries with insufficient capital equipment must typically run large trade deficits to ensure they gain access to best-practice technology which underpins the development of productive capacity.

A current account deficit reflects the fact that a country is building up liabilities to the rest of the world that are reflected in flows in the financial account. While it is commonly believed that these must eventually be paid back, this is obviously false.

As the global economy grows, there is no reason to believe that the rest of the world’s desire to diversify portfolios will not mean continued accumulation of claims on any particular country. As long as a nation continues to develop and offers a sufficiently stable economic and political environment so that the rest of the world expects it to continue to service its debts, its assets will remain in demand.

However, if a country’s spending pattern yields no long-term productive gains, then its ability to service debt might come into question.

Therefore, the key is whether the private sector and external account deficits are associated with productive investments that increase ability to service the associated debt. Roughly speaking, this means that growth of GNP and national income exceeds the interest rate (and other debt service costs) that the country has to pay on its foreign-held liabilities. Here we need to distinguish between private sector debts and government debts.

When Britain participated in the Bretton Woods system it saw the parity of the Pound as a national status symbol reflecting (past) national glories. The fact is that Britain has been losing its place as a world economic power for decades and for years it tried to maintain an overvalued pound at great expense to the population (because it necessitated higher interest rates and higher unemployment that otherwise would have been the case).

This sort of poor decision making occurred as early as the First World War period. At the end of the war, the pound was devalued significantly as a result of the high inflation and costs of servicing the war effort. The Brits tried to regain what they claimed as the rightful value of the pound by pushing up interest rates and imposing fiscal austerity.

The result was that Britain went into stagnation with high unemployment in the 1920s and foolishly Britain went back on the Gold Standard in 1925, which further constrained their options.

The history after that repeats itself as Britain struggled to maintain its parity under the post World War II system of fixed exchange rates. It was forced to devalue in 1949 because the external deficits were supplying massive quantities of sterling into the foreign exchange markets (to pay for the imports) and the Bank of England did not have the foreign reserves necessary to defend the parity (by buying up the excessive sterling volumes).

The on-going external deficits through the 1960s caused further crises in that the nation had to, reluctantly, devalue to maintain its place in the Bretton Woods system.

Britain was locked into a relatively high inflation rate, declining productivity, and had to borrow from the IMF to restore its dwindling foreign reserves. The devaluation in 1967 exacerbated the already persistent inflation rate.

Even after President Nixon withdrew the US from the fixed exchange rate system, the British government continued to maintain the fixed parities in the face of massive foreign exchange market resistance. The pound was under continual pressure to depreciate and the Bank of England was facing on-going shortages of foreign currency reserves.

The grand designs of Britain to maintain their ‘imperial’ position was sheer idiocy.

In 1976 there was a major sterling crisis and the shortage of foreign reserves forced the government to once again call on the IMF for funds. In return, the Government was obliged to impose harsh austerity again which caused unemployment to rise.

The internal instability in Britain with trade unions trying to defend declining real living standards and joblessness rising, led to the end of the Labour era and the rise of Margaret Thatcher.

At least she floated the pound in 1979 and you can see the rapid adjustment (depreciation) that followed as the currency sought some stability point around the trade fundamentals of the nation.

This is the context in which the term “sterling crisis” is historically considered.

What about 2015?

Inflation is zero in Britain.

The Office of National Statistics (ONS) released the latest CPI data yesterday (April 14, 2015) – Consumer Price Inflation, March 2015 Release.

We learn that the rate of inflation over the last year is the:

These are the joint lowest 12-month rates for the Consumer Prices Index on record.

So this situation is not remotely like the state the British economy was in during the classic periods of ‘sterling crisis’.

Further, the Bank of England no longer has to defend any particular parity, which means its foreign reserve holdings are largely irrelevant.

Previously, under the fixed exchange rate system, its capacity to maintain the parity was limited by the pool of foreign currencies it held, which it used to buy the excessive supplies of sterling (relative to the demand for the sterling via export sales).

Now the Bank of England can let the currency go and stabilise at whatever level that arises.

The higher import prices will impact somewhat on the national price inflation but with that rate at zero this is hardly of concern.

Sure enough, the British population will lose real income inasmuch as they buy imports. This will promote substitution away from foreign goods to some extent where local alternatives are available.

So holidays in Ibiza will be replaced by jaunts to Cornwall. Local manufacturers will be boosted. And tourism will be boosted.

The unwillingness of foreigners to hold pounds (which is the manifestation of a currency crisis) will also reduce their desire to send imports to Britain.

But exporters often also have a choice between supplying a local market or an external market. With many nations that trade with Britain still mired in recession and Britain constituting a growing market for their exports, it is far fetched to think that these flows of goods and services will stop quickly as would occur in a full-blown crisis.

It is thus hard to construct anything serious about the possibility that the sterling will depreciate.

People are trying to claim that Britain faces a “Lehman moment” as a currency crisis threatens. Apparently, “we’ll get into a real parabolic phase when you just see the pound drop like a stone” (Source).

This is all bunk. Ridiculous, unfounded scaremongering.

I cannot see the pound spiralling downwards for long if at all. And what if it did go back to its 2009 low of $1.35? I was in the UK in 2009 when the pound was that low and the sky was still above our heads!

Conclusion

I guess the Société Générale dealer brings attention to his company by making these outlandish predictions.

But don’t expect the sky to fall in around the UK as a result of anything that will happen to the exchange rate in the coming months.

There might be an adjustment in the real terms of trade as a result of the on-going rather large external deficits and that will reduce the real standard of living in Britain a bit.

But the overwhelming policy urgency is for the British government to expand its deficit and allow private households space (via income growth) to reduce the dangerous private debt levels. That is the real issue in Britain.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“This might be painful to a nation that has grown accustomed to enjoying the excess of imports over exports. It might also happen relatively quickly. But at least we should understand why it is happening.”

And surely put in place real policies to deal with the situation should it arise – which would be to introduce import rationing so that orders for Leah Jets get shelved and needed goods and services are prioritised.

It’s not capital controls that are required in a crisis. It’s real controls on where the UK’s import demand is directed towards.

That causes an immediate impact on the exporting nation, whose central bank can of course halt any slide in Sterling (which by identity causes an equal and opposite rise in their own currency) instantly and permanently by simply buying up the ‘spare’ Sterling. That would then lift the import controls in the UK.

I see real import controls as a policy mechanism like the Thames Flood Barrier, or the way that share markets are halted if there is a sudden shift in prices. If you put them in place, so that market players know they are there you are unlikely to have to use them. That old expectations thing again.

Dear Bill

You wrote that a country can only run a current-account deficit if foreigners are willing to hold assets denominated in the currency of that country. That’s true of course, but it doesn’t follow that this willingness is the cause of the current-account deficit. Accounting identities are silent on causality.

Suppose that Ruritania exports coffee. Coffee prices are high, and Ruritania has balanced trade. Now there is a sharp drop in coffee prices. As a result, Ruritania starts to run current-account deficits. True, these deficits could not occur without the willingness of foreigners to lend to Ruritanians or buy Ruritanian assets. However, the real cause of the current-account deficit is not the eagerness of foreigners to hold assets in the currency of Ruritania, but the drop in coffee prices.

Regards. James

re. Neil Wilson

This is the view of those who follow Kaldor’s work. Trade balance is an area where a lot of PKs part company with MMT … [Bill EDITED out a sentence] … The Kaldorian view is also much closer to Keynes and the old Cambridge Keynesians.

Again there is really no such thing as the UK nation – we don’t get anything approaching a closed loop production consumption chain in even the most basic or indeed complex of items.

It’s essentially the mirror image of euro and Asian mercantalism.

Therefore a group of Venetians having control of a jurisdictions unit of account does not make a nation.

It’s clearly is not a nation, it’s a base of operations where the crown issues letters of marque to its various corporate raiders in return for a share of the global bounty.

Debates about the value of a stock of debt will not put food on the table for the people without access to a large stock

In real terms the mean British purchasing power has declined because the global system of trade based on usury and the bankers monopoly of credit centered in London is imploding.

The value of British pounds have remained valuable because the authorities have brought in policies to stop the flow in the world system – given the global thermodynamic breakdown we are witnessing this is perhaps the only method the British can use to prevent starvation on that artificially denesly populated island city state and it’s decorative English gardens and villages.

DICTATORSHIP ENGLAND

The Tories have won. Labour has lost forever. The Lib Dems are the gone party.

Yougov predicted polling

277 Labour

264 Tories

28 Lib Dems

326 MPs minimum threshold to form a majority to form a UK parliament.

TORIES OBLIGED TO STAY IN POWER IN A CARETAKER GOVERNMENT

The rules are the sitting UK government has to stay in power in the event of such a severe hung parliament, where no party has reached anything like the number of MPs to form a government.

THIS BRINGS THE THREAT OF REVOLUTION

The national media is doing a complete news blackout in the UK about the parties that are anti austerity and all the social unrest happening by weekly protests, protest marches, sit ins, occupations and national campaigns, with solidarity protests outside head offices elsewhere in the world by trade unions.

The public no longer interest themselves in political parties (it is said) but join by the thousands campaign groups.

But the parties of the poor of the left are growing faster than any so-called big party, with their websites getting far more hits than any party in the media eye.

One example is TUSC – Trade Unionist and Socialist Coaliton – 6th biggest party in all of UK, fielding 135 MP candidates and 1000 councillor candidates – yet entirely ignored by the media.

A FEW VERY OLD WILL VOTE OUT OF HABIT

Labour could still get about 190 Labour MPs from the very old voting the same as in their youth, ignoring and not reading policy, and act as fill-in.

But to form a majority government, the non-voter needs to come out and vote different on Thursday 7 May.

HOW?

113 TUSC candidates in England

59 SNP in all of Scotland

40 Plaid Cymru in all of Wales

6 Mebyon Kernow – the party they hide from the Cornish as their very own party –

single figure marginals of Tories and Lib Dems.

10 Socialist GB MP candidates

Brighton Pavilions has 1 Green MP –

all they will get, as do nothing to save the poor from starvation

Brighton has another 2 voting areas:

Brighton Kemptown – SOCIALIST GB candidate

Brighton and Hove – TUSC candidate

9 THE LEFT UNITY PARTY

eqully for banning welfare sanctions (that will include those in work from next year and become permanent),

benefit cuts, end workfare

NONE OF THESE PARTIES GET ANY MENTION AT ALL IN NATIONAL PRESS

400 MPs plus majority can only be gained by the poor non-voter coming out to vote on Thursday 7 May and voting different.

A multi party group of parties, by UK parliament rules, can form a majority government between them, and can negotiate direclty with each other in government, not only with Labour.

OTHERWISE WE GET REVOLUTION

With a dictatorship Tory government, not voted into power (the same as 2010, Tories not having won outright since 1992), then austerity means the national press will not be able to ignore the explosion of social unrest, when the 75 per cent poor realise their one last hope is gone.

so should we have an international race to consume the fruits of foreign labour?

what is good for the goose is good for the gander.

people in the developed world can afford all those cheap foreign goods

because those workers are being exploited.

what about the unnecessary carbon footprints

the undermining of powerful trade unions

well that horse is bolted collective bargaining is a thing of the past

“And surely put in place real policies to deal with the situation should it arise – which would be to introduce import rationing so that orders for Leah Jets get shelved and needed goods and services are prioritised.”

Agreed. Would export controls ever be necessary? E.g. on food and basic resources, not Leah jets.

Plus you can build up forex reserves if you were exporter in the past. To stop IMF idiocy.

If full employment policies were implemented, would exports increase more than imports?

“Suppose that Ruritania exports coffee. Coffee prices are high, and Ruritania has balanced trade. Now there is a sharp drop in coffee prices. As a result, Ruritania starts to run current-account deficits.”

Decafe or full strength ?

I think the trick is probably to take the policy focus off exports and just let them go where they may. The policy focus should be on maintaining circulation within the currency area and keeping the size of that currency area as large as your power allows you to.

You’re trying to get as many real imports as you can for real exports while trying to get foreigners to hold your scrip – which enlarges your currency area but with entities that are a little more difficult to tax.

I understood the Kaldorians were more interested in the absolute level of balance of payments rather than just managing the rate of change so that it doesn’t change more rapidly that the adaption processes in the currency area can cope with.

Slowing things down isn’t exchange controls. It’s just another buffer process.

“The 1976 events began when the Treasury mandarins advised Prime Minister James Callaghan and Chancellor of the Exchequer Dennis Healey that the Public Sector Borrowing Requirements for 1977-78 and 1978-79 would be exceptionally high, £22bn in total. On this basis the Labour government decided to request a loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and did so on 29 September 1976. . . .

IMF head Witteveen came to London and told Callaghan on 1 December 1976 that his government would have to make cuts to get a loan. After a bit of bluster Callaghan agreed. To implement the IMF deal three weeks of cabinet meetings followed – all conducted in a gravely serious atmosphere – before the cuts were agreed and announced on 21 December 1976.

Three months later the Treasury announced that fresh calculations now showed the PSBR for 1977-1978 would be 50% of the amount they had told Callaghan and Healey six months earlier. The cuts were not needed and nor was the IMF loan.”

http://www.lobster-magazine.co.uk/free/lobster64/lob64-running-britain.pdf

Pension60,

“The rules are the sitting UK government has to stay in power in the event of such a severe hung parliament, where no party has reached anything like the number of MPs to form a government.”

“A multi party group of parties, by UK parliament rules, can form a majority government between them, and can negotiate direclty with each other in government, not only with Labour.”

These seem to me to be in conflict. How would you propose avoidance of this impasse?

Neil Wilson…

“Slowing things down isn’t exchange controls.”

Who mentioned exchange controls? I don’t see any mention of financial controls in anyone’s post. I think everyone is talking about import/export taxes. Are you thinking of Labour policies from Kaldor’s period in government? A lot of his work after that was to figure out what went wrong. I don’t think he ever advocated repeating the same mistakes.

“I understood the Kaldorians were more interested in the absolute level of balance of payments rather than just managing the rate of change so that it doesn’t change more rapidly that the adaption processes in the currency area can cope with.”

As you know the Keynesian view is that mathematical models are weakly predictive shorthand for a much more complicated reality. Kaldor’s view of change was cumulative causation from Gunnar Myrdal. His theoretical framework was non linear. Kaldor introduced the non linear approach in the 1940s. At a conceptual level this is consistent with the recent advances in non linear mathematical models but these mathematical techniques weren’t practical in Kaldor’s time. The rise of complex non linear models has been enabled by computer modelling technology. Before the advent of this technical capacity, non linear mathematical modelling was a highly specialised skill.

Kaldor rejected comparative advantage. The old Keynesians rejected Ricardian trade theory and Ricardo’s critique of mercantilism. This is because Cambridge capital theory is incompatible with comparative advantage. Kaldor’s view of the benefits of export led growth is based on the accumulation of real capital by the exporter. The accumulation of real capital by an exporter gives the exporter the market power to buy raw materials cheap from less developed markets in order to achieve accelerating growth via cumulative causation.

The government does not micro manage secondary spending (or it wouldn’t be secondary spending). Import taxes are an attempt to control second order effects. Markets are never “free markets” and there are always policy options to control trade. Kaldor’s “export led” growth model doesn’t have to be export led. All it implies is that trade balances are a constraint on growth.

Neil

Try essays on economic policy 2 for similar comments to yours. Kaldor’s basic ideas on preventing inflation via taxation were published during the second world war and elaborated in later decades.