Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – January 17, 2015 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Over a given economic cycle (peak to peak), if a nation’s external sector is on average balanced and the government surplus of tax revenue over its spending is, on average, equal to 1 per cent of GDP, then the private domestic sector’s spending-income balance will on average be in:

(a) Deficit of 1 per cent of GDP

(b) Surplus of 1 per cent of GDP

The answer is Deficit of 1 per cent of GDP.

This is a question about sectoral balances. Skip the derivation if you are familiar with the framework.

First, you need to understand the basic relationship between the sectoral flows and the balances that are derived from them. The flows are derived from the National Accounting relationship between aggregate spending and income. So:

(1) Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

where Y is GDP (income), C is consumption spending, I is investment spending, G is government spending, X is exports and M is imports (so X – M = net exports).

Another perspective on the national income accounting is to note that households can use total income (Y) for the following uses:

(2) Y = C + S + T

where S is total saving and T is total taxation (the other variables are as previously defined).

You than then bring the two perspectives together (because they are both just “views” of Y) to write:

(3) C + S + T = Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

You can then drop the C (common on both sides) and you get:

(4) S + T = I + G + (X – M)

Then you can convert this into the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations which allow us to understand the influence of fiscal policy over private sector indebtedness.

So we can re-arrange Equation (4) to get the accounting identity for the three sectoral balances – private domestic, government fiscal balance and external:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

Another way of saying this is that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

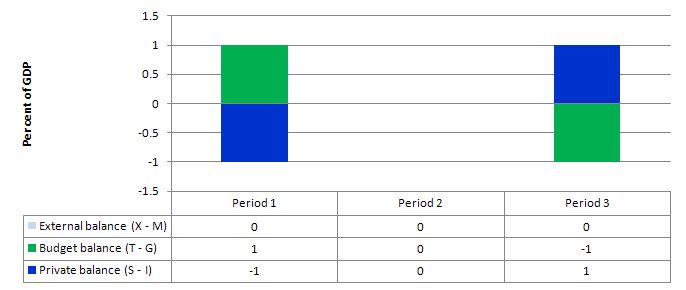

Consider the following graph which shows three situations where the external sector is in balance.

Period 1, is the case in point with the fiscal balance in surplus (T – G = 1) and the private balance is in deficit (S – I = -1). With the external balance equal to 0, the general rule that the government surplus (deficit) equals the non-government deficit (surplus) applies to the government and the private domestic sector. In other words, the private domestic sector must be spending ore than it is earning (a deficit).

In Period 3, the fiscal balance is in deficit (T – G = -1) and this provides some demand stimulus in the absence of any impact from the external sector, which allows the private domestic sector to save (S – I = 1).

Period 2, the fiscal balance is in balance (T – G = 0) and so the private domestic sector must also be in balance (spending equals its earning).

The movements in income associated with the spending and revenue patterns will ensure these balances arise. The problem is that if the private domestic sector desires to save overall then this outcome will be unstable and would lead to changes in the other balances as national income changed in response to the decline in private spending.

So under the conditions specified in the question, the private domestic sector cannot save. The government would be undermining any desire to save by not providing the fiscal stimulus necessary to increase national output and income so that private households/firms could save.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 2:

The immediate expansionary impact of a tax cut, designed to generate $x revenue at the current level of national income, will be less than an increase of public spending cut of $x.

The answer is True.

The question is only seeking an understanding of the initial injection of the spending stream rather than the fully exhausted multiplied contraction of national income that will result. It is clear that the tax rate decrease will have two effects: (a) some initial spending stimulus as people have more disposable income; and (b) it increases the value of the expenditure multiplier, other things equal.

We are only interested in the first effect rather than the total effect. But I will give you some insight also into what the two components of the tax result might imply overall when compared to the impact on demand motivated by an increase in government spending.

To give you a concrete example which will consolidate the understanding of what happens, imagine that the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income is 0.8 and there is only one tax rate set at 0.20. So for every extra dollar that the economy produces the government taxes 20 cents leaving 80 cents in disposable income. In turn, households then consume 0.8 of this 80 cents which means an injection of 64 cents goes into aggregate demand which them multiplies as the initial spending creates income which, in turn, generates more spending and so on.

Government spending increase

A rise in government spending (say of $1000) is what we call an exogenous injection to the aggregate spending stream and this directly increases aggregate spending (demand) by that amount. So it might manifest as a new order for $1000 worth of gadget X from some private supplier.

The firm that produces gadget X thus will increase the production of the good or service by the amount of the new orders ($1000) and as a result incomes of the productive factors working for and/or used by the firm also increase by $1000. So the initial rise in aggregate demand is $1000. Remember that spending equals income.

This initial rise in national output and income would then induce a further rise in consumption by 64 cents in the dollar so in Period 2, aggregate demand would rise by a further $640. Output and income then rise further by the same amount to meet this increase in spending and sales (spread throughout the economy).

In Period 3, aggregate demand rises by 0.8 x 0.8 x $640 and so on. The induced spending increase gets smaller and smaller because some of each round of income rise is taxed away, some goes to a rise in imports and some manifests as a rise in saving.

Tax-decrease induced expansion

The expansion coming from a tax-cut does not directly impact on the spending stream in the same way as the rise in government spending.

First, the question assumes that the government introduces a tax rate cut that increases its initial fiscal deficit by the same amount as would have been the case if it had increased government spending (so in our example, $1000).

In other words, overall disposable income at each level of GDP rises initially by $1000. What happens next?

Some of the rise in disposable income manifests as increased saving (20 cents in each dollar). So the stimulus to consumption spending is equal to the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income (0.8) times the rise in disposable income (which if the MPC is less than 1 will be lower than the $1000).

In this case the rise in aggregate demand is $800 rather than $1000 in the case of the increase in government spending.

What happens next depends on the parameters of the macroeconomic system. The multiplied rise in national income may be higher or lower depending on these parameters. But it will never be the case that an initial fiscal equivalent tax cut will provide more stimulus to national income than a rise in government spending.

Note in answering this question I am disregarding all the nonsensical notions of Ricardian equivalence that abound among the mainstream economists. I am also ignoring the empirically-questionable mainstream claims that tax decreases stimulate work incentives which force each worker to supply more labour. You can avoid this issue by imagining that the tax cut is in the form of a change to a value-added tax.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

Question 3:

If the external sector is accumulating financial claims on the local economy (that is, providing foreign savings to the domestic economy) and the GDP growth rate is lower than the real interest rate, then the private domestic sector and the government sector can run surpluses without damaging employment growth.

The answer is False.

When the external sector is accumulating financial claims on the local economy it must mean the current account is in deficit – so the external balance is in deficit. Under these conditions it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the national accounting rules and income adjustments will always ensure that is the case.

The relationship between the rate of GDP growth and the real interest rate doesn’t alter this result and was included as superflous information to test the clarity of your understanding.

To understand this we need to begin with the national accounts which underpin the basic income-expenditure model that is at the heart of introductory macroeconomics. See the answer to Question 1 for the background conceptual development.

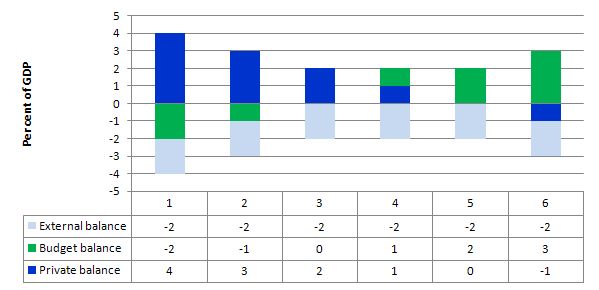

Consider the following graph and associated table of data which shows six states. All states have a constant external deficit equal to 2 per cent of GDP (light-blue columns).

State 1 show a government running a surplus equal to 2 per cent of GDP (green columns). As a consequence, the private domestic balance is in deficit of 4 per cent of GDP (royal-blue columns). This cannot be a sustainable growth strategy because eventually the private sector will collapse under the weight of its indebtedness and start to save. At that point the fiscal drag from the fiscal surpluses will reinforce the spending decline and the economy would go into recession.

State 2 shows that when the fiscal surplus moderates to 1 per cent of GDP the private domestic deficit is reduced.

State 3 is a fiscal balance and then the private domestic deficit is exactly equal to the external deficit. So the private sector spending more than they earn exactly funds the desire of the external sector to accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue in this country.

States 4 to 6 shows what happens when the fiscal balance goes into deficit – the private domestic sector (given the external deficit) can then start reducing its deficit and by State 5 it is in balance. Then by State 6 the private domestic sector is able to net save overall (that is, spend less than its income).

Note also that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts.

Most countries currently run external deficits. The crisis was marked by households reducing consumption spending growth to try to manage their debt exposure and private investment retreating. The consequence was a major spending gap which pushed fiscal balances into deficits via the automatic stabilisers.

The only way to get income growth going in this context and to allow the private sector surpluses to build was to increase the deficits beyond the impact of the automatic stabilisers. The reality is that this policy change hasn’t delivered large enough fiscal deficits (even with external deficits narrowing). The result has been large negative income adjustments which brought the sectoral balances into equality at significantly lower levels of economic activity.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

It’s all pretty clear, but can you please clarify one thing: when it comes to usage of national income you mention only of households, but national income is earned in form of profits too. Doesn’t the way the accounting is stated imply the counterfactual assumption that all profits have been distributed to households? Or can you ignor this inaccuracy because the impact is trivial? Or do I miss something?