I am late today because I am writing this in London after travelling the last…

Australia labour force data – now a million underemployed

Today’s release of the – Labour Force data – for August 2014 by the Australian Bureau of Statistics revealed an extraordinary rise in part-time employment and a decline in unemployment. The results are suspicious as the ABS themselves acknowledge. Despite the massive increase in part-time employment, total working hours barely rose and the upshot was the underemployment jumped sharply. There are now more than 1 million workers in Australia who are underemployment. The broad labour underutilisation rate jumped from 13.5 to 14.6 per cent. Teenagers gained some of the part-time employment growth but full-time employment slumped further. The Government will be claiming the employment reversal is a vindication of their economic policy – but we will have to see if the sudden jump is sustained or is a statistical artifact.

The summary ABS Labour Force (seasonally adjusted) estimates for August 2014 are:

- Employment increased 121,000 (1.04 per cent) with full-time employment increasing by 14,300 and part-time employment rising by a staggering 106,700.

- Unemployment increased by 33,500 to 755,100.

- The official unemployment rate fell by 0.3 points to 6.1 per cent.

- The participation rate rose by 0.4 percentage points to 65.2 per cent. It is still well below its November 2010 peak (recent) of 65.9 per cent.

- Aggregate monthly hours worked increased by 0.1 million hours (0.01 per cent).

- The quarterly ABS broad labour underutilisation estimates (the sum of unemployment and underemployment) were published in the August release and underemployment rose by 0.9 percentage points to 8.5 per cent and total labour underutilisation rate rose sharply to 14.5 per cent. There are now 1,053.2 thousand persons underemployed. Overall, there are 1.8083 million workers either unemployed or underemployed.

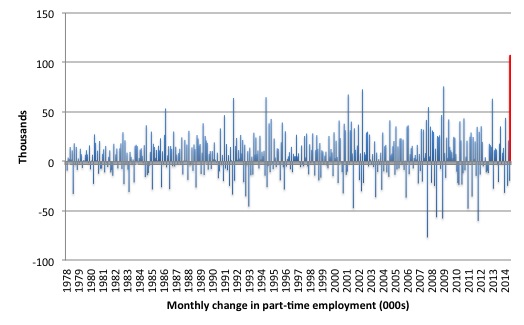

The very strong increase in employment is difficult to believe. To see how much of an outlier it is I produced this graph, which shows the monthly change in part-time employment since February 1978.

The ABS say:

Because of the unusually strong increase in employment estimates, the ABS has extensively checked the data.

The huge increase in part-time employment is explained by the ABS after an investigation in this way:

1. The Labour Force survey instrument was changed in July 2014 – the ABS eliminate this as a cause.

2. The way the rotation groups are questioned (additional surveys are conducted) was eliminated as a possible cause.

3. A new processing system is being introduced for the Labour Force Survey was eliminated as a possible cause.

4. The seasonal adjustment system was stable.

5. The raw survey records were checked and seemed ok.

6. The “methodologies used to compile the August 2014 estimates and identified no deficiencies in these methodologies”.

In other words, the ABS consider the result to be genuine. If it is then it is one of the most startling monthly reversals of all time. We will see what happens next month.

Some background to general movements in the labour market at present. This morning it was revealed that a large food company operating in Australia was launching an attack on the wages of its workers. The Melbourne Age report – Coca-Cola Amatil slashes wages with new employees to work for less.

The Report said that all workers were having their wages frozen and any “new hires will receive pay of 38 per cent less to do the same job under new pay deals that provide a stark warning of the pressure on wages across the economy.”

Under the protection of the conservative government in Canberra, the capitalists are effectively declaring war on their workforces to make more profits.

Consumers are encouraged to declare war on the companies in return.

The company and the sycophants in the media claimed that the wage cuts would lead to higher employment. But the Report quoted a major bank economist as refuting that claim:

You’d hope employers would hire more people and invest in their businesses, but the reality is employers are not, because when demand picks up they just run their businesses a bit harder … Business shouldn’t dismiss the impact of weak customer sentiment and low consumption numbers, because ultimately that’ll hit their bottom line.

Exactly, wages are both a cost and income. The income leads to purchases. Cutting costs through attacks on workers’ conditions does nothing for productivity and constrains total spending.

This is the environment that we are now facing though. Myopic employers who are being geejed up by the anti-worker hectoring of various federal government ministers to wade in and cut wages and other conditions.

Employment growth – strong but not necessarily believable

The data for August reveals a stark upward shift in employment growth – the vask bulk of it being manifested in the extraordinary rise in part-time employment.

Total employment increased 121,000 (1.04 per cent) with full-time employment increasing by 14,300 and part-time employment rising by a staggering 106,700. As noted earlier, this is a very ‘rogue’ result and until we get further information we have to be suspicious.

Over the last 24 months or so we have seen the labour market data switching back and forth regularly between negative employment growth and positive growth spikes. This month’s figure, however, is the strongest overall performance in that time.

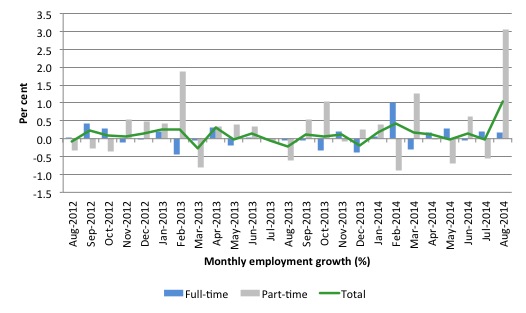

The following graph shows the month by month growth in full-time (blue columns), part-time (grey columns) and total employment (green line) for the 24 months to August 2014 using seasonally adjusted data. It gives you a good impression of just how flat employment growth has been until that huge spike in part-time employment in the August survey.

As a long-time analyst of time series data, this sort of result is rare and usually associated with a major event. There is nothing that I can think of that would lead to such a spike upwards. Stay tuned.

While full-time and part-time employment growth are fluctuating around the zero line, total employment growth is still well below the growth that was boosted by the fiscal-stimulus in the middle of 2010.

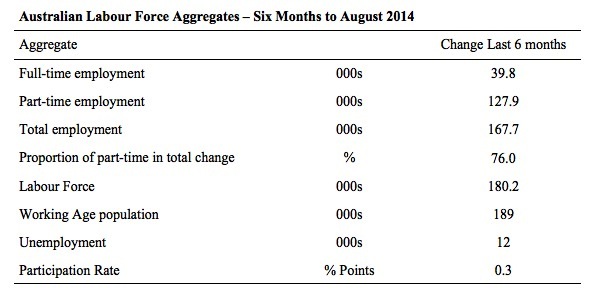

The following table provides an accounting summary of the labour market performance over the last six months. The monthly data is highly variable so this Table provides a longer view which allows for a better assessment of the trends. WAP is working age population (above 15 year olds).

The conclusion – overall there have 167.7 thousand jobs (net) added in Australia over the last six months. Full-time employment has risen by 39.8 thousand jobs (net) while part-time work has risen by 127.9 thousand jobs. All of that rise in part-time employment has come in the last month.

The Working Age Population has risen by 189 thousand in the same period while the labour force has risen by 180.2 thousand. The participation rate has risen by 0.3 percentage points over the last six months.

Notwithstanding this month’s exceptional employment growth, overall it has not been able to keep pace with the underlying population growth and unemployment has risen by 12 thousand as a result.

Today’s data release is a stark change to the trends of the last 24 months or so and we will have to treat it with some skepticism.

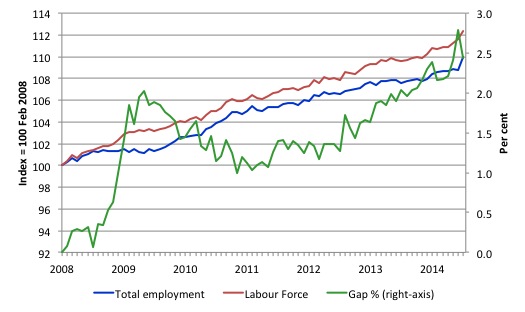

To put the recent data in perspective, the following graph shows the movement in the labour force and total employment since the low-point unemployment rate month in the last cycle (February 2008) to August 2014. The two series are indexed to 100 at that month. The green line (right-axis) is the gap (plotted against the right-axis) between the two aggregates and measures the change in the unemployment rate since the low-point of the last cycle (when it stood at 4 per cent).

You can see that the labour force index has largely levelled off yet the divergence between it and employment growth has risen sharply (in spurts) over the last several months.

The Gap series gives you a good impression of the asymmetry in unemployment rate responses even when the economy experiences a mild downturn (such as the case in Australia). The unemployment rate jumps quickly but declines slowly.

It also highlights the fact that the recovery has not strong enough to bring the unemployment rate back down to its pre-crisis low. You can see clearly that the unemployment rate fell in late 2009 and then has hovered at the same level for some months before rising again over the last several months.

Since the current government was elected in September 2013, the situation has deteriorated significantly.

The Gap shows that the labour market is now in worse shape than it was at the peak of the financial crisis in 2009. After the government prematurely terminated the fiscal stimulus the situation has progressively deteriorated.

In August 2014, the Gap of 2.4 percentage points and remains above the levels that appeared in May and June 2009 when the Australian economy was enduring the impact of the crisis. All the gains made since then have thus largely disappeared due to poorly crafted fiscal policy not responding appropriately to non-government spending changes.

Today’s results to not (as yet) signify a change in the upward bias in the unemployment rate.

Full-time and Part-time employment in recovery

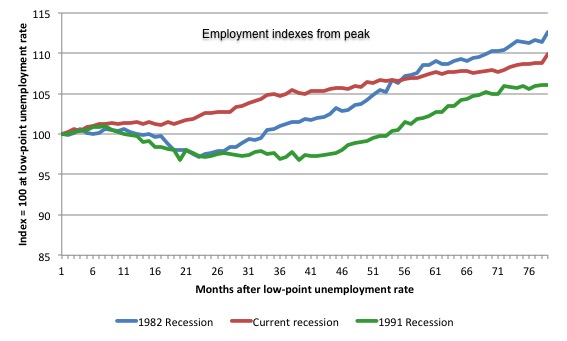

The following graph shows employment indexes for the last 3 recessions and allows us to see how the trajectory of total employment after each peak prior to the three major recessions in recent history: 1982, 1991 and 2009 (the latter to capture the current episode).

The peak is defined as the month of the low-point unemployment rate in the relevant cycle and total employment was indexed at 100 in each case and then indexed to that base for each of the months as the recession unfolded.

I have plotted the 3 episodes for 78 months after the low-point unemployment rate was reached in each cycle. The current episode is now in its 78th month.

The initial employment decline was similar for the 1982 and 1991 recessions but the 1991 recovery was delayed by many month and the return to growth much slower than the 1982 recession.

The current episode is distinguished by the lack of a major slump in total employment, which reflects the success of the large fiscal stimulus in 2008 and 2009.

However, the recovery spawned by the stimulus clearly dissipated once the fiscal position was reversed and the economy is now producing very subdued employment outcomes.

Moreover, the current episode is also different to the last two major recessions in the sense that the recovery is over and the economy is deteriorating again.

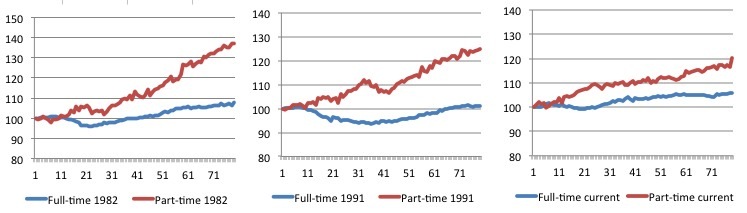

The next 3-panel graph decomposes the previous graph into full-time and part-time employment. The vertical scales are common to allow a comparison between the three episodes.

First, after the peak is reached, part-time employment continues to increase as firms convert full-time jobs into fractional jobs.

Second, recoveries are dominated by growth in part-time employment as firms are reluctant to commit to more permanent arrangements with workers while there is uncertainty of the future course in aggregate demand.

Third, the current recovery is clearly mediocre by comparison, with both very subdued growth in full-time and part-time work.

Teenage labour market – some growth

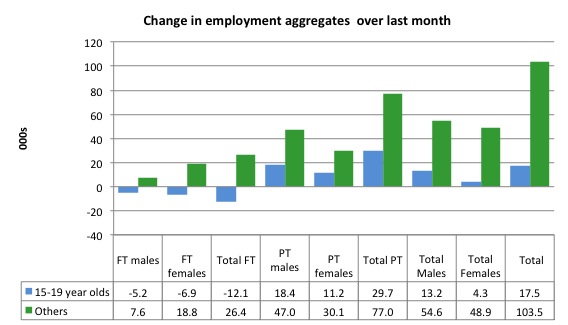

While the staggering rise in part-time jobs this month helped teenagers gain 29.7 thousand new jobs, those gains were offset by a major decline of 12.1 thousand full-time jobs (net), leaving the overall gain of 17.5 thousand net.

At least that is growth. If the part-time growth is to be believed it also scuttles the claims by the employer groups that the current penalty rate regime for weekend work etc prevents part-time employment being created!

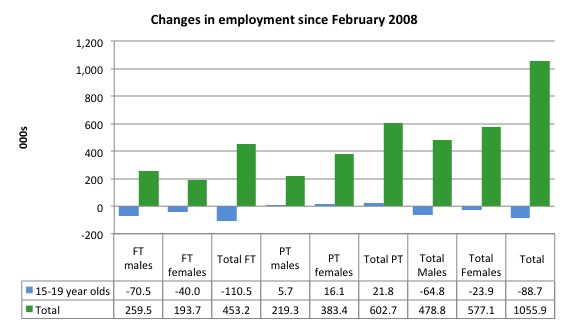

The following graph shows the distribution of net employment creation in the last month by full-time/part-time status and age/gender category (15-19 year olds and the rest)

If you take a longer view you see how poor the situation remains.

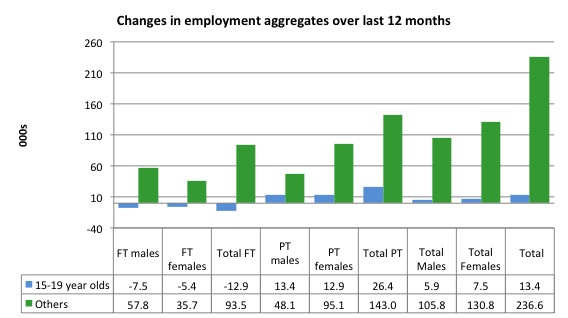

Over the last 12 months, teenagers have gained only 13.4 thousand jobs while the rest of the labour force have gained 236.6 thousand net jobs. Remember that the overall result represents a fairly poor annual growth in employment (and has been skewed by the August month’s result).

The teenage segment of the labour market is being particularly dragged down by the sluggish employment growth, which is hardly surprising given that the least experienced and/or most disadvantaged (those with disabilities etc) are rationed to the back of the queue by the employers.

The following graph shows the change in aggregates over the last 12 months.

To further emphasise the plight of our teenagers, I compiled the following graph that extends the time period from the February 2008, which was the month when the unemployment rate was at its low point in the last cycle, to the present month (August 2014). So it includes the period of downturn and then the so-called “recovery” period. Note the change in vertical scale compared to the previous two graphs.

Since February 2008, there have been only 1,055.9 thousand (net) jobs added to the Australian economy but teenagers have lost a staggering 88.7 thousand over the same period. It is even more stark when you consider that 110.5 thousand full-time teenager jobs have been lost in net terms.

Even in the traditionally, concentrated teenage segment – part-time employment, teenagers have only been able to gain a miserable 21.8 thousand jobs (net) even though 602.7 thousand part-time jobs have been added overall.

Overall, the total employment increase is modest. Further, around 58 per cent of the total (net) jobs added since February 2008 have been part-time, which raises questions about the quality of work that is being generated overall.

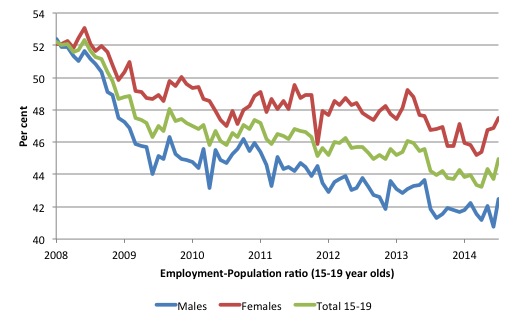

To put the teenage employment situation in a scale context the following graph shows the Employment-Population ratios for males, females and total 15-19 year olds since March 2008 (the month which coincided with the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle).

You can interpret this graph as depicting the loss of employment relative to the underlying population of each cohort. We would expect (at least) that this ratio should be constant if not rising somewhat (depending on school participation rates).

The facts are that the absolute loss of jobs reported above is depicting a disastrous situation for our teenagers. Males, in particular, have lost out severely as a result of the economy being deliberately stifled by austerity policy positions.

The male ratio has fallen by 11.6 percentage points since February 2008, the female by 5.3 percentage points and the overall teenage employment-population ratio has fallen by 8.5 percentage points.

The overall ratio fell again this month by some 0.6 percentage points.

Overall, the performance of the teenage labour market continues to be deeply disturbing. It doesn’t rate much priority in the policy debate, which is surprising given that this is our future workforce in an ageing population. Future productivity growth will determine whether the ageing population enjoys a higher standard of living than now or goes backwards.

The best the Government appears to be capable of is to dream up plans which deny income support to this group and impose impossible activity tests on them.

The longer-run consequences of this teenage “lock out” will be very damaging.

The problem is that in the modest growth period that the Australian labour market enjoyed as a result of the fiscal stimulus and mining investment, teenagers failed to participate in the gains – they went backwards.

It remains that the teenage cohort is not benefiting from the modest growth at present.

I continue to recommend that the Australian government immediately announce a major public sector job creation program aimed at employing all the unemployed 15-19 year olds, who are not in full-time education or a credible apprenticeship program.

The Government should abandon their ideological obsession with supply-side punishment regimes and realise that the unemployed cannot search for jobs that are not there.

It is clear that the Australian labour market continues to fail our 15-19 year olds. At a time when we keep emphasising the future challenges facing the nation in terms of an ageing population and rising dependency ratios the economy still fails to provide enough work (and on-the-job experience) for our teenagers who are our future workforce.

Unemployment – sharp fall

The unemployment rate fell by 0.3 percentage points to 6.1 per cent in August 2014. Official unemployment fell by 33,500 to 755,100. The rise was a combination of the strong employment growth being offset by the 0.3 percentage point jump in participation.

Overall, the labour market still has significant excess capacity available in most areas and what growth there is is not making any major inroads into the idle pools of labour.

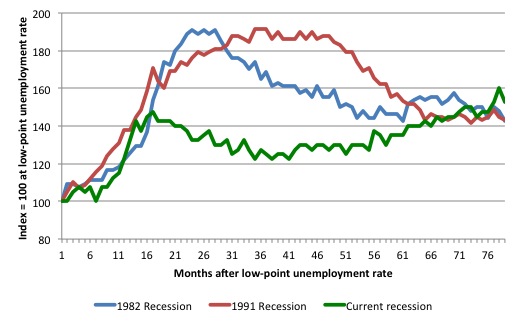

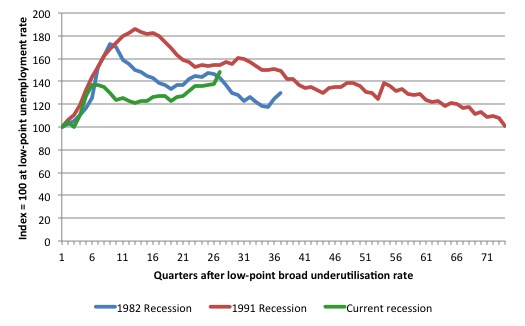

The following graph updates my 3-recessions graph which depicts how quickly the unemployment rose in Australia during each of the three major recessions in recent history: 1982, 1991 and 2009 (the latter to capture the 2008-2010 episode). The unemployment rate was indexed at 100 at its lowest rate before the recession in each case (January 1981; January 1989; May 2008, respectively) and then indexed to that base for each of the months as the recession unfolded.

I have plotted the 3 episodes for 79 months after the low-point unemployment rate was reached in each cycle. The current episode is now in its 79th month (0 being February 2008). For 1991, the peak unemployment which was achieved some 38 months after the downturn began and the resulting recovery was painfully slow. While the 1982 recession was severe the economy and the labour market was recovering by the 26th month. The pace of recovery for the 1982 once it began was faster than the recovery in the current period.

It is significant that the current situation while significantly less severe than the previous recessions is dragging on which is a reflection of the lack of private spending growth and declining public spending growth.

Moreover, the current episode is also different to the last two major recessions in the sense that the recovery is over and the economy is deteriorating again.

In relative terms, the current episode is now worse than the other two recessions (in terms of deviation from low-point unemployment rate).

The graph provides a graphical depiction of the speed at which the recession unfolded (which tells you something about each episode) and the length of time that the labour market deteriorated (expressed in terms of the unemployment rate).

From the start of the downturn to the 79-month point (to August 2014), the official unemployment rate has risen from a base index value of 100 to a value 152.5. After falling steadily as the fiscal stimulus pushed growth along (it reached 122.5 after 35 months – in January 2010), it has been slowly trending up for some months now. Unlike the other episodes, the current trend, at this stage of the cycle, is upwards and accelerating.

It is now above the peak that was reached just before the introduction of the fiscal stimulus. In other words, the gains that emerged in the recovery as a result of the fiscal stimulus in 2009-10 have now been lost.

At 78 months, 1982 index stood at 142.6 (and falling) while the 1991 index was at 143.1 (and falling). It is clear that at an equivalent point in the “recovery cycle” the current period is more sluggish than our recent two major downturns and trending upwards while the trend in the earlier episodes was moderately downwards.

It now appears that the recoveries have converging, which tells us that the current policy has failed to take advantage of the fact that the latest economic downturn was much more mild than the previous recessions. In other words, the policy failure is locking the economy into a higher unemployment rate than is desirable and otherwise attainable.

Note that these are index numbers and only tell us about the speed of decay rather than levels of unemployment. Clearly the 6 per cent at this stage of the downturn is lower that the unemployment rate was in the previous recessions at a comparable point in the cycle although we have to consider the broader measures of labour underutilisation (which include underemployment) before we draw any clear conclusions.

The notable aspect of the current situation is that the recovery is very slow.

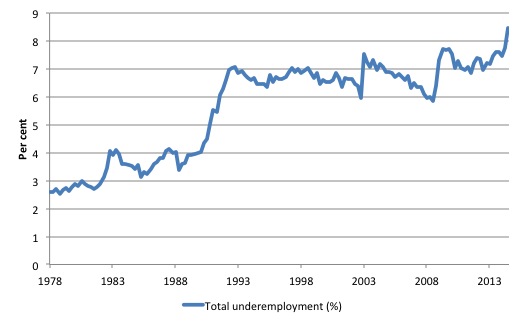

Broad labour underutilisation – rises sharply

The ABS published its quarterly broad labour underutilisation measures in the August data release. The extraordinary rise in part-time employment was accompanied by a sharp rise in underemployment. So the decline in unemployment has to be seen in that light.

In the August-quarter, total underemployment rose from 7.6 per cent to 8.5 per cent and the ABS broad labour underutilisation rate rose to 14.6 per cent (the sum of unemployment and underemployment).

| There are now 1,053.2 thousand persons underemployed. Overall, there are 1.8083 million workers either unemployed or underemployed. |

The following graph plots the history of underemployment in Australia since February 1978.

If hidden unemployment is added to the broad ABS figure the best-case (conservative) scenario would see a underutilisation rate well above 17 per cent at present. Please read my blog – Australian labour underutilisation rate is at least 13.4 per cent – for more discussion on this point.

The following graph shows the same type of indexes as the previous graph except it uses the ABS broad labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment). It also is in terms of quarters rather than months.

We also show the full evolution of the the 1982 and 1991 episodes from the low-point (= 100) through the peak and back to the next low-point. In the case of the 1982 recession the index had risen to a peak of 172.8 in May 1983 (a broad underutilisation rate of 14.4 per cent) and then fell back to 9.8 per cent by November 1989 (index value 117.4).

At that point, the cycle turned down again signalling the beginning of the 1991 recession. That cycle reached a peak of 185 (or 18.1 per cent in November 1992) and it took until February 2008 for it to reach the low-point of 9.9 percent (an index value of 100.9). That point marked the beginning of the next cycle.

That should tell you how severe the 1991 recession was and how asymmetric the labour market response is on either side of the cycle. From its start in November 1989 it took 74 quarters (18.5 years) to return to more or less that level.

In terms of the three recession comparison, at the same period in the recovery (using quarterly data), the broad labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) had an index value of 143 in the 1982 recession (absolute value of 11.9 per cent); an index value of 154.5 in the 1991 recession (absolute value of 15.1 per cent); and an index value of 148.1 in the current period (absolute value of 14.6 per cent).

So while the level of unemployment is much lower now than in the 1982 recession (at a comparable stage), underemployment is now much higher and so the total labour underutilisation rates is higher. Further, the 1982 recovery in broad underutilisation terms was more robust than the current stagnating situation.

Commentators who think of the 1982 recession as severe, rarely see it in these terms. Joblessness is probably worse than underemployment but both mean that labour is wasted and income earning opportunities are being foregone. For a worker with extensive nominal commitments, the loss of income when hours are rationed may be no less severe than the loss of hours involved in unemployment, if the threshold of solvency is breached.

The next update will be in the August Labour Force data release.

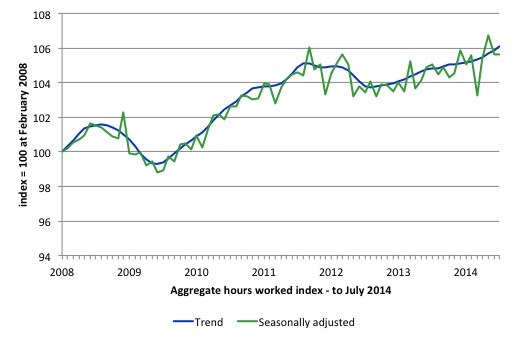

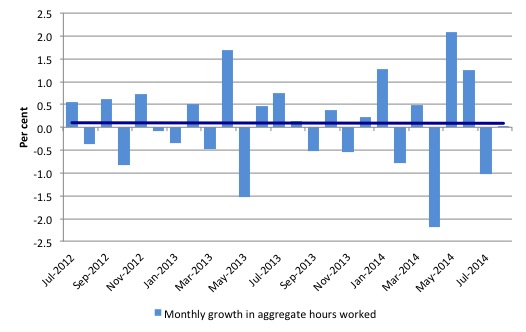

Hours worked – fell in August 2014

Aggregate monthly hours worked increased 0.1 million hours (0.01%) in August 2014 in seasonally adjusted terms.

That is, basically not at all. All the part-time employment growth added nothing to overall working hours but a lot to underemployment.

The following graph shows the trend and seasonally adjusted aggregate hours worked indexed to 100 at the peak in February 2008 (which was the low-point unemployment rate in the previous cycle).

The next graph shows the monthly growth (in per cent) over the last 24 months. The dark linear line is a simple regression trend of the monthly change – which depicts a zero trend. You can see the pattern of the change in working hours is also portrayed in the employment graph – zig-zagging across the zero growth line.

Conclusion

In general, we always have to be careful interpreting month to month movements given the way the Labour Force Survey is constructed and implemented.

Today’s data release is a classic example of monthly variability. I am deeply suspicious of the sudden spike in part-time work as the ABS was themselves.

The sudden rise in part-time employment certainly reduced the unemployment rate but at the same time the underemployment rate rose quickly and underemployment topped the million mark for the first time.

The teenage labour market, which is in a parlous state, deteriorated further in August 2014 because full-time employment fell sharply. This is an emergency being ignored by the Federal Government.

The neglect of our teenagers will have a very long memory indeed and the negative consequences will be stronger given the ageing population.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

While we may need growth of some sort to reduce unemployment we certainly don’t need growth in population.

For a comprehensive breakdown of the affects of immigration on unemployment go to the Centre for Population and Urban Research (CPUR) website which is part of the Monash University site.

This is a research report published in August 2014 by Bob Birrell and Ernest Healy.

As the overwhelming majority of recent immigrants HAVE to be skilled and HAVE to be sponsored by an employer to continue to live here, that’s no surprise. Contrary to popular belief it is not easy to get into Australia without either a degree or a job in place.

Matthew B,

One of the cleaners at my workplace is leaving and we are looking for a replacement. One of the applicants is a woman of Thai origin. Her qualifications include a Batchelor of Science from King Mongok’s University. Scrolling down the list of references, they are a long list of cleaning and food preparation jobs in supermarkets and McDonalds restaurants in the US.

Exactly why is someone with a science degree looking for a cleaners job and why do they not appear to have ever held a position relevent to their supposed qualifications?

I have no qualms whatsoever with people trying to improve their circumstances but I’m going to call BS on this one, there’s a rort of some sort here. Meanwhile, our own youth unemployment rate is appalling.

I have an honours degree in economics and pulled out of my Phd two years into it due to a serious illness which I managed to overcome.

My goals before I became ill were much different to what they are now. Back then all I did was study / research and teach / lecture / tutor. My only goal is to stay healthy – anything beyond that is a bonus.

I now work in a low skilled / low paid job and have no plans of ever using my degree to move into something that pays more.

Hence, I can totally understand a person having a degree and yet never using it.

Alternatively, I can also understand people with degrees refusing to tak on work they feel is beneath them as well.

Matthew B,have you read the CPUR report ?

[BILL NOTES: I EDITED OUT SOME DISDAINFUL PERSONAL ABUSE HERE – PLEASE KEEP TO THE ISSUES NOT THE PERSON]

Alan Dunn,your situation is regrettable and I hope your health improves.

However, this has zero to do with the example mentioned by Lefty.

The woman he mentioned is prepared to use any means to gain entry to Australia and any means to stay under any pretext. There are many,many thousands of the same ilk.The student pretext is one of the main methods.

Australia is the most expensive country for foreign students. Why do they continue to flock here when they can study elsewhere for much less outlay ?

What we have here is a politically bipartisan determination to maintain high immigration levels in blatant disregard for ordinary sense and the welfare of Australian citizens.They are supported in this by the oligarchy and the pitiful Do Gooders and Bleeding Hearts Coalition.

Go figure where this is going to end up.

@Podargus you can’t blame people for wanting the same thing you or I have as a pure accident of birth..

And who will support the growth of middle class slum lords, not to mention the higher end of the construction market?

I read in the sydney paper homeless people have set up a shanty town under a bridge at wentworth park, and the locals are outraged. meanwhile the state sells off housing at millars point, under the pretext of capital raising to build more houses in some far flung part of the city.

Our leaders are nasty and gave up a long time ago at being anything but self interested. So don’t look to them 🙂