I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The intergenerational consequences of austerity will be massive

There was an interesting article in the Washington Post over the weekend (September 7, 2013) – Why Keynes wouldn’t have too rosy a view of our economic future – written by – Mike Konczal. It broaches the topic of self-adjustment in capitalist monetary economies and the divide within the economics profession with respect to that topic. It also introduces the issue that the long-run trajectory of the economy is dependent on the short-run path taken (the so-called hysteresis hypothesis), which is largely ignored by those who advocated fiscal austerity. What is typically denied is that the costs of fiscal austerity are more than a temporary increase in unemployment and lost income. The intergenerational consequences and the impact on the capacity of the economy are likely to be massive.

The Washington Post article carried the following graphic. The article is about how we think of the output gap. Whether it is a temporary phenomenon, which will disappear soon as private economic activity recovers or perhaps it becomes a permanent feature – “what if the gap never closes?”

Mike Konczal notes that the output gap has “been remarkably constant through the ‘recovery'” and how we discriminate between these two polar opposites “matters for government policy” but:

… it also matters because this question has historically been one of the most contentious in economic theory. It is what separates John Maynard Keynes from his predecessors, and it is what separates “Old Keynesians” from “New Keynesians.”

This paradigmic angle was taken up by – Auto-Corect Nt Wokring (Wonkish) – Paul Krugman (September 8, 2013), who continues to argue that the “standard” textbook macroeconomic model is adequate for understanding why the major economies are bogged down with huge output gaps.

Paul Krugman also says that eventually all economies recover (once there is sufficient scarcity of capital) and so “depressions aren’t forever”. I agree with that although that is not the most interesting aspect of the Washington Post article nor is the analysis Paul Krugman uses to make his point vaguely useful (IS-LM, AS-AD framework that is basically not of any use at all).

The New Keynesian framework, which Paul Krugman continually defends (because he operates within it) is deeply flawed and will have to be abandoned if we are to make progress in the understanding of macroeconomics.

Please read my blog – Mainstream macroeconomic fads – just a waste of time – for more discussion on this point.

But lets go back to the Mike Konczal article, which is more interesting.

He juxtaposes New Keynesians who he says consider the business cycle to arise from some “failure” – a “friction” or market “imperfection” which prevents agents from “spending” according to their optimal lifetime path. As a result, recessions (the “Keynesian” part of New Keynesian economics) result from wage and price rigidity or some other rigidity that prevents the free market outcomes from manifesting.

Eventually, for example, consumers will catch up and based on their lifetime spending plans will make up for the lack of spending now:

… since this problem causes less spending now, it must cause more spending later. So efforts to pull that future spending toward the present can make everyone better off.

As a result the economy is “certain” to “recover to its potential, given enough time”. The more extreme New Keynesians advocate no government intervention, while the less extreme proponents (such as Paul Krugman) recognise that some intervention will “pull” the future spending plans forward and hasten the private spending recovery.

Mike Konczal argues that Keynes did not think this would occur and “Old Keynesians” (quoting Keynes) thought:

… rejected the idea that the existing economic system is, in any significant sense, self-adjusting.

In other words, an economy can become stuck at some macroeconomic equilibrium, where firms are happy to supply goods and services and a level which satisfies the spending plans of consumers, but where substantial unemployment persists and, presumably, the economy is operating well below potential.

At that point, there is no incentive for firms to increase output and national income and no incentive for consumers to alter their spending and saving patterns.

Mike Konczal notes that the “labor force would then do the adjusting, with people simply giving up looking for work”. that is, the unemployment rate may start to fall and the asymptote as a result of the participation rate declining and the labour force shrinking.

Mike Konczal considers the New Keynesian idea that we all have worked out optimal, life-time plans about our spending and that we eventually get back onto those life-time trajectories, interrupted by undershoots and overshoots, to be far-fetched and not in the spirit of what Keynes thought.

He says that an economy can “get stuck” because:

… aggregate spending mainly depends on current income …

That is, when national income starts to fall and unemployment rises, households adopt conservative positions with respect to the spending plans. These positions are difficult to alter unless there is some external shock (for example, a government stimulus).

I have written about the US output gap in the past. For example, please read my blog – US problems are cyclical not structural – for more discussion on this point.

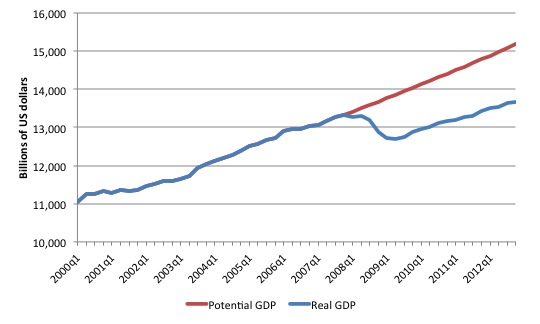

The following graph shows the actual real GDP for the US (in $US billions) as at April 2013 and an estimate of the potential GDP. In the blog cited above, I explain how I estimated the potential output, given it is unobservable.

In this case, simple trend extrapolation was used from the most recent real GDP peak (December-quarter 2007). The projected rate of growth was the average quarterly growth rate between 2001Q4 and 2007Q4, which was a period (as you can see in the graph) where real GDP grew steadily (at 0.62 per cent per quarter) with no major shocks. If the global financial crisis had not have occurred it would be reasonable to assume that the economy would have grown along the red line (or thereabouts) for some period (see below).

The graph helps us understand why the current malaise in the US is not structural in nature. If the persistently high US unemployment was mostly structural then real GDP growth would not have fallen off the cliff as it did in early 2008. Structural deterioration is gradual and cumulative not sudden and sharp.

In the blog cited above I discuss the comparisons of my output gap measure with that produced by the US Congressional Budget Office. The magnitude of the output gaps produced are similar (although their measure improves much more quickly for reasons explained in the cited blog).

In our 2008 book – Full Employment abandoned – we provide an extensive critique of the standard approach to output gap measurement along the lines of the CBO methodology (which uses the NAIRU concept). You can also read an earlier working paper I wrote – The unemployed cannot find jobs that are not there! which documents the problems that are encountered when relying on the rubbery NAIRU concept for policy advice.

My output gap measure is also very similar to that produced by the Washington Post in the above graphic!

There is a reason that I bolded the phrase – for some period – in the above text, when discussing my output gap graph.

This relates to the phenomenon of hysteresis. Mike Konczal notes that the factors that lead to economies becoming stuck at below-full employment equilibrium states is also related to the “crucial concept of hysteresis – the idea that short-run recessions can lead to long-run damage to the economy”.

He claims it is an “an area where the Old and New Keynesian overlap”. I disagree with that statement. While some New Keynesians have acknowledged that the supply-side is not independent of the demand-side, the main models used in textbooks and policy advice continue to cast the supply-side of the economy as following a long-run trajectory which is independent of where the economy is at any point in time in terms of actual demand and activity.

I do not think he really gets to the point of hysteresis a topic which my PhD was initially focused on.

Hysteresis is a term drawn from physics and is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as :

… the phenomenon in which the value of a physical property lags behind changes in the effect causing it, as for instance when magnetic induction lags behind the magnetizing force.

In economics, we sometimes say that where we are today is a reflection of where we have been. That is, the present is path-dependent.

The point of my early work in the mid-1980s was that I argued (against the mainstream) that many perceived “structural imbalances” were, in fact, of a cyclical nature. Accordingly, a prolonged recession may create conditions in the labour market which mimic structural imbalance but which can be redressed through aggregate policy without fuelling inflation.

The mainstream orthodoxy at the time positive that the persistently high unemployment was the result of supply-side shifts in the labour market – for example, changing attitudes of workers to search intensity (that is, workers were lazy and preferred to take subsidised leisure in the form of income support payments from government) – and that aggregate demand policies aiming to stimulate the economy would not reduce this unemployment.

Accordingly, micro economic reform was necessary in the form of attacks on welfare payments to the unemployed (for example, increased stringency of activity tests) if governments wished to reduce unemployment.

My conjecture at the time was that any structural constraints that emerge during a large recession (for example, skill mismatched) can be wound back by strong fiscal policy stimulation.

For example, recessions cause unemployment to rise and due to their prolonged nature the short-term joblessness becomes entrenched long-term unemployment. The unemployment rate behaves asymmetrically with respect to the business cycle which means that it jumps up quickly but takes a long time to fall again.

There is robust evidence pointing to the conclusion that a worker’s chance of finding a job diminishes with the length of their spell of unemployment. When there is a deficiency of aggregate demand, employers use a range of screening devices when they are hiring. These screening mechanisms effectively “shuffle” the unemployed queue.

Among other things, firms increase hiring standards (for example, demand higher qualifications than are necessary) and may engage in petty prejudice.

A common screen is called statistical discrimination whereby the firms will conclude, for example, that because, on average, a particular demographic cohort has higher absentee rates (for example), every person from that group must therefore share those negative characteristics. Personal characteristics such as gender, age, race and other forms of discrimination are used to shuffle the disadvantaged workers from the top of the queue.

The long-term unemployed are also considered to be skill-deficient and firms are reluctant to offer training because they have so many workers to choose from.

But to understand what happens during a recession we need to consider the cyclical labour market adjustments that occur.

The hysteresis effect describes the interaction between the actual and equilibrium unemployment rates. The significance of hysteresis is that the unemployment rate associated with stable prices, at any point in time should not be conceived of as a rigid non-inflationary constraint on expansionary macro policy. The equilibrium rate itself can be reduced by policies, which reduce the actual unemployment rate.

The idea is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reserved. Structural imbalance refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to present themselves as an effective excess supply.

The non-wage labour market adjustment that accompany a low-pressure economy, which could lead to hysteresis, are well documented. Training opportunities are provided with entry-level jobs and so the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall. New entrants are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns) and redundant workers face skill obsolescence. Both groups need jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

In a recession, many firms disappear all together, particularly those who were using very dated capital equipment that was less productive and hence subject to higher unit costs than the best practice technology.

The skills associated with using that equipment become obsolete as it is scrapped. This phenomenon is referred to as skill atrophy. Skill atrophy relates not only to the specific skills needed to operate a piece of equipment or participate in a firm-specific process.

Long-term unemployment also erodes more general skills as the psychological damage of unemployment impacts on a worker’s confidence and bearing. A lot of information about the labour market is gleaned informally via social networks and there is strong evidence pointing to the fact that as the duration of unemployment becomes longer the breadth and quality of an unemployed worker’s social network falls.

Further, as training opportunities are typically provided with entry-level jobs it follows that the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall.

New entrants to the labour force – into the unemployment pool because of a lack of jobs – are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns).

As a result, both groups of workers – those made redundant and the new entrants – need to find jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

Therefore, workers enduring shorter spells of unemployment, other things equal, will tend to be more to the front of the queue. Firms form the view that those who are enduring long-term unemployed are likely to be less skilled than those who have just lost their jobs and with so many workers to choose from firms are reluctant to offer any training.

However, just as the downturn generate these skill losses, a growing economy will start to provide training opportunities as the unemployment queue diminishes. This is one of the reasons that economists believe it is important for the government to stimulate economic growth when a recession is looming to ensure that the skill transitions can occur more easily.

The long-run is thus never independent of the state of aggregate demand in the short-run. There is no invariant long-run state that is purely supply determined.

By stimulating output growth now, governments also help relieve longer-term constraints on growth – investment is encouraged and workers become more mobile.

The supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken. Hysteresis means that where you are today is a function of where you were yesterday and the day before that.

However, the longer a recession (that is, the output gap) persists the broader the negative hysteretic forces become. At some point, the productive capacity of the economy starts to fall (supply-side) towards the sluggish demand-side of the economy and the output gap closes at much lower levels of economic activity.

This is a point that Mike Konczal does not really come to grips with.

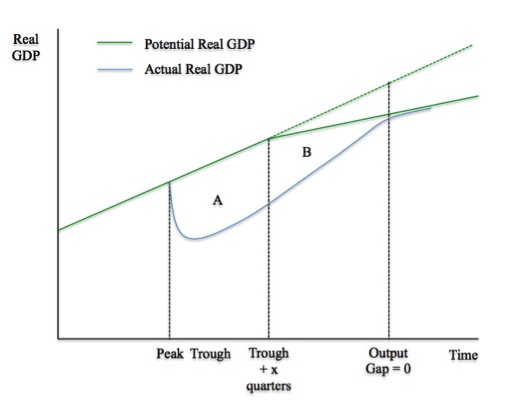

The following diagram shows how the demand-side and supply-sides interact following a recession to and find the long-run losses. Unlike the mainstream macroeconomics approach, which assumes that the “long-run” is supply-determined and invariant to the demand conditions in the economy at any point in time, the diagram shows that the supply-side of the economy responds to particular demand conditions.

There is a whole literature on the measurement of so-called sacrifice ratios, which attempt to measure the real GDP losses arising from deflationary monetary policy. Please read my blog – The Great Moderation myth – for more discussion on this point.

In relation to today’s blog, I abstract from that literature.

In terms of the following diagram, the potential output path is denoted by the green solid line noting the dotted green segment for later discussion. This is the level of real output it would be forthcoming if only available collective capacity (including Labour and equipment) was being fully utilised.

The potential real GDP assumes some constant growth in productive capacity driven by a smooth investment trajectory up until the point where it slow flattens.

If we assume that at the peak the economy was working at full capacity – that is, there was no output gap – then we can tell a story of what happens following an aggregate demand failure. The solid blue line is the actual path of real GDP.

You can see that the output gap opens up quickly as real GDP departs from the potential real GDP line. The area A measures the real output gap for the first x-quarters following the Trough. As the economy starts growing again as aggregate demand starts to recover (perhaps on the back of a fiscal stimulus, perhaps as consumption or net exports improve) after the Trough, the real output gap start to close.

however, the persistence of the output gap over this period starts to undermine investment plans as firms become pessimistic about the future state of aggregate demand. At some point, investment starts to decline and two things are observed: (a) the recovery in real output does not accelerate due to the constrained private demand; and (b) the supply-side of the economy (potential) starts to respond (that is, is influenced) by the path of aggregate demand takes over time.

Hysteresis means that where you are today is a function of where you were yesterday and the day before that. The pessimism by firms begins to reduce the potential real output of the economy (denoted by the divergence between the solid green line and the dotted green line).

The area B denotes a declining output gap arising from both these demand-side and supply-side effects. At some point, actual real output reaches potential real output – meaning the output gap is closed – but the overall growth rate is much lower than would have been the case if the economy has continued on its previous real output potential trajectory.

The entrenched recession is thus not only caused major national income losses while the output gap was open but is also made that the growth in national income possible in this economy is much lower and the nation, in material terms, is poorer as a consequence.

Moreover, the inflation barrier (that is, the point at which nominal aggregate demand is greater than the real capacity of the economy to absorb it) occurs at lower actual real output levels.

The estimated costs of the recession and fiscal austerity are much larger than the mainstream will ever admit. The point of the diagram is that the supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken.

Those who advocate austerity and the massive short-term costs that accompany it fail to acknowledge these inter-temporal costs.

Conclusion

What the hysteresis literature – both theoretical and applied – teaches us is that governments should do everything within their capacity to avoid recessions.

Not only does a strategy of early policy intervention avoid massive short-run income losses and the sharp rise in unemployment that accompany recession, but the longer term damage to the supply capacity of the economy and the deterioration in the quality of the labour force can also be avoided.

A national, currency-issuing government can always provide sufficient aggregate spending in a relatively short period of time to offset a collapse in non-government spending, which, if otherwise ignored, would lead to these damaging short-run and long-run consequences.

The “waiting for the market to work” approach is vastly inferior and not only ruins the lives of individuals who are forced to disproportionately endure the costs of the economic downturn, but, also undermines future prosperity for their children and later generations.

Murdoch explaining our change of government

I might write At the federal election results last weekend, which saw the government change to the (conservative) Liberal-National coalition from the (conservative) Labor Party.

Neither of the main parties respect human rights (witness the policies with respect to refugees where they both lock up young children indefinitely in tropical prisons knowing that the onset of mental illness as a result is a given).

Further, neither of the main parties considers they are responsible for the achievement and maintenance of full employment and both are happy to use unemployment as a tool to redistribute real income to profits to fund the excesses of the “top-end-of-town”.

Both of the main parties are so infested with neo-liberalism that it’s difficult to tell them apart. That is a slight simplification and I might write about the impacts of the change of government where there are notable differences, for example, their respective approaches to building public infrastructure relating to broadband technologies.

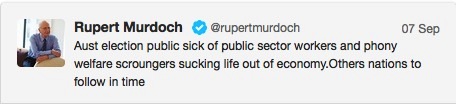

However, for those who didn’t see the twittering from that idiot Rupert Murdoch, this was his initial reaction to the election result:

Nice guy!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill, the Guardian today had a piece about Abbott. It contended that the Mad Monk was possibly the first Australian PM to win by attrition. Apparently, he doesn’t mind unions but draws the line at crooked ones. Really!! He doesn’t look too good from the UK.

I did notice the tweet by that *&%$#@, Murdoch. Not unexpected, is it.

Re the green line: I have always thought that linear lines of this sort were unrealistic and ought to be replaced by ogives, or S curves. This is the sort of curve that railway development in the Soviet Union exemplified. And it makes sense in empirical terms. It is quite common in ecological analyses, for instance in population growth curves, taking into account the differences between r-selected and K-selected species.

Yah, all them lazy moochers! Can’t they just run the newspaper empire they inherited from their dads and put their expensive private educations to use?

I think our biggest problem for the next few years is going to be a government that says it offers “work not welfare”, cuts welfare, but does nothing much to increase the work. It’s incredibly frustrating to know that the government can eliminate unemployment if it chooses but it doesn’t choose to, and wastes a huge amount of energy on blaming the unemployed, as though they are all lounging around on the lavish dole Australia provides.

Ghana’s real GDP is growing at 7% pa despite the central bank having a high inflation target of 9% pa, a budget deficit that’s 12.5% of GDP, and a current account deficit that’s 11.71% of GDP.

http://screencast.com/t/9ulELVx2Ql8Z

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-08-23/socgen-sees-ghana-inflation-to-less-gold-cash-speeding-cedi-fall.html

IMF is pressuring booming Ghana to reduce its budget deficit and then giving a GDP growth rate forecast of 8%.

http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/06/27/ghana-imf-idUSL5N0F344620130627

Total madness.