Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – August 24, 2013 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Start from a situation where the external balance is the equivalent of 2 per cent of GDP and the budget surplus is 2 per cent. If the budget balance stays constant and the external balance rises to the equivalent of 4 per cent of GDP then:

(a) National income rises and the private surplus moves from 4 per cent of GDP to 6 per cent of GDP.

(b) National income remains unchanged and the private surplus moves from 4 per cent of GDP to 6 per cent of GDP.

(c) National income falls and the private surplus moves from 4 per cent of GDP to 6 per cent of GDP.

(d) National income rises and the private surplus moves from 0 per cent of GDP to 2 per cent of GDP.

(e) National income remains unchanged and the private surplus moves from 0 per cent of GDP to 2 per cent of GDP

(f) National income falls and the private surplus moves from 0 per cent of GDP to 2 per cent of GDP.

The answer is Option (d) National income rises and the private surplus moves from 0 per cent of GDP to 2 per cent of GDP.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. But it also requires some understanding of the behavioural relationships within and between these sectors which generate the outcomes that are captured in the National Accounts and summarised by the sectoral balances.

We know that from an accounting sense, if the external sector overall is in deficit, then it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the accounting rules.

The important point is to understand what behaviour and economic adjustments drive these outcomes.

So here is the accounting (again). The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

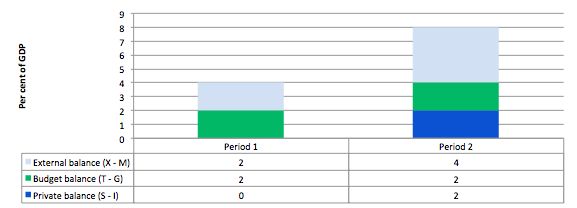

Consider the following graph and accompanying table which depicts two periods outlined in the question.

In Period 1, with an external surplus of 2 per cent of GDP and a budget surplus of 2 per cent of GDP the private domestic balance is zero. The demand injection from the external sector is exactly offset by the demand drain (the fiscal drag) coming from the budget balance and so the private sector can neither net save or spend more than they earn.

In Period 2, with the external sector adding more to demand now – surplus equal to 4 per cent of GDP and the budget balance unchanged (this is stylised – in the real world the budget will certainly change), there is a stimulus to spending and national income would rise.

The rising national income also provides the capacity for the private sector to save overall and so they can now save 2 per cent of GDP.

The fiscal drag is overwhelmed by the rising net exports.

This is a highly stylised example and you could tell a myriad of stories that would be different in description but none that could alter the basic point.

If the drain on spending (from the public sector) is more than offset by an external demand injection, then GDP rises and the private sector overall saving increases.

If the drain on spending from the budget outweighs the external injections into the spending stream then GDP falls (or growth is reduced) and the overall private balance would fall into deficit.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 2:

Taxes do not fund government spending but they do create unemployment.

The answer is True.

First, to clear the ground we state clearly that a sovereign government is the monopoly issuer of the currency and is never revenue-constrained. So the question is not about the tax revenue per se but rather the role taxes play in the monetary system. A sovereign government never has to “obey” the constraints that the private sector always has to obey.

The foundation of many mainstream macroeconomic arguments is the fallacious analogy they draw between the budget of a household/corporation and the government budget. However, there is no parallel between the household (for example) which is clearly revenue-constrained because it uses the currency in issue and the national government, which is the issuer of that same currency.

The choice (and constraint) sets facing a household and a sovereign government are not alike in any way, except that both can only buy what is available for sale. After that point, there is no similarity or analogy that can be exploited.

Of-course, the evolution in the 1960s of the literature on the so-called government budget constraint (GBC), was part of a deliberate strategy to argue that the microeconomic constraint facing the individual applied to a national government as well. Accordingly, they claimed that while the individual had to “finance” its spending and choose between competing spending opportunities, the same constraints applied to the national government. This provided the conservatives who hated public activity and were advocating small government, with the ammunition it needed.

So the government can always spend if there are goods and services available for purchase, which may include idle labour resources. This is not the same thing as saying the government can always spend without concern for other dimensions in the aggregate economy.

For example, if the economy was at full capacity and the government tried to undertake a major nation building exercise then it might hit inflationary problems – it would have to compete at market prices for resources and bid them away from their existing uses.

In those circumstances, the government may – if it thought it was politically reasonable to build the infrastructure – quell demand for those resources elsewhere – that is, create some unemployment. How? By increasing taxes.

So to answer the question correctly, you need to understand the role that taxes play in a fiat currency system.

In a fiat monetary system the currency has no intrinsic worth. Further the government has no intrinsic financial constraint. Once we realise that government spending is not revenue-constrained then we have to analyse the functions of taxation in a different light. The starting point of this new understanding is that taxation functions to promote offers from private individuals to government of goods and services in return for the necessary funds to extinguish the tax liabilities.

In this way, it is clear that the imposition of taxes creates unemployment (people seeking paid work) in the non-government sector and allows a transfer of real goods and services from the non-government to the government sector, which in turn, facilitates the government’s economic and social program.

The crucial point is that the funds necessary to pay the tax liabilities are provided to the non-government sector by government spending. Accordingly, government spending provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

So it is now possible to see why mass unemployment arises. It is the introduction of State Money (government taxing and spending) into a non-monetary economics that raises the spectre of involuntary unemployment. As a matter of accounting, for aggregate output to be sold, total spending must equal total income (whether actual income generated in production is fully spent or not each period). Involuntary unemployment is idle labour offered for sale with no buyers at current prices (wages).

Unemployment occurs when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account, but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns, other things equal. As a result, involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services translates into decreased output and employment. In this situation, nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless those cuts somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save, and thereby increase spending.

The purpose of State Money is for the government to move real resources from private to public domain. It does so by first levying a tax, which creates a notional demand for its currency of issue. To obtain funds needed to pay taxes and net save, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed units of the currency. This includes, of-course, the offer of labour by the unemployed. The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

This analysis also sets the limits on government spending. It is clear that government spending has to be sufficient to allow taxes to be paid. In addition, net government spending is required to meet the private desire to save (accumulate net financial assets). From the previous paragraph it is also clear that if the Government doesn’t spend enough to cover taxes and desire to save the manifestation of this deficiency will be unemployment.

Keynesians have used the term demand-deficient unemployment. In our conception, the basis of this deficiency is at all times inadequate net government spending, given the private spending decisions in force at any particular time.

So the answer should now be obvious. If the economy is to fulfill its political mandate it must be able to transfer real productive resources from the private sector to the public sector. Taxation is the vehicle that a sovereign government uses to “free up resources” so that it can use them itself. But taxation has nothing to do with “funding” of the government spending.

To understand how taxes are used to attenuate demand please read this blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- The budget deficits will increase taxation!

- Will we really pay higher taxes?

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Functional finance and modern monetary theory

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

Question 3:

Some progressives call for bank lending to be more closely regulated to ensure that all bank loans were backed by reserves held at the bank to stop another credit binge. However, financial market interests argue that this would unnecessarily reduce the capacity of the banks to lend and damage the economy. Both are wrong.

The answer is True.

In a “fractional reserve” banking system of the type the US runs (which is really one of the relics that remains from the gold standard/convertible currency era that ended in 1971), the banks have to retain a certain percentage (10 per cent currently in the US) of deposits as reserves with the central bank. You can read about the fractional reserve system from the Federal Point page maintained by the FRNY.

Where confusion as to the role of reserve requirements begins is when you open a mainstream economics textbooks and “learn” that the fractional reserve requirements provide the capacity through which the private banks can create money. The whole myth about the money multiplier is embedded in this erroneous conceptualisation of banking operations.

The FRNY educational material also perpetuates this myth. They say:

If the reserve requirement is 10%, for example, a bank that receives a $100 deposit may lend out $90 of that deposit. If the borrower then writes a check to someone who deposits the $90, the bank receiving that deposit can lend out $81. As the process continues, the banking system can expand the initial deposit of $100 into a maximum of $1,000 of money ($100+$90+81+$72.90+…=$1,000). In contrast, with a 20% reserve requirement, the banking system would be able to expand the initial $100 deposit into a maximum of $500 ($100+$80+$64+$51.20+…=$500). Thus, higher reserve requirements should result in reduced money creation and, in turn, in reduced economic activity.

This is not an accurate description of the way the banking system actually operates and the FRNY (for example) clearly knows their representation is stylised and inaccurate. Later in the same document they they qualify their depiction to the point of rendering the last paragraph irrelevant. After some minor technical points about which deposits count to the requirements, they say this:

Furthermore, the Federal Reserve operates in a way that permits banks to acquire the reserves they need to meet their requirements from the money market, so long as they are willing to pay the prevailing price (the federal funds rate) for borrowed reserves. Consequently, reserve requirements currently play a relatively limited role in money creation in the United States.

In other words, the required reserves play no role in the credit creation process.

The actual operations of the monetary system are described in this way. Banks seek to attract credit-worthy customers to which they can loan funds to and thereby make profit. What constitutes credit-worthiness varies over the business cycle and so lending standards become more lax at boom times as banks chase market share (this is one of Minsky’s drivers).

These loans are made independent of the banks’ reserve positions. Depending on the way the central bank accounts for commercial bank reserves, the latter will then seek funds to ensure they have the required reserves in the relevant accounting period. They can borrow from each other in the interbank market but if the system overall is short of reserves these “horizontal” transactions will not add the required reserves. In these cases, the bank will sell bonds back to the central bank or borrow outright through the device called the “discount window”.

At the individual bank level, certainly the “price of reserves” will play some role in the credit department’s decision to loan funds. But the reserve position per se will not matter. So as long as the margin between the return on the loan and the rate they would have to borrow from the central bank through the discount window is sufficient, the bank will lend.

So the idea that reserve balances are required initially to “finance” bank balance sheet expansion via rising excess reserves is inapplicable. A bank’s ability to expand its balance sheet is not constrained by the quantity of reserves it holds or any fractional reserve requirements. The bank expands its balance sheet by lending. Loans create deposits which are then backed by reserves after the fact. The process of extending loans (credit) which creates new bank liabilities is unrelated to the reserve position of the bank.

The major insight is that any balance sheet expansion which leaves a bank short of the required reserves may affect the return it can expect on the loan as a consequence of the “penalty” rate the central bank might exact through the discount window. But it will never impede the bank’s capacity to effect the loan in the first place.

The money multiplier myth leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted hometo the “government” (the central bank in this case).

The reality is that the reserve requirements that might be in place at any point in time do not provide the central bank with a capacity to control the money supply.

So would it matter if reserve requirements were 100 per cent? In this blog – 100-percent reserve banking and state banks – I discuss the concept of a 100 per cent reserve system which is favoured by many conservatives who believe that the fractional reserve credit creation process is inevitably inflationary.

There are clearly an array of configurations of a 100 per cent reserve system in terms of what might count as reserves. For example, the system might require the reserves to be kept as gold. In the old “Giro” or “100 percent reserve” banking system which operated by people depositing “specie” (gold or silver) which then gave them access to bank notes issued up to the value of the assets deposited. Bank notes were then issued in a fixed rate against the specie and so the money supply could not increase without new specie being discovered.

Another option might be that all reserves should be in the form of government bonds, which would be virtually identical (in the sense of “fiat creations”) to the present system of central bank reserves.

While all these issues are interesting to explore in their own right, the question does not relate to these system requirements of this type. It was obvious that the question maintained a role for central bank (which would be unnecessary in a 100-per cent reserve system based on gold, for example.

It is also assumed that the reserves are of the form of current current central bank reserves with the only change being they should equal 100 per cent of deposits.

We also avoid complications like what deposits have to be backed by reserves and assume all deposits have to so backed.

In the current system, the the central bank ensures there are enough reserves to meet the needs generated by commercial bank deposit growth (that is, lending). As noted above, the required reserve ratio has no direct influence on credit growth. So it wouldn’t matter if the required reserves were 10 per cent, 0 per cent or 100 per cent.

In a fiat currency system, commercial banks require no reserves to expand credit. Even if the required reserves were 100 per cent, then with no other change in institutional structure or regulations, the central bank would still have to supply the reserves in line with deposit growth.

Now I noted that the central bank might be able to influence the behaviour of banks by imposing a penalty on the provision of reserves. It certainly can do that. As a monopolist, the central bank can set the price and supply whatever volume is required to the commercial banks.

But the price it sets will have implications for its ability to maintain the current policy interest rate but that is another matter.

The central bank maintains its policy rate via open market operations. What really happens when an open market purchase (for example) is made is that the central bank adds reserves to the banking system. This will drive the interest rate down if the new reserve position is above the minimum desired by the banks. If the central bank wants to maintain control of the interest rate then it has to eliminate any efforts by the commercial banks in the overnight interbank market to eliminate excess reserves.

One way it can do this is by selling bonds back to the banks. The same would work in reverse if it was to try to contract the money supply (a la money multiplier logic) by selling government bonds.

The point is that the central bank cannot control the money supply in this way (or any other way) except to price the reserves at a level that might temper bank lending.

So if it set a price of reserves above the current policy rate (as a penalty) then the policy rate would lose traction.

The fact is that it is endogenous changes in the money supply (driven by bank credit creation) that lead to changes in the monetary base (as the central bank adds or subtracts reserves to ensure the “price” of reserves is maintained at its policy-desired level). Exactly the opposite to that depicted in the mainstream money multiplier model.

The other fact is that the money supply is endogenously generated by the horizontal credit (leveraging) activities conducted by banks, firms, investors etc – the central bank is not involved at this level of activity.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

“Taxes do not fund government spending but they do create unemployment.”

Unless we assume ceteris paribus I would say taxes can create unemployment is correct. Not do create UE. Taxes reduce money in circulation and decrease demand but that is only one factor out of many in the economy contributing to AD. Other factors such as increased productivity could be increasing demand and employment at a greater rate than the drag from taxation.

Bill,

I assume the “progressives” referred to in question 3 are advocates of full reserve banking, like Laurence Kotlikoff, Mathew Klein, Positive Money, etc. For Klein, see:

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-03-27/the-best-way-to-save-banking-is-to-kill-it.html

Your argument is based on the idea that full reserve consists simply of taking the existing system (which imposes for example a 10% reserve requirement on large banks in the US) and upping the figure to 100%. Full reserve actually involves a totally different set of rules for banking, roughly as follows.

Two types of account are available to depositors: first a 100% safe transaction account where, 1, money deposited is not loaned on or invested, 2, the account is fully backed by reserves and is government backed, and 3, no interest is paid. Second, there are accounts where money IS LOANED ON. Those do pay interest, and they are not backed by government. Plus under Kotlikoff and Klein’s systems, the loans are not backed by reserves. Plus the value of depositors’ stakes varies with the performance of the underlying loans or investments. In the case of Kotlikoff’s system, anyone wanting their money loaned on by their bank just buys into a unit trust / mutual fund of their choice.

That system has several merits. First, it’s impossible for banks to suddenly go bust. So credit crunches of the type we had five years ago are ruled out or ameliorated. For more on that, see this WSJ article by John Cochrane:

http://www.hoover.org/news/daily-report/150171

Second, there is no longer any need for bank subsidies.

Third, credit binges are actually ameliorated. It’s true, as you suggest, that commercial banks under 100% reserve can still lend money into existence, or lend when they see a viable lending opportunity. But under the above rules, those banks have a problem as follows.

Money created by a commercial bank will inevitably get deposited in other banks, and a proportion of the latter depositors will want to put their money into safe accounts. That means they have to get hold of reserves. And the central bank controls reserve production. Ergo the central bank controls or has a big influence on the amount of credit or money creation done by commercial banks. Plus where depositors do for example get their bank to lend their money to mortgagors, those depositors foot the bill if the bank goes in for credit binge NINJA mortgages and it all goes belly up. And that’s a constraint on silly lending.

It is true, as you say, that central banks lose control of interest rates under the above sort of system. But the reaction of full reservers to that is “good riddance”. Some of the deficiencies in interest rate adjustment as a means of regulating the economy are set out in this work which advocates full reserve:

http://www.positivemoney.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/NEF-Southampton-Positive-Money-ICB-Submission.pdf

The latter work actually advocates controlling aggregate demand by a means which I think most MMTers agree with, i.e. simply having the government / central bank machine create and spend new money into the economy when stimulus is needed.

That’s like claiming sugar has nothing to do with tooth decay!

There are intermediate steps, but ultimately it accounts for most of it.

Aidan,

“There are intermediate steps, but ultimately it accounts for most of it.”

To see why taxes don’t “fund” government spending, you need to take an extreme example:

Let’s say that a country has a serious deflation problem. Infact, prices and wages are falling at 30% per year. So there is absolutely no inflation problem on the horizon.

Let’s also say that temporarily there is plenty of demand for the currency because there are lots of people with debts denominated in that currency which they have to repay, and such that taxation is not required to create any extra demand for the currency.

In this instance it is entirely possible for the government give a 100% tax break to everyone for the year.

All that happens then is the budget deficit has risen equivalent to the tax break, and the government is still spending despite the lack of tax revenue.

So tax revenue is not required in order for a government to spend.

Kind Regards

Aidan,

“That’s like claiming sugar has nothing to do with tooth decay!”

Yet there is a direct causal link between sugar and tooth decay. There is no such direct causal link between governments taxing and governments spending.

Bill, it would be great if there’s some space in the blog next week to talk about the reports of a gathering economic crisis in India from an MMT perspective. It’s a pretty different situation from the first-world economic problems you generally blog about, and it’s an example where a trade deficit seems to be causing major issues in a country which has its own currency even though most of your writing about the US say has stressed that this isn’t the real problem (maybe it isn’t here either?). Furthermore I’ve seen at least one commentator partly blame the rural jobs scheme which you’ve championed.

CharlesJ –

Your extreme example merely shows that taxes aren’t the only thing that can fund government spending. That’s something I never disputed in the first place.

FWIW sugar isn’t the only cause of tooth decay either – just the main cause.

Aidan, what exactly do you mean when you use the word ‘fund’?

As I understand it, taxes enable spending in that they make room in the real economy for the governemnt to purchase goods and services without increasing inflation. The government doesn’t need the money from the taxes; it needs the real goods and services to be available because the private sector doesn’t have the money to purchase them. Given the various multipliers, the relationship between the amount of money drained by taxation and the amount of spending enabled isn’t likely to be 1:1, or even stable for any length of time.

FlimFlamMan

“Given the various multipliers, the relationship between the amount of money drained by taxation and the amount of spending enabled isn’t likely to be 1:1, or even stable for any length of time.”

Weird, I only just realised that aspect today as I was walking home from the shops.

Sorry Bill, not to nitpick but Question 2 is false, because you did not differentiate between governments that issue their own currency, and those that dont (state, locals, Eurozone). This is an important difference that should be noted anytime we discuss MMT, because eventually the “we are becoming Greece” line will come up.

I got that answer wrong because I thought you were testing us with a trick question 😉