I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Australia output gap – not close to full capacity

A national media organisation (Crikey) invited me to be one of their Fantasy Budget providers this year and this is a background blog to the preparation of my Fantasy Budget 2013-14 for Australia, which I will publish next Monday. In this blog I consider the state of the Australian economy in terms of output gaps. The Australian government is keen to claim that the economy is operating close to or at trend real output – sometimes the Prime Minister or Treasurer – and senior Treasury officials, will replace the descriptor “trend output” with “full employment”. They make that claim to justify imposing fiscal austerity on the economy, which is expressed by their most recent goal to achieve a budget surplus in the current year. They have been pursuing that strategy for several budgets now after taking appropriate steps in 2008 to allow the budget deficit to rise significantly to head off the looming disaster associated with the global financial crisis. While the stimulus was not large enough at the time it did save the economy from the type of chronic recession that most of the advanced world remains stuck in. But, once recovery was established, the conservative ideology returned and the fiscal stimulus was withdrawn too quickly and an austerity plan implemented. At the time, it was clear that they would fail to achieve a surplus because in attempting to do so they undermined the recovery, and, their tax revenue growth. Other international events (a slowing of the terms of trade and an overvalued dollar) have compounded their poorly crafted fiscal strategy. The reality is that the Australian economy is now performing well below trend and the divergence is increasing. The labour market is also producing grossly inferior outcomes and we are clearly a hundreds of thousands of jobs short of what a reasonable definition of full employment would require. The budget deficit is too small not too large and the direction of policy in the coming year should be expansionary not contractionary.

The complete suite of Fantasy Budget blogs are as follows:

- The indecent inconsistency of the neo-liberals

- Australia output gap – not close to full capacity

- Daily macroeconomic income losses from unemployment

- The Australian labour market – 815 thousand jobs from full employment

- What is a Job Guarantee?

- Investing in a Job Guarantee – how much?

- MMT Budgetary Principles

- The Fantasy Budget 2013-14

Introduction

The Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2012-13 – which is published by the Federal government each year in December to update the progress outlined in the May Budget, was delivered somewhat earlier last year (October 22, 2012). Speculation was that the Government knew its mining tax revenue was going to come in well below expectations and wanted to make this statement before that news was made official.

In the Introduction to the MYEFO the Government said:

The Government is returning the budget to surplus in 2012‑13, notwithstanding a weaker global economy that has weighed heavily on tax receipts. Returning to surplus is appropriate given current economic conditions, with the economy forecast to grow around trend, the unemployment rate forecast to remain low and commodity prices remaining high by historical standards.

For example, in the national ABC Current Affairs 7.30 segment, the night the MYEFO was released – Federal Treasurer outlines economic outlook – the Federal Treasurer Wayne Swan was asked whether it was the Government’s intention to “return a budget surplus next year at any costs” said that pursuing a surplus was a sound fiscal strategy for Australia:

Because we think that’s the appropriate setting when your growth is around trend, when you’ve got low unemployment, when you’ve got a strong investment pipeline and when you’ve got contained inflation.

The Government has continually been claiming that the economy is growing around trend and that there is low unemployment. Those claims have also clearly framed the federal budgetary process over the last two to three fiscal years. It has been the Treasurer’s regular mantra, sometimes augmented with the claim that Australia is operating at around full employment.

More recently, in a – Keynote Presentation – to the National Conference of the Australian Workers’ Union in Brisbane on February 19, 2013, the Federal Treasurer said that the Australian government was channelling the glorious days of the Curtin Labor Government. He said:

The victory of 1943 led to a great era of advance for the country that gave us full employment … The lesson here is simple: in a time of trouble, you still need to keep an eye on the future, laying the foundations to build a better economy and better society. That’s what our government is doing now.

The reality is very different from what the Treasurer has chosen to portray. The differences are so stark that it is clear that the current pro-cyclical budget strategy pursued by the Government has been deeply flawed and damaging to the opportunities for Australians to gain work and enjoy national income growth.

In fact, the correct budget strategy, to suit the times and the behaviour and signalled intentions of the other major macroeconomic sectors – the external sector and the private domestic sector – is exactly the opposite to that being pursued by the current Government.

The government should seek to expand the budget deficit to close the current output gap, which stands at between 4.5 to 5 per cent of potential (trend) real GDP.

Estimating the Output Gap

In the Australian Senate Standing Committee on Economics – Questions on Notice (May 29-31, 2012), the Treasury was – Questioned – by the Queensland Greens Senator Larissa Waters about the Government’s obsession with achieving a budget surplus in the coming fiscal year.

Among other things, the Senator asked:

The OECD’s latest Economic Outlook estimated that there is an ‘output gap’ of around 2 per cent of GDP in Australia; that GDP is below trend. Why then is there an economic need for a contractionary fiscal policy?

The Senator’s questions were dismissed by the Treasury in the hearing in this way:

These issues have been addressed in the Secretary’s Annual post-Budget Address to the Australian Business Economists on 15 May 2012.

Please read my blog – The current and former Treasury boss speak – for a detailed discussion of the Treasury secretary’s address.

By way of summary, the Head of the Australian Treasury, Martin Parkinson delivered his traditional Annual post-Budget Address to the Australian Business Economists – Macroeconomic Policy for Changing Circumstances – in Sydney yesterday. You can download the Speech – should you prefer to read it off-line.

He outlined where the Treasury forecasts made in the 2011-12 Budget had failed to materialise (mostly excessive optimism regarding export growth – predicted 6.5 per cent against probably actual of 4 per cent – taking 1 per cent of total real GDP growth one you take into account the fact that imports will probably be higher than expected).

In relation to the planned fiscal austerity that the Government announced (to get the budget back into surplus despite a slowing economy), which was the objective of the Greens Senator’s question, the Treasury secretary said:

… let me make some general comments about the impact of discretionary fiscal policy on the macro-economy.

I have to admit that I am intrigued by the arguments put forward by a number of commentators on this issue. Obviously, it is not a new issue, with people arguing strenuously in recent years that the fiscal stimulus injected during the GFC had no impact on economic activity. For consistency, those same people presumably argue that that any fiscal consolidation must also have no impact on the macro-economy… [after some theoretical discussion and consideration of evidence he concluded]… In short, the standard Mundell-Fleming theory appears to hold under a specific set of conditions, but when these conditions are relaxed discretionary fiscal policy has significant real effects, and to suggest otherwise risks a triumph of ideology over experience.

This means that the Australian Treasury clearly thinks that the fiscal multipliers are “positive and sizeable” which runs in contradistinction to what a large number of the academic economists think. But then the latter are ruled almost entirely by ideology and refuse to adjust their position when the facts dictate otherwise.

Also recall the major admission by the IMF last October that they had dramatically underestimated the size of the expenditure multipliers.

Recall that Chapter 3 of the World Econmomic Outlook Update – published by the IMF in October 2010 – entitled – Will It Hurt? Macroeconomic Effects of Fiscal Consolidation – the IMF used estimates drawn from simulations of the IMF’s Global Integrated Monetary and Fiscal Model (GIMF) to tell nations that fiscal consolidation would inflict short-term damage of a relatively modest variety.

The estimated rise in net exports they predicted would “soften the contractionary impact” and fiscal consolidation had to be based on spending cuts rather than tax hikes because if the latter used the IMF told us that the consolidation would be “more painful”.

The IMF also said that there was “truth” in the ” “expansionary fiscal contractions hypothesis” because the cuts in government deficits would stimulate private sector business and household confidence, which would allow that sector to pick up the spending gaps left by the government withdrawals.

At worst, the IMF predicted that:

A fiscal consolidation equal to 1 percent of GDP typically reduces GDP by about 0.5 percent within two years and raises the unemployment rate by about 0.3 percentage point.

This sort of economic modelling led governments to impose harsh fiscal austerity on their economies. Three years later any country-by-country case study would tell us these forecasts were not even remotely correctly.

In this blog – So who is going to answer for their culpability? – I provide a detailed account of the IMFs blunder and its implications.

In short, they “discovered” that their policy advice, which has caused millions to become unemployed and nations to shed income and wealth in great proportions and all the rest of the austerity detritus, was based on errors in estimating the value of the expenditure multiplier.

They now believe that the modest contraction – 1 per cent equals 0.5 per cent is null and void. They now admit the expenditure multipliers may be up to around 1.7, which means that for every dollar of government spending, the economy produces $1.70 of national income. Under their previous estimates of the multiplier, a dollar of government spending would translate into only 50 cents national income (a bad outcome).

The renewed awareness from the arch-austerity merchants that they were wrong and that fiscal policy is, in fact, highly effective, means that the “fiscal consolidation” that they have been bullying nations to impose (successfully) will be highly damaging.

It means that the continued obsession not only with fiscal austerity but also with discussions surrounding monetary policy have been based on false premises. There have been many articles over the last few years expressing surprise that the vast monetary policy changes have had little effect.

This admission has major implications for the Australian government’s budget strategy, which I fear it is ignoring.

But it is also clear that the Australian Treasury has acknowledged the effectiveness of fiscal policy. In that context, the Treasury secretary, in his May 2012 address, acknowledged that his Department was consistent in its view and thus knew that the 2012-13 Budget would have “a contractionary effect on activity”. The question is how much of an effect.

In the 2012-13 Budget, introduced last May, the Australian Government announced one of the largest single-year fiscal shifts in our history which amounts to 3.1 per cent of GDP in 2012-13. The Treasury secretary correctly noted that the final impact (via the multipliers) depends on various factors including the (avoided) leakage from the domestic spending system (via imports).

In his analysis of the size of the real GDP contraction that the budget austerity will cause he repeated the Government’s mantra that the economy was close to full employment and growing around trend and concluded from that:

There are also those who argue that returning the budget to surplus in 2012-13 is a political gesture and there would be no great harm in delaying this by a year or so.

The problem with this argument is that if it’s not appropriate to restore the structural budget position when we have low unemployment and the economy is expected to grow at around trend, when will it be appropriate?

First, I will outline general fiscal policy principles in the Fantasy Budget 2013-14 document. I will point out that there is no necessity for the budget to be in surplus if the economy is growing on trend. Depending on the behaviour of the external sector and the private domestic sector, the structural budget position at “trend growth” could be a surplus or deficit (of varying magnitudes) or even a balance.

For example, for a nation with a current account deficit of say 2 per cent of GDP, and the private domestic sector spending exactly what it earns (S = I) and therefore not building indebtedness overall, the appropriate government balance would be a deficit of 2 per cent even if trend growth was being achieved.

In other words, the a particular budget balance should not be the target of policy because it is determined by both government spending and tax plans and the strength of private spending. The latter determines how much tax revenue the government earns for a given tax structure. There is nothing sacrosanct about a budget surplus in isolation from what is happening in non-government sector.

Second, the factual matter concerns whether the Australian economy is growing on trend and their is no output gap.

What are output gaps? The output gap is usually defined as the difference between actual and potential real GDP, expressed as a percentage of potential output. Many agencies publish estimates of output gaps for their countries. For example, the – US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) regularly puts out estimates of the GDP and unemployment gaps as part of their exercise in decomposing the federal budget outcome into cyclical (automatic stabilisers) and structural components.

The IMF World Economic Indicators and the OECD Economic Outlook publications, also publish multi-country estimates of the annual output gaps.

As I note in this blog – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – the problem is that the estimates of output gaps are extremely sensitive to the methodology employed.

They rely on an estimate of potential GDP, which is non-observable. It is clear that the typical methods used to estimate potential GDP reflect ideological conceptions of the macroeconomy, which are problematic when confronted with the empirical reality.

For example, on Page 3 of the CBO document – Measuring the Effects of the Business Cycle on the Federal Budget – we read:

… different estimates of potential GDP will produce different estimates of the size of the cyclically adjusted deficit or surplus …

CBO define Potential GDP as “the level of output that corresponds to a high level of resource … labor and capital … use.

So how do they estimate potential GDP? They explain their methodology in this document.

While the technicalities are not something I will go into in this blog – see my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned for the mathematical and econometric chapter and verse, suffice to say that they CBO uses the standard mainstream method.

CBO say that they:

They start with “a Solow growth model, with a neoclassical production function at its core, and estimates trends in the components of GDP using a variant of a tried-and-tested relationship known as Okun’s law. According to that relationship, actual output exceeds its potential level when the rate of unemployment is below the “natural” rate of unemployment) Conversely, when the unemployment rate exceeds its natural rate, output falls short of potential. In models based on Okun’s law, the difference between the natural and actual rates of unemployment is the pivotal indicator of what phase of a business cycle the economy is in.

The resulting estimate of Potential GDP is “an estimate of the level of GDP attainable when the economy is operating at a high rate of resource use” and that if “actual output rises above its potential level, then constraints on capacity begin to bind and inflationary pressures build” (and vice versa).

So despite saying that their estimate of Potential GDP is “the level of output that corresponds to a high level of resource … labor and capital … use” what you really need to understand is that it is the level of GDP where the unemployment rate equals some estimated NAIRU.

Intrinsic to the computation is an estimate of the so-called “natural rate of unemployment” or the Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment. This is the mainstream version of “full employment” but is, in fact, an unemployment rate which is consistent with a stable rate of inflation. Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on why the NAIRU is a flawed concept that should not be used for policy purposes.

Given the history of estimates of the NAIRU, the “steady-state” unemployment could be as high as 8 per cent or as low as 3 per cent. The former estimate would hardly be considered “”high rate of resource use”. Similarly, underemployment is not factored into these estimates

The concept of a potential GDP in the CBO parlance is thus not to be taken as a fully employed economy. Rather they use the standard dodge employed by mainstream economists where the the concept of full employment is not constructed as the number of jobs (and working hours) which satisfy the preferences of the available labour force but rather in terms of the unobservable NAIRU.

The problem is that policy makers then constrain their economies to achieve this (assumed) cyclically invariant benchmark. Yet, despite its centrality to policy, the NAIRU evades accurate estimation and the case for its uniqueness and cyclical invariance is weak. Given these vagaries, its use as a policy tool is highly contentious.

CBO say that their estimates of the NAIRU are derived from “historical relationship between the unemployment rate and changes in the rate of inflation”, in other words, a Phillips Curve. Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point.

In Full Employment abandoned we provide an extensive critique of the NAIRU concept. You can also read an earlier working paper I wrote – The unemployed cannot find jobs that are not there! which documents the problems that are encountered when relying on the rubbery NAIRU concept for policy advice.

The point is that the typical mainstream estimates the output gap usually understate the degree of slack in the economy, which then means that policy makers are biased towards adopting an excessively austere fiscal policy approach.

It also leads them to claim the economy is operating at near or at full employment, when in reality, the broad labour underutilisation indicators might be signalling massive wastage.

That is exactly the situation that prevails in Australia at present.

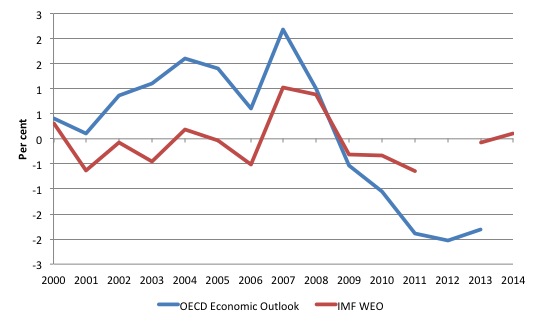

Figure 1 shows the estimates of the Australian output gap produced by the IMF and the OECD for the period 2000 to 2012 (with IMF estimates to 2014). The IMF World Economic Indicators currently has no estimate for 2012.

The OECD estimated that in 2012 the output gap was 2.03 per cent of potential, while the IMFs estimates would lie between 0.644 per cent of potential and 0.074 per cent of potential. The conclusion is that the OECD doesn’t think Australia is operating at capacity, while the IMF considers the economy to be at capacity (or close enough to it).

The IMF estimates do not bear up with the evidence that growth is currently well below its recent trend and the labour market is deteriorating rapidly. The IMF has an appalling record of forecasting – Please read my blog – The culpability lies elsewhere … always! – for more discussion on this point.

The question then is whether the OECD estimates are reliable or likely, as I have argued above to be underestimates of the degree of slack in the Australian economy.

Figure 1 Output Gap, Australia, IMF World Economic Indicators and OECD Economic Outlook, 2000 to 2012, Per cent of Potential

The RBA and Treasury talk about trend growth regularly and measure the state of the economy in relation to that concept. There are various ways in which one could measure the trend growth rate.

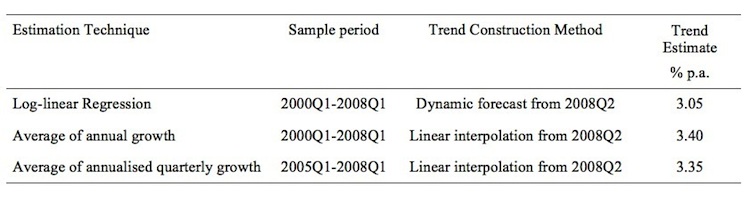

Table 1 summarises three methods that can be used to estimate the trend real GDP for Australia. You can see that the estimates of trend real GDP growth lie between 3.05 per cent per annum to 3.40 per cent per annum.

The RBA and Treasury have from time-to-time indicated they considered the trend growth rate to be between 3.1 and 3.5 per cent. So the ballpark figures expressed in Table 1 are consistent with the views of both major government institutions.

They would also suggest that the OECD estimates of potential growth are biased downwards. There is a difference between trend real GDP and potential real GDP but there is no evidence that the Australian economy has been regularly exceeding its potential over the last decade, which would tend to suggest that, at the very least, trend growth is closer to potential than the OECD’s estimates.

Table 1 Estimating Trend Growth, Australia

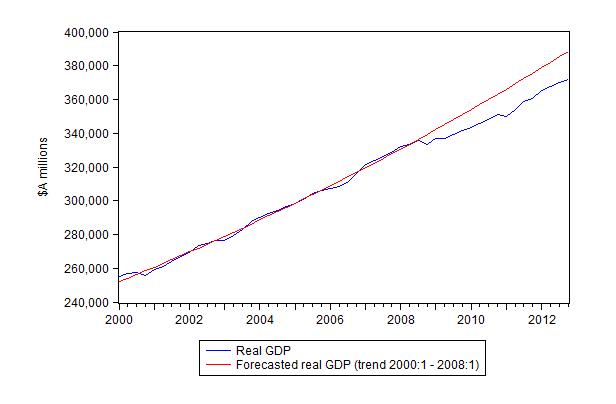

The rest of the analysis uses the regression analysis of trend. The method was standard. Real GDP was decomposed into its trend and cyclical components and for the period 2000Q1 to 2008Q1.

The estimated model was then forecast out-of-sample (dynamic) for the period 2008Q2 to the most recent observation 2012Q4. The forecasted trend series can be interpreted as telling us what would have happened to the evolution of real GDP if the GFC had not have occurred and the Government had not pursued its surplus obsession.

Figure 2 shows real GDP in Australia (Gross domestic product: Chain volume measure) for the period 2000Q1 to 2012Q4 (blue line) and estimated trend based on the log-linear regression (red line).

This model is entirely plausible and fits well with other data indicators that are available which I will consider in further background papers in the coming days.

Figure 2 Real GDP and Trend GDP, Australia, 2000Q1 to 2012Q4, $A millions

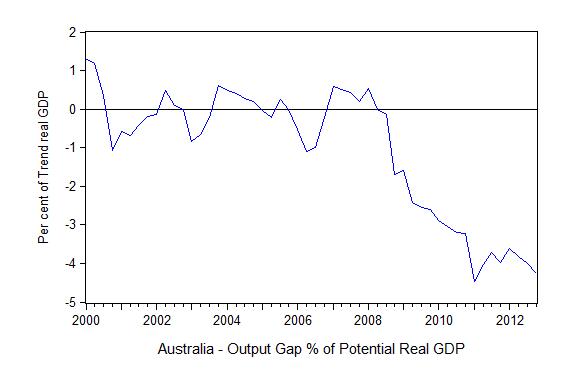

The gap between real GDP and trend GDP is not strictly an output gap because that would require the additional assumption that trend growth always defines the potential growth of the economy. An economy may be held in a state of austerity for years (as we are seeing in Europe at present) and its trend will be much lower than its potential – given that tens of thousands to millions of people might be persistently unemployed or underemployed.

So we should more accurately call the gap between real GDP and trend GDP to be an incremental output gap because it does not presume that the trend output upon which the forecast was based coincided with potential output or full employment.

In other words, the incremental output gap depicts the increase in whatever gap existed at the time the forecast began (March-quarter 2013).

With that qualification in mind, Figure 3 shows the incremental output gap (expressed as a percentage of trend real GDP) that is derived from the previous regression and forecasting exercise.

Figure 3 Output Gap, Australia, 2000Q1 to 2012Q4, Per cent of Trend

As at December 2012, the annual output gap was estimated to be around 3.9 per cent per cent or around $A60,229 million in lost annual output and income. As we will see in the labour market analysis, that gap could support enough labour-intensive jobs to restore full employment.

The quarterly estimate for December reveals a growing output gap of 4.5 per cent which will endure into 2013.

Conclusion

In the next Fantasy Budget 2013-14 background blog I will consider the degree of labour underutilisation in detail and provide estimates of the investment needed to implement a Job Guarantee in Australia.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

When the CBO estimated that deficit reduction policies would reduce GDP growth by one and a half percentage points, did they use the expenditure multiplier of .5 or 1.7?

Dear Bill,

Speaking of the output gap, have you seen the recent(ish) BIS paper “Rethinking potential output: Embedding information about the financial cycle” by Claudio Borio and colleagues? I came across it and had a quick look, and (in my ignorant opinion) the reasoning seems to be:

1. In the past when people tried to predict the future course of the economy, they neglected the influence of the financial sector.

2. Doh!

3. Including the financial sector, it is clear that you can have a bubble that doesn’t show up as inflation.

4. So moderate inflation is no guarantee that output is not beyond capacity.

5. Policy-makers should take this into account (presumably by implementing more restrictive monetary policy).

From the graphs accompanying the paper, the late Clinton era would be one period in which they would say output was above its natural level, so presumably you wouldn’t agree with their analysis? It’s a shame, because the BIS analysts seem to be somewhat more clued up than the average for the mainstream.

It is outrageous when the Treasurer says “when you’ve got low unemployment” as if to imply we currently have low unemployment. We don’t. This kind of revisionism annoys the heck out of me. Anyone who knows a bit of history knows that anything above approx. 2% (frictional) unemployment is too much unemployment.

One large structural change has been the entry of women into the workforce. Although the entry of women into the workforce since the 1960s (or even since WW2) has increased the total employment pool this should have no effect on unemployment. The extra potential and then actual employed persons means a commensurate increase in output and wages earnings as they are employed. This means a commensurate increase in aggregate demand.

The other large structural change is increasing mechanisation and automation. Again, the increase in productivity and aggregate output simple create more possibilites in human services; health, welfare and education. And also create more possibilities for ecological services and remediation work. Again, there is no excuse not the employ people.

The claim is made that higher public spending (via deficits) to soak up unemployment will cause unacceptable inflation. However, the case is that other main source of inflation, especially but not only of asset inflation, could be controlled by controlling debt creation by private lenders. The high profits of finance compared to the profit share of manufacture and primary prouction and compared to the income share of wages is the major real source of inflation. Given that much financial activity produces nothing (no goods, no services) and yet produces a large income for the operators and owners, and given that financial activity has grown exponentially and at a much faster rate than the general economy then this indicates the financial industry as the major source of inflationary pressure.

Unemployment is kept high as a deflationary counter to the inflationary pressure of the over-sized financial sector. We (the great majority) would be far better off if the over-sized financial sector was deflated and full employment policies were pursued.