I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The culpability lies elsewhere … always!

Two papers have come out in the first week of January that provide further evidential support for the argument that the majority of macroeconomics that is taught in standard university programs is worthless. The first (published January 3, 2013) – Growth Forecast Errors and Fiscal Multipliers – from the IMF attempts to explain why the planned fiscal austerity measures in advanced economies have been more damaging than mainstream economists predicted. It is an excruciating attempt at regaining credibility for the seriously wayward IMF. The problem is that its credibility is so far in deficit that it has a lot of consolidation to do before anyone should believe them again. The second paper (published January 2013) – A Boost in the Paycheck: Survey Evidence on Workers’ Response to the 2011 Payroll Tax Cuts – from researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York “presents new survey evidences on workers’ response to the 2011 payroll tax cuts”. The results of the survey? Much higher estimates of the consumption propensities than were predicated from mainstream economic theory. Implication? The standard theory taught to students is wrong and should be disregarded.

On the issue of forecasts, I am clearly not naive enough to argue that an error in a prediction is a sign that we should jettison the underlying theory or conceptual approach that produced the forecast. I am an econometrician after all who deals with probabilistic models each day.

All forecasts come with standard error bands because of the nature of the exercise. Those in the know understand that.

Indeed, this year I was invited to participate in the 2013 BusinessDay Survey which was run by the Fairfax Media (publishers of the Australian Financial Review, Sydney Morning Herald and the Melbourne Age, among other leading newspapers in Australia). You can find the make-up of the panel and the forecast tables at – Peter Martin’s site – (he is the national economics correspondent for Fairfax).

At Peter’s site you will read that:

The BusinessDay economic survey uniquely incorporates the views of financial markets economists, academic economists and two working in industry groups – the Australian Industry Group and the Australian Workers Union.

Anyway, other than the variability in the forecasts, which is of interest in itself (I am fairly pessimistic given the current course of government policy), the fact is that I think these exercises are useful. They force a person to put their views on the public record and then stand ready to explain why things didn’t turn out the way they thought.

There were a number of articles published on Saturday associated with the survey results. One focused on the issue of the government budget – Forecasters divided on health benefits of a balanced budget – which is where you might expect ideological/model basis differences of opinion to be apparent.

I was “one of two economists to forecast the largest deficit in the survey – $20 billion (projections ranged up to a $1.5 billion surplus)” but that is because I am the most pessimistic about growth prospects in the coming year – both for Australia and the US and Chinese economies.

The article quoted me correctly as saying that I “was concerned about the large pool of under-used labour that had grown alongside the mining investment boom, and that the private domestic sector was still trying to reduce the burden of the debt build-up that accompanied the credit binge before the global financial crisis”.

I also said that at present the deficit should be around 3 per cent to 4 per cent of gross domestic product “for the immediate future, and then probably about 2 per cent of GDP continuously”.

They also quoted me correctly when I said:

There is no sense that the Australian economy is near full employment. The east coast economy, where most of us live, is close to recession …

Anyway, the other articles that were published in relation to the Survey are:

- Solid year for dollar, mixed for shares

- Raise the GST, expert panel urges

- Forecasters divided on surplus benefits

- A Keen eye for the global economy

We will see where things are at the end of the year!

Anyway, the point is that I am not against organisations producing forecasts and providing analysis for their errors. There is some problem when powerful organisations, at the centre of the economic policy making consistently make errors and millions of people lose their jobs as a consequence. The standards required in those situations for being sure that the predictions are on firm theoretical ground increase rapidly.

I have traversed the problem of poor IMF forecasting in the past. For example – Governments that deliberately undermine their economies.

So forecast errors are a fact of life. But the IMF and other major neo-liberal inspired organisations produce systematic errors – which mean they do not arise from the stochastic nature of the underlying forecasting process.

It is easy to trace these systematic mistakes to the underlying ideological biases, which shape the way they create their economic models. I was involved at one time with some work which attempted to refute some major predictions from an influential Australian model relating to employment effects of real wage cuts. The model was influential in wage setting tribunals and federal and state government approaches to wages policy.

The answers that were always provided – real wage cuts had very large positive employment effects and negligible impacts on aggregate demand. Policy advice? Cut real wages if you want to reduce mass unemployment. This, of-course is the typical mainstream economic conclusion and is the same that was tried during the Great Depression only to find out that matters became much worse.

The model in question was what economists call a – Computable general equilibrium. They are sometimes called numerical models as opposed to econometric models, which tend to be constructed by estimating relations against actual data. The so-called elasticities in the CGE model, that “capture behavioural response” really drive the model outcomes because they reflect the a priori assumptions imposed on the model by its creator. These tend to be imposed on the structure of the model.

So if the creator thinks real wage cuts will be highly beneficial the relevant elasticities throughout the model (tracing the interdependencies across the equation structure) will be chosen (made up!) to reflect that view.

Of-course, then it becomes a matter of QED and the final simulations have really no value at all. The creator could have just provided his/her “back of the envelope” estimates, based on their prejudice.

I am not saying these models are not fun to tinker with but to hold them out to be a representation of reality is far-fetched indeed. in public policy settings they are very dangerous indeed because they are paraded as being authoritative because most people have no idea of their rather crude and ideologically-tainted origins.

As an aside, a commentator or two questioned the motivation (and usefulness) of including the development of the Classical employment theory in our Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) textbook. I am working on that exposition at present. While it might look stupid and without any evidential basis when it is laid out in sterile theoretical form – as I am doing – the fact remains that the principle insights that are drawn from that framework persist in the public policy debate today.

Many of the major arguments used against the use of budget deficits and expansionary employment creation policies are sourced from that Classical approach. For example, crowding out theories (budget deficits cause interest rates to rise which damages private investment); Ricardian equivalence/zero multipliers – come from that framework; the continuously wrong predictions that quantitative easing will generate hyperinflation (or elevated inflationary expectations, which leads to accelerated inflation), the finite nature of private saving; the money multiplier and alleged control that the central bank has on the money supply; and many more aspects of the current assault on fiscal policy activism.

So if you want to be well-educated (which is the purpose of a textbook) then you have to understand where arguments come from and appreciate that these arguments are not new. They were all rehearsed years ago and refuted by theoretical logic and factual evidence at the time. The fact they keep resurfacing is testimony to the belligerent disregard for scientific practice that the mainstream of my profession practice to the highest degree.

As I have noted before – a professor once said in a classroom I was unfortunate to be a student in – if the facts contradict the theory then the facts are wrong!

This is all relevant to the IMF and the FRBNY papers because it helps us understand why the forecasts made by economists at the time were so vastly in error.

The point is that if the underlying models (with all the in-built assumptions etc) are seriously in error, then the output that is generated from them will be, in most cases, wrong. Sometimes, because of stochastic variation the forecasts will appear to be sound but over-time, as the systematic nature of the errors are revealed, the evidence mounts. No surprise about that.

The IMF paper addresses the:

… natural question therefore is whether forecasters have underestimated fiscal multipliers, that is, the short-term effects of government spending cuts or tax hikes on economic activity.

It reflects on the revelations in the October 2012 World Economic Outlook, which I covered in this blog – Governments that deliberately undermine their economies. The WEO reflection noted that:

Under rational expectations, and assuming that forecasters used the correct model for forecasting, the coefficient on the fiscal consolidation forecast should be zero. If, on the other hand, forecasters underestimated fiscal multipliers, there should be a negative relation between fiscal consolidation forecasts and subsequent growth forecast errors. In other words, in the latter case, growth disappointments should be larger in economies that planned greater fiscal cutbacks. This is what we found.

Which in plain English says that the theoretical structure that the IMF have based their policy advice – including battering nations with structural bailout packages that have created millions of jobless citizens – are wrong.

They found the relationship that is at the core of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) – that growth will falter the most in nations with the largest fiscal withdrawals (in the context that these austerity measures are firmly pro-cyclical).

Note the terminology – “planned greater fiscal cutbacks”. For example, many people have argued that you cannot blame the fiscal austerity in the UK for the descent back into recession (which dip are we up to at present?) because the economy went backwards before the main public spending cutbacks and tax hikes were introduced.

The problem is that households and firms, already struggling with recessed labour and housing markets and unsustainable debt levels, anticipated the impact of the cutbacks and refused to lift their spending growth rates. The next year will be particularly poor in the UK once the full suite of the austerity rides rough shod over an already recessed private domestic sector outlook.

The IMF paper claims that in Europe “conditions for larger- than-normal multipliers were ripe” because “a number of large multiyear fiscal consolidation plans were announced” in early 2010.

They didn’t tell the world that at the time. They claimed it was imperative that fiscal consolidation be instituted in most advanced nations. The IMF regularly bombarded us with forecasts of how export-led recoveries were in the wind as long as nations stuck to their domestic deflation strategies (aka cut wages and benefits and government spending generally).

At the time (July 2010), I wrote this blog among others – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – which warned against the export-led dogma being pushed by the IMF, the OECD, the EU and others (including the incoming British coalition government).

I noted that the development of Keynesian macroeconomics was important because it allowed us to see the logical error lie in the way in which mainstream economics developed. The latter is still essentially ground in a microeconomic framework, starting its a priori reasoning from the perspective of an atomistic individual.

To make statements about industry or markets or the economy as a whole, the mainstream aggregate their atomistic analysis. Of-course this proves to be impossible using any reasonable basis and so they fudge the task and assume constructs like the “representative household” to be the demand side of a product market and the “representative firm” to be the supply side. Together they bought and sold a “composite good”.

The fudge comes because in this sleight of hand the principles that apply to the individual were transferred over to the composite or aggregate.

So the economy is seen as being just like a household or single firm. Accordingly, changes in behaviour or circumstances that might benefit the individual or the firm are automatically claimed to be of benefit to the economy as a whole.

The general reasoning failure that occurs when one tries to apply logic that might operate at a micro level to the macro level is called the fallacy of composition. In fact, it is what led to the establishment of macroeconomics as a separate discipline. As indicated, prior to the Great Depression, macroeconomics was thought of as an aggregation of microeconomics. The neo-classical economists (who are the precursors to the modern neo-liberals) didn’t understand the fallacy of composition trap and advocated spending cuts and wage cuts at the height of the Depression.

Keynes led the attack on the mainstream by exposing several fallacies of composition, although Karl Marx clearly understood the issue.

In the modern debate, demand for widespread fiscal austerity is the latest example of fallacy of composition in mainstream economics. I explain in more detail in the cited blog.

But the IMF has pushing export-oriented growth strategies onto developing countries for years. In the case of trade, the fallacy of composition becomes an “adding-up” constraint on the capacity of nations to simultaneously export goods to external markets – which often amounts to many nations trying to penetrate the same markets.

The IMF and now the austerity crazies invoke the usual arguments. First, there will be no demand-side constraints because the wealthier nations will grow fast enough to support the higher import volumes and avoid supply gluts depressing export prices. Second, the poorer nations will start trading between themselves. Third, poorer nations steadily introduce capital-intensive production techniques and make way for other nations to export labour intensive goods.

If you read the extensive research literature on this topic you will discover that in reality demand-constraints that arise from competition in limited export markets are binding. Further, glutted markets saw export prices continually collapsing for less developed countries who then had to borrow further from the IMF to make ends meet. In the meantime, these nations undermined their subsistence agriculture by turning it into cash crops and so people starved.

But the current austerity plans have some similarities with the flawed IMF development strategy, which is no surprise given the IMF wrote the recent G20 response endorsing the austerity programs.

In 2010 as the calls for fiscal austerity were gathering pace, people started quoting from a few economic research papers that allegedly documented cases where austerity has led to growth. Two countries were often held out as exemplars of this approach – Canada and Sweden in the 1990s.

In both cases the governments cut back their net spending and growth emerged in subsequent years.

But what they fail to add is that the rest of the world was growing strongly at the time. So while Canada may have been able to offset the public spending cuts by an improving external sector helped along by increased competitiveness via exchange rate adjustments, this solution cannot work if all countries engage in austerity. That is the fallacy of composition.

Export-led growth strategy cannot apply for all nations which are simultaneously cutting back on their domestic demand.

The only reliable way to avoid a fallacy of composition like this is to maintain adequate fiscal support from spending while the private sector reduces its excessive debt levels via saving.

That strategy is also likely to be the best one for stimulating exports because world income growth will be stronger and imports are a function of GDP growth.

So there was never a surprise that the multipliers were “larger” than the IMF predicted. The predictions were always too low and wrong. That is because the IMF uses a flawed macroeconomic approach.

The IMF paper now finds:

… a significant negative relation between fiscal consolidation forecasts made in 2010 and subsequent growth forecast errors. In the baseline specification, the estimate … [implies] … that, for every additional percentage point of GDP of fiscal consolidation, GDP was about 1 percent lower than forecast.

In more accessible language, the larger was the planned fiscal consolidation at the start of 2010, the larger the actual decline in real GDP relative to what the IMF thought it would be.

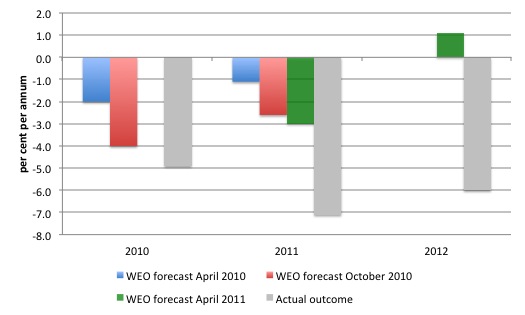

So for Greece, for example, in its – April 2010 WEO – the IMF predicted that Greece would experience a real GDP growth rate of minus 2 per cent in 2010 and -1.1 per cent in 2011.

Six months later, in the October 2010 WEO – it revised these forecasts to -4 per cent (2010) and -2.6 per cent in 2011.

By the – April 2011 WEO – we learn that the IMF thinks that the Greek economy will decline by 3 per cent in 2011 but return to a 1.1 per cent growth rate in 2012. Yes, you read that correctly.

The facts are very different (see Eurostat data.

The following graph shows the evolution of the IMFs forecasts against the reality (the missing columns relate to the moving nature of the forecast horizons).

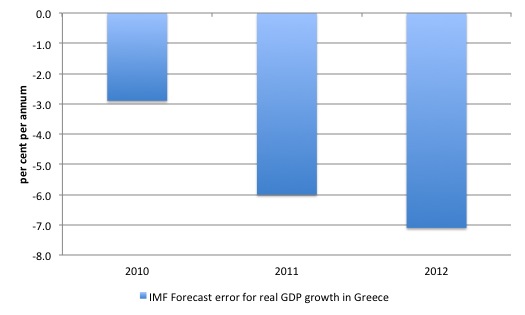

The IMF underestimated the contraction by 2.9 per cent in 2010 (based on the April 2010 predictions); by 6 per cent in 2011 (based on April 2010 predictions); and by a staggering 7.1 per cent (based on their April 2011 predictions).

The errors were systematic in direction and very large.

These errors are shown in the next graph.

What do the IMF think their results mean?

They say:

Our results suggest that actual fiscal multipliers have been larger than forecasters assumed.

They guess that the average figure used in forecasts was a multiplier of 0.5. That means that for every $1 the government spends the economy will only grow by 50 cents. Where does the other 50 cents go given that $1 of spending adds that much to national income initially?

The answer is that the models assume that there is private sector crowding out and Ricardian effects which lead to an offset of 50 cents in other production that would otherwise have occurred if the government didn’t spend the $1.

However, the evidence supports the finding “that actual multipliers were substantially above 1 early in the crisis”. That is, the $1 of extra spending would multiply to be much more than $1 (crowding in) because of induced consumption spending and favourable investment response to the initial increases in output.

This means – for policy makers – that:

it seems safe for the time being, when thinking about fiscal consolidation, to assume higher multipliers than before the crisis.

And after all that, the IMF authors – in this case Chief economist Olivier Blanchard and an offsider – cannot quite Cross the Rubicon!

They claim that as the last word:

In particular, the results do not imply that fiscal consolidation is undesirable. Virtually all advanced economies face the challenge of fiscal adjustment in response to elevated government debt levels and future pressures on public finances from demographic change. The short-term effects of fiscal policy on economic activity are only one of the many factors that need to be considered in determining the appropriate pace of fiscal consolidation for any single country.

I just love this sort of indifference. The idea that we are now construing a four or five year horizon to be the “short-term effects of fiscal policy” – given that over that time, millions of people have become unemployed, and have experienced a steady draining of their accumulated financial assets (saving etc) and are now faced with a future of zero superannuation, declining health and no income.

Tens of thousands of children have died because of these “short-term effects” – which I guess for them was actually short-term given they didn’t live very long.

The mantra of the neo-liberals lives on. No humiliation for their errors. No reflection as to why the errors occurred. What we get is a technical exercise which is of interest but hardly a mea culpa.

Sickening to the core really.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York paper is more explicit, which I guess reflects both on the integrity of the authors and the nature of the institutions they work for.

I haven’t much time to tell you about it in detail but the main thrust of the paper is to examine the impact of the “reduced the payroll taxes (social security and Medicare) withheld from workers’ paychecks from 6.2% to 4.2% for all of 2011”. These are of-course the measures that have now expired and were left out of the ridiculous “agreement” about the “fiscal cliff” reached last week.

The paper notes that mainstream economic theory – for example “the life-cycle/permanent income hypothesis” – the impact of the payroll tax cuts “should be small”. Further, the mainstream concept of “Ricardian equivalence implies no spending response, since individuals should anticipate higher future taxes to o§set the tax cut”.

Several economists came out at the time citing Ricardian equivalence. Even the UK politicians cited it when trying to justify the imposition of pro-cyclical fiscal austerity.

Please read my blog – Pushing the fantasy barrow – for more discussion on Ricardian Equivalence. The FRBNY paper provides yet further evidence – in a long trail of similar findings over the last 30 years – that this concept – central to mainstream thinking and policy notions – is a total myth.

What the paper did was to survey workers:

… at two points in time: in early-2011, around the time the tax cut was first enacted, and then in mid-December 2011, close to the expiration of the initial tax cuts. The first survey asked respondents how they intended to spend the extra funds from the payroll tax cut in their paychecks, while the second survey inquired about actual usage of the funds.

The first survey found that that only 12 per cent of respondents said they were “intending to mostly spend the funds” and that the “average intended marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is 13.7 percent”. Which means that even though the workers knew the income boost was temporary (given the sunset nature of the initiative) they planned to spend about 13.7 per cent of the boost.

The paper then says that:

However, data from the second survey reveal that many more respondents – 35 percent report – having spent most of the funds. In fact, the average actual MPC is 35.9 percent.

That is a major discrepancy but also suggests that the payroll tax cuts were stimulatory.

The FRBNY paper concluded that:

Our estimates are inconsistent with both the canonical life-cycle/permanent income theory and with Ricardian equivalence, since they would either imply a small spending response (equivalent to the annuity value of the stimulus) or no response to the extra income. Our estimated actual MPC is at the higher end of the range found in studies that examine consumer response to relatively recent tax rebates.

There is much more detail in the paper that is of interest.

One point that is often made by conservative economists is that fiscal stimulus is partly wasted because it is used to pay down debt. Indeed, the FRBNY paper found that low income recipients of the higher income did not spend “a greater proportion of the extra funds”.

They found that “high-income workers use the largest share of the tax cut funds for consumption, while low-income workers use most of them to pay down debt”.

It has always amused me when mainstream economists rail about the ineffectiveness of fiscal policy given that recipients of the stimulus use it to pay down debt. What exactly do they expect given that the crisis was caused by unsustainable levels of private debt?

It is obvious that people who are labouring under unsustainable levels of debt and a heightened risk of unemployment will do what they can to reduce the debt and allow themselves more flexibility. That is the exact adjustment that is required in this sort of “balance sheet” recession.

Please read my blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more discussion on this point.

By supporting income growth, fiscal policy stimulus provides a positive environment for the essential restructuring of private balance sheets to take place. In that sense, the fiscal support shortens the duration of the crisis and allows the private sector to resume more usual spending and saving patterns that were distorted during the asset price boom and related credit binge.

The other point is that the larger is the saving drain (paying down debt) the larger is the required fiscal stimulus to kickstart growth. That is what has been forgotten in this episode.

Shifts in deficits were considered “large” but relative to the scale of the problem were actually not very large at all. They should have been larger earlier. The response of the mainstream then to hector governments into fiscal austerity, supported by the fraudulent fiscal multipliers used by the IMF, has only prolonged the crisis and increased the real damage to catastrophic levels in some nations.

Conclusion

The depressing feature of reading this sort of literature is that there is no real recognition from the IMF that their underlying approach was at fault. They have to admit they were grossly wrong.

But then they use economist-speak to depersonalise the damage they have caused and the culpability lies elsewhere … always.

I will write a blog at the end of the year if I am still writing them and account for my forecast errors. I hope in a way they are wrong by a mile (that is, overly pessimistic). Then I will be a fool but thousands will have work that I don’t at this point expect them to have.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill,

yes the IMF basically admits the fiscal multiplier has been much higher than estimated. However (p.19)

“… our results need to be interpreted with care. As suggested by both theoretical

considerations and the evidence in this and other empirical papers, there is no single

multiplier for all times and all countries. Multipliers can be higher or lower across time and

across economies. In some cases, confidence effects may partly offset direct effects. As

economies recover, and economies exit the liquidity trap, multipliers are likely to return to

their precrisis levels. Nevertheless, it seems safe for the time being, when thinking about

fiscal consolidation, to assume higher multipliers than before the crisis.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing that deciding on the appropriate stance of fiscal policy

requires much more than an assessment regarding the size of short-term fiscal multipliers.

Thus, our results should not be construed as arguing for any specific fiscal policy stance in

any specific country. In particular, the results do not imply that fiscal consolidation is

undesirable. Virtually all advanced economies face the challenge of fiscal adjustment in

response to elevated government debt levels and future pressures on public finances from

demographic change. The short-term effects of fiscal policy on economic activity are only

one of the many factors that need to be considered in determining the appropriate pace of

fiscal consolidation for any single country.”

No reason to change track, says the IMF.

Erik,

Note how Bill is dealing with the problem of private debt and the IMF conflates the problem of government debt. No expense has been spared to bail out the 1% with QE and implicit bank guarantees. So stimulus is seen as a cure for the elite.

In the meantime the rest of us are treated to unemployment,wage cuts and big hikes in the prices of the essentials ie, food,fuel and utilities. Somehow the IMF assumes that the best way to help the private individual pay off debt is to make them poorer.

That is how ridiculous the current situation is.

Krugman in a recent NYT article, The Big Fail, contends, early on, that standard economists offered good answers but ” political leaders – and all too many economists – chose to forget or ignore what they should have known” — http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/07/opinion/krugman-the-big-fail.html. This, to me, appears to be inconsistent. Nevertheless, in the piece, he references an article he wrote in 1 July 2010 entitled Myths of Austerity where he claims that austerity measures were introduced too early and based on no evidence whatsoever. He also argues that all the examples invoked to show that austerity works can be shown to be misleading and that other factors, not likely to be relevant to present circumstances, led to the eventual recoveries if you can call them that.

The IMF is mentioned in The Big Fail but he credits the institution with being able to change its position in the light of evidence and for being less enthusiastic about austerity, while noting that the IMF contends that while it was wrong others were “wronger”. His history doesn’t jibe with mine. How much less enthusiastic? Which others, other than Osborne and certain members of the Troika? His recent comments on the IMF appear to be based primarily on a recent paper written by Olivier Blanchard and Daniel Leigh presented at the AEA conference in San Diego which has just ended (no link).

In this piece, he also states a fundamental axiom of MMT, that your spending is my income and vice versa. And that a state is not like a household, which contradict statements he has made in the past. If he has altered his macroeconomic position, he hasn’t clearly said he has.

Dear Bill,

What about a very confused lawyer as your next target?

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/jan/07/germany-not-profiting-eurozone-export-boom

Regards,

I wish there were some way of holding organizations like the IMF to account for their official publications and the outcome from their suggested actions.

You added ‘ I will write a blog at the end of the year if I am still writing them and account for my forecast errors. I hope in a way they are wrong by a mile (that is, overly pessimistic)’. I hope you are still writing them, as I try to read them each morning, their surprisingly addictive

Bill, your dig at CGE modelling was well off the mark. These models can be implemented to reflect ANY a priori assumptions that you wish – including those of MMT. In fact you could use such a model to figure out if MMT is in fact internally consisent (you should try it some day). The best modellers always make explicit to the audience what they are assuming (be it a neo-classical or post-Keynesian closure of the model). That way the audience is aware of the bias in play. In Australia, we have the best CGE modellers in the world.

The second point I would like to make relates to the ‘back of the envelope’ comment you made. There are occasions where you would be unlikely to think of the back of the envelope model without having seen the results of the full model. Furthermore, a back of the envelope model is an excellent way to check the full-blown model is running correctly.

Finally, the equations in a CGE model are a great way of ensuring that you have a consistent argument, because your interpretation of the results must be explained entirely from the model, rather than some handwaiving exercise. You are forced to be consistent thoughout your explanation and can’t change your mind half way through. You also can’t rely on bits of theory that isn’t in the model just because it sounds plausible and happens to support your view. The latter is a trap that far too many ‘essay-writing’ economists fall into.

Bill, I am not saying that you’re one of them but I am saying you seem judge CGE in a rather harsh way, ironically, using the very bias you claim to be its key shortcoming.

Happy new year (and I’d still vote for you if ran for the Senate, along with Julian Assange).

Bill,

Opponents of MMT and general Keynesian counter-cyclical budgets always bleat on about two things, namely inflation-hyperinflation and stagflation. I can find your hyperinflation posts but not any posts specifically about stagflation. Even some New Keynesian economists seem to concede that the stagflation edisodes of the 1970s and 1980s pose a problem for Keynesian economics and seem to imply that an answer has not yet been sufficently elucidated. Supply shocks are often presented as a partial but incomplete (obviously) explanation for stagflation. Have you covered this?

Thanks,

Ikonoclast.

It’s another excellent essay and demonstrates once again that the empirical evidence is heavily in favour of MMT and New Keynesian economists and heavily against the Neoclassicals, Moneterists, Austrians etc.

Esp Ghia’s (good natured) dig at “essay writing economists” both does not hold water and does hold some water too. I will explain what I mean.

First, as Marx famously pointed out (and others too no doubt), mathematics is a language too. So whether you are writing in say English or German or maths you are still writing in language and if it is long-ish it is an “essay”. It is trivially simple to prove that mathematics is a language. Here goes:

(a) 1 + 1 = 2

(b) One plus one equals two.

Maths is simply a formal and precise specialist language concerned mostly with quantities and quantification. Individual “words”, symbols or operators have precise meanings which are often related by axiomatic rules.

Mathematical models are complex, interelated systems which follow or allow a flow or many flows of computational logic and use mathematical rules, conventions, constants, variables, parameters, algorithms (lists of precise instructions for performing operations) and heuristics (rules of thumb or approximation for performing operations). Mathematical models and academic essays in formal disciplines (if both are well written) both follow a flow of computational/decuctive logic that is supportable, repeatable and checkable (for want of better words, I am writing quickly).

On the other hand, reducing a wordy theory, model or prescription in a language like English to a mathematical model in the formal, precise language of mathematics and computable algorithms is as Esp Ghia said a valuable, important and indeed at times crucial exercise. I can give an example from work I was not directly involved in but which I saw second-hand and had to work closely with the outcomes (and non-outcomes) of. At one stage, the Dept. of Social Security as it was then called, conducted work attempting to reduce or render the entire Social Security Act to a computerised rules base (for the purposes of further pensions and benefits automation). It was an heroic if rather “courageous” effort in the “Yes, Minister” sense.

One key outcome, which sticks in my mind, was the discovery of several (I forget the precise number) logical inconsistences in the (very wordy and extensive) DSS legislation written of course in legalese. In other words, in these cases if one piece of the legislation was considered legal, correct and applicable, following it put one in direct conflict with the law and rule encapsulated in another piece of the legislation. I think from memory this particular heroic project eventually failed in terms of its own goals (at least in its first iteration) but I always felt a lot of useful learning, experience, other practical applications and pointers to new directions came out of it. So this experience supports Esp Ghia’s case.

However, model makers must always be aware of the model’s relation to reality (where it is attempting to model some aspect of reality) and not get lost in an idealised exercise disconnected from any validation conducted by the checking the model outputs with empirical data from the real system.

@Ikonoclast,

I actually have not read anything comprehensive by Dr. Mitchell on the subject of stagflation.

Warren Mosler has publicly stated he believes monetary policy exacerbated the problem. By raising rates the Fed pumped money into savers hands and spurred demand-pull inflation while oil costs were generating cost-push. In his words the Fed was stepping on the gas when they thought they were stepping on the brakes. I don’t have the link but he spelled this out in the second presentation on Modern Money & Public Purpose. You can find it on YouTube.

Models are excellent to reach the wrong conclusions. When changing one number in a model, it has a non-linear impact on all other numbers what makes the whole exercise questionable (due to uncountable reflexibility). This is especially true when we change from an ever increasing debt levels to an period when it slowly is recognized that the prior unsound monetary policies have produced so many distortions and mal-investments in the economy that there are no more easy solutions to the problem.

Obviously, I do see the problem from another angle than many of those who think that an economy can be manipulated to achieve a desired result. It may be possible for many years to do that but the revenge will come one day and will be much more disastrous as longer the prior period of manipulation lasted. There simply is no free lunch in the long run.

As to the present problem of too high credit levels, the decision makers upto now follow the exact wrong path by adding to the unsustainable mountains. The only real solution is in first recognizing the problem for what it is and implement a combination of the following measures:

1. Write offs

2. Increase base money in a way that benefits the general population (not the banks and elites)

3. Set strict policies with regard to credit creation by banks

4. Implement sustainable financial policies in countries

Of course, it will not be painless, but as sooner we start as sooner we shall return to new sustainable growth. All members of society have to be share in the temporary pain that will reduce the presently perceived level of wealth. As such a path would reduce the financial sector’s ability to extract an extraordinary share of wealth creation, it will be hard to sell this idea to the decision makers who are heavily influenced by exactly those interests.

Regarding the stagflation of the 70s, (I’m thinking out loud here) if the rapid rise of oil prices was at the core of this, perhaps it illustrates there is no easy financial answer to a real resource limit no matter what money system you are using.

About all that can be done is direct spending towards development of substitutes etc. In which case I think MMT or Keynesian policies are still better than neo-classical, as the neo-classicists would throw up their hands in despair believing we’ve run out of money as well as oil, and delay any attempts at finding alternatives.

What that shows is that price doesn’t get rid of the excess demand despite all the theories. It goes into a spiral.

You have to use the WWII approach to a shortage of real supply – rationing.

There’s a post on supply side (cost?) inflation here; https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=13035

Warren Mosler and Rodger Malcolm Mitchell posit that much inflation currently is petro/carbon energy caused.