I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The current and former Treasury boss speak

I was going to write about military expenditure today in the light of large cuts to defense spending that the Australian government made in last week’s Budget and the decision by the Obama Administration to make it easier for American firms to export military equipment (to who knows where!). The concept of the military-industrial complex is interesting and, to some extent, the issues that are being raised by the US decision were discussed during the Great Depression (I have been reading a lot of material from the 1930s lately). While some might (from a micro perspective) conclude that reducing spending on the military is a good thing (less violence etc) they also have to be mindful of the macro perspective which considers a $ spend on a tank to be equivalent in its impact on aggregate demand as a $ spent on public education – well nearly. But I will write about that tomorrow. There were two interesting interventions into the public debate in Australia yesterday from the current Treasury boss and the recently departed Treasury boss which have general application everywhere. While they are current I thought I would consider these general points today.

The Head of the Australian Treasury, Martin Parkinson delivered his traditional Annual post-Budget Address to the Australian Business Economists – Macroeconomic Policy for Changing Circumstances – in Sydney yesterday. You can download the Speech – should you prefer to read it off-line.

He outlined where the Treasury forecasts made in the 2011-12 Budget had failed to materialise (mostly excessive optimism regarding export growth – predicted 6.5 per cent against probably actual of 4 per cent – taking 1 per cent of total real GDP growth one you take into account the fact that imports will probably be higher than expected).

In relation to the planned fiscal austerity that the Government announced (to get the budget back into surplus despite a slowing economy), he said:

… let me make some general comments about the impact of discretionary fiscal policy on the macro-economy.

I have to admit that I am intrigued by the arguments put forward by a number of commentators on this issue. Obviously, it is not a new issue, with people arguing strenuously in recent years that the fiscal stimulus injected during the GFC had no impact on economic activity. For consistency, those same people presumably argue that that any fiscal consolidation must also have no impact on the macro-economy … [after some theoretical discussion and consideration of evidence he concluded] … In short, the standard Mundell-Fleming theory appears to hold under a specific set of conditions, but when these conditions are relaxed discretionary fiscal policy has significant real effects, and to suggest otherwise risks a triumph of ideology over experience.

So the Australian Treasury clearly thinks that the fiscal multipliers are “positive and sizeable” which runs in contradistinction to what a large number of the academic economists think. But then the latter are ruled almost entirely by ideology and refuse to adjust their position when the facts dictate otherwise.

In that context, the Treasury boss acknowledged that his Department was consistent in its view and thus knew that last week’s Budget will have “a contractionary effect on activity”. The question is how much of an effect.

Last week, the Government announced one of the largest single-year fiscal shifts in our history which amounts to 3.1 per cent of GDP in 2012-13. The Treasury boss correctly noted that the final impact (via the multipliers) depends on various factors including the (avoided) leakage from the domestic spending system (via imports).

In his analysis of the size of the real GDP contraction that the budget austerity will cause he repeated the Government’s mantra that the economy was close to full employment and growing around trend and concluded from that:

There are also those who argue that returning the budget to surplus in 2012-13 is a political gesture and there would be no great harm in delaying this by a year or so.

The problem with this argument is that if it’s not appropriate to restore the structural budget position when we have low unemployment and the economy is expected to grow at around trend, when will it be appropriate?

My first observation is that there is no necessity for the budget to be in surplus if the economy was growing on trend. Depending on the behaviour of the external sector and the private domestic sector, the structural budget position at “trend growth” could be a surplus or deficit (of varying magnitudes) or even a balance.

So for a nation with a current account deficit of say 2 per cent of GDP, and the private domestic sector spending exactly what it earns (S = I) and therefore not building indebtedness overall, the appropriate government balance would be a deficit of 2 per cent even if trend growth was being achieved.

In other words, the a particular budget balance should not be the target of policy because it is determined by both government spending and tax plans and the strength of private spending. The latter determines how much tax revenue the government earns for a given tax structure. There is nothing sacrosanct about a budget surplus in isolation from what is happening in non-government sector.

The Budget estimates for 2012-13 – which take into account the dramatic fiscal shift are interesting.

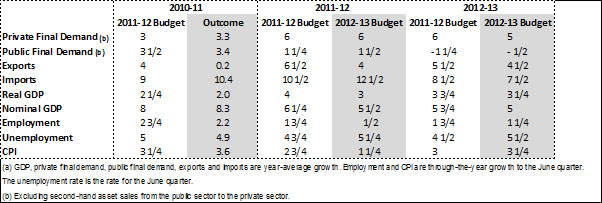

The following Table is taken from the Budget papers and shows the Treasury estimates for the next financial year and some back-casting. Note that the 2011-12 figures (for the 2012-13 Budget) are estimates made in last week’s Budget of what this year will be – when it is finished on June 30, 2012. The far right column tells you what the Treasury thinks is going to happen in the forthcoming 2012-13 financial year.

We thus know that they are forecasting exports to grow by 4.5 per cent and imports to grow by 7.5 per cent. Once you consider the secondary income transfers that are added to the trade balance to generate the Current Account – they are always negative and large – then it is clear that the Treasury is assuming a significant drain on real GDP growth coming from the external sector, mining boom (and record terms of trade for our primary commodities) notwithstanding.

From Budget Paper No. 1 .which presents the main Economic Outlook (Statement 2) we learn that:

The current account deficit is expected to widen to 4¾ per cent of GDP in 2012-13 and 6 per cent of GDP in 2013-14. This largely reflects the forecast shift of the trade balance from surplus in 2011-12 to deficit in both 2012-13 and 2013-14 because of a strong rise in resources investment-related imports and the expected decline in the terms of trade.

That is a significant aggregate demand drain from the economy and will have to offset by growth in private spending given that public spending will also be a fiscal drag on growth.

The Treasury believe that the strong growth in imports “predominantly reflects the larger-than-expected business investment growth … resources investment is very import intensive, and the shift towards investment for LNG projects makes it even more so”.

From Budget Paper No. 1 .which presents the main Economic Outlook (Statement 2) we learn that “Household consumption is expected to grow 3 per cent in both 2012-13 and 2013-14” and “New business investment growth is expected to be a strong 12½ per cent in 2012-13”.

Overall, given their relative weights in total private final demand growth is expected to be 5 per cent in 2012-13.

The Budget also estimates Private Final Demand to grow at 5 per cent about slightly slower than at present. Public Final Demand is forecast to grow at -0.5 per cent in 2012-13 down from 11.5 per cent (estimated) for this financial year.

So if you you start thinking about that from a sectoral balances perspective the arithmetic is curious (not that the information above is in sectoral balance form).

But we can do some inference drawing on other information.

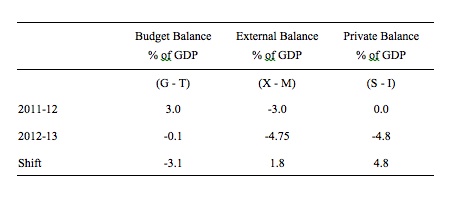

In 2011-12, the Treasury believe that the current account deficit will be 3 per cent of GDP and the budget deficit will be 3.0 per cent of GDP. For 2012-13, they are projecting a budget surplus of 0.1 per cent of GDP in 2012-13 and a current account deficit of 4.75 per cent of GDP.

We can infer what the estimate of the private domestic balance is (relationship between private spending aind income) from the sectoral balances view of the national accounts:

Private domestic balance (S – I) = Government balance (G – T) + Net Exports (X – M)

where S = total household saving, I is business investment, G is government spending, T is government tax revenue, X is exports and M is imports.

The following Table captures the implied sectoral balances for 2011-12 and 2012-13 – inferring the private domestic balance from the other two pieces of information (which is how it is generally done given the difficulty in estimating total private savings).

While it is difficult to be exact in this regard (given the data presented is not presented in a way that is conducive to computing sectoral balances) we know from the expenditure side of the National Accounts (last published for the December 2011 quarter), that the Private Gross fixed capital formation ratio (per cent to GDP) averaged 21.4 per cent in calendar year 2011.

The Household saving ratio (from disposable income) averaged 9.7 per cent (and so if we computed that ratio out of GDP it would be lower).

Given that knowledge, it is hard to believe that the private domestic balance this current financial year will come out zero. That would infer a much larger contribution to real GDP from the public sector given the behaviour of net exports.

Further the implied shift in private behaviour as the current account grows and the budget retreats (by 3.1 per cent of GDP) is dramatic and relies on massive investment growth, which I do not think will occur.

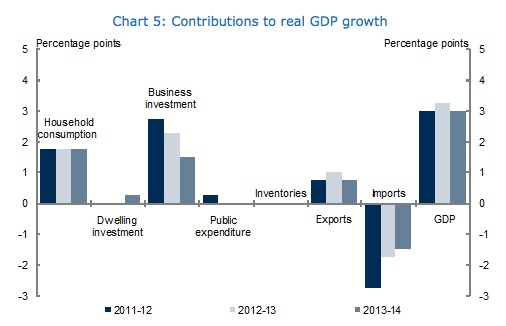

Then you look at Figure 5 from Budget Paper No. 1, which shows the estimated contributions to real GDP growth for 2011-12, 2012‑13 and 2013‑14. Household consumption is estimated to maintain a constant contribution of about 1.8 percentage points each year. Business investment is estimated to add about 2.25 percentage points to next year’s real GDP growth, while net exports will be firmly negative. Curiously, the government sector is estimated to make a near zero contribution to growth despite the Treasury admitting that the fiscal shift will reduce growth. That doesn’t add up.

But summing the contributions of household consumption and business investment in 2012-13, we get about 4 per cent real GDP growth. The overall Treasury estimate for real GDP growth is 3.25 per cent for 2012-13, which means the negative contributions from net exports and government must be estimated to be around 0.75 percentage points.

Given the current account deficit is estimated to be of the order of 4.75 per cent of GDP – the arithmetic is rather curious.

My second observation is that trend growth might not be the optimal benchmark if the economy has been operating at levels of activity for many years, which are patently well below full employment. Over the last three decades, government policy has deliberately maintained a state of the entrenched labour underutilisation.

So using the trend rate of growth associated with this historical period as the policy goal is to adopt a somewhat diminished aspiration and deliberately waste the potential of a certain proportion of the willing and available labour force.

My third observation is one I continually try to keep alive in the national debate in my media appearances. While the Treasurer and his paid officials (like the Treasury boss) maintain the mantra that the economy has recovered to trend growth and the Treasury clearly chooses to support that lie in the official Budget papers, the fact is that the Australian economy is nowhere near trend growth.

The ABS broad labour underutilisation rate is at 12.5 per cent at present, thousands are leaving the workforce for lack of opportunity, 38 odd percent of our teenagers who want to work are idle and inflation is falling significantly.

This level of labour wastage cannot be consistent with the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) – even if that concept had any policy relevance.

I can identify hundreds of thousands of jobs that would fill unmet community and environmental need in Australia at present, which would be suitable for even the most unskilled workers to be offered. The problem is that government refuses to assume its ultimate responsibility as the currency-issuer for full employment.

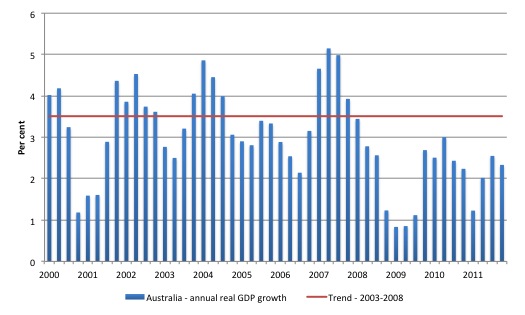

A casual examination of recent real GDP growth also supports my viewpoint that the economy is no where near trend..

The following graph is taken from ABS National Accounts data (latest available December quarter 2011) and shows the annual rate of real GDP growth since the March quarter 2000 to the December quarter 2011 (blue bars). The red line is the average growth rate (3.5 per cent) for the 20-quarters before the recent crisis impacted (September 2003 to September 2007). This is normally considered to be trend growth.

The Australian economy started slowing in the March 2008 quarter and has not gone close to achieving the growth rate that was enjoyed in the 5 year period before the crisis. The pace of growth was gathering on the back of the fiscal stimulus in the December 2009 to June 2010 quarters but then fell away as the fiscal stimulus was withdrawn.

Private domestic spending growth remains subdued and the pursuit of the fiscal surplus is now introducing serious drag on the growth rate.

The economy is nowhere near is past trend. The Treasury has a current trend estimate of 3.25 per cent which is about the average growth of the period from March quarter 2000. Even with this more subdued growth trend forecast (a period which included two major downturns as you can see from the graph), the Australian economy is nowhere near trend performance and is now moving away from that benchmark.

Please read my blog – The myths that abound in Federal Budget Papers – for more discussion on this point.

But the interesting part of the Speech was the Section entitled “Could fiscal consolidation take too much out of the economy?”, which was in reference to the various statements by commentators in the past week, including myself, that the fiscal retreat was not only unnecessary given the subdued nature of private spending.

He said that:

The impact of fiscal consolidation on economic activity, whether discretionary changes or through the operation of the automatic stabilisers, is much more nuanced than implied by simply looking at the magnitude of the fiscal consolidation – around 3.1 per cent of GDP in 2012-13.

He noted that the “economic impact of fiscal consolidation” was also influenced by the composition of the final spending and taxation – and specifically said that “a decision to reduce outlays in total but also to redistribute them in favour of those with high marginal propensities to consume would be less contractionary, and perhaps even stimulatory, than an across-the-board cut”.

This is in reference to the supposed “Robin Hood” Budget which saw some cash and other benefits to lower and middle-income earners being provided while the top-end-of-town lost some benefits.

But with the contribution to real GDP from private consumption estimated to be relatively constant over the next two budget years (see the previous graph) it is hard to see how the redistributive nature of the budget will provide significant offsets to the large cuts in the deficit.

The Melbourne Age article today (May 16, 2012) – Treasury bullish on economy – written by Peter Martin provided some more clues to the way Treasury is thinking.

The Age reports that:

In answers to questions at the annual Australian Business Economists lunch in Sydney, Dr Parkinson said taking the budget from a $44.4 billion deficit to a $1.5 billion surplus amounted to a fiscal contraction of 3.1 per cent of GDP.

But much of the money saved would not have been spent in Australia anyway. It would have gone overseas on defence equipment and foreign aid. And other decisions in the budget moved spending and concessions from people not likely to spend, to people keener to consume.

I note that the Government is achieving austerity, in part, my imposing austerity on some of the poorest nations in our region through the withdrawal of a significant volume of foreign aid. I found that part of the Budget particularly obnoxious. The Government alleges it is the party to look after the “battler”. Hypocrites!

This information though tells us that the drain on growth from the external balance would have been much larger than it already is forecast to be. This should ne understood in relation to the constant claims that we are living through a one-in-a-hundred years mining boom. What most people don’t understand is that the exports themselves are not driving growth. It is the investment spending that the Government is banking on to drive growth although by their own admissions a significant volume of that spending is associated with imports.

The cuts in defence spending were going to be the main motivation for today’s blog given that I have been reading about the Nye Committee which delivered a very damning report in 1934 on military spending in the US. But that will wait for tomorrow.

The Age article then quoted the Treasury boss:

We haven’t modelled this formally, so there’s no point looking for it under freedom of information … But the macroeconomic effect of the fiscal contraction is probably less than a per cent of GDP. That’s a ballpark figure – 1 per cent of GDP. The fiscal consolidation is 3.1 per cent of GDP, the economic contraction is 1 per cent. This does not mean the fiscal consolidation is not real. The outlays to GDP share will step below 24 per cent and stay there for the next four years. It will be the longest period of outlays below 24 per cent since the late 1970s and early 1980s.

I found the comment that they hadn’t modelled the leakages to domestic demand formally quite surprising. So the entire fiscal contraction is being done on the “back of an envelope” and they have a ballpark figure.

Further, try tallying the “the economic contraction is 1 per cent” as a result of the budget contraction (that is, the government impact on real GDP) with the earlier data I presented about contributions to growth. The estimates of the current account drain and the fiscal drain on real GDP Growth implied by all of this are not consistent with the other estimates.

My view is that when they are also acknowledging in the forward estimates that the unemployment rate will rise over the next year as a result of the contraction and there is a very real risk that their growth estimates will be overly optimistic (meaning more unemployment), that the salaries of the Treasury boss and his management should also be “ballpark figures” and be tied to the forecast error. I predict they would take severe wage cuts over the next year should that be the case.

Former Treasury Boss talks about the Eurozone

The most recently departed Treasury head, Ken Henry was interviewed on the ABC 7.30 Report last night (May 15, 2012) – Former Treasury Head slams Euro and sees Aussie boon.

He spoke of the thinking that led to the 2008 and 2009 fiscal stimulus packages (while he was still in charge) and he said that he told the Government:

… that there was no point in going in soft. If you were going to use fiscal policy to avoid a recession, you should throw a lot at it. Secondly, that although there is a temptation to think that it would be highly desirable to having something concrete, maybe even literally concrete to show for your fiscal stimulus long after the period of crisis has past, an infrastructure project for example, that is almost impossible to roll that out in a timely fashion, to roll out sufficiently to avoid a recession. So, the advice was the best thing you can do in the time available is to provide cash to households. And then the third bit of the advice was, if you think you need to do it, the quicker you do it the better, don’t wait. Don’t wait until you see the whites of the eyes. Do it. Do it early.

This is the advice that all governments should get from their Treasury departments. The former boss said he summarised his advice to government as “Go Hard, Go Early and Go to Households”.

The second stimulus package which concentrated on infrastructure was heavily criticised for being poorly planned, rorted by private contractors and construction firms and so very wasteful.

There was truth in all of that. But here the essential point about macroeconomics (which is also relevant to my discussion tomorrow about military spending), in the words of the former Treasury boss, is that:

… when you’re putting money out the door so to speak, and I know this is difficult for people to understand, it sounds counterintuitive, but actually if it’s fiscal stimulus the most important thing is to get the money out the door. But how the money is, whether the money is in some sense wasted because there’s overcharging or whatever, of course it’s an important point but from a macroeconomic perspective it’s very much second order, maybe even third order.

There is a lot in this interview but I thought his comments on the Eurozone crisis were very pertinent.

… I’ve never seen how the Euro would work, I’ve never seen how it could be expected to work without a general fiscal union. People in Australia understand that without our system of horizontal fiscal equalisation, without fiscal transfers from one state to another state, this federation would simply not hang together, there’s no way it would have hung together in the way it has without that system of fiscal transfers amongst jurisdictions. People understand that. People in Europe have not understood that and they need to understand it, the question is – whether it’s too late? That’s the question.

The interviewer (who is prone to neo-liberal thinking) then tried to claim that the Euro leaders “certainly understood it with the Maastricht treaty didn’t they? They understood they had to have some kind of fiscal union if they were going to have monetary union?”.

Which were extraordinarily ignorant questions to ask. The Stability and Growth Pact were the anathema of a properly empowered fiscal capacity at the “federal” level. The SGP was an ideological contrivance to deliberately limit the spending capacity of the member states. It provided no capacity to address asymmetric aggregate demand shocks across the regional space.

The Treasury boss replied:

… what the stability and growth pact in the Euro was designed to do was prevent governments like the Greek government from taking the easy way out and Greece did take the easy way out. So let me explain that. Here’s the issue: if you have two countries that share the same currency and they have different rates of productivity growth, the only way to make that hang together, there are two ways: one is a fiscal transfer from a high productivity growth country to a low productivity growth country. So that’s one plan, that’d be a fiscal union, if you don’t have that then the only other way to make it hang together is for the low productivity growth country to go on a fiscal expansion.

He then claim that Greece did not take the hard decisions and improve productivity growth and “that the Greek government” ran “an expansionary fiscal policy in order to try to retain something approximating full employment in this low productivity growth country” and that caused the meltdown.

Which raises the question of Spain and Ireland – they were in budget surplus leading up to the crisis?

The essential point is that a nation that surrenders its currency sovereignty and adopts a foreign currency then has to fund its deficit spending irrespective of the state of its productivity growth.

When the crisis hit the Eurozone member states, the aggregate demand collapse was so large and the reaction by the Euro leaders so poor (imposing austerity rather than supporting growth), that the bond markets were no longer prepared to fund some of the rising deficits. If the nations had their own currencies then the crisis would have remained a real one (high unemployment etc) which could have been remedied rather quickly by deprecation and domestic demand stimulus.

Instead, the flawed design of the EMU guaranteed it would become a sovereign debt crisis – that is, a test of solvency of the member states.

Conclusion

I have run out of time today. Tonight we all tune in for another edition of the Euro crisis.

In the next 12 months we will see how robust the Australian economy is. My estimate is that it won’t be as strong as the Treasury estimate and the Budget will remain in deficit courtesy of the automatic stabilisers. This time next year you will be able to tell me that I am wrong. I hope I am.

That is enough for today!

I’m old enough to have lived through a boom (in the Old Dart), and it was great: there were jobs for pretty much everyone who wanted one and a palpable feeling of good times.

My casual job is over at the end of next month and I’m very gloomy about getting anything to replace it. There is no sign of the mining fairy dust here in Brisbane. Still, I’ll be able to enjoy our lavish safety net: when I signed on last year, Newstart and rent assistance combined amounted to 20 bucks less than my rent each fortnight. Let them eat grass!

Couple of questions:

(i) What’s the standard Mundell-Fleming theory

(ii) What’s the ‘classic Hawtrey/Cassel quantity of money mechanism

(as in ‘sovereign central banks have the means to defeat any depression thrown at them by launching mass purchases of assets outside the banking system, working through the classic Hawtrey-Cassel quantity of money mechanism until nominal GDP is restored to its trend line.’ – which I saw in the UK’s Telegraph the other day).

I hate it when people try and name drop to make themselves look clever – particularly as they are well aware that their audience hasn’t a clue what they are on about.

Bill is always so meticulous in his explanations. Clearly I’ve been spoilt.

Neil,

Check out “Flawed macroeconomic models lead to erroneous conclusions” from 21/03/12

This is how much we lost by not studying eCONomics for 5 years.

Meanwhile, back in the US, Timothy Geithner was last seen attending the annual Pete Peterson stroke fest along with Paul Ryan, Paul’s now ideological Siamese twin, Bill Clinton, and the bevy of other deficit hawks that Peterson always makes sure to invite. They all decided it was all our fault, and were particularly chargrined that some of us might not entirely agree.

“What follows denial?” quipped Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner. “Anger?” [Actual quote, reported by Fox News.]

So Tiny Tim is now apparently equating the deficit with the death progression. Run out of ideas much, Timmy?

I hate it when people try and name drop to make themselves look clever – particularly as they are well aware that their audience hasn’t a clue what they are on about. You should welcome such hatred. It’s not a decisive indication – there are uses, sometimes unavoidable, for jargon. But it’s is a sign – particularly useful in economics – that fundamentally the clever name-dropper hasn’t a clue what they are on about themself – that they couldn’t spoil you as Bill does if they had a gun to their head.