I have closely followed the progress of India's - Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee…

Investing in a Job Guarantee – how much?

This is a background blog which will support the release of my Fantasy Budget 2013-14, which will be part of Crikey’s Budget coverage leading up to the delivery of the Federal Budget on May 14, 2013. This blog will provide a detailed analysis of the investment the federal government would have to make to introduce a Job Guarantee. You will see how surprisingly small that investment is.

The complete suite of Fantasy Budget blogs are as follows:

- The indecent inconsistency of the neo-liberals

- Australia output gap – not close to full capacity

- Daily macroeconomic income losses from unemployment

- The Australian labour market – 815 thousand jobs from full employment

- What is a Job Guarantee?

- Investing in a Job Guarantee – how much?

- MMT Budgetary Principles

- The Fantasy Budget 2013-14

Introduction

In previous background blogs I have estimated the output gap to be around 4 per cent or $A60 billion on an annualised basis.

In the last background blog I proposed that the first step to closing that gap should be for the federal government to introduce a Job Guarantee, an open an open-ended public employment program that offers a job at a living (minimum) wage to anyone who wants to work but cannot find employment.

The question I posed was this: Can we create enough jobs within the estimated output gap so as not to push nominal expansion beyond the real capacity of the economy to absorb it?

In this blog I will show you how that is possible.

| The total government investment in job creation required to create 594.3 thousand jobs is $A22.0 billion (net) over a full year, This would bring the official unemployment rate down to 2 per cent of the available labour force and eliminate hidden unemployment. It would be a transformative investment in the well-being and productivity of the nation. |

The Centre of Full Employment and Equity (known as CofFEE) – outlined a detailed framework for assessing the required resource outlays to introduce a Job Guarantee in Australia in their 2008 Report – Creating effective local labour markets: a new framework for regional employment policy.

The modelling that I report here uses a modified version of that methodology to provide a sketch of what is involved.

In the next background blog I will outline the principles of fiscal policy for a currency-issuing government such as Australia. We will see that such a government has no financial constraints and is limited in its spending capacity by the real resources that are available for sale in its currency – that is, the available real productive space that is available to absorb the nominal expenditure without causing inflation.

So the following discussion about outlays avoids words like “costing” or “costs”. The $ figures are investments by the government in enhancing the well-being of the people.

The budget deficit-public debt debate continually reflects a misunderstanding as to what constitutes an economic cost. The numbers that appear in budget statements are not costs! The government spends by putting numbers into accounts in the banking system.

The real cost of any program is the extra real resources that the program requires for implementation. So the real cost of a Job Guarantee is the extra consumption that the formerly unemployed workers can entertain and the extra capital etc that is required to provide equipment for the workers to use in their productive pursuits.

In general, when there is persistent and high unemployment there is an abundance of real resources available which are currently unutilised or under-utilised. So in some sense, the opportunity cost of many government programs when the economy is weak is zero.

In general, government programs have to be appraised by how they use real resources rather than in terms of the nominal $-values involved.

When we ask a question like – Can the government afford this? – We are really asking whether there are sufficient real resources to underpin the program. The nominal outlay shown in the budget statement is an accounting entry and does not necessarily reflect the real resource investment.

Given the scale of labour wastage in Australia at present there is no question that the Australian government can afford such a scheme.

We also often hear statements from conservatives that a nation is “living beyond its means”. When there is an output gap of say 4 per cent and 13.9 per cent of available labour resources not being used in one way or another it is difficult to make any sense of that sort of statement.

There is a plethora of “means” available in Australia which we choose for political reasons to waste.

But with these caveats in mind and in the interests of transparency, this blog presents a thorough assessment of the nominal investments that the Federal Government would have to make to introduce a JG in Australia.

Background data gathering with respect to direct and indirect outlays.

In a three-year study, CofFEE was able to determine very detailed operational information from local governments about capital to labour ratios; the extent of additional equipment (protective clothing etc) required; standard training resource requirements; the ratio of supervisory to operational staff required; purchase and rental costs of additional equipment, outlays on standard raw materials for given job descriptors; and extra administrative and operational outlays that would be required.

In short, a massive amount of very fine-grained information was assembled on what resources would be required to mount a Job Guarantee program.

We also consulted the international literature to ascertain realistic parameters for capital and training costs and cross-matched this information with the data we gleaned from our interviews with local government officers in Australia.

From the interviews with local government finance officers, the results of the national local government JG survey, and the information derived from the literature review CofFEE researchers devised three stylised JG employment categories, differentiated by their labour intensity and wage to non-wage cost rules:

- Low capital intensity – 75/25 rule;

- Medium capital intensity – 60/40 rule; and

- High capital intensity – 50/50 rule.

For example, a 75/25 rule says that 75 per cent of total costs will be absorbed by wages with the remaining 25 being classified as “non-labour costs”. All other costs are included in non-labour costs, which take into account the wages of supervisors, administrative costs, materials used and capital depreciation.

These categories were then linked to the range of jobs that the local government officers identified would meet unmet community need in their local area and be accessible to the most unskilled workers.

From the national local government JG survey, the majority of jobs identified as being suitable for low skill workers were in the low capital intensity areas of work, although this varied across the specific need areas (transport amenity; community welfare services; public health and safety; and recreation and culture).

Some 83 per cent of the potential jobs identified in transport amenity (either infrastructure development or services) were in the high capital intensity class whereas 81.2 per cent of potential jobs identified in public health and safety were considered to be low in capital intensity.

We used this information to determine the direct and indirect outlays for each job. The detail is in the Report cited above.

How many jobs would be required?

Please see the background blog – The Australian labour market – 815 thousand jobs from full employment – for more detail.

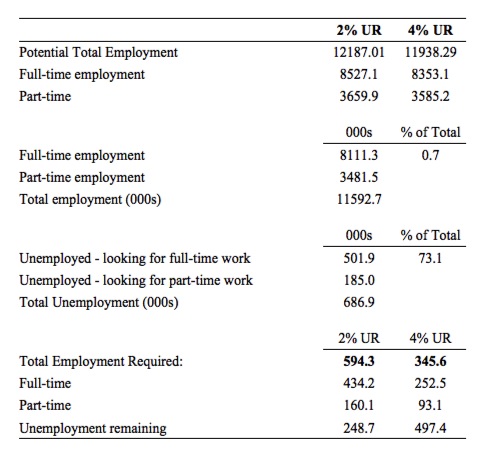

Table 1 shows the summary statistics for the labour market as at March 2013. Potential employment was estimated by adjusting the labour force for the drop in participation rate since November 2010.

The 2%UR and 4%UR columns refer to how much employment would be required to generate an unemployment rate of 2 per cent of the revised labour force and 4 per cent of the revised labour force. The current unemployment rate is 5.6 per cent and there are 150 odd thousand workers reasonably classified as being hidden unemployed.

Table 1 Determining how many Job Guarantee jobs would be required

Note that we are not aiming to reduce underemployment in this exercise. The fact is that the ABS estimated the Average weekly total cash earnings – casual – as at May 2012 were $A563.60 per week. However, the hourly wage was estimated to be $A27.80 for an average working week of 19.3 hours.

The current Federal minimum wage in Australia is $A606.40 per week or $A15.96 per hour for a 38 hour week.

We thus assume that if the Government announced this open-ended job offer at the minimum wage, very few underemployed workers would initially be attracted even though at their current wage arrangements they desire, on average, 14.3 hours of work per week extra.

It is possible that some underemployed workers would choose to moonlight in the JG to top up the hours shortfall and accept a lower wage per hour. In which case the total number of JG jobs required would be greater. We do not attempt to estimate that at this stage.

It is also possible they will some will gain jobs in the private sector as a result of the stimulus associated with the introduction of the Job Guarantee.

Further analysis and modelling is being done to determine the best way to solve the massive underemployment problem. We estimate that 305 thousand Full-Time Equivalent jobs are required to eliminate underemployment in Australia.

Gross Domestic Product and labour productivity

Nominal Gross Domestic Product for the December-quarter 2012 was $A374.4 billion. Average full-time equivalent employment was 9534.6 thousand over this period. Thus annual productivity per full-time equivalent employee was about $A157,072.

The level of foregone output associated with the prevailing level of unemployment is proxied by a direct measure of output per worker that is in turn, multiplied by the number of additional employees.

We assume that the annual productivity of the newly employed full-time equivalent workers in the private sector is 75 per cent of the average for the overall economy (that is, $117,804). The lower figure reflects the possibility that the lower skills of the unemployed and possible capital shortages resulting from the higher level of economic activity.

We assume that on-costs in the private sector are 60 per cent for all the scenarios. This is a highly conservative assumption (that is, erring on the high side).

The output of the JG workers is assumed, following National Accounting conventions that value public output at input cost, to be equal to the total cost of employing each worker (see below).

This will significantly understand the value of the employment because society, in general, and, government, in particular will save on the outlays associated with higher unemployment outside of income support – for example, reduced outlays on medical services; reduced crime rates; reduced rates of family breakdown; reduced rates of alcohol and substance abuse etc. These additional outlays are huge but are not included in our estimates.

A composite JG job was also created for the simulation reflecting the different hours worked and proportions of full-time and part-time workers in total employment. The proration of the new jobs across full-time and part-time employment also reflected the preferences of the current unemployed for full-time as opposed to part-time work.

Labour Intensity of JG Jobs

Consistent with the earlier discussion, we recognise that the type of jobs that would be suitable for the JG will have varying capital requirements.

We create a composite job in this analysis to keep it simple and adopt a 65/35 rule, which lies between the Low capital intensity 75/25 rule and the Medium capital intensity 60/40 rule and reflects the proportions that were derived from our previous research.

It is a conservative assumption erring on the high side.

Pay Arrangements

The current federal minimum award wage (delivered in March 2013) is $A606.48 per week or $A31,536.96 annually for a 38-hour working week. This is an hourly wage of $A15.96.

We assume each JG worker brings 30 per cent on-costs (including the statutory sick leave, recreation leave, long-service leave and superannuation).

In addition, consistent with the 65/35 rule adopted above, each JG job adds an additional $A22,075.87 per year in capital costs.

| The total cost of a Job Guarantee job would be $A63,074 per annum (including on-costs, and additional capital costs). |

Other Macroeconomic Assumptions including Tax Arrangements

If a JG were to be implemented, government outlays would increase through the payment of income to newly employed workers and the associated on-costs which are described above.

However, outlays would also be reduced as a result of lower unemployment benefit payments. We computed an average unemployment benefit recipient by considering the total outlays on Newstart and the number of recipients. We also assume that none of the persons who are currently classified as being out of the labour force and are discouraged workers are in receipt of Disability Support Pension. That is a simplifying assumption, which makes only a minor difference to the final results.

In addition to reducing benefit outlays, the Federal government will receive higher levels of tax receipts from three sources: (a) income tax payable by the newly employed workers; (b) increased company taxes as a result of the multiplied income gains from the initial job creation expenditure; and (c) indirect taxes as a result of the increased economic activity.

The Australian Tax Office scales for personal income tax 2012-13 were used. The corporate tax rate is set at 30 per cent.

We measure indirect taxes by noting that the ratio of GDP at factor cost to GDP at market price over the last 4 quarters was 0.8996.

As noted above, we do not take account of any of the likely reductions in government outlays, which currently are designed to address the high social costs of unemployment, notably higher crime rates and the incidence of ill-health.

We also do not take account of the administrative employment which is generated by the employment of JG workers and is reflected in the non-wage costs. We assume that the bureaucracy that currently administers the persistent unemployment becomes more productively engaged in administering the JG.

In terms of induced consumption effects, we assume that the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) of 0.8 out of changes in their disposable income, whereas profit earners are assumed to have an MPC of 0.6.

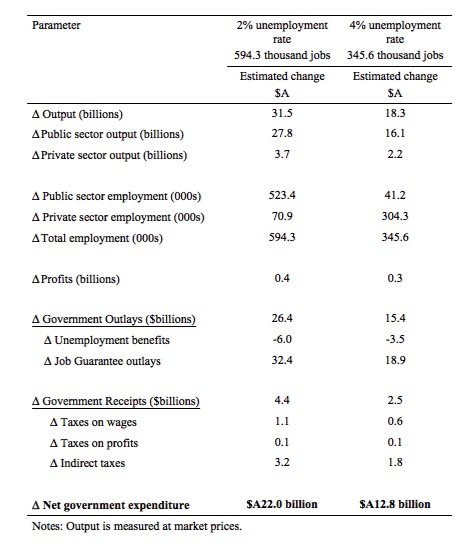

In terms of Table 1 and based on the assumptions noted above, we simulated a macroeconomic model under two scenarios. First, the government introduces a Job Guarantee sufficient to bring the unemployment rate down to 4 per cent – that is creates 345.6 thousand jobs. Second, the Job Guarantee job creation targets a 2 per cent unemployment rate – that is, creates 594.3 thousand jobs.

The results of this exercise are presented in Table 2, which is self-explanatory.

To bring down the unemployment from its present 5.6 per cent and also provide jobs for the 150 odd thousand hidden unemployed would require an investment of $A12.8 billion (net) over a full year.

Under the second scenario, an investment of $A22.0 billion (net) over a full year would be required to bring the official unemployment rate down to 2 per cent of the available labour force and eliminate hidden unemployment. That is, enjoy the benefits of increased participation.

Table 2 Government investment outlays required to introduce a Job Guarantee in 2013

The introduction of such a framework for managing variations in the economic cycle would have a transformative impact on the Australian economy and society.

It would not only create (loose) full employment and provide income security for hundreds of thousands of Australians, it would turn what has become a pernicious welfare cutting nation into a positive employed nation.

In the extended Job Guarantee literature you will read about how training and career development options are possible. The JG would replace the current emphasis on training out side the paid work environment into one that creates training slots alongside paid work, which the overwhelming weight of the research literature considers to be more effective.

Further, the JG pool would shrink very quickly once the private sector confidence returned and workers were bid out of the JG pool by higher wages and, perhaps, more attractive options.

Firms would also appreciate lower hiring and training costs because they would be hiring from already employed workers rather than hiring from a pool of unemployed. There is clear research evidence that long spells of unemployment not only undermine job skills but also lead to social dislocation.

Conclusion

What is often forgotten is that the vast majority of the unemployed (all of those on income support) are already in the public sector.

So the introduction of a Job Guarantee doesn’t alter their public sector status. It just provides them with opportunities for productive work and enhanced self-esteem. They leave welfare dependent states and become regular workers earning an income, enjoying vacations and the security of sick leave and the other protections that they miss when they are unemployed.

While I do not recommend this strategy, the Job Guarantee could be phased in over time. First, to youth. Second, to all long-term unemployed. Third, once everybody realises the sky will not fall in, to everyone who wants a job.

In terms of whether there is enough output space free to accommodate such a program – the answer is clear. The program would eliminate around 30 per cent of the existing output gap given that the JG workers are assumed, conservatively, to produce less than half per person per period than a full-time equivalent worker in the market economy.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“The total government investment in job creation required to create 594.3 jobs is $A22.0 billion (net) ”

I’m presuming there is a ‘thousand’ missing there?

What about other payments like youth allowance and parenting payments?

And these:

” If you qualify for Newstart Allowance, you may be entitled to other payments and benefits, such as:

Centrepay

Clean Energy Advance

Clean Energy Supplement

Community Development Employment Projects Supplements

Education Entry Payment

Health Care Card

Income Support Bonus

JobSearch Facilities

Jobs, Education and Training Child Care Fee Assistance

Local Connections to Work

Pensioner Concession Card

Pensioner Education Supplement

Pharmaceutical Allowance

Rent Assistance

Rent Deduction Scheme

Telephone Allowance “

Bill says, “We will see that such a government has no financial constraints and is limited in its spending capacity by the real resources..”. I completely disagree (which might sound odd coming from an MMTer). Reasons are thus.

Assuming no unconventional employment measures like JG, and assuming unemployment is above the level at which inflation kicks in in a serious way (which I’ll call the inflationary unemployment level (IUL)), then there are indeed “no financial constraints”. That is, government might as well increase its net spending, which will reduce unemployment. That will increase the number of regular or “non-JG” jobs.

But if unemployment is at IUL, then government cannot just write cheques for the permanent skilled labour, capital equipment and materials required for a JG scheme. (I’ll assume the wage of JG people is equal to unemployment benefit, so that’s kind of “paid for” anyway).

I.e. government cannot place orders with the private sector for the above capital equipment, materials, etc. The effect will be excess inflation.

However there is a very simple solution to the latter problem, and that’s to subsidise JG people into work with EXISTING public sector employers, where there is ALREADY a plentiful supply of permanent skilled labour, capital equipment, etc.

Alternatively, one could as it were “knick” capital equipment, materials, etc from the existing public sector, and give it to JG schemes. But in that case, those schemes would be doing much the same sort of work as the existing public sector. But that’s just duplication of effort.

Ralph – of course the government should use its existing facilities for its JG and not make an entire separate economy. I don’t think anybody has proposed different. Though it does bring up a good point. Minsky always said the JG should take people as they are, the work designed around them, their skills etc. Of course it should also take the rest of the economy as it is too – not spend like crazy on the stuff they need to do their work if it is too expensive. But we really aren’t running out of construction materials and equipment, for instance, and JG purchases for such would just push up demand and production, not prices.

You are confusing things here. The point of the JG is to avoid your IUL constraint as much as possible. “Government might as well increase its net spending” is NOT true. You are saying that the JG type targetted bottom-up expansion that Keynes himself favored is the same as the generalized “Keynesian” top-down expansion that foundered a bit in the 70s (though it was a hell of a lot better than the nonsense economics, policy and brainwashing that followed) A JG job IS a regular job. The kind of distinction you make between them, thinking that a JG is subsidized employment, and other employment is mystically not, is a major problem. You yourself refute the idea that a JG expansion is the same as a “Keynesian” one by noting that it is only the capital equipment & materials expenditure that would rise. Not the wages, because the JG wages are already “paid for”.

Really, worrying too much about inflation is silly. Unemployment is inflationary. Not having a JG is inflationary. The natural tendency of a peacetime capitalist economy is deflation, not inflation. It took a lot of neoliberal hard work sabotaging economies to create the inflation the Great Moderation (Great Stagnation) had.

The fear of inflation is completely unfounded of course – particularly demand inflation.

Because it has an easy cure. You bring the expansion of the economy to a halt before it arises. The more cautious you are, the earlier you bring the private expansion to a halt.

JG works exactly like the current unemployment buffer – except that they the output is engaged improving the common good.

Because everybody is always employed you have much more scope to bring private sector expansions to a halt – before you get into the silliness we’ve seen in the last expansion that have only been tolerated because the government was foolish enough to tie the fortunes of the economy to ‘business confidence’.

The implicit design of the post 1945 public sector was that it took on those who were difficult to employ elsewhere. The JG separates that function conceptually for the same reason that ‘social security’ is separated out of taxation – to ensure that it continues to exist regardless of the political team in charge.

Some Guy,

“of course the government should use its existing facilities for its JG and not make an entire separate economy. I don’t think anybody has proposed different.”

The WPA consisted of artificially set up “employers” which were in addition to or separate from existing employers, public and private. And numerous JG type schemes since that date have been of that nature. But I’m not sure whether Bill is proposing that sort of thing, or whether he proposes having JG people employed by EXISTING employers.

You claim, “But we really aren’t running out of construction materials and equipment, for instance, and JG purchases for such would just push up demand and production, not prices.”

If an economy is in the situation where extra demand does not significantly push up prices, then the economy is not at UIL, is it? I.e. in that scenario, extra employment can be created simply by boosting demand and creating extra regular or “non-JG” jobs.

Why create JG jobs when you can create extra normal or regular jobs?

I quite agree that “JG type targeted bottom-up expansion” would enable us to by-pass the UIL. I.e. if those who temporarily cannot find suitable jobs are offered to employers at a subsidised rate, I agree that aggregate employment rises: that is, the level of unemployment at which inflation kicks in will decline.

But agreeing with you on that point does not invalidate the basic point I made above, namely that government cannot run out and increase aggregate demand by placing large orders for capital equipment, materials, etc on setting up JG.

“The kind of distinction you make between them, thinking that a JG is subsidized employment, and other employment is mystically not, is a major problem.” Well strikes me that JG is indeed a subsidised form of employment in that the employer does not pay for the wage. E.g. if a JG employee is allocated to a public sector school, then those administering the JG system pay the wage, not the school. And if JG is extended to the private sector, then same thing applies: the employer does not pay for the wage.

Neil,

You claim that the “fear of inflation is unfounded” because “You bring the expansion of the economy to a halt before it arises.”

Well of course! We’re all agreed that inflation can be controlled by stopping any expansion in demand once inflation looms. My point is that having done that, you cannot then allow extra demand in the form of placing large orders for capital equipment, permanent skilled labour and materials needed to get JG schemes going. I.e. JG has to operate with the existing stock of capital equipment, etc. And that’s not too difficult: just subsidise JG people into work with existing employers.

I’m puzzled by your claim that “The implicit design of the post 1945 public sector was that it took on those who were difficult to employ elsewhere.” Public sector employees are actually more skilled than those in the private sector in the UK.

I’m interested in the micro-sustainability of this proposal, avoiding the deficit debate etc.

If personal tax were re-engineered exclusively to fund the JG (a genuine “Robin Hood” tax), with exemption below (say) Minimum Wage + 10 pc; your 2 pc scenario numbers appear to translate (annually) to a one-off levy of ~$2000 and tax of ~$400 thereafter.

These are respectively ~6 pc and ~1.2 pc of your Minimum Wage, so remarkably affordable for a complete solution.

May we have an expert appraisal (or correction) of this?

I wonder what the equivalent figures would be for the UK?

Hi Bill,

I know this is a pretty old post now but do you have this in an excel spreadsheet or otherwise including your formulas/calculations for Table 2? I’d love to be able to plug in today’s numbers for it. I can easily determine that for the financial cost of a JG job but I am not nearly as clued in as I hoped to be to calculate the formulas for Table 2.

If you can, thank you very much in advance. If not, I’ll keep trying to work it out for 2019 or 2020 figures.

Kind regards,

Senexx