Last night, the Federal Government brought down the – 2013-14 Budget – claiming it was a responsible response to the circumstances it faced (declining world growth, declining terms of trade and persistently high exchange rate) and that it emphasised growth and jobs. Neither claim is remotely correct. It is a pro-cyclical budget – that is,…

The Australian labour market – 815 thousand jobs from full employment

This is a short background blog which will support the release of my Fantasy Budget 2013-14, which will be part of Crikey’s Budget coverage leading up to the delivery of the Federal Budget on May 14, 2013. The topic of this blog is the state of the Australian labour market and is an overview of the detailed monthly reports I provide to coincide with the release of the Labour Force data by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. To review these monthly reports please see the blogs under the – Labour Force – category.

The complete suite of Fantasy Budget blogs are as follows:

- The indecent inconsistency of the neo-liberals

- Australia output gap – not close to full capacity

- Daily macroeconomic income losses from unemployment

- The Australian labour market – 815 thousand jobs from full employment

- What is a Job Guarantee?

- Investing in a Job Guarantee – how much?

- MMT Budgetary Principles

- The Fantasy Budget 2013-14

Introduction

The Australian government likes to tell us that the Australian economy is close to or at full employment. They frame their budget responses as if that was true.

The fact is that the Australian economy is a hundreds of thousands of jobs short of being at full employment and as a consequence the fiscal stance of the Government has been too biased towards austerity.

There needs to be a greater deficit to generate higher levels of activity in the economy and more employment given the current spending preferences of the non-government sector.

Here are some summary facts:

- In March 2013, there were 670,400 persons unemployed at an official unemployment rate of 5.6 per cent. This seriously understates the extent of labour wastage in the economy.

- The current participation rate is 0.8 percentage points below its recent peak in November 2010, which means that some 155,000 workers have left the workforce because of the lack of employment opportunities. These workers would quickly take jobs if they were offered.

- The ABS estimates there are 84,300 persons who want to work, are actively looking for work and are available to start work within four weeks. There are 106,000 persons who want to work and are available to start work within four weeks but who have given up actively looking because there are not enough jobs.

- In March 2013, there were 869 thousand persons underemployed. Remember to be classified as employed by the ABS a person only has to work 1 or more hours per week.

- The underemployed are workers who want more hours of work but cannot find them. On average they desire an additional 14.3 hours per person. The current underemployment rate is 7.1 per cent. To eliminate this labour wastage would require 316 thousand Full-time equivalent positions (38 hour week).

- The total estimated labour wastage in Australia – taking into account unemployment, hidden unemployment and underemployment – is currently at 13.9 per cent of the available labour force. For teenagers the equivalent figure is a stunning 39.4 per cent.

- Even to get back to where the economy was at the start of the crisis in February 2008 would require some 398 thousand jobs to be created. This would ensure the unemployment rate was 4 per cent, the underemployment rate 5.9 per cent and the participation rate at its February 2008 level.

- Even at February 2008, the broad labour underutilisation rate was close to 10 per cent, which means the economy wasn’t at full employment then.

- If we define a reasonable full employment policy goal of 2 per cent unemployment, zero hidden unemployment and zero underemployment, then the Australian labour market needs to create a further 815 odd thousand jobs.

Many economists will argue that in February 2008, inflation had been rising and so the economy was probably at over-full employment. Certainly that was a popular argument at the time and the current Government in the months leading up to the crisis was invoking the inflation bogey as a justification for tightening its fiscal stance.

The reality was different. The price pressures were mostly coming from external factors (oil price hikes) and the impacts of natural disasters in this country on food prices. There were no labour market cost pressures at that time.

In fact, if you strip the volatile items out of the CPI, inflation was benign in the period leading up to the crisis.

Monthly Labour Force Commentary

For more detailed analysis of the labour market, please see my – Monthly Labour Force Commentary.

Don’t forget history

We often forget history – when things happen and how. In the midst of on-going debates about fiscal austerity and the need for budget surpluses, labour market deregulation, minimum wages and taxation reform, the most salient, empirically robust fact that has pervaded the last three decades is that the actual GDP growth rate has rarely reached a rate of growth sufficient to provide jobs for those that desired them and were available.

Prior to 1974, the growth rate of GDP was typically sufficient to match the required growth rate set by the growth of the labour force and labour productivity in Australia. After that point, GDP growth was never sufficient and unemployment rises and falls reflected the history of that deficiency.

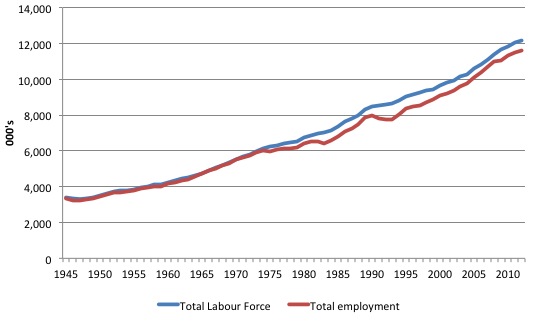

Figure 1 shows the Post World War II performance of the labour market in terms of the relationship between the labour force and total employment in 000s from 1945 to 2012.

Since 1974, the ideas of free market economists have dominated the policy debate despite being discredited during the Great Depression. The resulting policies were based on a belief that the market would generate full employment if the government reduced regulations relating to job protection and weakened the trade unions. The Australian government has complied with both agendas.

Since the change in policy stance in the mid-1970s, total employment has failed to grow in proportion to the labour force. This divergence between total employment and the labour force accounts for the rise in persistent unemployment.

| Since governments adopted neo-liberal approaches to budgets, total employment has never matched the labour force and the result is a massive waste of labour resources |

It is not that the labour force growth has been particularly erratic. The fact is that the Australian labour market has not generated enough employment in both jobs and hours of work since the mid-1970s and a major reason for that has been the restrictive budgets that the federal government has sought to run.

In the last two decades, as unemployment has fallen somewhat, a new source of labour wastage has emerged – underemployment. That trend is not captured in Figure 1 and only serves, as we will see presently, to increase the degree of labour underutilisation in Australia.

Figure 1 Labour Force and Total Employment, Australia, 1945-2012, 000s

Current employment prospects

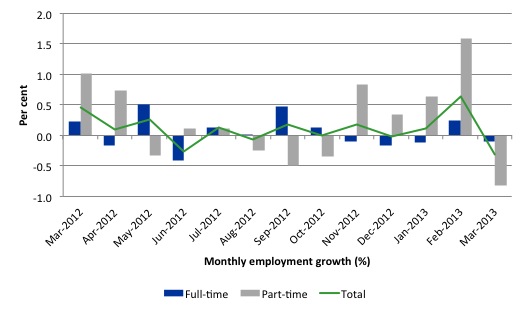

The March 2013 data showed a deterioration in the Australian labour market with negative employment growth reappearing.

Total employment decreased 36,100 (0.3 per cent) with full-time employment falling by 7,400 and part-time employment falling by a substantial 28,700.

The data reasserted the message that the labour market data has been switching back and forth regularly between negative employment growth and positive growth spikes. This monthly behaviour is producing a weak negative trend, which has been consistent for many months now.

There have been considerable fluctuations in the full-time/part-time growth over the last year with regular crossings of the zero growth line.

The following graph shows the month by month growth in full-time (blue columns), part-time (grey columns) and total employment (green line) for the 12 months to March 2013 using seasonally adjusted data.

Today’s results just repeat the topsy-turvy nature of the data over the period shown.

While full-time and part-time employment growth are fluctuating around the zero line, total employment growth is still well below the growth that was boosted by the fiscal-stimulus in the middle of 2010.

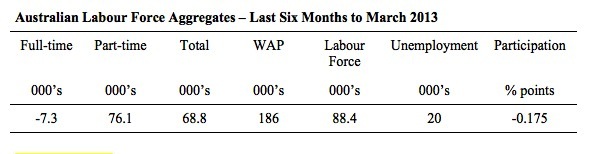

The following table provides an accounting summary of the labour market performance over the last six months. The monthly data is highly variable so this Table provides a longer view which allows for a better assessment of the trends. WAP is working age population (above 15 year olds). The first three columns show the number of jobs gained or lost (net) in the last six months.

The conclusion – overall only 68.8 thousand jobs (net) have been created in Australia over the last six months (heavily influenced by the February 2013 result). Over the last six months, full-time employment has fallen by 7.3 thousand jobs (net) while part-time work has grown by 76.1 thousand jobs (111 per cent of the total).

The Working Age Population has risen by 186 thousand in the same period while the labour force rose by 88.4 thousand. The weak employment growth has thus not been able to keep pace with the underlying population growth and unemployment has risen as a result (by 20 thousand).

The rise in unemployment has been much higher had not the participation rate fallen by 0.175 percentage points (see detailed analysis below).

This is what the Government calls near full employment

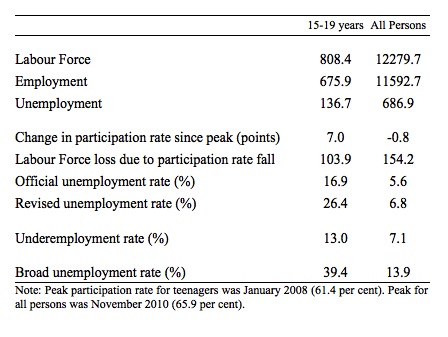

Table 1 considers the major labour market aggregates for March 2013 (seasonally adjusted) and utilises that information to calculate a broad labour underutilisation rate, which includes official unemployment, hidden unemployment and underemployment.

The proportion of the working-age population that constitutes the labour force is called the labour force participation rate. So changes in the labour force can impact on the official unemployment rate and so movements in the latter need to be interpreted carefully. A rising unemployment rate may not indicate a recessing economy nor does a falling unemployment rate indicate that things are improving.

This is because the labour force can expand (contract) as a result of general population growth (contraction) and/or increases (decreases) in the labour force participation rates.

First, as a result of poor job creation record of the economy since early 2008, participation rates have fallen sharply. The most recent peak participation rate for teenagers was in January 2008 (61.4 per cent). It is now down to 54.4 per cent a dramatic decline. We will consider the teenage labour market in more detail below.

For the aggregate, the peak participation rate was 65.9 in November 2010. In March 2013 it has fallen to 65.1 per cent – a fall of -0.8 percentage points.

These workers are being classified as not in the labour force by the ABS. There were 166.9 thousand teenagers (as at September 2012) classified by the ABS in the category “Wanted to Work, Not Actively looking for work, Available to start work within four weeks”. There were 164 thousand persons overall who wanted to work and had a close attachment to the labour force but were counted as being not in the labour force by the ABS on activity grounds.

Economists consider workers such as these, who have a close attachment to the labour force (want to and available to work but not actively seeking), to be hidden unemployed. They give up looking for jobs because there is a shortage of employment.

Table 1 shows that if we considered what the labour force would have been at the peak participation rate and then add the estimated “hidden unemployment” to the unemployed and recompute the unemployment rate we would find that the revised unemployment rate for teenagers would be 26.4 per cent rather than the official rate reported by the ABS (which does not include these participation effects) of 16.9 per cent.

For the economy as a whole the revised unemployment rate would be 6.8 per cent rather than the official rate of 5.6 per cent.

Second, the ABS considers a person to be employed if they work 1 or more hours a week. An increasing number of part-time workers are now being forced into situations because of a lack of jobs and hours on offer to work deficient hours – that is, they want to work more hours. On average, they want to work 14.3 hours extra a week (as at September 2012). The average hours worked by a casual worker is around 19 hours per week (as at May 2012).

The ABS provide estimates of the rate of underemployment which are then used to further broaden our measure of labour underutilisation. Note, the rate for teenagers is, in fact, reported by the ABS as being for 15-24 year olds. If anything, based on more detailed analysis of other data, we would expect the 15-19 rate to be a little higher.

Adding the official unemployment, the hidden unemployment and the underemployment and expressing it as a rate we get rather shocking estimates of the degree of slack in the Australian labour market.

| The broad labour underutilisation rate for teenagers is 39.4 per cent and for the economy as a whole 13.9 per cent. |

We also note that the ABS estimates that within their not in the labour force category there are 918 thousand workers who they consider to have a marginal attachment to the labour force. How many of them would seek work immediately should the economy improve is an empirical question, but our analysis here suggests at least 160 odd thousand would be looking within a few weeks.

Table 1 Summary data, Australia, March 2013

Teenagers – bearing the brunt

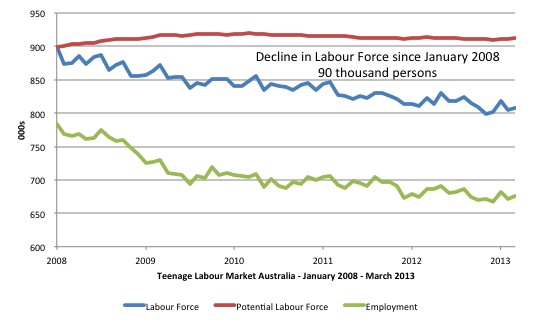

The peak participation rate for teenagers was 61.4 per cent in January 2008. That was the month before the Australian economy achieved the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle of 4 per cent (February 2008). Since that time, total employment has consistently fallen.

Between January 2008 and March 2013, the teenage labour force has shrunk by 90 thousand persons and the decline in employment has been 107.9 thousand jobs.

| Since January 2008, teenagers have lost 107.9 thousand jobs overall and 92.8 thousand full-time jobs. |

The performance of the teenage labour market over the last 12 months has been poor and should receive a much higher priority in the policy debate than it does.

The longer-run consequences of this teenage “lock out” will be very damaging.

The Australian government has no coherent strategy to resolve this appalling state. Ensuring teenagers are included in paid work, if they do not desire to remain in school, should be a number one policy priority.

The Government’s response is to push this cohort into endless training initiatives (supply-side approach) without significant benefits. The research shows overwhelmingly that job-specific skills development should be done within a paid-work environment.

I would recommend that the Australian government announce a major public sector job creation program aimed at employing, in the first instance, all the unemployed 15-19 year olds.

It is clear that the Australian labour market continues to fail our 15-19 year olds. At a time when we keep emphasising the future challenges facing the nation in terms of an ageing population and rising dependency ratios the economy still fails to provide enough work (and on-the-job experience) for our teenagers who are our future workforce.

Figure 2 Teenage labour market trends, Australia, January 2008-March 2013, 000s

Conclusion

This blog has provided only a glimpse of how poorly the Australian labour market is performing.

The economic principles that arise from this sort of analysis can be summarised as follows:

1. Mass unemployment and labour underutilisation of the magnitude described above arises because there is insufficient spending in the economy.

2. As a matter of accounting, for aggregate output to be sold, total spending must equal total income (whether actual income generated in production is fully spent or not each period). Involuntary unemployment is idle labour offered for sale with no buyers at current prices (wages).

3. Unemployment occurs when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account, but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns, other things equal. As a result, involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services translates into decreased output and employment. In this situation, nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless those cuts somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save, and thereby increase spending.

4. The purpose of government spending is to move real resources from private to public domain. The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save by the non-government sector.

5. These principles also set the limits on government spending. It is clear that government spending has to be sufficient to allow taxes to be paid. In addition, net government spending is required to meet the private desire to save (accumulate net financial assets).

6. Keynesians have used the term demand-deficient unemployment. In our conception, the basis of this deficiency is at all times inadequate net government spending, given the private spending decisions in force at any particular time.

7. The concept of fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independent of the state of the economy. We entrust government to pursue public purpose and one of the most important elements of that is to maximise employment – so that everyone has a chance to realise their potential. Once the private sector has made its spending (and saving decisions) based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those private decisions consistent with the objective of full employment.

8. Given the non-government sector overall will typically desire to net save (accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue) over the course of a business cycle this means that there will be, on average, a spending gap over the course of the same cycle that can only be filled by the national government. There is no escaping that.

9. So then the national government has a choice – maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap which means that the necessary deficit is defined by this economic goal (the zero waste goal). The budget deficit will then be whatever is required to close the spending gap. However, it is also possible that the political goals may be to maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a budget surplus will be possible.

10. However, the second option would introduce fiscal drag (deflationary forces) into the economy which will ultimately cause firms to reduce production and income and drive the budget outcome towards increasing deficits. Ultimately, the spending gap will be closed by the automatic stabilisers because falling national income ensures that that the leakages (saving, taxation and imports) equal the injections (investment, government spending and exports). That is, the sectoral balances hold (being accounting constructs). But at that point, the economy will support lower employment levels and rising unemployment. The budget will also be in deficit – but in this situation, the deficits will be what we call “bad” deficits. Bad deficits are those driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

11. Thus the concept of fiscal sustainability requires that the government fills the spending gap with “good” deficits at levels of economic activity consistent with full employment.

12. Fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independently of full employment. Once the link between full employment and the conduct of fiscal policy is abandoned, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

I have some specific questions which I hope you can address.

1. What caused the collapse of the Keynesian Consensus? More specifically, what caused the stagflation of the early 1970s? This stagflation episode seemed to be a leading cause or pretext for the monetarist, inflation-fighting, NAIRU-influenced theory of economics we have suffered for the last 40 years.

2. MMT prescriptions are considered inflationary by Monetarists and even Neo-Keynesians but why are they not concerned by the inflationary implications of uncontrolled credit, unregulated financial instruments and by asset inflation such as that in housing prices?

3. Can the current system be changed without changes in how ownership is constructed in our society? Can MMT prescriptions ever gain traction (awareness and then agreement) while the top-heavy ownership system of our society, oligarchic and corporate capitalism, holds sway? Does not this top-heavy ownership system have a vested interest in denying and obstructing MMT insights and prescriptions? Does not oligarchic capitalism deny and obstruct by its control of politics and the media? Our politicians are bought and suborned, mass or true democracy is obstructed and the media is manipulated to propagandise the populace.

Ikonoclast,

I’ll leave Bill to answer the last, but I’ll take a go at the first.

In the 70s, labour was not the limiting factor of production, oil was. Wages climbed as the middle/upper class could not decide who would have their purchasing power reduced – yet someone *must*. Exasperating things both monetary and fiscal policy was expansionary at the time (IIRC), despite that the economy could already not meet the demand for energy, the limiting factor of production.

The solution is to reduce demand on the economy such that energy is no longer limiting production through taxation (or reduced transfers/spending, higher interest rates etc), such that labour is once again the limiting factor of production. From there proceed as usual.

With a job guarantee, just increase taxes on the middle/upper class (they’re demanding more energy than the economy can support) and you’re then back to full employment and price stability.

In case the next question is what if the real factors of production don’t allow for everyone to have even a minimal income: well then, some will go without and/or starve. MMT can’t get around that, but it can certainly can solve lesser issues of stagflation.