I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

US President engaging in economic vandalism

Last week (April 5, 2013), the – US Bureau of Labor Statistics – released their latest – Employment Situation – March 2013 – which showed that in seasonally adjusted terms, total employment decreased by 206,000 in March and the labour force shrunk by a further 496,00 persons. The twin evils – falling jobs growth and declining activity. While the unemployment rate fell to 7.6 per cent (from 7.7 per cent) that is an illusory improvement. The fact is that the participation rate fell by 2 percentage points and thus hidden unemployment rose. The 290 thousand fall in official unemployment arose because the drop in employment was more than offset by the fall in the labour force. There is nothing virtuous about any of that. The facts are that it is getting harder again for Americans to get work and easier for them to lose it. The data is signalling a fairly poor outlook and hardly the time for the President to be submitting austerity budgets. But in the same week that the data came out, the President did just that. The latest budget submissions from the Administration, designed to placate the mad Republicans, is an act of economic vandalism.

The seasonally adjusted data for March 2013 showed that total employment fell by 206 thousand in the month from 143492 thousand to 143286 thousand, a decline of 0.14 per cent.

Employment growth has to absorb the growth of the labour force to ensure unemployment doesn’t rise. The task that economies typically face in a recovery from a deep recession is that the labour force growth, itself accelerates (due to the hidden or discouraged workers re-entering the labour force) and there is a huge residual pool of unemployed as to be absorbed.

Usually, employment growth is insufficient in the early stages of the recovery to absorb the unemployment quickly and so we observe the distinct cyclical asymmetry in the behaviour of unemployment over the economic cycle. It quickly rises but only falls slowly again.

In the case of the US labour market, the labour force pressure that typically slows the reduction in unemployment is not visible. In fact, as we will see below, the labour force participation rate continues to decline, which takes pressure of the employment growth. But, of-course, that is not a good sign.

While employment growth fell by 0.14 per cent, the labour force declined by 0.32 per cent, which means that unemployment fell by 290 thousand even though employment also declined.

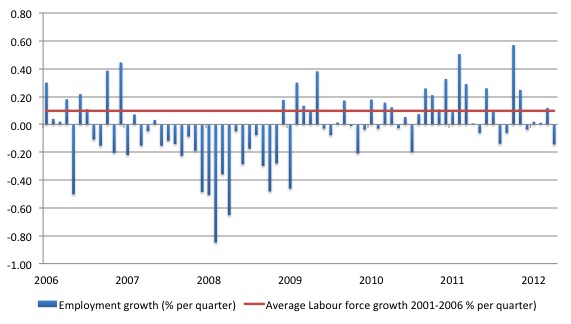

The following graph shows the monthly employment growth since the low-point unemployment rate month (December 2006). The red line is the average labour force growth over the period December 2001 to December 2006 (0.097 per cent per month). Unemployment rises if the employment growth is below the labour force growth rate.

What is apparent is that a strong positive and reinforcing trend in employment growth has not yet been established in the US labour market since the recovery began back in 2009. The labour market is limping along.

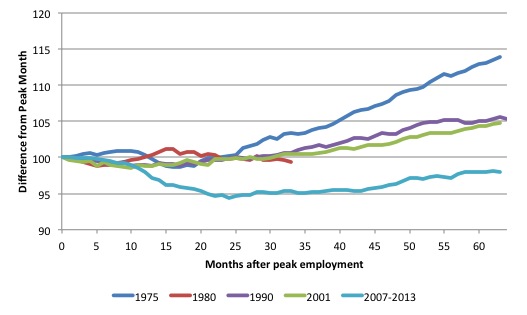

As a matter of history, the following graph shows employment indexes for the US (from US Bureau of Labor Statistics data) for the five NBER recessions since the mid-1970s.

They are indexed at the NBER peak (which doesn’t have to coincide with the employment peak). We trace them out to 64 months or so, except for the first-part of the 1980 downturn which lasted a short period.

It was followed by a second major downturn 12 months later in July 1982 which then endured. The current downturn has lasted 64 months and employment is still below the starting point of 100 (currently the index stands at 98).

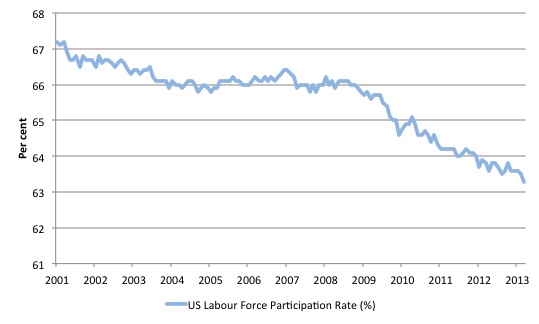

What really is striking about the last few years in the US is the falling participation rate. The following graph shows the labour force participation rate (the proportion of those above 16 years of age that are in the labour force – that is, employed or officially unemployed) since January 2001.

Clearly, there has been a trend decline in the labour force underpinning the sharp cyclical acceleration from late 2007.

Examining participation rates provides us with information about what is happening on the margin of civilian working age population and the labour force. If, for example, the participation rises, unemployment can rise even though employment growth is strong. That is a virtuous sign because it means that the economic situation is improving and discouraged workers are coming back into the labour force as the jobs market looks more hopeful.

We juxtapose that situation with one where the participation rate is falling – which suggests discouraged workers are giving up on job search because of the dearth of vacancies available and even though unemployment might actually fall, the signs are bleak. All that sort of economy is doing is trading official unemployment for hidden unemployment. The weakness just leaves the labour force.

The fall in participation since December 2006 has been stark – from 66.4 per cent to 63.3 per cent in March 2013. What does that mean in numbers?

You can compute how much larger the labour force would be if the participation rate now was at its recent (December 2006) peak by working out the current working age population and multiplying it by the peak labour participation rate.

The difference between the actual labour force now and the “potential” labour force represents the number of workers that have given up looking for work as a result of the lack of job opportunities available, upon the assumption that there have been no sharp rise in retirements.

This difference is approximately what we might call the rise in hidden unemployment and in the case of the US is equal to 7649 thousand workers.

If we added them back into the labour force and considered them to be unemployed (which is not an unreasonable assumption given that the difference between the two categories – unemployment and hidden unemployment is due to whether the person had actively searched for work in the previous month) – then the unemployment rate would rise to 11.9 per cent rather than the current official unemployment rate of 7.6 per cent.

So there is a huge degree of slack not counted among the official unemployed in the US and tells us that the unemployment rate is likely to be a very misleading indicator of how the US economy is faring.

In other words, a lot of the continuing slack is being hidden in the not in the labour force category. If employment growth speeds up then we can expect to see unemployment rise as the participation rate rises due to improving opportunities for employment. That is not happening yet as the participation rate is continuing to fall.

The UK Guardian article (April 5, 2013) – When will this do-nothing Congress wake up to America’s jobs crisis? – is one of the few that have started to pick up on the participation rate story. It has been obvious for some time that there was almost as much slack hidden outside the official unemployment numbers as there is staring us in the face in the form of unemployment.

The Guardian article said:

Nero fiddled while Rome burned; Washington politicians have apparently taken him as their inspiration.

There are fewer Americans working than at any time since 1979. This finally adds urgency – political urgency – to a jobs crisis that is only getting deeper and more painful for Americans. The numbers of jobs added and the unemployment rate don’t show the real picture of America’s employment situation. The unemployment rate keeps dropping – it’s currently at 7.6% – which gives the illusion of a better economy.

The real story is told by another number. Economists call it the “labor force participation rate”. It tells us how many people are working, and how many are dropping out of the workforce because they can’t find a single employer who could use their abilities, even for a few hours a day. The labor force participation rate is really a measure of potential that is lost: the intelligence and strength of Americans that goes idle because it cannot find a single profitable outlet.

The reference to Nero is apposite, given that Bloomberg News reported over the weekend (April 6, 2012) that – Obama Drops Stimulus for Benefit Cut to Woo Republicans.

I had only just been examining the latest US Labour Force data and concluding that things are fairly poorly over there when I read this. It almost beggars belief. The Bloomberg article said:

Less than a week after job-creation figures fell short of expectations and underscored the U.S. economy’s fragility, President Barack Obama will send Congress a budget that doesn’t include the stimulus his allies say is needed and instead embraces cuts in an appeal to Republicans.

There will be a dodge (cut) in the way social security pension are to be indexed (I will examine that in another blog) and other cuts – of the order of $1.8 trillion over the next 10 years proposed.

The Bloomberg article concludes that:

… the federal government’s fiscal policy will continue to withdraw support from the economy next year, as it has this year, possibly further sapping growth.

In his weekly audio address on April 5, 2012 – The President’s Plan to Create Jobs and Cut the Deficit – President Obama claimed that:

Our top priority as a nation, and my top priority as President, must be doing everything we can to reignite the engine of America’s growth: a rising, thriving middle class. That’s our North Star. That must drive every decision we make.

Which is a lie given the that he has sent a budget that will constrain employment growth and appears to be drafted to placate the mad Republicans.

Despite mellifluous rhetoric about “balance” and and inclusion, the President basically rehearsed the worst neo-liberal mantra there is – the fiscal contraction expansion myth:

For years, an argument in Washington has raged between reducing our deficits at all costs, and making the investments we need to grow the economy. My budget puts that argument to rest. Because we don’t have to choose between these goals – we can do both. After all, as we saw in the 1990s, nothing reduces deficits faster than a growing economy.

My budget will reduce our deficits not with aimless, reckless spending cuts that hurt students and seniors and middle-class families – but through the balanced approach that the American people prefer, and the investments that a growing economy demands.

Except that the growing economy reduces the deficit after the deficit has supported the growth in private spending to such a point that the automatic stabilisers start turning to increase tax revenue and reduce welfare spending.

That doesn’t happen if you attack the deficit first with discretionary cuts, which erode private sector spending confidence at a time when employment growth is so weak and there are so many productive workers either unemployed or hidden unemployed.

How do you respond to that lunacy? Neither senior official demonstrates that they grasp basic macroeconomics:

1. Spending equals income. If private spending is lagging then public spending has to fill the gap. Otherwise output and employment growth will be sluggish if not negative.

2. To eat into the large idle labour pool, employment growth has to be faster than labour force growth, which means that real GDP growth has to be faster than the sum of labour force and labour productivity growth.

These facts a very simple and indisputable. Cutting public spending “at this time” is the last thing the US government should be doing.

Especially when you consider the latest labour market data from the BLS.

I last calculated what economists call Transition Probabilities from the Gross Flows data for the US labour market in September 2012. To fully understand the way gross flows are assembled and the transition probabilities calculated you might like to read these blogs – What can the gross flows tell us? and More calls for job creation – but then. For earlier US analysis see this blog – Jobs are needed in the US but that would require leadership

So I started to update my US gross flows database today, which proved to be a frustrating process because the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, normally my favourite data site, has changed the way they disseminate this data. Normally offering a lot of flexibility, they are now increasingly forcing one to use java applets, which are buggy across certain computer system and so time is wasted trying to download data.

As an example, I used to be able to get a large text-file dump for the entire gross flows data. But now there is a – Data Retrieval App – to deal with – so many boxes to tick etc. Then you get a further screen with links to 51 Excel spread sheets for each column in the previous matrix of text data. The matrix used to be made available as a text file dump and it took three minutes to download, parse with scripts I had written and then ported into a spreadsheet. I cannot believe they did this. I finally worked out a way to get the text data but it took some time and it still required a fair bit of manipulation. I hope the parsing code I wrote to do this will remain relevant for sometime. BLS – please don’t change the access again for a while!

Transition probabilities are calculated from Gross labour flows data which is available from the Data Retrieval App – provided (against better judgement) by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. By way of refreshing your understanding, gross flows analysis allows us to trace flows of workers between different labour market states (employment; unemployment; and non-participation) between months. So we can see the size of the flows in and out of the labour force more easily and into the respective labour force states (employment and unemployment).

The various inflows and outflows between the labour force categories are expressed in terms of numbers of persons which can then be converted into so-called transition probabilities – the probabilities that transitions (changes of state) occur. We can then answer questions like: What is the probability that a person who is unemployed now will enter employment next period?

So if a transition probability for the shift between employment to unemployment is 0.05, we say that a worker who is currently employed has a 5 per cent chance of becoming unemployed in the next month. If this probability fell to 0.01 then we would say that the labour market is improving (only a 1 per cent chance of making this transition).

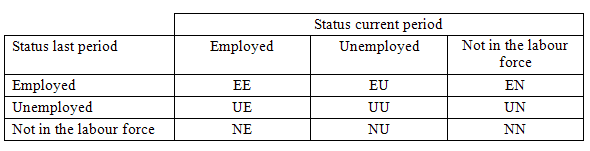

The following table shows the schematic way in which gross flows data is arranged each month – sometimes called a Gross Flows Matrix. For example, the element EE tells you how many people who were in employment in the previous month remain in employment in the current month. Similarly the element EU tells you how many people who were in employment in the previous month are now unemployed in the current month. And so on. This allows you to trace all inflows and outflows from a given state during the month in question.

The transition probabilities are computed by dividing the flow element in the matrix by the initial state. For example, if you want the probability of a worker remaining unemployed between the two months you would divide the flow (U to U) by the initial stock of unemployment. If you wanted to compute the probability that a worker would make the transition from employment to unemployment you would divide the flow (EU) by the initial stock of employment. And so on.

So for the 3 Labour Force states we can compute 9 transition probabilities reflecting the inflows and outflows from each of the combinations.

Analysing movements in these probabilities over time provides a different insight into how the labour market is performing by way of flows of workers.

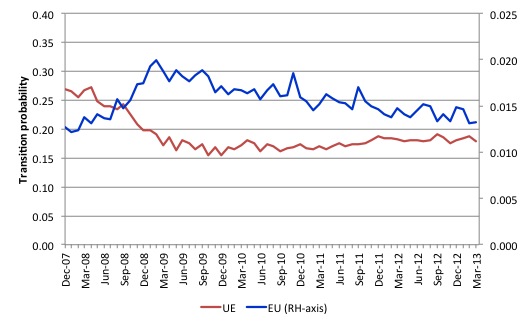

I thought this graph was interesting – it shows the transitions for EU and UE from December 2007 (when the crisis hit the US labour market) up to March 2013.

The probability of an American (in general) losing their job if employed (blue line) rose throughout 2008 (peaking at 2 per cent in February 2009), slowly evened out and is now slowly falling (1.3 per cent in March 2013).

In December 2009, the chance of an unemployed American worker gaining employment was 27 per cent. This probability fell to a low of 15.4 per cent in October 2009, and scudded along at around 17 per cent through much of 2010-2011. It peaked again in September 2012 at 19.2 per cent, but as the impacts of the fiscal retreat are starting to impact, it has fallen again and is now at 17.9 per cent.

When I see behaviour like this the only conclusion is that the recovery has stalled and America is stuck in a vicious cycle of flat private spending and confidence and an unwillingness of the US government to stimulate sufficiently to fill the gap and create work.

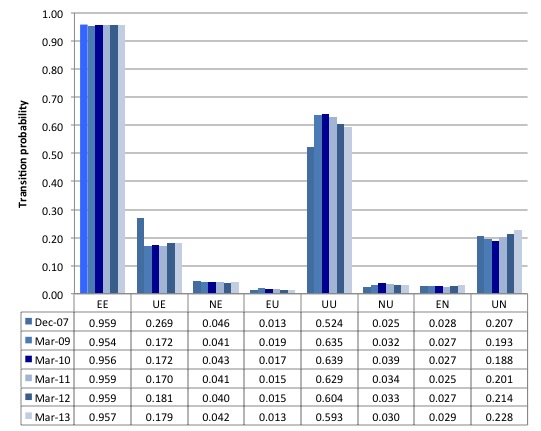

The second graph compares the US transition probabilities for various months during the crisis up until March 2013 (see the accompanying Table for values). I have also jigged the vertical and horizontal scales to allow the changes in the columns to be seen more clearly. That is one of the reasons I also provided the raw data.

Several points by way of interpretation can be made.

First, the data shows that the slight improvement in the EE probability over 2010-2012 – that is, the likelihood an employment person will remain employed in the next month (not necessarily with the same employer though) – is now reversing. So the probability of remaining employed is falling once again.

Second, in terms of the previous graph which showed that the probability of EU (employment to unemployment) is also reversing as the economy slows, the way to understand these two trends is to realise that the probability of EN is also rising after initially falling during the early stages of the recovery.

That is, workers are not as likely to retain employment now relative to earlier in 2011 but are now increasingly likely to flow out of the labour force once they lose their jobs – that is, they become hidden unemployed.

Third, the likelihood of a new entrant getting a job (NE) is fairly flat after some initial improvement in 2010. But it still remains that new entrants are more likely to become employment (NE) than enter the labour force unemployed (NU).

Fourth, the probability of an unemployed worker remaining unemployed (UU) continues to improve, although the likelihood that such a worker will leave the labour force (UN) is higher than the likelihood of them getting a job (UE) and the former probability has risen sharply over the last 12 months, which is not a good sign (and is consistent with the continued deterioration in the participation rate).

Fifth, relative to 12 months ago, employed workers are less likely to remain employed now and when they lose their jobs they are more likely to exit the labour force (EN) than become unemployed (EU).

Overall, the Gross Flows data suggests the slight improvement in the US labour market during 2012 is now evaporating.

nment policy makers should be firmly focused on maximising the potential of its population. The sustainable goal should be the zero waste of people! This at least requires the state to maximise employment – which means provide work for all those who desire work at the current wages.

It should not mean anything less than that. Policy should always be consistent with that goal.

Once the private sector has made its spending based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those private decisions consistent with the objective of full employment or else there will be national income losses and social dislocation.

Non-government spending gaps – defined as insufficient spending relative to what is required to sustain output at full employment levels – over the course of the cycle can only be filled by the government.

The national government always has a choice:

- Maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap – that is run budget deficits commensurate with non-government surpluses; OR

- Maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a budget surplus will be possible.

It is here that I always make the distinction between a “bad” versus a “good” deficit and the distinction rests on understanding the automatic stabilisers.

The automatic stabilisers ultimately close spending gaps because falling national income ensures that that the leakages equal the injections – which means that the sectoral balances hold.

But in a period of spending decline, the resulting deficits will be driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment. Fiscal sustainability is about running good deficits to achieve full employment if the circumstances require that. You cannot define fiscal sustainability independently of the real economy and what the other sectors are doing.

The automatic stabilisers make a mockery of rule-driven budget targets. Once we focus on financial ratios – deficit to GDP ratios – public debt ratios – we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end). That is why fiscal rules as stand-alone goals are meaningless or ideological.

Any financial target for budget deficits or the public debt to GDP ratio can never represent sensible policy conduct. The budget outcome is largely endogenous and thus driven by private spending decisions. It is highly unlikely that a government could actually hit some previously determined target if it wasn’t consistent with the public purpose aims to create full capacity utilisation.

In discussions of austerity there are often incompatible goals specified by proponents. The classic is their claim that austerity will allow both the private and public sector to reduce debt, when there is an external deficit. That is an impossible troika.

A national government in a fiat monetary system has specific capacities relating to the conduct of the sovereign currency. It is a monopoly issuer, which means that the government can never be revenue-constrained in a technical sense (voluntary constraints ignored). This means exactly this – it can spend whenever it wants to and has no imperative to seeks funds to facilitate the spending.

The real question is what are the limits on government spending? While a sovereign government is not financially constrained it is nonetheless constrained in real terms. It can only buy what is available for sale. Unemployment is a sign that at least one resource is available for sale.

Conclusion

The American government should go back to basics and learn these simple points. Their nation would be a lot better off if they did. They are in danger of following the UK down the slowdown-then-recession path.

In the longer-term, the US economy is in danger of destroying its middle class and further impoverishing its underclass – which I take it would destroy the “American dream”.

The numbers that appear in budget statements are not costs. The cost of a program are the extra real resources required for implementation. Persistently high unemployment means an abundance of underutilised real resources available – which means the opportunity costs are very low to non-existent.

The labour force data for March 2013 should be sending a strong signal to all US politicians that things are getting worse again.

That is enough for today!

“If private spending is lagging then public spending has to fill the gap.”

Or you try and steal some spending from some other currency area in the world (export-led growth)

Which as we’ve seen is somewhat more problematic than its proponents suggest.

Dear Bill

Is the American labor force participation rate based on the population older than 16 or on the population between 16 and 65. If the latter is the case, then part of the decline in the participation rate is due to aging. The babyboomers are reaching retirement age only this year, but life expectancy at the age of 65 is still rising, which increases the number of people over 65 but reduces the share of the population that is between 16 and 65.

Regards. James

Can’t private debts be reduced by being forgiven by the creditors rather than by being paid down using public debt expansion? If in 2008 the £10T of debt between UK financial institutions had been written down/converted to equity to recapitalize the banks, then would that not have reduced private indebtedness massively?

To my mind the huge problem with increasing government debt is that the private holders of that government debt become a constituency that needs the value of that debt to be maintained. Basically economic depression is the economic condition the best preserves the value of government debt. You create an ever more powerful constituency clamoring for that.

On the way in to work this morning I heard a BBC report that George Osborne sneaked into his Budget statement a plan to cap, what I assume to be, the ‘automatic stabilisers’…

http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2013/03/osbornes-welfare-super-cap-frightening-prospect-families

automatic stabilisers no-more.

Hi Bill

Yes, goodness knows what the President is thinking. The more he waste with his SS-cutting shenanigans the less time he spends telling the American public what the government should be doing.

Anyway, I noticed that Maggie Thatcher has kicked the stool. Will you be doing a piece in her… um… “honour”?

MMT and this posting does not deal adequately with the problem of “Anticipation”. Anticipation is the bias that all planners build into economic forecast. In the age of the Internet, knowledge is available as never before and only the least capable are bereft of historical based knowledge. History is filled with examples of inflation caused by excessive printing of money, so, based on this widely available historical knowledge, each demographic group is acting to achieve the best anticipated economic result.

What does this mean in practical terms? Obviously, retired or nearing retirement groups will reduce spending, anticipating that they will need more in retirement than they presently have. This is reinforced with lowered returns on savings, obviously orchestrated by government action. This paints an ominous future for this demographic.

Younger people nowhere near retirement are cheered by increased government spending, but, the spending is going to existing beneficiaries. The existing spending habits are easily met by present workers and machines, who also cheer the increased government spending so that they can raise prices. Of course, the increased prices only reinforce the determination of many to not spend and also lowers the ability of the lowest income to meet more than the most basic of their economic needs. This low income group includes the youngest who have never become firmly established in the work ethic. For the youth to break into the economic fabric of the economy, the task becomes increasingly difficult

If the most unstable money supply since the 1930’s has not worked to reduce unemployment, we are left with a choice between even more instability (which is what MMT suggests) or a move toward more stability. There is no question but that the retired and near retired would prefer a move toward stability. Anticipation works best when all players can anticipate a stable currency.

Over here in the US there is a persistent mantra – the mass media are “liberally” biased (liberal in the US context means “progressive”) and never give Republicans a fair hearing. I once thought that too, but now it’s obvious that what Bill refers to as “neo-liberal” (we’d call it neo-con) is actually the dominant economic mode of thinking. Though riddled with contradictions (as are pointed out in today’s blog), it appeals to the vast majority of voters who fancy themselves as purveyors of “common sense” … as in “everybody knows you can’t spend more than you take in.”

Due to that heavily ingrained belief, politicians of all stripes must cater to it by proposing to “do something about the deficit.” This is what Mr Obama (who may well understand some aspects of MMT – it might be fun to interview him on this) finds himself up against right now. Although I am not one of his bigger fans, I do believe he has a cleverness of sorts about him. He well understands that any budget proposal he makes will be less than satisfactory to the right-wing and because they have the votes to block him, it ultimately means there will be a “continuing resolution” to carry last year’s budget levels (plus an increase based on CPI) through this year. Democrats will not accept any changes in the formulae used for Social Security and Medicare/Medicaid and Republicans will block any attempts to increase taxes, so we get the status quo. This has played out now for the past four years and looks likely to continue until 2016 or so when the next presidential cycle commences.

One of my problems with Mr Obama is that he is gifted orator and could likely make serious inroads against the neo-liberal economic mainstream were he of a mind to do so. There is much material for him to draw on in this realm (perhaps Bill’s good friends Warren and Randall?). The problem, of course, will be overcoming the “common sense” mindset of the average American who likely has never studied the subject for any length of time. I believe this may be the reason the Austrians are so persuasive to many Americans, because they provide a seeming intellectual framework behind the neo-liberal mantras.

I would truly love to see some type of give and take on this subject. Currently, many Americans are terrified of the “coming apocalypse” they believe will result from uncontrolled expansion of the national debt. This has spawned a cottage industry in all manner of “survival” and “preparation” gear, marketed to them by cunning hucksters. We even see a mini-revival among some of the older folk (I am living in south Florida and encounter this mentality quite often) who sincerely believe that it is “god’s will” that our society collapse due to uncontrolled spending. The more open-minded among them take comfort in my explanations of MMT and why the deluge is not upon us, but others get quite defensive about it all. It’s as if they want to believe the worst … I cannot relate to that. As an immigrant to the US (back in 1971) I always thought of this as the “land of opportunity” and the natural sense of optimism that thinking conveyed appealed greatly to me. Where has it gone … ?

Anyway, I fully realize that continuation of the status quo will not do much to fix the growing problem with long-term unemployment. At this point, all we can hope for is a political deadlock that at least prevents the situation from growing considerably worse.

Roger,

You make a very interesting point about the “anticipation” problem. I would like to add something to that.

For anticipation problem to translate into real effects, it must be that people expect that government spending now will create future inflation, which they can then adjust for.

This is not currently the case. US inflation has not increased very much despite the massive growth in public spending since the recession. When “rational people” (the homo economicus if you will) look at the recent trends, surely they cannot anticipate much higher inflation.

The only time its rational to expect inflation is when the economy is “running hot,” ie: there is a resource constraint. With the labour market as it is now (the participation rate is falling…) and so much resource slack, surely, more spending cannot create any “rational” (in the economic sense) fear of future inflation.

What do you think?

copmcotcs

I think you are expressing the anticipations held by many people, backed up as you say with the observation that the CPI has been not increasing quickly. Others say that food has increased in price a lot, including food at restaurants. Of particular concern is the increase in fertilizer prices which seems to be following commodity prices, and portends higher food prices in the future. Despite these examples of increased prices, most would agree with you that, on the average, especially if real estate prices are included, the price of living has been fairly stable.

Anticipation tends to discount the immediate data and look more to macro events, such as the increase in U.S. federal debt. As more of a student of macroeconomics than the average joe, I can see how the money supply is increasing at fully double the rate that we have had for the last 40 years and how the increase supported a rate of inflation greater than 4% annually. That leads me to think that we should expect an inflation rate of 8% or greater at some time in the future. That anticipated rate can destroy my meager savings in a hurry.

A common shared memory held by most of the retired or nearing retired demographic is the memory of the depression as relayed by their parents. That was a horrific time for the people living through it, especially for those employed by the private sector. It is hard to dissuade these people from thinking that they need to prepare for a more economically difficult future, because it has happened in the past. (I am aware that a very large number of elderly have nearly no savings. and I have not seen recommendations about how much resources MMT might allocate to this demographic group.)

To summarize, I think that “anticipation” does not wait for inflation to happen, but incites action in anticipation of inflation.

It is hard to forecast that slowed spending can prevent inflation given that the Federal Reserve is trying to restore inflation by money supply expansion. As non-wage earners, the only choice the retired and near retired has, if they wish to adjust, is to reduce spending and make better investments.

Roger,

I can tell you are more of a student of macroeconomics than the average joe- I studied economics in college myself. What follows is a rather more detailed reflection on my thoughts. I hope you will bear with me.

Firstly, let me say that you understood the spirit of my argument perfectly when you said the following:

” Despite these examples of increased prices, most would agree with you that, on the average, especially if real estate prices are included, the price of living has been fairly stable.”

You are correct that I was talking about the expectations held by “many people” (ie the general populace). My point, largely speaking, was that inflation expectations are subdued when the economy is in a liquidity trap. Currently, I think you will agree, that the US economy is in a liquidity trap.

You wrote about the US money supply increasing by quite a factor. You are correct in that both M1 and M2 money stock have gone up quite significantly. However, this increase in the money stock has not translated into inflation simply because there has been an offsetting decrease in money velocity (in the US).

You can confirm this by going to the following graphs:

M2 money supply: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?id=M2

M2 velocity: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M2V

You can see that money velocity has declined dramatically which has offset some of the inflationary pressures that increased money supply otherwise puts on an economy. Economists like to argue that velocity is constant and therefore, an increase in the monetary base corresponds to an equal increase in inflation. This assumption is categorically false in the short and medium term (and in the long term, we’re all dead remember?).

This assumption of constant velocity was not true in the 1980s when Volcker targeted money supply growth (M1 growth). The failure of the monetarist regime in the US during the 1980s occurred precisely because the Fed, tied as it was to the growth in monetary aggregates under the monetarist regime, did not have the flexibility to adjust interest rates in the face of falling money velocity. A good amount of literature exists on the topic.

I also urge you to consider Japan. They have been trying to stimulate inflation for the better part of 2 decades now through increases in money supply. Those increases have not translated into inflation (yet, you might argue). The BOJ, as I am sure you have heard, is going for even more QE right now in an attempt to stimulate inflation. They are trying unconventional monetary policy in the wake of the failure of conventional monetary policy. They seem to have realised that the economics of a liquidity trap are quite different indeed.

The point I am trying to make still stands. There remains no reason, for anyone (be they elderly or young), to expect inflation when the economy is in a liquidity trap. The very essence of a liquidity trap is that conventional monetary policy is ineffectual at the zero lower bound (ZLB)-(ie: in increases in money supply do not spur output or inflation while an economy is in a liquidity trap) so fiscal policy is needed.

I can go into why the Fed is trying unconventional monetary policies such as “operation twist” for example. That is a discussion for another day.

copmcotcs,

What a very interesting and thoughtful post! I have read the term “liquidity trap” but never took the time to understand. I think I can see what you are saying, basing my understanding on the Wikipedia explanation.

I will try to connect some history, to see where it takes us. Of course, not all see history with the same eye.

1. The industrial economies all have high investment structures. It takes lots of expensive tools to build cars and electronics, and well trained work forces. The plants tend to be static, meaning they become tied to local structures including local government infrastructure. This makes each plant into a community necessity, resulting in community failure when the plant fails. The same structure can be extended to nations. This finally results in tremendous incentive to maintain the current economic status quo. Interest rates of zero should not deter this system.

2. In the U.S., the current ongoing recession is a recession relative to the housing bubble. The economy was producing to support the bubble with a much smaller money supply than we have now. Higher velocity of money then partly explains that fact. What is more interesting is that more people were paying for government so the observable burden of government was considerably smaller than today. While the real burden is little changed in percent of real GDP since 4 years ago, it is dramatically higher than it was just before the recession began. (I invite you to the Federal Reserve web site and create a graph of the ratio of federal expenses (FGEXPND) to GDP. This graph represents the government demand for real resources as well as charting the money supply printed or absorbed and reissued by government.)

3. While the chart above shows dramatic increase in burden of government on the private sector, the change in physical output, except for housing, is not too much changed. Few, if any, new tools nor men to operate tools have been required to support current demand.

To me, the history would agree that the economy is in a “liquidity trap”.

The challenge, then, is to justify an anticipation of future inflation and when it might begin. History and the efforts of the Fed (and now BOJ) to kindle inflation have not yet trumped the liquidity-trap-theory coupled with past BOJ experience. At the moment, the liquidity trap is holding and the future remains a puzzle.

I would have thought that the real concern with prolonged deficit spending would be more in relation to Global Trade. While obviously a monopoly issuer is not fiscally constrained, by trinity increasing money available in the economy must either increase cash rates (a blunt instrument economic handbrake) or reduce the value of the dollar. An import driven economy cannot afford to expose it’s currency to a prolonged devaluation, which means that any government expenditure needs to equate to an increase in real output, or else it is just converting $1 dollar = 1 apple into $2 = 1 apple.

The issue is where you have an automatic stabilizer such as a job guarantee, even if well executed (not competing with private sector etc), the net real economic benefit of the guarantee must be greater than the nominal costs of administering the program. Otherwise you have an ongoing situation where a government is funding a nominal GDP increase while simultaneously devaluing it’s currency in both domestic and (more importantly) international terms, for no real economic growth.