It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Keynes and the Classics Part 6

While I usually use Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray, today I am departing from that practice (deadlines looming) and devoting the next two days to textbook writing. We expect to complete the text during 2013 (to be ready in draft form for second semester teaching). Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog approach.

I am currently working on Chapter 11 which opens like this:

Chapter 11

11.1 Introduction and Aims

In Chapter 10, we discussed issues relating to labour market measurement. In this Chapter we will focus on theoretical concepts that underpin the measurement of economic activity in the labour market and the broader economy.

The Chapter has five main aims:

- To explain why mass unemployment arises and how it can be resolved.

- To develop the concept of full employment.

- To consider the relationship between unemployment and inflation – the so-called Phillips Curve.

- To develop a buffer stock framework for macroeconomic management (full employment and price stability) and compare and contrast the use of unemployment and employment as buffer stocks in this context.

- To more fully explore the concept of a Job Guarantee (employment buffer stock) approach to macroeconomic management.

NOTE:

The Keynes and Classics series so far is:

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 1 – explains how the Classical system conceived of labour supply and demand and how these come together to define the equilibrium level of the real wage and employment.

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 2 – explains how the labour market determines the level of employment and real wage, which in turn, via the production function set the real level of output.

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 3 – tied the previous conceptual development into the denial that there could be aggregate demand failures (Say’s Law), introduced the loanable funds market and discussed the pre-Keynesian critique (Marx) of the Classical full employment model.

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 4 – which began Keynes’ critique of Classical employment theory.

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 5 – continues the critique of Classical employment theory.

Today, we finish the critique by John Maynard Keynes of Say’s Law by considering his theory of interest.

NEW TEXT STARTS TODAY HERE

11.15 Keynes rejection of Say’s Law – the possibility of general overproduction

Refresher – the Loanable Funds Market

The Classical theory of interest underpins Say’s Law and the claim by Classical economists that there could not be a situation where aggregate demand was insufficient to absorb all production. The contention was that when firms choose to supply goods and services they produce output and income. That income has to be either consumed or saved.

In the Classical theory, the interest rate ensures that the income that is not consumed in each period (that is, which is saved) is also equal to aggregate investment (the creation of new productive capacity). This is the loanable funds doctrine, which we considered in Section 11.9.

Recall that the demand for loans (from firms seeking to invest in new productive capacity) was considered a decreasing function of the interest rate, the latter being the cost of borrowed funds, which would determine which investment projects were marginal and which were profitable (given expected revenue flows arising from the investment).

On the other side of the loanable funds market, saving was considered to be an increasing function of the interest rate because at higher interest rates the return on the foregone consumption (saving) would be higher and ensure higher future consumption than at lower interest rates.

The interest rate was conceived as the price of current consumption relative to future consumption. In other words, a consumer could use their income now for consumption, which necessarily meant they couldn’t use it in the future. The opportunity cost of making that decision was measured by the premium they could expect by not consuming now and loaning that income at the current interest rate. The higher the interest rate (the premium) the cheaper future consumption became relative to current consumption.

The loanable funds doctrine thus conjectured that if consumers decided to save more out of their disposable income than before, the supply of loans into the loanable funds market would increase, creating an excess supply at the current market interest rate, and market forces would start driving the interest rate down.

The falling interest rate would stimulate investment (demand for loans) and the combination of declining intention to save (as interest rates fell) and rising demand would eventually restore equilibrium in the loanable funds market (saving equals investment) at a lower interest rate.

In other words, the lost consumption spending would be replaced by increased investment spending. Real world factors like how do workers and forms easily and instantaneously shift between the production of consumption goods to the production of investment (capital) goods were assumed away.

As we will see, there is also a major issue of what market signal is provided by a decline in consumption. The implication is that the rising saving signals a desire to consume more in the future and firms re-assemble their production of capital goods to meet that demand in the future. But what consumption goods will be demanded in the future and when? These are major stumbling blocks for the Classical economists and were, in part, at the centre of Keynes’ attack on the Classical theory.

The hypothesised movements in interest rates thus ensured that there could never be an enduring excess demand or supply of loans, which then meant that aggregate demand for goods and services would always adjust to movements in aggregate supply. So full employment was ensured by the combination of real wage clearing any imblances between the demand for and the supply of labour and the interest rate moving to ensure the composition of final output supplied (between current and future goods) was always consistent with the aggregate spending (consumption and investment).

Keynes’ Critique of the Loanable Funds doctrine

Keynes was writing as he was observing what was happening in the real world during the Great Depression. It was clear that investment had fallen as had national income as economies plunged into economic crisis with rising unemployment. The flow of saving also fell in proportion with the decline in national income. While all these variables seemed related in ways that we now understand they were largely disconnected from movements in interest rates and the key predictions of loanable funds theory appeared to be without foundation.

Keynes thus considered the Classical belief that the household decision to save was determined by the preferences for current and future consumption mediated by the interest rate (the price that consumers traded current consumption for future consumption). Instead, he considered aggregate saving was a positive function of national income.

So when national output and income rises, aggregate saving will rise. The amount of extra saving per dollar of additional disposable income is called the Marginal Propensity to Save (MPC). If the MPC = 0.20, then households will save 20 cents of every extra dollar of disposable income they receive.

The interest rate might have some influence on saving but Keynes considered the influence of changes in national income to the dominant factor determining the aggregate level of savings in any period.

The other consideration is that investment spending is a component of aggregate demand, which in turn, drives total national income in each period.

Taken together, these insights undermines the concept of a loanable funds market in the way conceived by the Classical economists. There could not be independent saving and investment functions brought together by movements in the interest rate as required by the loanable funds doctrine because investment drove income which influenced saving.

In Chapter 14 The Classical Theory of the Rate of Interest – of his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, he produced a diagram to illustrate his contention that this interdependency meant the loanable funds doctrine was a “nonsense theory” (page 180).

Keynes wrote:

The independent variables of the classical theory of the rate of interest are the demand curve for capital and the influence of the rate of interest on the amount saved out of a given income; and when (e.g.) the demand curve for capital shifts, the new rate of interest, according to this theory, is given by the point of intersection between the new demand curve for capital and the curve relating the rate of interest to the amounts which will be saved out of the given income. The classical theory of the rate of interest seems to suppose that, if the demand curve for capital shifts or if the curve relating the rate of interest to the amounts saved out of a given income shifts or if both these curves shift, the new rate of interest will be given by the point of intersection of the new positions of the two curves. But this is a nonsense theory. For the assumption that income is constant is inconsistent with the assumption that these two curves can shift independently of one another. If either of them shift, then, in general, income will change; with the result that the whole schematism based on the assumption of a given income breaks down … In truth, the classical theory has not been alive to the relevance of changes in the level of income or to the possibility of the level of income being actually a function of the rate of the investment.

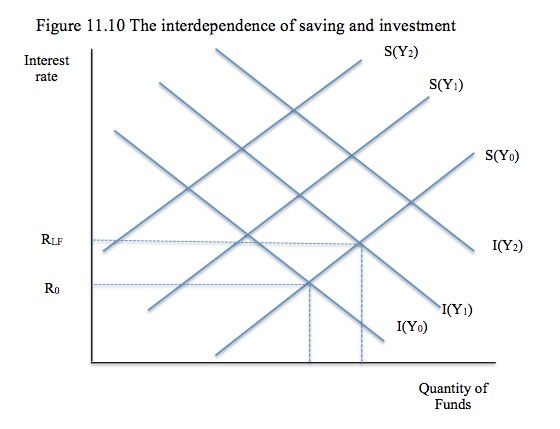

Keynes’ diagram had investment and saving on the vertical axis and the interest rate on the horizontal axis. To maintain continuity with Figure 11.7, we reproduce his graph but reverse the axis.

Relating Keynes lengthy argument (in the last quote) to Figure 11.10 is straightforward. The family of saving functions, S(Y0), S(Y1), and S(Y2) – are drawn for different levels of income (with Y2 > Y0). For each saving function, say S(Y0), the curve shows the level of saving at the level of income for each interest rate level.

The family of investment functions, I(Y0), I(Y1), and I(Y2) – show that when investment is higher, national income rises.

The loanable funds equilibrium, say at Y0 would be at the intersection of S(Y0) and I(Y0), generating an interest rate of R0.

Loanable funds theory, however, did not allow for changes in national income to impact on saving in this way. Accordingly, imagine investment moves from I(Y0) to I(Y1). We know that the shift in investment will drive up national income because investment is a component of aggregate demand. The loanable funds doctrine would argue that the shifting investment function would move along the saving function (S(0) and the interest rate would increase to RLF.

The rise in the interest rate would be necessary, according to loanable funds theory, to eliminate the excess demand for funds at R0 arising from the rise in investment.

Keynes argued that if saving is a function of national income then the Classical approach fails to describe the adjustment in interest rates. He said (page 180) that “the above diagram does not contain enough data to tell us what its new value will be; and, therefore, not knowing which is the appropriate … [saving function] … we do not know at what point the new investment demand-schedule will cut it”.

We have specified that S(Y1) is the appropriate saving relationship at national income Y1, which coincides with the increase in output associated with the boost in investment spending. But that insight is missing in the loanable funds doctrine.

In other words, the loanable funds doctrine could not explain movements in interest rates and a new theory was required. It was at this point that Keynes proposed the concept of liquidity preference as the foundation of his theory of interest rates.

To recapitulate, Keynes found that once we realise that investment and saving functions will shift when national income changes, the theory of interest provided by the loanable funds doctrine failed because it provided no way of knowing how far the investment and saving functions might shift with changes in national income.

This is because the Classical theory considered the level of national income to be constant at the full employment level. Their employment theory was based on their abiding faith that real wage movements would ensure the demand for and supply of labour were in balance and full employment constantly generated.

It was obvious that national income and employment were not constant and certainly during the Great Depression, the mass unemployment demonstrated that enduring departures from full employment were a basic feature of the monetary system. With investment and saving also moving with shifts in national income, Keynes concluded that a theory of interest rates had to be found elsewhere.

Liquidity Preference and Keynes’ Theory of Interest

Liquidity preference was a concept introduced by Keynes to provide the basis for an alternative theory of interest to that found in the loanable funds doctrine. He considered that a theory of interest had to be ground in an understanding of the way in which money and financial markets operate – in particular, the way in which people and firms adjust their wealth portfolios of money and bonds.

Recall that the Classical Theory of Interest considered the interest rate to be a real rather than a monetary variable. Savers were paid interest as a reward for abstemious behaviour – foregoing the consumption of real goods and services now and allowing these resources to be invested in order to building productive potential.

How can borrowers afford to pay interest? For the Classical economists the answer was easy. By using the savings of households, firms could become more productive in the future through the accumulation of capital and the interest paid came from the extra real goods and services that the economy could produce.

So savers enjoyed a premium in terms of higher future consumption of real goods and services made possible by the increased investment that the borrowing allowed. Saving was a real act – the foregoing of consumption of real goods and services now – as was investment – the construction of capital leading to increased goods and services in the future.

For Keynes, the interest rate was a monetary rather than a real variable, which was an important input into a plethora of financial decisions that people made in determining the form of their wealth portfolios.

In contrast to the loanable funds doctrine, which believed the rate of interest determined the flow of saving and investment in the economy, Keynes believed that the level of effective demand determined saving via the propensity to consume. Once aggregate demand is known, then the level of consumption was determined by the resulting national income level.

In – Chapter 13 The General Theory of the Rate of Interest – of his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Keynes said that the “propensity to consume … determines for each individual how much of his income he will consume and how much he will reserve in some form of command over future consumption” (PAGE REFERENCE).

The “command for future consumption” is what we call saving and is a residual from the act of consumption, which is largely driven by movements in national income (and taxation). The interest rate does not determine this flow.

So what impact does the interest rate have?

Keynes then noted (PAGE REFERENCE):

But this decision having been made, there is a further decision which awaits him, namely, in what form he will hold the command over future consumption which he has reserved, whether out of his current income or from previous savings. Does he want to hold it in the form of immediate, liquid command (i.e. in money or its equivalent)? Or is he prepared to part with immediate command for a specified or indefinite period, leaving it to future market conditions to determine on what terms he can, if necessary, convert deferred command over specific goods into immediate command over goods in general? In other words, what is the degree of his liquidity-preference – where an individual’s liquidity-preference is given by a schedule of the amounts of his resources, valued in terms of money or of wage-units, which he will wish to retain in the form of money in different sets of circumstances?

Instead of interest being a payment for “waiting” as in the loanable funds doctrine, Keynes considered it to be a payment a person received for shifting their wealth from liquid money holdings (cash) to some less-liquid financial asset.

The concept of liquidity preference was introduced by Keynes to explain how people made the choice concerning the composition of their wealth. Holding wealth in its most liquid form (money) had advantages – it was risk free – but it also earned no interest and inflation could deflate its value.

The alternative would be to hold some or all of one’s wealth in, say, bonds, which attracted an interest premium. What might motivate a person to invest in bonds, which were less liquid and carried risk that their capital value could fall with adverse market movements (an excess supply).

The interest rate was the reward for the inconvenience of storing one’s wealth in a less-liquid form and the risk of capital loss.

The important point is that for Keynes, the rate of interest did not determine aggregate savings but influenced the way that any savings were prorated between liquid and less-liquid financial assets.

The interest rate also ensured that the demand for liquidity (money holdings) was equal to the supply of money. We will return to this issue in Chapter 14 when we discuss money and banking.

As we will see in Chapter 12, the rate of interest also influences the level of national income because it is one of the variables that influences the decision by firms to invest in productive capacity.

The important point of Keynes’ attack on the Classical theory of interest was that it debunked Say’s Law, which meant that there was no automatic, market mechanism in a capitalist monetary economy that would ensure that all goods and services supplied would be consistent with aggregate demand.

It was then understandable that such economies could over-produce goods and services as a result of the aggregate demand expected by business firms was overly optimistic. As a result, firms would have unsold inventories and their adjustments to the lower realised aggregate spending would lead to output, income and employment cuts.

Conclusion

Tomorrow I will be introducing the concept of the macroeconomic demand for labour curve, which is derived from an understanding of different points of effective demand to round off Keynes and the Classics (for now).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

A cosmetic correction on this blog post. In this sentence:

“We have specified that S(Y1) is the appropriate saving relationship at national income Y1, which coincides with the increase”

the HTML tag is not closed after the second Y1, which makes the rest of the post appear as subscript as well, making it difficult to read.

Regards

Thanks Tristan

Fixed now.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

Honda UK a prime example of your last sentence.

“So savers enjoyed a premium in terms of higher future consumption of real goods and services made possible by the increased investment that the borrowing allowed. Saving was a real act – the foregoing of consumption of real goods and services now – as was investment – the construction of capital leading to increased goods and services in the future.”…”in what form he will hold the command over future consumption which he has reserved, whether out of his current income or from previous savings. Does he want to hold it in the form of immediate, liquid command (i.e. in money or its equivalent)? Or is he prepared to part with immediate command for a specified or indefinite period, leaving it to future market conditions to determine on what terms he can, if necessary, convert deferred command over specific goods into immediate command over goods in general?, KEYNES.

Does MMT account for the fact that this is not relevant as “money now is not involved in “lending” (Not even the alleged 10%) for as Frederick Soddy would state, that they are “Fictitious Lenders” because they are creating a second demand on the goods and services that they have in storage.

Justaluckyfool (google account)

There is a question that I have been pondering on recently, related to the ideas about loanable funds. It’s to do with the question about the effects of the level of net financial assets in the private sector and how they are distributed.

If a firm or householder borrows money, the loan can be repaid only if they have customers to buy what they have to offer: goods or labour. The aggregate of the loans is reduced only if there are potential customers with positive net financial assets. This means that whether the borrowers are credit worthy in aggregate depends on the aggregate net financial assets of the private sector and whether those assets are owned by entities with a high enough propensity to spend.

This argument does not support the loanable funds theory as it is usually applied. If the assets lie with the banks, they are not likely to help because the banks have a low propensity to spend. However, it does raise the question of what is an efficient level of financial assets in the private sector and whether we should be concerned about an accumulation caused by continual government deficits. As well as the level of assets, we should also think about their distribution. The hypothesis is that if they are concentrated in a small section of the private sector, in particular with the banks, that is not a good thing for the health of the economy.

Bond sales don’t fund government spending.

As for the banks – simply get rid of them,