It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Keynes and the Classics – Part 3

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text during 2013. Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

I am currently working on Chapter 11 which opens like this:

Chapter 11

11.1 Introduction and Aims

In Chapter 10, we discussed issues relating to labour market measurement. In this Chapter we will focus on theoretical concepts that underpin the measurement of economic activity in the labour market and the broader economy.

The Chapter has five main aims:

- To explain why mass unemployment arises and how it can be resolved.

- To develop the concept of full employment.

- To consider the relationship between unemployment and inflation – the so-called Phillips Curve.

- To develop a buffer stock framework for macroeconomic management (full employment and price stability) and compare and contrast the use of unemployment and employment as buffer stocks in this context.

- To more fully explore the concept of a Job Guarantee (employment buffer stock) approach to macroeconomic management.

NOTE:

At present, I am outlining the Classical theory of employment determination and output – which is the basis of their denial of involuntary unemployment. In the section last week – Keynes and the Classics – Part 1 – I explained how the Classical system conceives of labour supply and demand and how these come together to define the equilibrium level of the real wage and employment.

Yesterday – Keynes and the Classics – Part 2 – we showed how the labour market determined the level of employment and real wage, which in turn, via the production function set the real level of output.

In other words, all the major real variables in the macroeconomics system were considered to be determined by the labour market and the production technology – a supply-side approach.

We also introduced the concept of unemployment into the Classical system and saw that it could only be a temporary phenomenon if real wages were flexible. Only so-called institutional rigidities such as trade unions and government minimum wage legislation could lead to a situation where unemployment was persistent.

We then started to see why the Classical system denied the possibility of generalised over-production – and in that context introduced the Classical theory of interest via the loanable funds doctrine.

That is where I am picking up from today. Note Section 11.9 is a slightly revised version of yesterday’s text – to get me rolling again!

NEW TEXT STARTS TODAY

11.9 The loanable funds market – Classical interest rate determination

The Classical theory of interest rate determination provided them with a mechanism for denying the possibility that there could be a generalised deficiency in planned aggregate spending, which would result in idle productive capacity and persistent unemployment.

They admitted that specific goods and services could be “over-produced” relative to the preferences of the consumers and firms but believed that rapid market adjustments would ensure there could never be a generalised glut .

The denial that generalised over-production could occur has become known as “Say’s Law” after the French economist Jean-Baptiste Say, who popularised the view.

The idea is sometimes summarised by the epithet – “supply creates its own demand”. The logic is that by supplying goods and services into the market, beyond the output intended for own-use consumption, producers are signalling a desire to exchange their surplus output for other goods supplied into the market.

Using the terminology developed in Chapter 9, and assuming for simplicity a closed economy without a government sector, which is the typical depiction of the Classical system, we know that in equilibrium, the total flow of spending in the economy is equal to total real GDP and national income (Y).

Total spending is the sum of consumption (C) and investment (I):

(11.6) Y = C + I

Equilibrium requires that the flow of real output (Y) is sold in each period.

National income is either consumed (C) or saved (S) which allows us to write:

(11.7) Y = C + S

In equilibrium:

(11.8) C + I = C + S

Which means that the equilibrium condition is S = I, or planned saving is equal to planned investment. This means that all goods designed to be consumed are sold and the remaining national income is equal to investment (designed to provide for future consumption).

The Classical system considers that withheld consumption in each period is matched by (planned) investment spending given that the saving is just a signal that consumers wanted to consume in the future. Firms are thus assumed to invest in future productive capacity to ensure they can meet that demand.

From an existing equilibrium, imagine that the desire to save rose. Consumption would fall in the current period and to maintain the equilibrium output level planned investment would have to rise.

What mechanism exists that would bring planned saving and planned investment into equality each period to allow for shifts in, for example, consumer behaviour (a rise in the desire to save in this case)?

Ignoring questions relating to the logistics of how an economy might quickly shift between the production of consumption and investment goods, the answer lay in the way the loanable funds market operated.

The theory of loanable funds – which is the Classical theory of interest rate determination – provided the Classical system with the vehicle to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply. The continuous equilibration would be achieved by interest rate adjustments, which would always bring planned saving and planned investment into equality as household and firms preferences changed.

The loanable funds market is really a primitive depiction of a financial system. The interest rate (r) is a price that ensures that planned investment is equal to planned saving in any period and is determined within the loanable funds market.

Savers (lenders) enter the market to seek a return on their savings to enhance the future consumption possibilities. Equally, firms seeking to invest (borrowers) enter the loanable funds market to get loans.

The interest rate that is determined in this market provides the return to households for their saving and determines the cost of borrowing funds for investment.

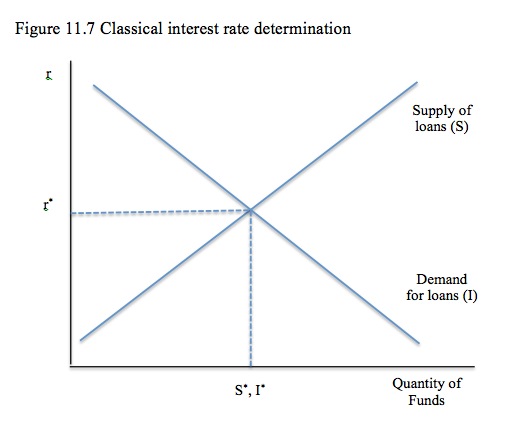

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds. The supply of loans is derived from current saving which is assumed to be positively related to the interest rate. As the interest rate rises, the return on saving rises and so the supply of funds (saving) rises (and current consumption falls).

The demand for funds comes from borrowers who wish to invest in houses, factories, and equipment among other productive projects. Firms form expectations of future returns that they will derive from different projects and rank the profitability of projects for the current cost of funds. As the cost of borrowing (the interest rate) rises, the demand for funds falls because the net return on the planned projects diminishes.

In other words, the demand for loans (investment) is negatively related to the rate of interest. The higher the rate of interest, other things equal, the lower will be investment.

The interest rate adjusts to ensure the supply of funds (saving) equals the demand for loans (investment). In Figure 11.7, the equilibrium interest rate is r* per cent, and this corresponds with equilibrium saving (S*) and investment (I*).

If the interest rate was below the equilibrium rate then the volume of funds demanded from the loanable funds market by would be borrowers would exceed the supply of loanable funds and competition among the borrowers would force the interest rate up. As the interest rate rises, planned saving would increase and planned investment would decline. At the equilibrium interest rate, the imbalance between supply and demand would be eliminated and planned saving would equal planned investment.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

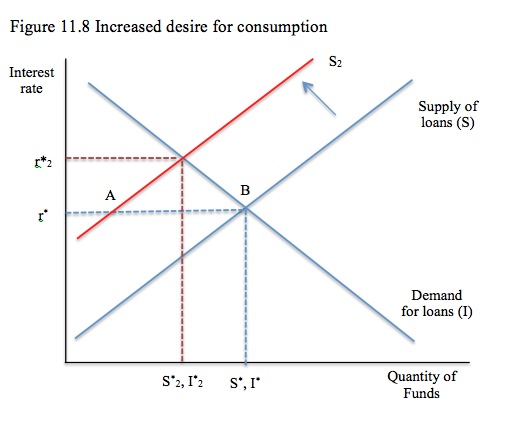

Figure 11.8 shows the impact on the interest rate and the equilibrium level of saving and investment when households decide to consume more of their income in the current period. In this circumstance, the Supply of Loans (S) shifts to the left (say to S2).

At the previous equilibrium interest rate r*, there is now an excess demand for loans equal to the distance AB. Competition for the scarce funds drives the interest rate up and a new equilibrium is established at r*2 per cent, and this corresponds with equilibrium saving (S*2) and investment (I*2).

You should be very clear that the real GDP level does not change as it is determined by the real wage and employment equilibrium set in the labour market.

What changes in the Classical system is the composition of final expenditure and output rather than the total flow. The lower saving is replaced by higher consumption and investment contracts accordingly.

You might also wonder how an economy could make these shifts quickly given that production of consumption goods and services would require a different mix of capital than the production of capital goods. We will discuss that point later.

You should now be able to articulate a story of what might happen should the borrowers expect stronger revenue flows from investment projects or consumers become more cautious and decide to save more of their income.

As a final observation, the Classical system considered the interest rate to be a real variable which adjusted to bring real aggregate demand into line with aggregate supply (via the loanable funds market).

Thus the entire real side of the simple economy is explained in the Classical system without reference to money. Real GDP, national income, employment, the real wage and the interest rate are all determined in the Classical system once we know the state of technology and the preferences of households between work and leisure and consumption and saving.

As we will see, the only function the introduction of money serves in the Classical system is to determine the aggregate price level (and the inflation rate). In the economics literature this separation in the explanation of the real side of the economy and the nominal side (price level determination) is referred to as the classical dichotomy.

11.10 Classical price level determination

To complete the Classical system, we consider their conception of aggregate demand, which allows the system to determine an aggregate price level.

While the output level once the real wage and employment is determined in the labour market and the loanable funds doctrine ensures that real aggregate demand will be sufficient to absorb that level of output, the question that remains is how are the nominal variables in the Classical system determined.

The two key nominal variables are the aggregate price level and the money wage rate. The determination of the money wage follows once we know the price level because the real wage is just the ratio of nominal wage to the price level.

The Classical system explains the determination of the price level by reference to the Quantity Theory of Money. Money is exclusively a means of exchange to overcome the problem of double-coincident of wants in traditional barter models. For example, a plumber who desires the services of an electrician, no longer has to find an electrician who simultaneously desires the services of the plumber.

A given nominal stock of money (Ms), which is a sum of dollars, is considered to be moved between individuals as various transactions are made during some period. The number of times the stock of money turns overs each period in the course of these transactions is called the velocity of circulation (V).

The product of the stock of money and the velocity of circulation (MsV) must therefore equal the total nominal value of real output in a given period. The total nominal value of output is the product of real output (Y) times the price level (P). You will note that this is the definition of current price GDP, which we analysed in Chapter 6.

The Quantity Theory of Money is thus captured by the following expression:

(11.9) MsV = PY

The product MsV is a nominal amount and represents total nominal aggregate demand in a given period, whereas the product PY represents the nominal value of aggregate supply in the same period.

The Classical system assumed that V was constant being determined by spending habits and other shopping customs (including the time of wage and salary payments).

Further, given that the Classical system assumes that the real side of the economy is determined without reference to the stock of money and that real wage flexibility ensures that full employment output will be supplied in each period (as a result of continuous labour market clearing), then Y is also assumed to be fixed in each period.

It becomes clear from Equation (11.9) that if V and Y are fixed, then changes in Ms will cause changes in P.

The Classical system also assumed that the central bank controlled the nominal stock of money in circulation and thus were in a position to determine the nominal value of total spending.

In Chapter 15 Money and Banking, we will examine the concept of the money multiplier, which is the theorem that the Classical system relies upon for their assumption that the central bank can control the money supply. We will learn that there is in the real world the assumptions that underpin the concept of the money multiplier do not hold and that the central bank is unable to control the stock of money in the economy at any point in time.

But for now, we continue to assume that the central bank can control Ms. It follows that with the real variables determined in the labour market, the only variable that the central bank (government) can influence is the price level.

This idea resonates throughout the history of economic thought and as we will see later in the Chapter when we consider the Phillips curve, it led to the current policy resistance to the use of fiscal policy and the promotion of monetary policy as the primary counter-stabilising policy tool.

It follows logically that if V and Y are fixed in any period, then if the central bank was to accelerate the growth in the money supply (Ms) then all it would accomplish was an accelerating growth in the price level, which we call inflation. This theory thus became the central authority for the claims that inflation is caused by lax monetary policy.

11.11 Summary of the Classical System

The simplified Classical system has the following features:

- The labour market is continuously cleared as a result of real wage flexibility.

- Labour demand is determined by the state of techology, which is embodied in the production function and labour supply is determined by the preference by workers for income and leisure. The real wage is the price of leisure.

- The real variables in the Classical economy – real wage, employment, real GDP and the interest rate – are thus simultaneously determined by the labour market clearance.

- The nominal side of the economy – the price level and money wage level – are determined by the stock of money that the central bank is assumed to control. The more money there is in the economy relatively to the given real output, the higher is the price level.

- There can be no involuntary unemployment in this system because real wage flexibility ensures that a continuous state of full employment is maintained. Any persistent unemployment must be due to real wage rigidities that prevent it from adjusting to the respective labour demand and labour supply conditions.

- The only effective role for government policy is to ensure the money supply growth is not excessive and to ensure that the labour market is flexible so that the real wage can balance demand and supply.

11.12 Pre-Keynesian criticisms of the Classical denial of involuntary unemployment

Understanding the meaning of involuntary unemployment requires a prior understanding of the concept of effective demand, which we discussed in Chapters 8 and 9.

The 1936 publication of – The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money – by John Maynard Keynes is credited by most as providing the definitive analysis of the concept of effective demand. Later in this Chapter we will consider how Keynes attacked the Classical view that the real outcomes of the economy were determined by the full employment equilibrium achieved in the labour market via real wage flexibility.

However, the essential elements underpinning the critique of Say’s Law and the modern understanding of involuntary unemployment in a monetary capitalist economy can be found in the work of Karl Marx, particularly in his – Theories of Surplus Value.

Marx, in particular, provided a strong critique of Classical economist David Ricardo, who in his major work – On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation – had championed the ideas of J.B Say, which denied the possibility of generalised over-production in a monetary economy.

In Theories of Surplus Value, Marx launched an attack on Say’s Law, which is the proposition that there could be no general overproduction in a capitalist economy. Marx was intent on showing that a money-using, capitalist economy was prone to economic crises (which we now call recessions) and that unemployment was a inherent tendency of such a system.

Marx was thus opposed to the Classical denial that persistent unemployment could occur. He noted that in denying the possibility of a general glut, Ricardo assumed that consumers had unlimited needs for commodities and any particular saturation (having too much of one good or service) would be quickly overcome by increased demands for other commodities.

Marx started from the proposition that capitalists aim to accumulate ever increasing wealth by extracting surplus value, which is production value in excess of what the workers receive in the form of wage payments. The generation of profit thus requires two actions: (a) surplus value creation as the object of production which aims to reduce the payments to labour (limit their consuming power); and (b) Sale of commodities in market which is limited by the consuming power of society.

So Marx quickly established the inherent contradiction in capitalism and deemed this the precondition for crises. On the one hand, capitalists sought to repress the growth of wages and increase the work effort because that was allowed them to maximise surplus value. But on the other hand, they could only realise that surplus value as money profits if they could subsequently sell the product and the repression of the wage income undermined their chances of achieving that.

Say’s Law was best summarised by Ricardo (in Chapter XX1, Effects of Accumulation on Profits and Interest, of his Principles, Pages 192-3):

M. Say has, most satisfactorily shown that there is no amount of capital which may not be employed in a country because a demand is only limited by production. No man produces but with a view to consume or sell, and he never sells but with an intention to purchase some other commodity, which may be immediately useful to him, or which may contribute to future production. By producing, then, he necessarily becomes either the consumer of his own goods, or the purchaser and consumer of the goods of some other person. It is not to be supposed that he should for any length of time be ill-informed of the commodities which he can most advantageously produce to attain the object which he has in view, namely the possession of other goods; and therefore it is not probably that he will continually produce a commodity for which there is no demand.

Marx started from the observation that Say’s Law was refuted by the fact that crises occur in the real world. Marx saw that sale and purchase are separate actions with separate motivations. He showed that Say’s Law can only hold in barter which denies the essential features of a monetary capitalism.

In barter you may consume your own good whereas in capitalism Marx said that “no man produces with a view to consume his own product” [FIND EXACT REFERENCE]. A capitalist must sell and crises occur when sales cannot be made or only at prices below cost. A capitalist may have produced in order to sell (Say’s Law) but if sales cannot be made how does this help?

Ricardo’s retort was that [FIND EXACT REFERENCE]:

… no man sells but with a view to purchase some other commodity which may be immediately useful to him or which may contribute to future production …

To which Marx responded by saying “What a pleasant portrayal of bourgeois relations!” [FIND EXACT REFERENCE] It was clear to Marx that capitalists aim to sell to transform commodities back into money and realise profits. Consumption is not the aim of the capitalist. He said that only the workers sell commodities (labour power) to consume.

Marx focused on the special role that money plays and demonstrated that it is more than a “means of exchange”. It is the medium by which the exchange of commodities falls into two separate acts which are independent of each other and separate in space and time. This is the key to understanding crises in capitalism.

The break between production and realisation can occur because of this separation. For example, the existence of the chain of production and lines of credit means that a merchant may buy cloth on credit, and the farmer sells to spinner, spinner to weaver etc. If the merchant cannot sell, no-one in chain is paid.

Marx’s argument established for the first time that crises manifest as monetary phenomena and mass unemployment was not a voluntary outcome.

Ricardo (Chapter XXI, p.194) said:

… too much of a particular commodity may be produced, of which there may be such a glut in the market as to not repay the capital expended on it; but this cannot be the case with respect to all commodities.

But Marx showed that all commodities can be in oversupply except money. The necessity for a commodity to transform itself into money means only that the necessity exists for all commodities. It is the general nature of the Money-Commodity-Money process that includes the separation of purchase and sale and their unity which invokes the possibility of a general glut.

Ricardo tried to counter this view (Chapter XXI, p. 194):

The demand for corn is limited by the mouths which are to eat it, for shoes and coats by the persons who are wear them; but though a community, or a part of a community, may have as much corn, and as many hats and shoes as it is able or may wish to consume, the same cannot be said of every commodity produced by the nature or by art. Some would consume more wine if they had the ability to procure it. Others, having enough of wine, would wish to increase the quantity or improve the quality of their furniture. Others might wish to ornament their grounds, or to enlarge their houses. The wish to all or some of these is implanted in every man’s breast; nothing is required but the means, and nothing can afford the means but an increase in production.

To which Marx asked – “Can there be a more childish line of reasoning? Marx noted that when there is overproduction (crises) the workers are “less than ever supplied with grain, shoes, etc., to say nothing of wine and furniture.” [FIND EXACT REFERENCE]

Marx thus made a crucial distinction that remains relevant in the modern debate. Overproduction has nothing much to do with absolute needs. The debate is not about whether production can outstrip needs. It is only needs with capacity to pay that count!

So this was the first real statement of the concept of the principle of effective demand that became central to Keynes’ work.

Ricardo would say that if a person wanted some shoes then they could acquire the means to buy them by producing something themselves. But this is a barter economy. So why not just produce the shoes him/herself? In capitalism, when there is overproduction – goods flood the market. But it is the actual producers (workers) suffer from a lack of commodities. It is nonsense to say that they should produce more.

Marx rhetorically asked for an explanation of the connection between “over-production” and “absolute needs” and indicated that capitalist production is [FIND EXACT REFERENCE]:

… only concerned with demand that is backed by ability to pay. It is not a question of absolute over-production – over-production as such in relation to the absolute need or the desire to possess commodities.

Marx’s ideas were thus the precursor to Keyne’s analysis which sought to refute the Classical notion that the real wage and employment was determined in the labour market. In both Marx and Keynes, we see that actual employment is determined by the level of effective demand – that is, in the product market.

Effective demand is the level of output where business profit expectations are consistent with spending plans by consumers and firms. It was identified that there is a limit on profitable expansion of private output. The level of effective demand places a ration on the labour market and there is no certainty that this limit will coincide with full employment, where all workers who want to work can find jobs.

We now turn to the critique of the Classical system provided by Keynes.

[TO BE CONTINUED …]

Conclusion

Next week we will see how Keynes challenged the Classical theory of interest and the idea that unemployment can only occur if real wages are rigid.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. You will note that there are only three questions instead of five. That is a time-saving move by me to reduce the overhead that the blog places on my time. I also plan to develop some new questions and need the time to write new answers.

I hope it will still be a bit of fun though.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Haven’t checked the differences between yesterday’s 11.9 and todays, but got today’s version first time. Much better. Thanks.

Classic economics is so disconnected from reality why bother to try and explain it. Starting to explain a topic by first descibing a theory that is so obviously rubbish does not seem to me to be a good introduction to the the subjuct. When you learn physics the text does not start by explaining why people believed the sun ran around the earth.

Move on.

@Charles Essen

It may be disconnected with reality, but it is still used by practitioners in the field who are not considered generally by most of the field’s practitioners to be either cranks or rebels. Economics has not reached the stage that physics is at. And historians and philosophers of science generally agree that one of the problems with some of the present teaching of introductory physics is its ahistorical approach. And by that, they do not mean going back to pre-Copernican days. The social sciences are historical in character, at least at their present stage of development, and there are excellent reasons for thinking that physics is an exceptionally poor model for economics. A better model, should one wish one, would be theoretical and field studies in ecology.

Well hopefully any future models will have as, a starting point, Stock, Flow consistency and full 4 sector double-entry accounting with the behavioural equations explicity stated every time.

That is the way we are heading I hope ? In the meantime it does no harm, I mean it is essential to understand how we got to where we are now and that, I imagine, is what this is all about.

Addendum:

Philosophically speaking, economics could be said to be at the stage of competing schools, the most prominent of which are the neo-liberal/neo-classical proponents, the post-Keynesians, and MMT. An analogous situation exists within physics in respect of gravity. In the attempt to reconcile the quantum and general relativistic approaches to understanding the nature of gravity, there could be said to be two competing schools, the quantum school and the general relativistic school. Although both have a number of differing approaches to the problem, essentially, each school would like the other to alter its own theoretical edifice to better conform to its own. As both are well supported empirically, neither has so far felt the need to go in the direction of the other. The answer when it comes may well result in altering both theoretical camps, and possibly necessitate the rewriting of introductory physics textbooks.

I have some sympathy for Charles. Reminds me of classical ‘frequentist’ statistical theory and Bayesian probability theory. The former dominated thinking for a century. It is full of roccoco mathematical embellishments to patch up examples where the theory was clearly inadequate (the reason there are hundreds if not thousands of ‘statistics’ is that a new one was invented every time a problem didn’t ‘fit’). BPT is based on a few clear axioms. But, one still had to spend endless hours understanding exactly what was ‘wrong’ with classical statistics, because so many people grew up with it, or were blindly using computer programs based on it. Very painful. And, sometimes one would feel ‘chuck it all’ and just spend time on what is clearly the correct approach.

I too agree pretty much with Charles. The descriptions of old theories are not clearly delineated from the more appropriate MMT. To me, they interrupt the logical flow in the presentation of MMT.

I don’t like to be too critical, though, because what Bill is doing here is important for my understanding of economics and for the rest of the world.

Fantastic breakdown of labour theory of value stuff which goes to the heart of Europes problems since the 1970s………

The complete rejection of a viable rational domestic economy in our already absurdly open fiefdom is seen in this funny little ditty.

http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/opinion/2013/0105/1224328459741.html

“Put differently, the implication of Put differently, the implication of restored economic sovereignty is that the Government must take the lead in setting out a fiscal programme that is both convincing to the markets and politically acceptable to the domestic electorate. Of course, the fiscal programme must also meet the minimal fiscal targets for 2014 and 2015 set out in the troika agreement and satisfy the new European-level appraisal system but these are consistent with a considerable range of fiscal strategies, so that domestic leadership remains paramount is that the Government must take the lead in setting out a fiscal programme that is both convincing to the markets and politically acceptable to the domestic electorate. Of course, the fiscal programme must also meet the minimal fiscal targets for 2014 and 2015 set out in the troika agreement and satisfy the new European-level appraisal system but these are consistent with a considerable range of fiscal strategies, so that domestic leadership remains paramount”

restored economic sovereignty ?

Right yeah boy

What complete and utter bollox.

These are dark dark market state days.

“politically acceptable to the domestic electorate”

That covers a multitude. Maybe it just means doesn’t start riots in the streets.

@Andy

Those guys cannot even conceptualize a rational domestic economy.

He is a young guy – maybe he is just ignorant of the production / consumption loop

It pains me to say this but we should never have left the Sterling zone in 1979 as instead of being open (&abused ) & integral to the British economy we became a even more open & absurd economy

In Cork city the traditional Industry went into immediate decline while in 1980 Apple computers (the new economy) kept the show on the road for a while.

But something very deep was happening to the internal economy…….from fishing to the pubs (as labour became more expensive (within a Hard inflexible currency which they eventually printed but too late in 1986) the retail pub trade began to decline as people drank at home)

The late Great Frank Hall warned us about the rise of this German style Managerial style “democracy”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GBXtWetS1Jk

Starts at 11.00 if you can understand the Cork Accent.

“I hear our minister is sacking imaginary workers”

at 17.30

The minister for inactivity speaks himself – Gene Fritz

Gene Fitz was his real name – notice the play on words.

Frank Hall was trying to get this point across to the local hicks all those years ago – most did not get it.

They became a victim of Euro Soviet propaganda.

PS Andy

The other side of the debate remains shallow and of course completely misses the point…………

http://www.irisheconomy.ie/index.php/2013/01/05/conor-killeen-on-how-to-negotiate-with-germans/#comments

These guys represent internal capital claims on the now almost totally destroyed economy – so the debate is a kind of strange twisted vortice.

Post 1979 especially these guys have gained almost total power – they depend on the tit of Angela for their sustenance.

Bond Eoin Bond (at least is honest on who he represents)

@ Fiat

“14b shortfall =dependency.”

Bang.

Ireland is a strange twisted creature.

Its no longer a country or sees itself as a country.

Its a larger oceanic Andorra.

I will check it out in the morning.

No problem with the accent. I have relations in the city and county.

Last time I was over, they were telling me about the joys of the Household tax, introduced last year.

What most affected me though was the acceptance of their lot. I saw very little evidence of anger or hope.

It was very depressing.

The essence of the problem may be the fact that the governments have absorbed the absolute right and monopoly to a currency that turns out to be more and more the means to achieve central planning of the economy. I think I heard once about the success of central planning, or was that a illusion on my part?

Watch out for the false Irish Greenbackers……..the false nationalists…..they are nothing of the sort.

Cormac Lucy writes in Colm McCarthys latest piece on the Irish economy blog now that Dorkish voices have been taken out of the equation.

These guys in my opinion represent the Anglo establishment of the Pale.

Cormac Lucey Says:

January 6th, 2013 at 5:19 pm

Policy discussions and policy makers are focussed (understandably) on the most acute symptoms of this crisis:

* Broken public finances

* Broken banking systems

* Depressed spending

* Rampant unemployment

But this focus should not distract us from the essential root of the crisis, which is an INAPPROPRIATE CURRENCY & INTEREST RATE REGIME. Fitch reckon that, if it returned to the Drachma, Greece would merit a 63.9% devaluation (against the US dollar) based on the fundamentals. That figure, even if it were as low as 40%, illustrates the impossibility of what is being required of Greece.

This calls to mind Keynes when he wrote of Britain made an illjudged return to the Gold Standard in the mid-1920s. He wrote:

He [Churchill] was just asking for trouble. For he was committing himself to force down money-wages and all money-values, without any idea how it was to be done. Why did he do such a silly thing? Partly, perhaps, because he has no instinctive judgment to prevent him from making mistakes; partly because, lacking this instinctive judgment, he was deafened by the clamorous voices of conventional finance; and, most of all, because he was gravely misled by his experts.

– “The Economic Consequences of Mr Churchill”, 1925

Fitch estimate that the appropriate devaluation for Ireland would be 15.6% (against the US dollar) but that this could rise to a 50-67% devaluation (against Germany) if Ireland were to depart the Euro under conditions of crisis (which are the most likely conditions of an Irish EZ exit).

The advocates of an internal devaluation solution need to identify how this is to be achieved in Ireland, Greece etc where there are entrenched public sector interests dedicated to preventing any internal devaluation.

In any event, liquidity cannot fix a problem of insolvency. We should have learnt that from Anglo, AIB etc. Even if our creditors are willing to continue funding us, our public finances are insolvent. This is especially so when one considers unaccrued public sector pension liabilities of €116b and unaccrued social security liabilities of €324b. Maybe John McHale might explain where (or indeed whether) these important matters feature in the deliberations of the Fiscal Advisory Council?

Maybe John might consider these words from Reinhart & Rogoff “Debt sustainability exercises must be based on plausible scenarios for economic performance, because the evidence offers little support for the view that countries simply “grow out” of their debts” (“This Time It’s Different”, P 289.)

Indeed maybe John McHale might consider some recent comments from Reinhart. In a recent interview with Barrons magazine Reinhart stated “The orders of magnitude are such that fiscal austerity, together with the ECB easing, won’t be sufficient to deal with the extreme debt overhangs in places like Spain and Ireland. And so, bottom line, we expect to see more credit events, including the writing off of senior bank debt.”

We are not being pulled out of the water by the EU. But nor are we being allowed drown by them. Instead we are being sustained in treading water. That may be good enough for some. It would be certainly be good enough for Frau Merkel, given her electoral timetable. But why on earth should we deem it good enough for us?

None of this is to gainsay the intelligent counter-arguments put by Seamus Coffey and others. There should be no doubt that a EZ exit and debt default would accelerate austerity.

But that isn’t the issue. The issues are (i) whether the accelerated pain of a EZ exit and debt default would be justified by increased longer-term growth prospects and (ii) whether, if only for negotiation purposes, we should not be publicly considering these matters.

Congratulations to Conor Killeen (son of former long-time IDA head Michael Killeen) for breaking with “the clamorous voices of conventional finance” on these questions.”

Dork –

He is partially correct in his Analysis but fails to comprehend (perhaps) the function of austerity.

It is to preserve the present stock of debt and its claims on the now rump economy.

So why engage in redenomination in the first place if the nation can only consume & invest in less stuff after the event ?

“There should be no doubt that a EZ exit and debt default would accelerate austerity”

Simply because they will not issue currency without the bond……interest rates will therefore rise and benefit those with the most claims already. (that was & is the purpose of inflation)

There will be a push for more pointless growth………..rather then sustaining basic life support systems.

Irish people are caught in a trap – between the Anglo cartels methods of extraction and the continental methods.

Its beyond sick.

As there can be no real energy growth given present real world resource constraints – whatever the present establishment they must extract using whatever method suits the guys with claims on the declining capital base.

@ The Dork of Cork

You certainly have a good grip on the matter.

It always is an advantage to take the bitter medicin as soon as possible to avoid deterioration of health. Better an end with horror than horror without end.

The Greece problem could have been solved with maybe 40 Bill. Euros 3 years ago. Today we are talking about 200 plus Bill. Euros.

The problem lays with the politicians that are incapable to sell tough but smart policies to the people and who are unable to live within their budget. I am certain that an electorate that is properly educated on the situation, will select to break free from longterm debt slavery even at the cost of hardship for a few short years.

@Linus

I think those Euros were / are metaphysical

What really mattered was the transfer of a capital / diesel ration to the core from the various euro colonies.

The French banks have done well from the extraction operation and have spent some of the loot wisely at home although I am not so sure their North African investments will do so well given the wave of instability throughout the region.

http://www.sytral.fr/17-projets-plan-de-mandat-2008-2014.htm