It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Keynes and the Classics – Part 1

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text by the end of this year. Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

Chapter 11

11.1 Introduction and Aims

In Chapter 10, we discussed issues relating to labour market measurement. In this Chapter we will focus on theoretical concepts that underpin the measurement of economic activity in the labour market and the broader economy.

The Chapter has five main aims:

- To explain why mass unemployment arises and how it can be resolved.

- To develop the concept of full employment.

- To consider the relationship between unemployment and inflation – the so-called Phillips Curve.

- To develop a buffer stock framework for macroeconomic management (full employment and price stability) and compare and contrast the use of unemployment and employment as buffer stocks in this context.

- To more fully explore the concept of a Job Guarantee (employment buffer stock) approach to macroeconomic management.

[THIS JUST REPEATS THE INTRODUCTION FROM LAST WEEK TO SET THE CHAPTER MAP OUT – TODAY WE MOVE ON TO DISCUSS THE CONCEPT OF FULL EMPLOYMENT – LIKE ALL BOOK DRAFTING EXERCISES THE ORDER OF ARGUMENT EVOLVES AS ONE SETS ABOUT MAKING IT. IN THIS CASE, WE ALSO HAVE TO WORRY ABOUT PEDAGOGY AND THAT ADDS ANOTHER DIMENSION – SO THINGS MIGHT BE A LITTLE DIFFERENT ONCE THE FINAL DRAFT IS SET]

11.5 Involuntary unemployment

Another categorisation that economists have used to describe unemployment is to distinguish between the concept of involuntary and voluntary unemployment. This distinction takes us back to the Great Depression in the 1930s and the debates between John Maynard Keynes and the Classical economists in Britain during that period.

The concept of involuntary unemployment follows directly from our notion of full employment as a maximum employment level that satisfies the preferences of the workers for work.

The idea is that there would be no involuntary unemployment if all persons willing and able to work could find jobs at the prevailing wages in their desired occupation or skill group.

In the The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, John Maynard Keynes said that:

Men are involuntarily unemployed if, in the event of a small rise in the price of wage-goods relatively to the money-wage, both the aggregate supply of labour willing to work for the current money-wage and the aggregate demand for it at that wage would be greater than the existing volume of employment.

Apart from rendering the gender non-specific, the same definition holds today. But what does it mean? Reading literally, it invokes a mental experiment where the real wage is reduced as a result of inflation being greater than the growth in money wages, and one observes firms seeking to hire more labour and workers will to supply more labour hours.

To understand the significance of this definition we have to first take a detour back into what is known as the Classical employment theory, which dominated thinking prior to the Great Depression in the 1930s.

The reason we go back in time is because the Classical system provides the context for understanding the contribution of Keynes and his notion of involuntary unemployment; it allows us to more fully appreciate the concept of full employment outlined in the previous section; and it allows us to understand the contemporary debate more clearly where some economists still persist in retaining the discredited Classical notions when offering policy solutions to unemployment.

11.6 The Classical Theory of Employment

We can construct the Classical system with the help of a few simple equations and graphs. There are four main components to the Classical theory of employment, which we will consider in turn:

- The Classical labour market, which determines the real wage and total employment level (and as a result of the labour force being known we also determine the unemployment rate).

- A theory of production based on the Law of Diminishing Returns, which links the labour market with the product market.

- A theory of saving and investment which introduces the equilibrating role of the interest rate and ensures that there can be no aggregate demand shortages.

- The Quantity Theory of Money which allows the Classical economists to explain the general price level.

The Classical theory of employment begins by considering the production function of the individual firm, which describes how much output the firm will produce for a given labour input, given the stock of capital and other resources that it has at its disposal.

The Classical system assumes, in the short-run, that the stock (and quality) of capital and other resources (land, etc) are fixed and the only variable productive input is labour.

This approach makes a very particular assumption about the relationship between labour and output, which is referred to, by the very important sounding name, as the Law of Diminishing Returns (LDR). While the invocation of the term “law” might sound authoritative even akin to a natural physical law such as gravity, the reality is that the idea is a meagre assertion, and only holds true in the rarified atmosphere of the orthodox textbook. It rarely holds true in the real world of industrial organisations.

According to the LDR, when a firm adds more labour input to the fixed stock of capital, output initially rises but at a declining rate – that is, the incremental output becomes smaller and smaller as units of labour are employed.

In the language of the classical theory, the marginal physical product of labour is positive but diminishing.

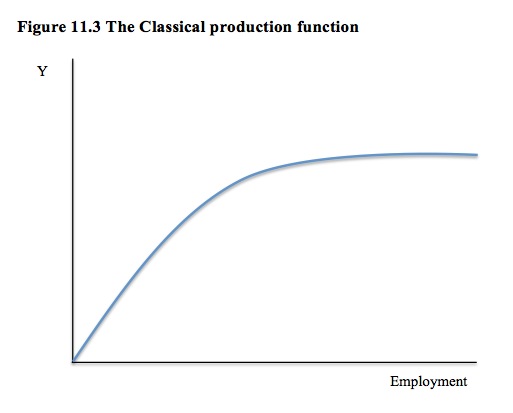

The following diagram plots the Classical production function where real GDP (Y) is on the vertical axis and total employment is on the horizontal axis.

The convex shape of the “production function” is based on the assertion that there are diminishing returns to labour. So as more and more labour is added to the production process, the extra output that is forthcoming diminishes with each extra unit of labour.

Each firm is assumed to be a profit-maximiser, which means they are interested in assessing the revenue they can earn from the extra units of output that each extra unit of employment generates relative to the cost that they incur employing the extra labour.

The Classical model begins by assuming that firms operate in a perfectly competitive product market, which can be summarised by the statement that each firm is too small to influence the price determined in the market for output. As a result, every firm is considered to be a price-taker and it can sell as much output as it likes at that price.

If we assume that the price level is P and the marginal physical product is MP, then the value of the marginal product (that is, how much revenue the firm can expect to earn at each employment level) is given by VMP = P.MP, which converts the physical production output into monetary units.

The VMP curve will be downward sloping with respect to employment because of the assertion of diminishing marginal productivity. The principle of profit maximisation sets rules that govern how much a firm will be prepared to produce and how many units of labour it will employ.

Accordingly, the firm seeks to equate the return it receives from selling the last unit of output produced with the cost of producing that unit of output. We can understand that principle from the perspective of the labour market as meaning that the firm will employ labour up to th epoint where the total cost of the last unit of labour employed exactly equals the value of marginal product (VMP), the latter measuring the revenue the firm gets from selling the marginal product of the last worker employed.

The firm pays a certain money wage rate (W) to the last worker employed. The profit maximisation rule thus means that:

(11.1) W = VMP = P.MP

which then can be re-expressed as:

(11.1a) W/P = MP

Thus, a firm will employ labour up to the point where the real wage (W/P) equals the marginal product of labour.

These concepts form the basis of the Classical labour market, which is the framework that was used to explain both the prevailing real wage rate and the level of employment. Accordingly, total employment is determined by the interaction between labour demand and labour supply. Once the total employment is determined, then the production function tells us how much output will be supplied.

The following equations define the Classical employment and output determination model.

(11.2) Labour demand: Nd = f(W/P) f’ < 0

(11.3) Labour supply: Ns = f(W/P) f’ > 0

(11.4) Labour Market Equilibrium: Nd = Ns

(11.5) Production Function: Y = f(N, K*)

where Y is real output, W is the money wage, P is the price level, K* is constant capital (and other fixed productive inputs). The production function also assumes that technology is constant.

The terms f’ < 0 and f’ > 0 are the so-called first derivatives of the respective functions which we learned about in Chapter 4 Methods, Tools and Techniques. For our purposes here, they tell us about the slope of the respective functions – that is, whether the relationship is an increasing or decreasing function of the real wage.

We conclude that the labour demand function is assumed to slope downward with respect to the real wage (f’ < 0), whereas the labour supply is assumed to slope upwards with respect to the real wage (f’ > 0).

Equations (11.2), (11.3) and (11.4) effectively means that the Classical approach consider that the labour market – the equilibration of labour demand and labour supply – determines both the real wage and total employment.

The real wage is considered to be determined in the labour market, that is, exclusively by labour demand and labour supply. Keynes showed that this assumption is clearly false. It is obvious that the nominal wage is determined in the labour market and the real wage is not known until producers set prices in the product market (that is, in the shops etc).

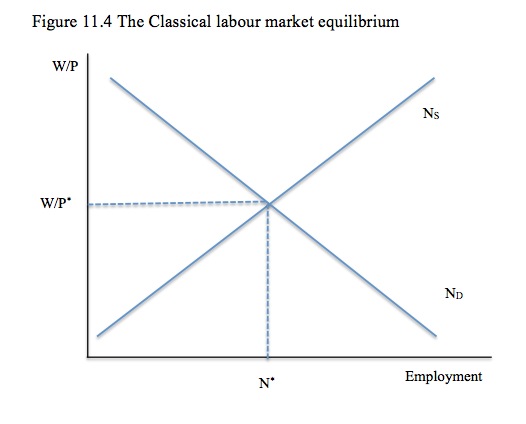

Figure 11.4 shows the Classical labour market equilibrium, where the labour demand and labour supply determine the equilibrium real wage (W/P*) and employment level (N*). The Classical economists considered this level of employment to represent full employment because at that W/P* level, all firms that wanted to employ labour could find sufficient workers and all workers who desired to work could find a firm willing to employ them.

They considered this would be the state that the labour market would gravitate to if the real wage was flexible. As we will see, prior to the Great Depression, departures from this “fully employed” state were only considered to be possible if the real wage was not allowed to move to the equilibrium level (W/P*).

In part, the equilibrium solution of the Classical model required that the labour demand function be downward sloping and the labour supply function be upward sloping with respect to the real wage to ensure they intersected.

Why is the labour demand function downward sloping?

Why is the labour demand function (Nd) downward sloping with respect to the real wage? Equation (11.1a) showed that a profit maximising firm will employ labour up to the point that the real wage is equal to the marginal product.

Given the assertion of the law of diminishing returns, the marginal product declines as employment rises. Therefore to employ more workers, who are producing less at the margin than the last unit of labour employed, the firm will only be prepared to pay a lower real wage rate.

Another way of thinking about this is that the firm has to pay the real wage (which is an equivalent amount of actual product) to the marginal workers and so they will only hire extra labour if the amount the worker contributes to production is more than the real wage. The assertion of diminishing returns assures the demand curve will be downward sloping – so the firm will only be prepared to hire extra workers if the real wage is reduced.

The firm will stop employing at the point where the real wage is equal to the marginal product. This means that the current state of technology helps explain the position of the labour demand curve. If, for example, the firm invested in more efficient capital, then the production function would shift upwards and the each worker would become more productive. As a result, the labour demand function would shift outwards.

Why is the labour supply function upward sloping?

The upward slope of the labour supply curve means that workers will only be willing to supply more labour if the real wage rises. Why would the Classical economists make that assumption?

The Classical labour supply function (Ns) is based on the idea that the worker has a choice between work (a bad) and leisure (a good), with work being tolerated only to gain income. The relative price mediating this choice (between work and leisure) is the real wage which measures the price of leisure relative to income. That is an extra hour of leisure “costs” the real wage that the worker could have earned by working for that hour. So as the price of leisure rises the willingness to enjoy it declines.

Just as the firm is considered to be a profit maximiser, so the worker is assumed to be a utility maximiser such that the satisfaction (utility) he/she derives from an extra hour of leisure (not working) is exactly equal to the satisfaction the worker gains from an extra hour of work and the goods and services that the subsequent income would purchase.

The worker is conceived of at all times making very complicated calculations based on a coherent hour by hour schedule which calibrates how much dissatisfaction he/she gets from working and how much satisfaction (utility) he/she gets from not working (enjoying leisure).

The real wage is the vehicle to render these two competing uses of time compatible at a work allocation where the worker maximises satisfaction.

The Classical analysis motivates the following thought experiment as an attempt to explain what happens when the real wage changes. They assume that the total change can be decomposed into two separate “effects”: (a) a substitution effect; and (b) an income effect.

The substitution effect refers to the impact on the worker’s decision to supply hours of labour when the real wage changes. So if the real wage rises, work becomes relatively cheaper (compared to leisure) and the mainstream theory asserts via the so-called law of demand that people demand less of a good when its relative price rises. So real wage up, less leisure, more work.

However, when the real wage rises, the worker now has more income for a given number of hours of work. The Classical theory then invokes the notion of a normal goods, which are more in demand as income rises (as opposed to an inferior good).

The Classical theory assumes that leisure is a normal good as are other consumption goods the worker might buy with the income he/she earns. As a consequence, as the real wage rises, the income effect suggests that the worker will demand more of all normal goods (because they have higher incomes for a given number of working hours) including leisure. That is the worker will work less!

Therefore, within this theoretical framework, the substitution effect predicts the worker will supply more (less) hours of work when the real wage rises (falls), whereas the income effect, predicts that the worker will supply less (more) hours or work when the real wage rises (falls).

With the two effects working in opposite directions, what determines the overall effect? The conclusion is that despite the mathematical form of the Classical theory of employment and the pretension of analytical rigour, the theory cannot tell us unambiguously which of these two effects dominates.

The result is that the theory asserts that the substitution effect dominates the income effect, which means the labour supply function slopes upwards with respect to the real wage.

The reason they make this assertion is because if the labour supply function didn’t slope upward it might not intersect with the labour demand function, which would then mean that the framework would not have a coherent theory of employment.

[MORE TO COME]

Conclusion

Next week we will continue to build the Classical employment system and then introduce the critique of Marx and Keynes.

Saturday Quiz

The last Saturday Quiz for 2013 will be available tomorrow. Who knows how hard it will be (-:

Happy New Year to all!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Extending the idea behind figure 11.3 to the macroeconomic level (which is what classical system does, far as I can see) is a complete nonsense. 11.3 describes what happens where non-labour inputs (e.g. capital equipment or materials) are fixed for a PARTICUAR FIRM, and numbers employed are INCREASED in that firm. And 11.3 describes that microeconomic scenario correctly.

But that idea is WHOLLY IRRELEVANT at the macro level. In particular, given excess unemployment and ample spare resources for the economy as a whole, a firm that wants to expand can perfectly well expand the amount of non-labour inputs it employs at the same time as expanding the amount of labour it employs. So in that scenario, 11.3 is irrelevant.

The REAL REASON why the marginal product of labour declines as aggregate employment levels rise is the increasing unsuitability of unemployed labour for available vacancies. That arises from the very simple statistical fact that the fewer people there are to choose from for a particular vacancy, the less likely you are to find the ideal candidate.

You could perhaps argue that at or near full employment, employers have difficulty supplying non-labour inputs. But why do they have that difficulty? Easy: they can’t get hold of suitable labour.

And that in turn is why, if you can design an employment subsidy that identifies those “unsuitable” candidates and subsidises them, you can get an increase in aggregate employment. Or to be more accurate, you can improve the inflation / unemployment relationship. I went into that point in more detail here:

http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/19094/

Dear Prof.

Very clear and intuitive exposition of what mainstream economists call the microfoundations of the labour market. Congratulations.

If I may, I would suggest a little extra detail on the subject of labour supply. For instance, by remarking that the model assumes that time is perfectly divisible, workers are supposed to be able to chose to work, say, fractions of hours: say, I could maximize my utility by working 5.02 hours.

But to work arbitrary fractions of an hour, of course, is not feasible in reality. In real life, workers rarely get to determine how many hours their employers are willing to pay them for.

This could be convenient, considering that underemployment is an important subject within the book.

——

Additionally, I have a doubt concerning a detail: the usage of the adjective Classical, which perhaps could induce confusion among your readers.

Wouldn’t it be more convenient to call this model neo-Classical, so as to differentiate it from the classical economists, like Smith, Ricardo, Mills and Marx?

Thanks for your attention.

@magpie

You are right about the difference between the senses of the terms ‘classical’ and ‘neo-classical’ economists in our current day, but for better or worse, in the literature, the original dispute between Keynes and his opponents was referred to as Keynes Vs the classics. The classicists Keynes had in his sights were primarily Marshall and Pigou. But a historical ‘footnote’ or breakout box dealing with this issue, as in the ‘classic’ Gravitation by Misner, Thorne and Wheeler, might not go amiss.