The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Europe is really having a lost decade

I am sick of reading about Europe’s lost decade. For example, in the UK Guardian article (July 27, 2012) – Spanish recession to last until 2014, IMF warns – the economics editor Larry Elliot says that the IMF is “Predicting a lost decade of growth for the eurozone’s fourth biggest economy”. The lost decade terminology emerged to describe the experience of Japan in the 1990s after its spectacularly damaging property crash. But I think it is offensive to use the term in relation to the Eurozone crisis. We are not seeing a lost decade emerge Japanese-style. Rather, we are witnessing a self-imposed humanitarian disaster driven by the ideological arrogance of the Euro elites (aided and abetted by the OECD and IMF). The experience of Japan in the 1990s was nothing compared to what these elites are doing in the name of neo-liberalism. Journalists should stop making the comparison and, instead, call the current crisis in Europe for what it is.

The IMF Survey Magazine article (July 27, 2012) – Spain Needs to Deliver on Reforms to Stabilize Economy – indicates that the IMF has learned very little from the crisis and is intent on getting back to business as normal as soon as they can – ignoring the devastation that the policies they advocate and force onto nations are creating.

I thought the photo that accompanied the article was a disgrace (reproduced below). The caption read “Shoppers in Cádiz, Spain”.

The Survey Magazine article accompanied the major IMF report (released July 2012) – IMF Country Report No. 12/202 – Spain – which reports on the bilateral discussions between the Spanish government and the IMF (part of the obligations of the IMF under its Articles of Agreement).

The Report summarised the latest pernicious austerity program that the EU in partnership with the IMF have imposed on Spain. The July 10 recommendations from the EC amounted to a “loosening the targets for 2012-14” but what remains is still a vicious austerity program

The Spanish government reacted like lapdogs and:

1. Increased the VAT from 18 to 21 per cent (and pushed more low-rated products into the standard rate).

2. Cut the December extra payment to public servants – “equivalent to nearly a monthly wage.”

3. Reduce income tax deductions on mortgages.

4. REDUCE the unemployment benefit to be paid.

5. etc

The IMF Report concludes that:

… the new fiscal consolidation measures to have a significant impact on growth, especially in 2013. While the large role of indirect taxes should lead to a relatively low multiplier, preliminary estimates suggest that the level of output would be lowered by about 1 percent by 2014. Unemployment would also increase, although this might be mitigated by the effect of lower social security contributions and unemployment benefits, as well as the recent labor market reform. The VAT increase, combined with electricity price increases, will also lead to temporarily higher inflation.

The IMF are forecasting a modest return to grwoth in 2014 but on present form that is not a likely outcome. The unemployment rate will remain above 20 per cent at least until 2017.

Study the above quote carefully because it tells you a lot about the IMF mentality. They know that slashing demand will cause the recession to deepen and endure at least for another two years. If the Spaniards thought this year was bad then the next will be worse.

They also know that unemployment will rise. But then they come out – true to form – and insinuate that the increase in unemployment will be attenuated because people will react to the lower unemployment benefits in an adverse manner.

Really? What will these people do instead? With jobs growth continuing to shrink and the probability of getting a job falling do they really think that the unemployed workers are choosing at the margin to be jobless or not depending on the level of the unemployment benefit?

The reality is that cutting the unemployment benefit will make the recession deeper because the capacity of the unemployment to spend will be further compromised.

Unemployment benefits support aggregate demand – albeit in a modest way given the level that is usually offered by governments to their most disadvantaged citizens.

In a recession, if the government is unwilling to take the first-best option and directly create work to prevent unemployment from escalating, then the second-best option is to increase the unemployment benefit and give a boost to demand.

The IMF also think that undermining the job security of workers (the “recent labor market reforms”) also reduces unemployment.

The IMF clearly hasn’t been briefed on this by the OECD. In the face of the mounting criticism and empirical argument, the OECD began to back away from its hard-line 1994 Jobs Study position (which demanded widespread deregulation as the solution to unemployment).

In the 2004 Employment Outlook, OECD (2004: 81, 165) admitted that “the evidence of the role played by employment protection legislation on aggregate employment and unemployment remains mixed” and that the evidence supporting their Jobs Study view that high real wages cause unemployment “is somewhat fragile.”

Then in 2006, the OECD Employment Outlook entitled Boosting Jobs and Incomes, which claimed to be a comprehensive econometric analysis of employment outcomes across 20 OECD countries between 1983 and 2003 went further. The study sample for the econometric modelling included those who adopted the Jobs Study as a policy template and those who resisted labour market deregulation. The Report revealed a significant shift in the OECD position.

OECD (2006) finds that:

- There is no significant correlation between unemployment and employment protection legislation;

- The level of the minimum wage has no significant direct impact on unemployment; and

- Highly centralised wage bargaining significantly reduces unemployment.

The only robust finding that the OECD (2006) demonstrated was that employment protections do not impact on the level of unemployment but merely redistribute it towards the most disadvantaged – including the youth who have not yet developed skills and have little work experience.

That point is obvious. In a job-rationed economy, supply-side characteristics will always serve to only shuffle the unemployment queue. The problem is a shortage of jobs. Unemployment dances very closely to labour demand not labour supply.

But then the IMF operates in a world of concocted evidence and blithe ideological disregard for logical consistency.

In their Spain Report, the IMF claim the problem is the “mounting market pressure and costly market access” although they are forced to admit that Spain:

… is in the midst of an unprecedented double-dip recession with unemployment already unacceptably high, public debt increasing rapidly, and segments of the financial sector lacking capital and market access. Headwinds from household and corporate deleveraging, combined with unavoidable fiscal consolidation and persistent capital outflows, will likely translate into output contractions this year and next.

They claim that “(t)he modest recovery from the 2008-09 crisis gave way to a new slowdown in the second half of 2011 as financial tensions rose” but fail to implicate the austerity programs in this decline.

We learn that “(i)ncome inequality and poverty are on the rise, especially among the young” due to unemployment and the widening disadvantage of temporary workers relative to those on permanent contracts.

At the behest of the OECD and the IMF, Spain led the way in the pre-crisis growth period in creating a dual labour market with an increasing number of workers being denied the chance to enjoy secure, well-paid work. This secondary labour market workforce, already at the bottom of the pile, we disproportionately hammered by the current crisis and government policy responses.

We learn that the household savings ratio improved as the deficits promoted recovery in the early stages of the crisis but have now “declined back towards pre-crisis levels in 2011 amidst weakening disposable income and housing investment”. Once again, the IMF is silent on the obvious point that it was the rising deficits that put a floor in the downward spiral in real GDP growth and provided the conditions (income growth) for households to save and reduce their precarious debt levels.

Any reasonable economist would look at this situation and urge the Spanish government to expand its net spending (increase its deficit) – target wide-scale job creation with an emphasis on getting the youth into work – and generate the conditions where the private sector could more quickly recover from the massive housing crash.

The same economist would urge the government to put into place industry strategies to help the economy rebalance away from private housing construction, which accelerated beyond any sustainable proportions in the lead up to the crisis.

The economist would also urge the government to either cooperate with the central bank (ECB) to minimise yields on its debt or better still stop issuing debt altogether and fund the deficit spending directly from the currency-issuing capacity of the bank.

If the ECB was unwilling to be a growth partner then the economist would recommend the Spanish economy re-create its own central bank and restore its currency sovereignty.

That is the only way that the economy will get out of this mess quickly and put a limit on the rise in unemployment and poverty.

But of-course, the IMF is not a “reasonable economist”. It claims that:

Large fiscal consolidation is … unavoidable.

Which is a lie. If the ECB acted as a growth-oriented central bank then there would be no need at present for any discretionary fiscal contraction. The deficit would decline over time as fiscal-led growth stimulated tax revenue and reduce welfare payments.

Real output could be increased immediately if the government acted responsibility and introduced large-scale public employment programs.

Under the IMF plan, “(o)utput will likely decline this year and next, and over the medium term because of the “fiscal consolidation”. That is, the IMF support the deliberate sabotaging of economic growth and increased poverty.

Further, they project that “(p)otential output growth … [will] … turn negative” partly due to “a permanent decline in capital

accumulation” which means that Spain’s growth trajectory will be damaged for years to come – further reducing the capacity of the economy to generate prosperity.

What madness is it that deliberately undermines prosperity? This is a pure ideological attack on the people of Spain. The Spanish government could very quickly restore confidence in the economy and gets growth going again. Why aren’t they doing it? Because the country is being choked by neo-liberals, backed up by the despicable IMF machine, none of who suffer the costs of their policy approaches.

One of the things a student of economics learns early on is that there are costs and benefits to all resource allocation decisions and policy choices.

The fact is that the none of these agencies (EC, IMF, OECD, ECB) have provided a convincing cost-benefit analysis of their austerity policies. There is no paper I can find where they catalogue the costs of a decade of high unemployment, the destruction of productive capital, the breakdown of public health and safety, and sadly, the breakdown of order in communities, families and individuals.

Where is the cost-benefit analysis of the policies that will leave European youth unemployed for at least a decade – meaning they transit from being teenagers to adults having never had a job; never gaining work experience; and dropping out of the education system admist forced cutbacks to public schools.

The current generation of economists will stand dammed for their actions in the current crisis.

All the IMF can say in the Spain Report is that once again they got it wrong:

The 2011 fiscal slippage was much worse than expected, underlining the challenges of fiscal consolidation at all levels of government.

And given the deteriorating growth, they acknowledge that it will be even harder for the Spanish government to stay on track in its deficit reduction plans.

Their solution?

Staff expects an overall deficit of around 7 percent of GDP, a deviation with respect to target of around 1 1⁄2 percent of GDP. Structural slippage should be resisted, but given the weak growth outlook, it should not be made up in a compressed timeframe. This could imply, for example, immediately taking additional measures of at least 1 percent of GDP on a full year basis to reach a 2012 deficit of about 6 1⁄4 to 6 1⁄2 percent of GDP. The additional measures could usefully include eliminating some VAT exemptions, raising VAT rates (especially reduced rates) and other indirect taxes, taxing the thirteenth salary, and cutting fourth quarter capital expenditure.

That is, when the wound in the head is bleeding more than you planned during the torture the only solution is to get a bigger hammer and bash harder. That should fix it.

The IMF wants more tax increases (“there is considerable scope to reduce tax expenditures and increase indirect tax revenue by broadening the base and raising and unifying rates”) – further cuts in spending (” future public wage cuts to reduce the wage bill”) and more public asset sales (“privatization on remaining assets should be more aggressively pursued”).

They have the audacity to claim that if the austerity is “front-loaded” – that is, tougher now – “should boost market confidence and reduce borrowing need”.

Their proposals in this regard will worsen private sector confidence and increase social instability. I predict that the markets will never be confident with that sort of scenario.

The markets want stable places to invest and prefer growth scenarios.

In the Survey Article, the IMFs mission chief for Spain, one James Daniel is interviewed. I will spare you the agony of reading it.

He just reiterates the nonsensical claim that the austerity merchants are repeating constantly now that the Spanish government has to make:

… sure the measures to reduce the fiscal deficit are as growth-friendly as possible …

With the private sector in retreat, cutting public deficits is never “growth-friendly”. The IMF projections themselves show that the fiscal austerity will undermine growth by at least 1.5 per cent in the coming year.

What they mean is that the aim is to minimise the damage the policy causes.

James Daniel also had the indecency to reiterate the IMF line that mass unemployment is so high in Spain because the labour market is not flexible enough.

And what of the lost decade comparison?

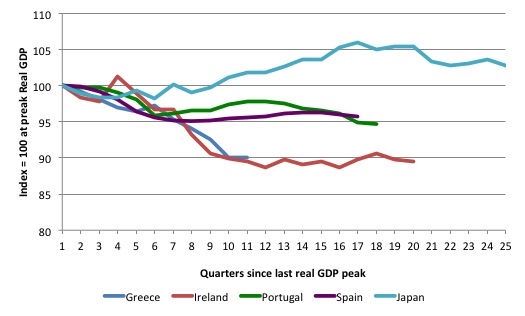

Real GDP

The following graph uses OECD Real GDP data to compare how the current crisis in the four worst-hit EMU nations compares with the crisis that Japan experiences when its property market collapsed in the early 1990s.

The indexes are set to 100 at the respective real GDP peaks and then trace the evolution of the economies in the quarters that preceded the peaks.

The respective peaks in real GDP were September 2008 for Greece; March 2007 for Ireland (hence the longer time series); December 2007 for Portugal; March 2008 for Spain and March 1993 for Japan.

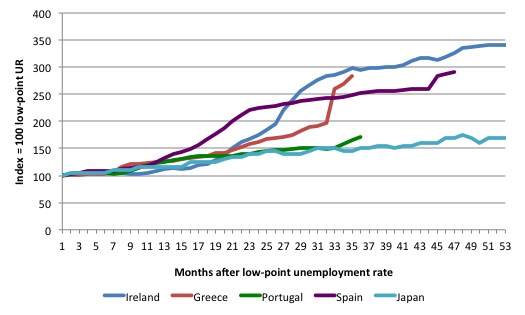

Unemployment rates

The unemployment data came from Eurostat.

The low-point unemployment rates as the crisis hit were Greece 7.3 per cent in May 2008; Ireland 4.3 per cent in November 2006; Portugal 8.2 per cent in April 2008; and Spain 7.9 per cent in May 2007. At the time of its major property bust recession, Japan recorded a low-point unemployment rate of 2 per cent in February 1992.

On July 2, 2012, Eurostat released their most recent unemployment data for May 2012 which showed that the overall Euro area unemployment rate had risen to 11 per cent – the highest in the monetary union’s history.

The data showed that the unemployment rate in Greece (as at March 2012) was 21.9 per cent (now close to 25 per cent); Ireland 14.6 per cent; Portugal 15.1 per cent; and Spain 24.6 per cent (now above 25 per cent). At the same time, the unemployment rate in Japan was 4.4 per cent.

Youth unemployment rates (under 25 years of age) in Greece (March 2012) and Spain (May 2012) were 52.1 per cent and the situation has deteriorated since then.

The following graph compares the evolution of the unemployment rate in the four EMU nations in the current crisis with Japan in the 1990s with the series indexed to 100 at the respective low-point unemployment rates.

Why did Japan perform much better even though its property crash was probably larger than that experienced in Spain or Ireland in recent years?

First, it has its own currency and its own central bank.

Second, it floats the yen.

Third, it used budget deficits deliberately in the early 1990s to buttress aggregate demand. In fact, despite the massive property crash and the retreat of private investment, Japan only had a mild recession – with real GDP growth declining in June 1993 (-1.1 per cent) and September 1993 (-0.5 per cent). There were other quarters during this period where negative real GDP growth was recorded but never two successive quarters of negative growth.

In fact, the next recession, larger than in 1993 came in 1997-98 as a result of the conservatives forcing fiscal austerity (tax increases) on the government as the budget deficit rose.

Once the austerity was reversed in 1998, the economy resumed growth relatively quickly.

Fourth, the rise in unemployment was held down because the government prioritised low unemployment.

Conclusion

There is no comparison between Japan’s low growth decade in the 1990s as it struggled with a spectacular property crash and what is happening in Europe at present.

The former was made possible because the government for the most part used deficit spending to ensure growth was maintained in the face of unprecedented private sector spending cut backs.

The latter is a deliberately created disaster – ideologues running amok. A human tragedy is being created but none of the elites will bear the costs.

Alternative Olympic Games Medal Tally

My Alternative Olympic Games Medal Tally is now active.

I update it early in the day and again around lunchtime when all the sports are concluded for the day.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Any reasonable economist” wouldn’t get much air time in the US media.

Sweden is now being rolled out as the ‘model’ for Europe and a lot of data put forward demonstrating the supposed correlation of neo-liberal reforms with their growth over this recession period.

Given Sweden reset its banks in the mid 90s are we just seeing another private debt bubble and reduction in the wage share, but out of sync with everybody else?

I find the IMF reports refreshing really , in their Irish Missive – they came out and said pretty plainly that they will have to take money from people to make private banks profitable…….

The irony of it all escaped most on the Irish economic blog commentators I am afraid.

We really don’t need Credit banks to produce wealth because they simply don’t – the IMF incredibly indirectly admitted this on their papers – infact they never have.

But they will engage in this wealth redistribution operation because they simply can.

When these European entities became jurisdictions rather then countries there was a certain class of domestic people who gained benefit and local power from enabling these international extraction operations rather then previous domestic wealth redistribution policies which involved some messy politics. – these Guys & Girls and their offspring will become the new ascendancy.

When this operation is all over the private banks will hold all the remaining wealth – they will then spend the stuff into existence again on various follies as there will not only be a lack of rational demand as before – there will be a lack of demand period.

So therefore all “investments” will almost certainly become irrational as there will be no demand signal.

Its a beautiful experiment of chaos production really.

All to sustain a Banks idea of money which is plainly absurd…..their collateral money system.

I think that the whole country is about to collapse, both social and economically. During this period families have been a sort of social cushion, relying heaviliy in fathers and elders. However, if social benefits are cut, this cushion will be gone, and the problem will be exacerbated by the end of the year.

Why oh why they don’t listen to you?

Neil W

The Sweden’s recovery from 90s private balance sheet recession:

http://img185.imageshack.us/img185/2899/unempnetexp.png

Unemployment keep on being high despite economic “sucsses”:

http://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=z8o7pt6rd5uqa6_&met_y=unemployment_rate&idim=country:se&fdim_y=seasonality:sa&dl=en&hl=en&q=unemployment+sweden

Sweden public sector net financial accumulated “savings”, % of GDP.

17,5% 2007

12,5% 2008

19,6% 2009

20,9% 2010

18,4% 2011

17,9% 2012 spring budget estimate

Public sector “savings” % GDP

3,6 _2007

2,2 _2008

-1,0 _2009

-0,1 _2010

0,1 _2011

-0,3 _2012 spring budget estimate

So while Sweden politicians beat their chest about “strong” public finances and an abundance of “savings” the 90% get more and more entrenched in debt. At least since year 2000 about 70% of new house/home mortgage have not been for purchase of home/houses. Aka neoliberal poster-boy, have “sound” public finances payed by indebted households. And of course export driven growth. From 1994 to 2009 if one sum the inflation adjusted net export it sums up to about equal the entire 2009 GDP, a whole year of production that haven’t been consumed by Sweden’s citizens. In the same time we see record unemployment, slashed well-fare, old and demented perish from bedsores, dying infants turned away from medical care by medical gatekeepers to “save” for “sound” public finances. In the same time, mainly Social-democrats, did hand over the financial gains from an entire year of production to the capitalist elite, who started mindless bankster “casinos” in e.g. The Baltic. The mean wealth is 6:e highest but less then 10% owns about 76% of the wealth.

The self-delusion of the people running our economies is truly incredible. Last week I had occasion to listen to a talk by an analyst / portfolio-manager for a major equities fund. His talk was about what we should be doing in the U.S., but during questioning I asked him why we should pursue more austerity in the U.S. (as was his recommendation) given what that policy was doing in Europe. His first claim was that Europe was well on the road to recovery! Asked to explain he said that Euro-bonds would fix everything. When I pointed out that Merkel was opposed to them and that they were possibly a violation of the ECB charter, he said that was just a German negotiation ploy to get an agreement for even more austerity. We eventually got around to talking about Spain and his claim was that anecdotal evidence of a large underground economy was evidence that their situation was not actually as bad as the official unemployment numbers would seem to indicate! I could go on; his other claims were a litany of neo-liberal absurdities (such as blaming U.S. unemployment problems on educators who don’t teach the skills needed to match open jobs and then raise costs which make it a burden for people to get educated at all). He never did explain why he thought we should pursue more austerity in the U.S. …

Thanks much for the ongoing education Bill.

As I see all of this progress, I can’t help but to think of the game of Monopoly. We’re all familiar with the rules. Everyone starts out with the same amount of money, and there are modest increases in the money supply each time anyone passes “Go”. These increases however don’t keep up with the needs of the “Monopoly economy”, and gradually some players get poor as others get rich. All the while however, each Monopoly dollar continues to retain it’s value.

Eventually of course, one player gets all the money, and is declared the winner. At that point, something curious happens: All that money, which until this point had value, suddenly becomes worthless. One player’s success in Monopoly destroys the Monopoly currency.

The IMF and the Euro bosses might better spend their time playing a child’s game. It would teach them more about what they are doing than all their economics education ever did. The Euro is being played like Monopoly, and it will come to a similar end.

The euro reminds one of the US Long Depression and the battle with the international bullionists. Greece should print up some Greecebacks upon which no interest can be received and none charged. Then spend them into the economy with an infrastructure program.

The term they are searching for, but somehow failing to find, is “Depression”.

@Neil Wilson

Swedish private debt/GDP stand at over 240% and climbing. I’d say they have a credit bubble which hasn’t yet burst.

It seems to me Krugman gets one right on Sweden in the 1990’s.

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/03/29/two-faced-sweden/

“I have, in the past, used Sweden’s experience in the 1990s to illustrate the difficulties we face in recovering from a global financial crisis: Sweden recovered from crisis, but it did so only by devaluing its currency and moving from trade deficit to trade surplus, a route that’s not available to the world as a whole (unless we can find another planet to trade with).”

“Strange to say, there’s no mention of the swing in Sweden’s trade, which was equivalent to a 6 percent of GDP stimulus: …”

I don’t agree with more gov’t debt.

The trade in Sweden have always done fine, not even with the “overvalued” fixed exchangerate, before it was let to be so called managed float an sunken, there where any deficit in the trade of gods and services. Last time there was an negative contribution to GDP was 1981 when the oil price peaked.

1990 there was only an export net of +0.8%, of course “alarming” in mercantilist nation. It had sunken from 4.25% in 1984, contributing cases was Plaza Accord and a fixed exhange rate basket where the dollar weighted heavy. These years let the swed workers come back to the real wage level of 1980 and low unemployment.

But yes there was an Current Account deficit, but not due to very bad trade a position. Currency and capital deregulation and a fixed exchange rate made swedens capitalists borrow exuberantly abroad and speculate in real estate in, London, Berlin and so on, at lunatic prices. The locals talked about the crazy sweds. This ballooned the foreign interest payments in the current account. This in. Sweden called that the ordinary sweds was ling beyond their means.

This “stimulus” from net export surplus Krugman is saying saved Sweden have strange effect, as you can see in the image link above unemployment follow the export net as a Siamese twin, the more export surplus the more unemployment. If you squeeze the domestic market with austerity you ca create a export surplus.

Sweden have “always” been a big export nation and high up in the value chain, above Germany.

http://img217.imageshack.us/img217/8417/expcapita2.png

It wasn’t the export industry that was the main victim of the 90s crisis, it was the domestic market, it was there the unemployment exploded and more than 60K small and middle sized companies did go bankrupt in 3 years (in a 8 million country). And it have never really recovered. The high unemployment peaked 1997, the lowered figures after that was much helped by shuffling many to other subsidizing systems, early retirement, longterm sickleave etc. People in working age supported in public systems did go down but remained very high compared to how it have used to be.

The export capitalist in Sweden is an exuberant special interest, dominate every aspect of economic information to politicians and the public. Since there mid 70s they wanted to transform Sweden to the neoliberal model and built up strong institutions. The 90s crisis was their final and total victory. The exorbitant export surpluses that have been since is rarely mentioned in media. If something is touted in media is menace of global competition and the Swede should sacrifice more to be competitive.