I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

The non-existent but remarkable austerity-depreciation mechanism

The conservative lobby (often dominated by Austrian school types) are increasingly running the narrative that neither monetary or fiscal stimulus can engender growth as nations wallow in stagnation. Their rejection of the use of fiscal stimulus – aka spending of one sort or another – would appear to be in denial of the basic macroeconomic rule – one person’s spending is another person’s income – or in a sectoral sense – government spending equals non-government income. Their arguments against monetary policy have some resonance with my own views. But, for example, is any one really going to argue that if the government hired all the unemployed and paid them a stable wage (in excess of any income support they might be receiving) that the shops would not experience rising sales, which, in turn, would stimulate rising orders to suppliers and increased production and higher growth. Are they really saying that all stimulus spending leaves the shores via net exports? While historical evidence is often cited, when one digs further it becomes clear that the evidential basis of the anti-government claims cannot be substantiated. And – the arguments reduces to a rather crude expression of their dislike of government activity.

Most recently there was a Bloomberg Op Ed (August 1, 2012) – Ben Bernanke Could Lose for Same Reason as Olympic Sailor – by that so-called historian Amity Shlaes. I last wrote about Ms Shlaes in this blog – When conservatives reinvent history to suit themselves. She is a selective interpreter of history – to say the least.

In her recent book – The Forgotten Man – she sought to refute the obvious fact that FDR’s New Deal policy substantially reduced unemployment. She purports to show that unemployment did not fall under the major public works programs that were part of the Federal stimulus efforts in the early 1930s.

The only problem is that she deliberately counted the people who were in the job creation programs (that is, working for a wage) as being unemployed.

She also declined to include the most obvious statistic that economists deploy to measure economic growth – real GDP growth – in her analysis.

Of-course on both counts – Real GDP grew rapidly in 1934, 1935 and 1936 – and unemployment fell as the idle workers were absorbed into productive employment by the New Deal work programs. But Ms Shlaes decided to ignore all of that and along the way fudge the jobless numbers to boot.

In the Bloomberg article, she chooses to publicise “some research “pulled together” by two economists at the Bush Institute (where she works). There is very little information available about the Bush Institute but the identities that have publicly linked themselves to it would suggest it is a hive of free market zealots who spent their time crafting “evidence” to support their anti-government ideology.

When I clicked the link in the Shlaes article to see what the book was about I received this message from Firefox (see following graphic), which I took to be some new fangled filter that Firefox has skilfully weaved into its code to protect visitors accessing dangerous and/or fraudulent material. I can’t be sure about that but I was grateful for the relief.

I had previously read the paper – Household expenditure cycles and economic cycles, 1920 – 2010 – that presumably fed into this book. You can download a version of it HERE. I would not bother though – it is 1.1mb and its file size bears no relation to its quality.

Ms Schlaes reports that the faith that Ben Bernanke appears to have in monetary policy as a viable counter-stabilisation policy tool is mis-placed. Her argument is based on:

… the conclusion about the central bank drawn by two economists, the Nobel Memorial Prize winner Vernon Smith and Steven Gjerstad, after a review of the 11 U.S. recessions since World War II and as well as crises abroad.

So really she is parroting their argument which is that “basic premise at the Fed” that along with fiscal policy the central bank “navigates the economy like a ship through something called the business cycle, and that the North Star is data on business investment, such as a measure called ‘gross fixed investment’ (spending on plants, machinery or roads)” is false.

The reason this premise is false (and we are taking their interpretation of the central bank’s thinking without question for the moment) is because “business investment isn’t the North Star to measure progress”.

Instead, in rejecting the term “business cycle” they argue that the real driver of economic fluctuations is “purchases of new single and multifamily homes” – which is what the paper I referred you to is all about.

In the paper they write:

Although expenditure on new housing units is not a large component of GDP – which may explain its limited role in typical macroeconomic accounts of recessions – it is volatile, it has declined before ten of eleven post-war recessions and the Great Depression, it has rarely declined substantially without a recession following soon afterward,3 and the extent of its decline emerges as a good predictor of the depth and duration of the recession that follows.

So their first complaint is that business investment is not a leading indicator of economic activity.

They then claim that monetary policy is not a powerful counter-stabilising policy tool. They write:

We also argue that there are two conditions in which monetary policy is deprived of much of its power: both conditions are present in the aftermath of the recent recession. First, accommodative monetary policy primarily affects new residential construction, and therefore a saturated housing market has only a muted response to monetary easing. Second, when household balance sheets are damaged in the aftermath of a serious housing bubble and collapse, households remain unresponsive to accommodative monetary policy as their focus turns to de-leveraging rather than borrowing for new housing assets or durable goods. In extreme cases the net flow of mortgage funds turns negative: this occurred in both the Great Depression and the Great Recession.

I have no problem with this conclusion. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not prioritise the use of monetary policy as a counter-stabilising policy tool because it operates indirectly (that is, does not stimulate spending immmediately); it cannot be easily targetted; and the distributional effects are uncertain (creditors and debtors are impacted differently by interest rate changes).

Further, the so-called non-standard monetary policy tools such as quantitative easing are based on the false premise that banks are currently not lending because they do not have sufficient liquidity. The claim that by swapping government and other bonds for reserves will lead to more bank lending denies the way banking operates.

It is also a central MMT tenet that when the non-government sector is deleveraging to restore some sense of security to household balance sheets it is unlikely that the demand for credit will be high and that non-government spending will likely be insufficient to restore growth in any immediate time frame.

Please read my blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more discussion on this point.

Ms Schlaes is correct in emphasising that central bankers think they can operate in an effective “countercyclical” manner (that is, against the direction of the private spending cycle) and that “homeowners who owe more than their houses are worth won’t take more loans or spend more money until their budgets look better. So quantitative easing won’t work now”.

She clearly doesn’t know exactly what quantitative easing is although, to be fair, if one takes an uncritical view of what central bankers say in their hype, one might conclude that it was designed to stimulate lending by making more funds available to banks.

The more sophisticated understanding of quantitative easing is that it impacts on the economy by reducing long-term interest rates (by pushing up demand for the assets which drives their yields down). This will only be stimulatory if investors perceive that there are profitable returns in the real economy to be made by borrowing at the lower rates.

The evidence is clear that pessimism over expected revenue streams are outweighing the benefits of lower costs of finance. Further, firms know that they have enough capital in place at present to meet the demands for goods and services coming from the household sector, which itself is being subdued by the huge debt levels, precarious housing market, and the constant threat of unemployment.

Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

So we can all agree that the emphasis on monetary policy as the vehicle to restore aggregate demand growth is misplaced. I would note that the dominance of monetary policy over fiscal policy is a characteristic of the neo-liberal era.

Economists managed to convince governments that fiscal policy was ineffective and likely to increase inflation if used to reduce unemployment and that inflation targetting (supported by passive fiscal stances) was the best way to achieve price stability and maximise real GDP growth.

There was no evidence supporting that mix. It was, in fact, it was a reflection of the neo-liberal hatred for government intervention in the economy and was accompanied by deregulation and other policy initiatives that was justified on the now clearly false claim that self-regulating markets would maximise wealth for all.

Ms Schlaes then jumps a very wide gap – that is, declines to consider whether counter-cyclical fiscal policy should be the primary policy tool to support growth when private spending is weak – and writes that the belief that “procyclicality is supposed to be lethal” – is refuted by the two economists:

Smith and Gjerstad argue that the best course for recovery seems to be for the government to practice austerity, by reducing spending, even during the recession. In other words, to adopt that dread procyclical position. Additionally, countries should focus on recovery through exports, they say, and allow their currency to depreciate to improve terms of trade for exporters.

Apparently, the book authors claim that the “austerity-depreciation mechanism is remarkable”.

So lets dig into this alleged awesome “austerity-depreciation mechanism”.

First, to understand movements in international competitiveness we have to differentiate several concepts: (a) the nominal exchange rate; (b) domestic price levels; (c) unit labour costs; and (d) the real or effective exchange rate.

It is the last of these concepts that determines the “competitiveness” of a nation. This Bank of Japan explanation of the real effective exchange rate is informative.

The nominal exchange rate (e) is the number of units of one currency that can be purchased with one unit of another currency. Movements in nominal exchange rates provide ambiguous signals about changes in international competitiveness for a nation.

To determine whether a nation’s goods and services are becoming more or less competitive with respect to goods and services produced overseas you need to know about:

- movements in the exchange rate, ee; and

- relative inflation rates (domestic and foreign). Economists define the ratio of domestic prices (P) to the rest of the world (Pw) as Pw/P.

Economists normally ignore in this discussion the non-price dimensions to competitiveness, including quality and reliability of supply, which are assumed to be constant.

For a nation running a flexible exchange rate and domestic prices of goods, say in the USA and Australia remaining unchanged, a depreciation in Australia’s exchange means that our goods have become relatively cheaper than US goods. So our imports should fall and exports rise with due allowance for lags in the response.

An exchange rate appreciation has the opposite effect.

Competitiveness can also change if the relative price ratio (Pw/P) changes:

- If Pw is rising faster than P, then local goods are becoming relatively cheaper; and

- If Pw is rising slower than P, then local goods are becoming relatively more expensive.

The inverse of the relative price ratio, namely (P/Pw) measures the ratio of export prices to import prices and is known as the terms of trade.

Movements in the nominal exchange rate and the relative price level (Pw/P) need to be combined to define the real exchange rate which is used to measure a nation’s competitiveness in international trade.

The real exchange rate (R) is defined as:

R = (e.Pw/P)

where P is the domestic price level specified in say, $A, and Pw is the foreign price level specified in foreign currency units, say $US.

The real exchange rate is the ratio of prices of goods abroad measured in $A (ePw) to the $A prices of goods at home (P). So the real exchange rate, R adjusts the nominal exchange rate, e for the relative price levels.

For example, assume P = $A10 and Pw = $US8, and e = 1.60 (defined as the number of $As which are required to buy one unit of the foreign currency). In this case R = (8×1.6)/10 = 1.28. The $US8 translates into $A12.80 and the US-produced goods are more expensive than those in Australia by a ratio of 1.28, that is, 28 per cent.

A rise in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e depreciates; and/or

- Pw rises more than P, other things equal.

A rise in the real exchange rate should increase a nation’s exports and reduce its imports.

A fall in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e appreciates; and/or

- Pw rises less than P, other things equal.

A fall in the real exchange rate should reduce our exports and increase our imports.

So what has been happening in the US?

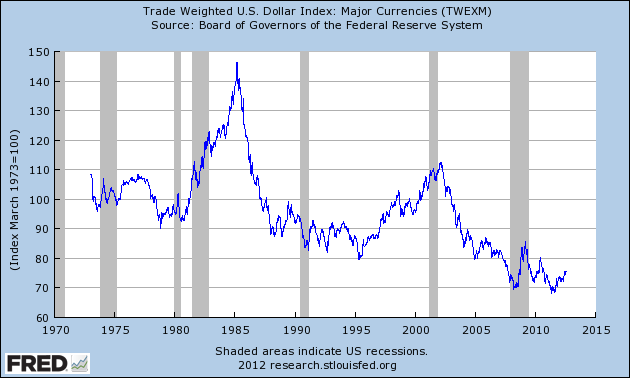

The first graph is from the excellent St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank FRED Economic Data and shows the Trade Weighted U.S. Dollar Index: Major Currencies (TWEXM) – which the US Federal Reserve define as “Rates in currency units per U.S. dollar”.

So according to the way the parity is being expressed, a rising index indicates the US currency is appreciating tion and a falling index indicates it is Depreciating. The shaded areas indicate peak to trough. The data is only available from 1973 and shows the monthly rates (averaged daily rates) of the US dollar against a trade-weighted basket of major currencies.

For more information on the derivation of the series – see Indexes of the Foreign Exchange Value of the Dollar – which appeared in the Winter Edition of the 2005 US Federal Reserve Bulletin.

The Federal Reserve Bank paper says that the major currency units – “the euro, Canadian dollar, Japanese yen, Brit- ish pound, Swiss franc, Australian dollar, and Swedish krona – trade widely in currency markets outside their respective home areas, and these currencies (along with the U.S. dollar)” and for this reason “are referred to by the Board’s staff as ‘major’ currencies”.

The graph shows that for the major recessions since the early recessions, the nominal US exchange rate has actually appreciated in most recessions (only the 1990s recession saw the nominal exchange rate depreciate in any substantial manner, although before the trough was reached it had started to appreciate.

But as noted above to gauge the movements in international competitiveness, we need to use the real exchange rate.

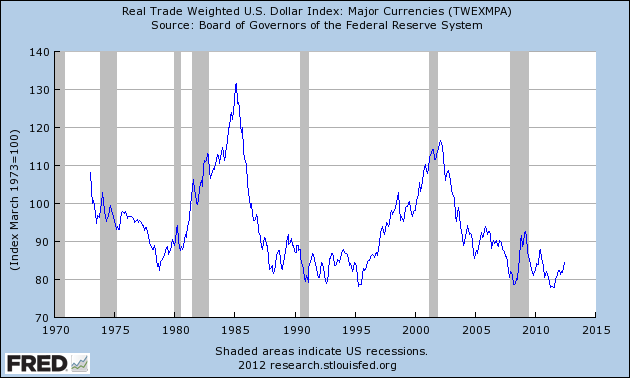

The next graph shows the – Real Trade Weighted U.S. Dollar Index: Major Currencies (TWEXMPA). The real series is adjusted using consumer price index data which is only available on a monthly basis.

The evidence is that the real exchange rate has not depreciated in any significant manner during US recessions since the 1970s. For example, the US Federal Reserve Bulletin article notes that:

The period of dollar appreciation in the early and mid-1980s and the subsequent prolonged period of dollar depreciation are tracked by the rise and subsequent fall of the real major currencies and real broad dollar indexes.

These were counter-cyclical movements (US dollar appreciating when economic activity was deteriorating) in the real exchange rate.

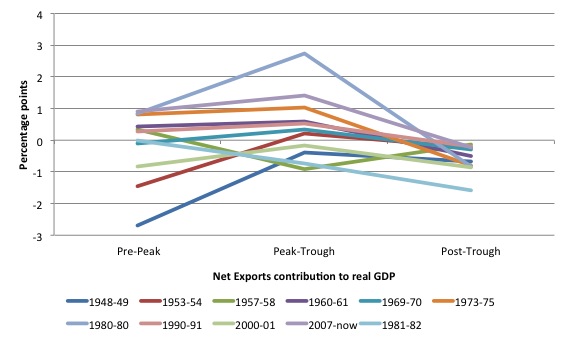

I also examined the quarterly National Accounts data provided by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis from 1947. I considered the contributions to real economic growth in the US for time periods which contained 4 quarters before the peak and 4 quarters after the trough (plus the peak-to-trough period) for the eleven official recessions since that time.

The standard business cycle dating for the US comes from the US National Bureau of Economic Research who provide a table of US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions.

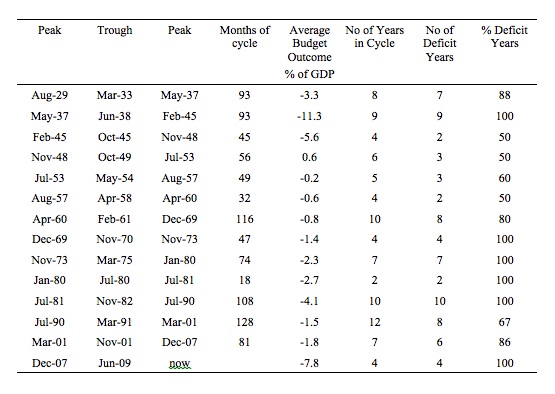

The following table presents a summary of the NBER recessions since the 1930s.

I averaged the contributions of net exports to real GDP growth for the Pre-crisis period, the Peak-Trough period, and the Post-Trough period. All the Pre- and Post- periods are 4 quarters except the most recent recession which I averaged from the Trough to the latest available quarter.

The graph presents the results of that procedure and confirms what a more detailed examination of the data reveals. The US economy has not recovered from recessions since 1947 on the back of net exports.

Even when there are some positive contributions demonstrated the real exchange rate was appreciating!

A more detailed analysis also shows that there hasn’t been one recession recovery that has succeeded when austerity was imposed as the economy peaked and moved to trough. Fiscal policy has tended to support growth during recessions and given way to a rebound in private spending (consumption and investment) as the economy recovers.

It is false to claim otherwise.

The other point that I make in this blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – is that the only times on record where a nation has successfully grown out of a recession by imposing fiscal austerity and relying on net exports for the spending impulse – were at a time when the major trading partners of the nation were growing strongly and the recession experience of the nation was singular.

There is no case available where fiscal austerity has led to growth via net exports at a time when austerity is also being broadly imposed on the nation’s trading partners and there is a global recession.

Conclusion

Once again we are confronted with the conservative denial of the obvious – that public or private spending engenders growth.

If monetary policy is ineffective because no-one wants to borrow at the lower interest rates because they are deleveraging and rebalancing their spending patterns (downward), then there is a need for fiscal policy to provide spending into the economy directly.

Relying on net exports to drive growth at a time when a government is cutting spending and the private sector is tightening its spending and all other nations are following the same plan is doomed to failure.

Further, it is clearly false to say that all nations could drive its growth via net exports. For one nation to be enjoying a spending boost from net exports (external surplus) there has to be at least one other nation experiencing a drain on domestic spending arising from net exports (external deficit).

As a general rule, growth is driven by domestic demand.

I wonder if Ms Schlaes and the economists she chooses to publicise would agree to put their jobs and wealth on line – perhaps negatively indexed to changes in the unemployment rate and its duration above certain levels – and still advocate pro-cyclical fiscal austerity.

You can bet they would not!

Alternative Olympic Games Medal Tally

My Alternative Olympic Games Medal Tally continues.

I update it early in the day and again around lunchtime when all the sports are concluded for the day.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

There are many interesting points here, but I think it is just a waste of time wasting time on people like Amity Shlaes. Proving they are wrong won’t affect them. Ignoring them might.

“The more sophisticated understanding of quantitative easing is that it impacts on the economy by reducing long-term interest rates”

I’ve just re-read QE 101 and there is nothing on there about the other mechanism the ‘true believers’ are now starting to tout – the idea that QE injects by essentially overpaying for the assets.

That then leads to the next approach which is to get the central bank to deliberately overpay for these assets.

So you take a government bond priced at, say, $100 and buy it for, say, $1000. That gives the seller $900 more than they were expecting for the bond, which they then spend. World saved – allegedly.

There is less spoken about the flip-side, which is that people in the market to buy these things suddenly need 10 times more savings to buy them. What will they do instead?

So the narrative is moving away from lending and reducing the interest rate on bonds and more towards the fiscal injection from overpaying for assets (which I presume they think will move money from ‘savers’ to ‘spenders’).

It all strikes me as a fiscal operation, which begs the question: Who decided ex-bond holders are the most appropriate people who should receive government spending stimulus?

Good article except for the opening line. As far as I can tell, Austrians are anything but economic conservatives. Are there any Austrians arguing for austerity? I’m yet to see one. As far as I can tell they agree with a lot of what MMT says but diverge on MMT’s political ideology as clearly they do not embrace government. Does that sound correct? Maybe I am exaggerating.

Esp Ghia,

I think Bill is right. Austrians are conservative in the sense that they favour doing nothing about the recession, which is what Bill meant presumably. On the other hand they are not conservative in the sense that their ideas are unconventional.

You ask, “Are there any Austrians arguing for austerity?” I’d say “yes”. For example the “Cobden Centre” is Austrian. Google Cobden Centre and “print money”, or something like that, and you’ll find loads of articles on that site which virulently oppose any sort of stimulus or money creation as a way out of a recession.

Thanks Ralph Musgrave. I scanned one article there about Europe and the author was opposed to the tax increases that were being implemented. Regards.

Neil, good comment. However, QE targets rates, regardless. That’s the stimulus, and being in cash is the investor preference transmission mechanism. You know this, you cannot target rates without affecting price. It’s the nature of the beast that makes monetary policy work. The Fed forces no one to sell, they just agree to do so at those prices ad low yields. And at those prices, in this environment, it about a return “of” capital, as much as possible, unfortunately.

But to take a stab at answering your concern, banks should have sufficient reserves (due to the over priced purchases) to reverse the repo trade as rates begin to rise. Well, that’s how the Fed will raise rates, anyway, pulling those excessive reserves from the system. Otherwise, they can always borrow at the discount window to cover their reserve requirement of their remaining assets. Maybe a private investor would hold off and buy at lower – more normal prices to reap the higher yield.

Well there is real resourse constraints as a result of the very same neoliberal ideology pursued with vigour these past 30+ years.

Therefore the quality of fiscal stimulus is as important as the quanity , indeed more so as we enter deeper withen this entropy hole.

Ireland ( the poster child for neoliberalism) has very little core internal capital remaining – it has functioned especially since 1987 as a juristiction where capital flows through rather then stays and builds.

Therefore any undirected fiscal stimulus will function to increase hard money exports and energy oil & nat gas imports)

Most of its recent productive investment went into roads which carry hyper inflated bank products (cars)…..i.e. the “productive investment” orbited the bank credit hyperinflation rather then become a real driver for internal wealth generation.

Fiscal Investments must be directed as far from Bank credit as its possible to be.

Unfortunetly goverments have effectivally given up owning or operating utilties such as Power generation….which means any fiscal stimulus may find its way eventually to the Cayman islands.

In the Latest HM treasury paper on infrastructure(nov 2011) it breaks down investment in these areas…… energy generation is now 100% privately financed……these privately owned utilties function and make profits by simply running down former state assets……at the most they invest in a few Gas turbines which have a very low upfront capital cost but high running cost which they externalise on the wider population to express company profits.

This explains the failure of Nuclear energy in a neo -liberal world – the up front capital costs are enormous but nothing I repeat nothing else around now has the energy density of fission – its physical capacity to overturn the disastrous post 1990 dash for gas policey is obvious but it cannot do so under the present ideological cage as it needs money spent into existence rather then wait for a return.

The return is infact to the wider society as enormous amounts of highly valuable Nat Gas is released for direct combustion elsewhere rather then be used wastefully on electrical generation.

Neil Wilson asks, “Who decided ex-bond holders are the most appropriate people who should receive government spending stimulus?”

I think part of the answer is that the elites always look after their own. Central bank officials, senior politicians and holders of large chunks of government debt mix socially and as part of their jobs or professional duties. (Incidentally I’m referring to DIRECT holders of debt AND pension fund managers etc: i.e. those responsible for looking after large chunks of government debt for others.)

Adam Smith spelled out very clearly what happens in the above scenario: “People of the same trade seldom meet together . . . but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public..”

If you’re a senior politician or central bank official and you have the choice between keeping those you regularly meet happy, and in contrast keeping those dreadful inhabitants of Main Street happy, well it’s a no brainer.

And – the arguments reduces to a rather crude expression of their dislike of government activity. Professor Bill Mitchell

True so why not flank that dislike? Government money does NOT require government activity! Just give the population money! How many people sent back GW Bush’s stimulus checks? Heck, I even spent Obama’s too!

Steve Keen’s universal bailout (which he calls “A Modern Debt Jubilee”) would give the entire population, including non-debtors, equal amounts of new fiat. What’s wrong with that? Price inflation risk? Then place corresponding credit creation limits on the banks. Ideally, the banks should not be allowed to create ANY credit so that would open a VAST deflationary hole for government to fill with new fiat as existing credit debt was paid off with no new credit debt to replace it.

It’s only government MONEY that is needed; the whole size and scope of government argument is mute.

On the other hand they are not conservative in the sense that their ideas are unconventional. RM

Oh come on. Most Austrians are for a gold standard. Their ideas are unconventional only because they are old and reactionary,

Google Cobden Centre and “print money”, or something like that, and you’ll find loads of articles on that site which virulently oppose any sort of stimulus or money creation as a way out of a recession. RM

Ah yes, the “malinvestments must be purged.” Does that mean that everything built during the boom and every job created should be purged too? Or that those which survive a “purge” are by definition not malinvestments while those that don’t are? Is that why housing must rot while people go homeless?

It is my understanding that the Fed contols short term interest rates by paying the banks for their excess reserve balances and that short term rates influence the entire rate structure :why then is it necessary to use QE to reduce long term rates ?

:why then is it necessary to use QE to reduce long term rates ? JB

To recapitalize banks on the sly? And provide the US Treasury with low cost financing?

1) Fed buys US Treasuries from the banks. Fed pays whatever it takes to finance US deficit?

2) Banks buy new US Treasuries at primary dealer auction with proceeds? Banks aren’t too concerned about low yields since they can resell to the Fed anyway?

3) Go to 1

Banking is truly a filthy business. It’s really sad that so many think it is necessary.

Bill, what about the effects of the carry trade? Aren’t banks depreciating currencies by taking the QE money and investing it overseas?

@JB

It can take considerable time for the structure to change course and drive down long-term rates. QE was equivalent to hitting the fast-forward button on the process by targeting those rates directly.

@Aiden

The reserves from QE don’t actually increase the banks’ capacity to make loans. Leverage caps and capital requirements are the real limiting factors for the carry trade in the fx market.

Bill, have you seen this: \”Modern Monetary Science\” explained to Congress in 1939, although it was sent to the Government Printing Office January 24, 1939, which means it wouldn\’t have appeared for another two months, seven months before WWII broke out. So who read it?

Richard L Owen, Former Chairman, Committee on Banking and Currency, United States Senate:

National Economy and the Banking System of the United States – An Exposition

of the Principles of Modern Monetary Science in Their Relation to the National

Economy and the Banking System of the United States

76th Congress, 1st Session, Senate Document 23, Sent to Government Printing Office, January 24, 1939

http://archive.org/details/NationalEconomyAndTheBankingSystemOfTheUnitedStates

It appears to me to be a document that explains to Congress (and what he calls \”students\”) the wisdom of going off the gold standard domestically in 1934, and he sneers at those who think the gold standard should return.

The author\’s tables disputes Ms. Shlaes\’ figures. He makes a passionate case to increase the money supply for the full employment benefit of the bottom half of society (actually 82%). He makes a lot of points that MMT does.

Hi!

I’m from Sweden and I’ve been following this blog for a few months now. Though I don’t

understand many of the things you guys are talking about (I’m a computer tech, not a

economist) I am getting the impression that you guys might be on the right track.

One thing I know for certain, the economic mobilization to fight WW2 eliminated

unemployment in the USA and other countries. If it is possible to spend mountains

of resources and oceans of oil building precision machinery (tanks, aircraft, even

shells & bombs) in order to kill vast numbers of humans and destroy huge amounts

of property (a massive waste by any means), then why can’t these same methods

be used for something useful in peace time?

To me, WW2 is proof that unemployment can be eliminated if only the will exists.

The question then is not; is full employment possible? Because it obviously is. Nor is it;

should it be done? The amount of human misery inherent in large scale unemployment

is intolerable to anyone with a sense of empathy for his fellow man. The question

is rather; why hasn’t this already been done? The answer; it has.

Foundations, Decline and Future Prospects of the Swedish Welfare Model: From the 1950s to the 1990s and Beyond

http://lilt.ilstu.edu/critique/spring2002docs/jcoronel.htm

Makes for interesting reading. I can’t vouch for it’s accuracy because I’m not a expert

but from what I know of my country’s history it contains nothing obviously wrong.

If the content of that paper is accurate (I haven’t been able to find unemployment

data online from before 1985), then Sweden had a unemployment rate of under 2 percent

for over twenty years. 2 percent! That can’t be a fluke. It spans way too much time. It was

obviously a man made system and it worked for many years.

I hope I have contributed with something of use.

Thank you for your time!