The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Oh Ireland, if only you were growing

I regularly check the data for Ireland to see how she is going, given that the Irish government was the first to impose the austerity solution in early 2009 – that is, three years ago. I read yesterday that “of the countries that were in trouble, I would say Ireland looks as if it’s the best at the moment because Ireland has implemented very heavy austerity programs, but is now beginning to grow again”. That created some cognitive dissonance for me. Was I dreaming when I last looked at the Irish national accounts data? Surely, I hadn’t made a mistake when I concluded that the last two quarters of 2011 recorded negative growth as Irish exports slowed in the wake of the emerging double-dip recession in Britian? When I reviewed the data today, it seems that Ireland is still going backwards and people are becoming poorer. Claims that Ireland’s austerity approach provides a model for other nations to follow because it produces growth cannot be sustained from the data. But if only it were true … Oh Ireland, if only you were growing.

Ireland – the model

That comment came from an interview on the US NPR (April 30, 2012) – Austerity Measures Cost Some Politicians Their Jobs – with one John Peet, who is the Europe Editor of The Economist Magazine.

The topic of the segment was the “backlash against austerity measures” in Europe and he was asked whether there was “anybody offering any alternatives to massive budget cuts and tax increases”. He replied:

There is a lot of feeling out there that given how many economies are in a recession, more cutting of budgets and possibly more tax increases might not be the right answer. But there is very little by way of alternative because those who say we need to have more growth-promoting policies are not actually saying, you know, let’s start spending more money because they realize that the financial markets would react if we went back in that direction. So it’s all fairly vague stuff.

No it isn’t “fairly vague” at all. It is in fact quite clear what is needed – more aggregate demand. Here are some specific policies that would immediately stimulate growth within the current Eurozone structure.

The EMU national governments could immediately announce a Job Guarantee – a socially-acceptable minimum wage job offer to anybody who would desire to work.

Then they could announce several major public infrastructure and environmental infrastructure initiatives (after due consideration), and before they did that and just after they announced the Job Guarantee they could announce a means-tested cash handout of some amount to all citizens.

The ECB would announce that they were backing the measures fully – and would work within current EMU rules to ensure that happened (so the JG wages could start flowing immediately).

The EU would announce that the ECB would fund a free holiday for 2 weeks for anyone who has been unemployed for longer than three months and their families to various locations – the destinations would be selected according to the scale of the loss of per capita income in that nation since 2008. The ECB would see the funds were allocated.

The member states would also announce that they were purchasing all properties currently in foreclosure (at the prevailing market prices at the time of the announcement) and would then offer the defaulting occupying mortgagees the opportunity to rent their houses/apartments back for 5 years with the option to purchase them back again after that period at the prevailing market prices with all rents paid in the meantime being written off the principle. The ECB would see the funds were allocated for this venture.

The financial markets would have no influence on any of this given the ECB was funding the entire operation via the national central banks.

Once growth resumed the EU elites would then have time to plan an orderly break-up of the monetary system and return currency sovereignty to the democratic states who would then float their currencies.

When someone invokes the TINA option when it comes to economic policy you know they either have no imagination, no understanding or are wilfully intent on maintaining some ideological position that precludes alternatives.

John Peet was then asked where there are “any economists out there who say you could do something different within the parameters that the bond market is going to set”. He replied:

Well, I think the professional economists, what they want to see is much faster implementation of reforms to the labor market, deregulation, liberalization of product markets across Europe to make the European economies more competitive.

The mainstream economists certainly want these things and that is exactly why they should be disregarded. The fact that their prescriptions were followed previously by various governments is the reason the World is in such a mess as is noted in the quote.

When I present the demand-side imperative, I don’t want it thought that I ignore the “structural” or supply-side of the issue. There are clearly some supply-side issues that have to be addressed – for example, appropriate taxation increases and regulative impositions for polluting firms; much fuirmer regulation for the financial sector (including outlawing many of the current practices and products); increased aid to those in poverty; and more equitable pensions and tax structures.

But these issues, while important in improving the efficiency of the economy are not the current cause of the stagnation. The current problem is lack of aggregate demand (spending). That has to be addressed first.

It is also the case that structural changes are easier to accomplish (given they always involve pain to some) when there is growth.

John Peet was then asked whether the “German debate on austerity … [was] … shifting at all”, and he replied:

Very little. I mean, one of the problems with this debate is that those who are against too much austerity are also demanding that Germany should do more to expand the economy to push growth across Europe. And a perfectly understandable German response to that is, look, we are doing better than we’ve done for 20 years already. Why should we, you know, do anymore?

It is a totally misguided German response. The penny doesn’t seem to have dropped that the “German model” of suppressing domestic spending growth (via harsh real wages suppression) and relying on export markets to drive growth overall is unsustainable when the fellow Eurozone countries buy the majority of its exports.

German growth was driven by the spending growth in other nations (aided by the credit binge) that they now criticise. With Germany refusing to stimulate domestic demand and gaining competitive advantage by suppressing local workers’ prosperity the external deficits now the focus of attention in other nations were inevitable.

Otherwise, the Eurozone would have entered recession earlier.

If the nations restored their own currencies, then the Deutschmark would appreciate significantly under current domestic policies (perhaps by around 30-40 per cent). This would increase German unemployment if the Government didn’t act to stimulate demand and firms continued to suppress real wages growth.

The other nations would see an improvement in their trading positions and domestic demand would increase.

But even within the fixed exchange rate system, the Germans could improve things by stimulating domestic demand. However, it seems that the nation is completely spellbound with austerity.

But the imposition of austerity across Europe is also undermining German growth. That was inevitable. Please read my blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – for more discussion on this point.

I noted a Bloomberg article yesterday (May 3, 2012) – German Majority Ready to Help Pay Down State’s Debts, Poll Shows – which reported the results of a public opinion poll indicating that:

… a majority of German voters said they are prepared to help the state pay down its debt … Fifty-nine percent of respondents said they were ready to accept personal sacrifices so that the federal government, the states and municipalities didn’t have to take out new debts …

Which tells us something about the German penchant for suffering.

Finally, John Peet was asked whether there was “any country that seems to be leading the way out of here” and after mentioning Poland and Sweden (both non-Euro nations) he said:

… And of the countries that were in trouble, I would say Ireland looks as if it’s the best at the moment because Ireland has implemented very heavy austerity programs, but is now beginning to grow again. So there are some examples …

Ireland – as a reality

Ireland? I last considered her in this blog – How’s poor old Ireland, and how does she stand? – when the third-quarter 2011 national accounts data came out. It wasn’t looking to be in good shape then.

I had also thought I noted similar trends in the most recent (December quarter 2011) – National Accounts – data for Ireland issued on March 22, 2012 by Ireland’s Central Statistics Office.

So I went back to the data.

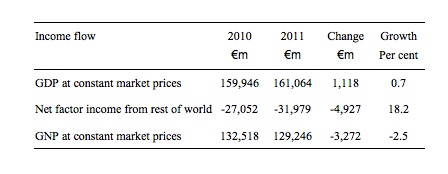

The CSO opened with the headline – Annual increase of 0.7% in GDP in 2011

Which is the figure the proponents of austerity like Mr Peet are clearly hanging their case on. The real GDP growth of 0.7 per cent in 2011 favourably compares to the contraction of -0.4 per cent in 2010.. So, in that respect the economy did grow a bit in 2011.

But if you dig more deeply you will see a different picture. First, you will realise that the Irish economy contracted over the last two quarters of 2011 as its exports performance contracted. This gives you an idea of where things are heading rather than using the annual result for 2011.

Second, you will realise that for the local residents in Ireland things got worse not better over the course of 2011 and all the growth and then some was expropriated by foreigners.

The Irish data does not provide a compelling case for austerity. This is not a model for other Eurozone nations to follow. In fact, it is likely that the main driver of growth (exports) in Ireland will stall badly in coming quarters given the fact that the UK economy has now recorded a double-dip recession.

The CSO said in their most recent National Accounts release that:

On a seasonally adjusted basis, constant price GDP for the fourth quarter of 2011 decreased by 0.2 per cent compared with the previous quarter while GNP declined by 2.2 per cent over the same period.

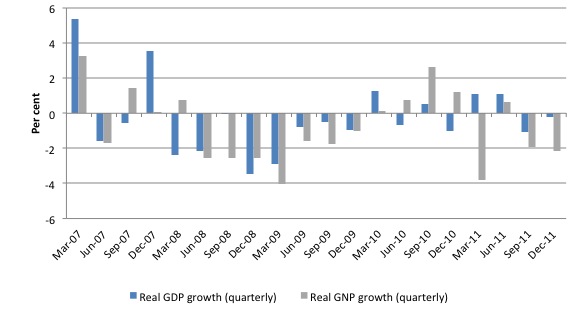

The following graph shows quarterly growth rates in real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Gross National Product (GNP) from the first quarter 2007 to the December 2011 quarter. The last two quarters for 2011 shows a real GDP declined by -1.1 per cent in the September quarter and by 0.2 per cent in the December quarter. Real GNP declined by 1.9 per cent in the September quarter and 2.2 per cent in the December quarter.

That is not a model of growth for anyone to follow.

First, you need to first understand the difference between GDP and GNP. This is a particularly important point when it comes to understanding the Irish predicament (both before the crisis and now.

You can gain a thorough understanding of these concepts from this excellent publication from the Australian Bureau of Statistics – Australian National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods, 2000

The two concepts are defined as such:

- Gross domestic product (GDP) is defined as the market value of all final goods and services produced in a country in any given period”.

- Gross National Product (GNP) is defined as the market value of all goods and services produced in any given period by labour and property supplied by the residents of a country.

The Irish CSO publication says that GNP = GDP + Net factor income from the rest of the world (NFI). NFI is defined as:

Net factor income from the rest of the world (NFI) is the difference between investment income (interest, profits etc.,) and labour income earned abroad by Irish resident persons and companies (inflows) and similar incomes earned in Ireland by non-residents (outflows). The data are taken from the Balance of Payments statistics. However the components of interest flows involving banks in this item in the national accounts are constructed on the basis of “pure” interest rates (that is exclusive of FISIM) whereas in the balance of payments the FISIM adjustment is not carried out. There is an equal and opposite adjustment then made to the imports and exports of services in the national accounts which is not made to these items in the balance of payments. The deflator used to generate the constant price figures is based on the implied quarterly price index for the exports of goods and services. In some years exceptional income payments have had to be deflated individually.

In this blog – The sick Celtic Tiger getting sicker – I argued that the so-called “Celtic Tiger” growth miracle was an illusion and was driven by major US corporations evading US tax liabilities by exploiting massive tax breaks supplied to them by the Irish government.

In a New York Times article (May 20, 2010) – Irish Miracle – or Mirage? – by Peter Boone and Simon Johnson, we read that:

… 20 percent of Irish gross domestic product is actually “profit transfers” that raise little tax for Ireland and are owned by foreign companies – the Irish miracle was a mirage driven by clever use of tax-haven rules and a huge credit boom that permitted real estate prices and construction to grow quickly before declining ever more rapidly. The biggest banks grew to have assets twice the size of official G.D.P. when they essentially failed in 2008.

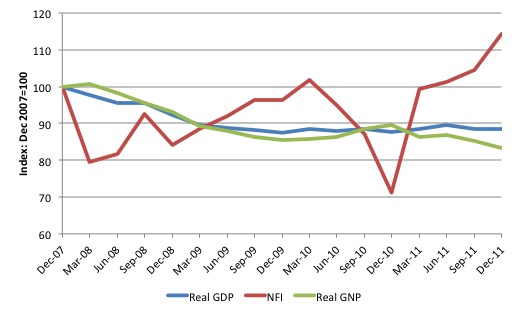

I indexed the national aggregates (GDP, GNP and NFI) at 100 at the GDP peak of the last cycle (December quarter 2007). As at the December 2011 quarter, the GDP index was 88.4, the GNP index was 83.3 and the NFI index was at 114.3.

The following graph shows the evolution of these indexes between December quarter 2007 and the December quarter 2011. It is not a model economy.

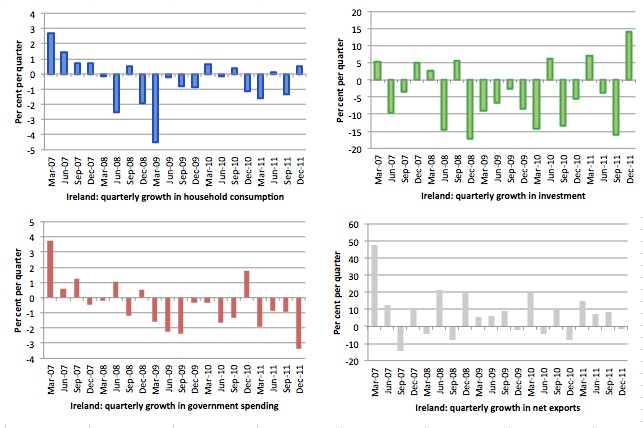

The following graph shows the quarterly growth in the major spending aggregates since the downturn took hold in Ireland (March quarter 2007). Personal consumption growth remains subdued, while government spending growth is aggressively negative and the short-boost from exports growth is now over. Only private investment (capital formation) showed any reasonable growth in the December quarter but that has been very volatile over the period shown. With the main driver of growth (exports) now in retreat it is hard to see any sustained investment boom happening in Ireland in the coming year.

The following Table puts the annual figures into perspective. While real GDP did grow by 0.7 per cent over 2011 (even though it is now declining again), real GNP contracted by 2.5 per cent over the same period. Net factor income to foreigners grew by a staggering 18.2 per cent over 2011.

The data puts the “trade recovery” into perspective. The growth over 2011 came from exports (which is signalled by the GDP figure). However, the domestic economy continued to decline and unemployment rose further (as indicated by the GNP figure).

By excluding the expatriated profits of foreign multinationals, GNP provides a better picture of how the domestic economy is delivering welfare improvements to its residents. The fact is that Ireland continues to go backwards in this regard.

As its major trading partners are implementing austerity and going backwards, GNP has shrunk sharply in the latter half of 2011.

So Ireland’s growth strategy has been based on increasing exports of real goods and services which are a cost to the domestic economy (forgoing local use). Further, any growth dividend is being being expatriated to foreigners as rising income.

The only conclusion you can draw at this stage is that the austerity package is further impoverishing the local residents and handing over increasing quantities of Ireland’s real resources to the benefit of foreigners. That doesn’t sound like a very attractive option to me.

In March 2005, the OECD Observer said this:

Ireland is another country where GDP has to be read with care. Ireland’s position has risen up the GDP per head rankings since 1999, and is now in the top five countries in the OECD … But does GDP per head accurately reflects Ireland’s actual wealth, since all that inward investment (and foreign labour) generates profits and other revenues, some of which inevitably flows back to the countries of origin?

Another measure, Gross National Income, accounts for these flows in and out of the country. For many countries, the flows tend to balance out, leaving little difference between GDP and GNI. But not so for Ireland, as outflows of profits and income, largely from global business giants located there, often exceed income flows back into the country. This means that in a GNI ranking, rather than being in the top five, Ireland drops to 17th. In other words, while Ireland produces a lot of income per inhabitant, GNI shows that less of it stays in the country than GDP might suggest.

The reality is that the few quarters of positive GDP growth that Ireland experienced before heading back into negative growth did not impact positively on the labour market – which presumably matters more than whether the economy is producing net income for foreigners.

Conclusion

In this blog from July 2010 – The Celtic Tiger is not a good example – I noted that Ireland’s growth was coming from the modest growth in the US economy. As the Euro depreciated against the US dollar, Ireland’s exports (pharmaceuticals, software, food and services) became increasingly cheaper and more attractive to its two major trading partners Britain and the US.

Exports were driving Ireland’s growth. I noted then that with the UK economy heading back into recession courtesy of its own government’s austerity mania, that the Irish recovery would soon come to an end.

That prediction has been validated by the data.

Austerity begets austerity and trade is one way that the transmission occurs.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back tomorrow. No predictions are being given about the ratio of True to False answers. Like financial ratios such as the deficit to GDP and public debt to GDP ratios, that would be a meaningless statistic.

That is enough for today!

It is a totally misguided German response. The penny doesn’t seem to have dropped that the “German model” of suppressing domestic spending growth (via harsh real wages suppression) and relying on export markets to drive growth overall is unsustainable when the fellow Eurozone countries buy the majority of its exports.

There is no God-given law that only Eurozone countries have to buy the German export goods. In fact, it is not even true that the majority (in the strictest sense of the word) of the German exports go into Eurozone countries – in 2011, the Eurozone countries only made up 39.7% (i.e. only a plurality) of the German exports, whereas the non-Euro exports made up 19.5%, Asia 15.8% and the Americas 10.4%.

As the crisis affected the Eurozone countries, their proportional part in German exports sunk (altough even the exports to those countries still grew in absolute terms!). Overall the German exports recovered sharply in 2010 and 2011, so it is obvious that other regions of the world took up the slack and compensated – both Asia (especially China) and the Americas helped keep a very healthy overall growth. And that’s the thing you for some reason seem to keep missing in your analysis of German policy: the reforms Germany undertook in the last half a decade were not primarily in order to be competitive just within the Eurozone – the main goal was to be competitive globally. Since there is still a huge growth potential in the emerging markets, the “German model” is quite sustainable for the forseable future, at least as long as German goods remain competitive in terms of quality, technology and of course costs.

Now, of course, the rest of the world can’t compensate the Eurozone entirely, Germany’s well-being is undeniably dependant on the well-being of their main trade partner, which is the reason Germany is financing so much of the various rescue packages being implemented. But there is enough demand for German goods in the rest of the EU and the rest of the world that even a longer (mild) recession within the Eurozone would not necessarily have major negative effects.

Also, the German reforms did have as a result a stronger domestic demand – both 2010 and 2011 showed clear gains in terms of private consumption, in fact the domestic demand played a major role in the growth in the last year. While actual real wage growth in this period was not particularly high, the comparatively strong growth in employment numbers (and reduction in unemployment) provided nonetheless more spendable income. And altough the growth has cooled down at the end of 2011/beginning of 2012 and as a result the employment numbers will probably no longer grow as fast as they did, there is plenty of reason to think that the domestic demand will remain strong even in 2012 – both the current tarrif negotiations in several important economic branches and the more-or-less agreement in the politic on the need for a form of minimum wage rules tend to suggest that the real wages will grow, probably even more sharply than they did in the last two years. Which is exactly what other Eurozone partners are asking of Germany.

Dear Bill, once again a great comment! I totally agree with you on every single point. Your blog is really indispensible for anyone who is interested in real economic problems and who is not content with the fantasy world of mainstream economics that we get served every day! I hope to read more of these well-written comments!

Bill,

Latest figures for EZ today show more contraction for Spain, Italy and possibly even France (election jitters over Hollande?) . More bad news to come before it gets better?

Look to total domestic demand at current prices for a even more dramatic picture

Y2007 Q4 : 45,268 million

Q2011 Q4 : 29,464 million

I agree with you regarding the issuing of Fiat but Irish economy is very open with a extreme oil import dependence as a result of the credit hyper inflated envoirment built up since 1987.

Issue 10,000 Euros or whatever to each account but also tax home heating oil to road diesel levels , cars etc.

We reduced our energy imports by 1 MTOE in 2011 according to provisional energy balance figures but despite this recorded record money exports / oil imports / energy imports…….

Our oil use is now at 1998 levels but there is a dramatic stock and flow problem as a result of the 1.8 million cars on the road etc etc.

Its a Disaster movie really.

Bill,

Thanks for your update today on our country!

Sorry I was reading some old national accounts from Q3

It should read

2011 Q4 : 30,781 (non seasonally adjusted) (think Christmas)

Sesonally adjusted it is in the sub 30 billion range at 29,891 million.

Bill should enjoy this:

Dean Baker in Al Jazeera English

Britain ‘does’ austerity so the US doesn’t have to

The country’s experiment in austerity has provided the US with valuable information: it doesn’t work.

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/05/20125142044487975.html

@ Andrei:

Sure unemployment has fallen in Germany…. by creating a massive amount of macjobs. I don’t count the destroying of secure, well paying jobs in favour of flexible no security temporary jobs, a recipe for economic succes. Blue collar workers are forced to compete with low cost east europeans, wages are slashed and there’s always the looming threat of Harz IV to keep workers in line. Sure, life may be fine and rosy for the middle class, as long as they’re being propped up by a ‘lumpenproletariat’ (for the record I’m no Marxist).

To add what Richard’s comments about Germany is that while the much vaunted Hartz reforms may well kept German costs in check and made their workers more productive it didn’t produce growth — most of the 2000’s when these reforms were being implemented were some of the worst years ever in terms of growth in Germany. Growth only returned with the economic crisis because first the German government spent and then so did others — the Chinese spent massive amounts of money during the economic crisis to stimulate demand as did the US as well, though not to the same degree. Now we have growth slowing across the globe, not just Europe, but in the US growth is slowing as it is in China as well, which will clearly have an impact on German exports. The point is the Hartz reforms haven’t caused German growth — though they’ve undoubtedly benefitted their companies bottom lines in terms of profits, but that growth came through others spending to stimulate demand, and demand is ultimately what creates growth — there’s no way around that.

Richard:

There were undoubtedly cases where companies exploited the various loopholes and defects of the original Agenda 2010 reforms in order to outsource their real need for fulltime labour into contractor, part-time or mini-job constructs.

But the impression that these alternative forms of employment destroyed full-time jobs on a large scale is not really supported by facts. Every statistic where full-time jobs are listed shows a clear trend of increased full-time jobs after the 2003-2005 reform implementation period. Granted, the definitions of full-time employment are a bit byzantine, and there are various tricks used in the employment and unemployment statistics in order to massage the numbers in the way the government wants them to be masssaged, but one of the simplest and clearest indicators of how many full-time full-salary jobs there are can be found in the statistics about the employees that have to pay social security taxes, the so-called Sozialversicherungspflichtig Beschäftigte – that excludes state functionaries, mini-jobbers and freelancers.

As you see, both statistics clearly show an increase even in the traditional, full-time jobs, and the inflexion point is very clearly the 2003-2005 period in which the Agenda 2010 reforms were implemented. After 2005, there is a trend of continual increase, and lest we forget, this continual increase in total jobs happens even in the face of a declining overall population.

So, there is plenty to criticise about the original reforms, and plenty of things that have yet to be addressed, like the loopholes on contractors or the lack of an economy-wide minimum wage regulation and a more logical progression in taxation between the 400 Euro mini-jobs and the normal jobs, without artifical barriers where you work more only to receive less because you now fall in a different category and have to pay social security contributions.

I hope the above-mentioned things will be changed asap, but overall, I fail to see how anybody can call the results of the Agenda 2010 reforms as anything less than succesful – they stimulated the employment numbers (including full-time jobs) and they kept unemployment under control even through a serious crisis, at least so far.

Keith:

These claims are ahistorical – Germany had solid real GDP growth right after the 2003-2005 timeframe when the reforms were implemented – 2006 and 2007 were pretty spectacular, and 2010/2011 as well, with 2008 and 2009 being under the influence of the global financial crisis. In short, Germany began to grow at a good pace well before the global financial crisis, and right after the reforms were implemented – I don’t want to claim that the Agenda 2010 reforms were the only reason for the return to employment and growth, because as always real-world economics are more complicated than simple input/output scenarios, but I fail to see any significant statistical data that shows they caused damage.

Andrei wrote:

“…in 2011, the Eurozone countries only made up 39.7% (i.e. only a plurality) of German exports, whereas the non-Euro exports made up 19.5%, Asia 15.8% and the Americas 10.4%.”

This does not add up to 100%. Where did the rest go ?

Also, please note that Germany’s exports to other European countries, per your data, amount to almost 60% of its total exports. It’d be fair to say that no European country can stay unaffected by the Eurozone crisis, whether that country is in it or not. So, the point about the “German model” being vulnerable to the Eurozone crisis remains valid.

Cheers.

Vassilis:

“…in 2011, the Eurozone countries only made up 39.7% (i.e. only a plurality) of German exports, whereas the non-Euro exports made up 19.5%, Asia 15.8% and the Americas 10.4%.”

This does not add up to 100%. Where did the rest go ?

I already provided a link to the source data, but if it really is that important, there is also the non-EU European countries, Africa and Australia/Oceania. So, it was:

Europa: 70,9%

Eurozone: 39,7%

Andrei, sorry for the typo. The correct sentence should read: Exports to all European countries (rather than “to other European countries”) amount to approximately 60% of all German exports, per your data, etc. Note that two thirds of German exports to Europe go to Eurozone countries, still per your data.

Cheers.

I’m sorry, the post slid out before it was ready. Here it goes again:

Vassilis:

I already provided a link to the source data, but if it really is that important, there is also the non-EU European countries, Africa and Australia/Oceania. So, it was:

Europa: 70,9% (out of which Eurozone EU: 39,7% & non-Eurozone EU: 19,5%)

Africa: 1,9%

Americas: 10,4%

Asia: 15,8%

Australia/Oceania: 0,9%

Which you will find totals almost 100%, with the rest being – altough not described in the PDF – usually the special regulation maritime trade (at least based on previous DeStatis statistics on foreign trade).

There have been several european countries (like Switzerland, Norway or Poland) which have stayed so far relatively unaffected by the Eurozone crisis (altough nobody really escaped the effects of the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009), so what is far to say is that stagnation or mild recession in a part of the Eurozone does not necessarily mean lack of growth in other parts of the Eurozone, the non-Euro EU, the non-EU Europe or of course the rest of the world.

Nobody says that a prolongued stagnation in large areas of the Eurozone or a very sharp recession would not affect Germany, in fact I explicitly said that even if the rest of the world would be in top shape, it probably still wouldn’t be able to compensate, but the point was that Germany does business with the entire world, so its economic model is designed with the competition on that stage in mind.