The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The sick Celtic Tiger getting sicker

All the recent Eurozone attention has been focused on Greece because they are the first EMU nation that the bond markets took an exception too although the other, immediately vulnerable southern nations are starting to feel the pinge. Meanwhile, Ireland, which along with the Baltic non-Euro states, were the first nations to implement harsh austerity programs (tax increases, public spending cuts), has stayed under the radar. The line I read often is that the Irish are more easy-going than the Latins and will accept the harshness with a smile. I wonder about that. But Ireland might soon be back on the main screen because despite all the IMF and EU predictions about the adjustment path that would accompany the austerity (things would get better relatively quickly), things have become worse. Just as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) would predict. And when you analyse the data in more detail, they are looking a lot worse than Greece. This also just exposes that the problem is the deficit and debt ratios but the fundamental design of the Euro system and the fiscal rules it forces onto member states.

In early 2009, Ireland introduced its harsh austerity program. The Prime Minister said at the time that a primary consideration was that Ireland had to address the crisis “in a way which would be seen to be credible by international markets”.

In April 2009, the Irish government forecasted “a decline in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of 7.7pc this year …[2009] … , and a contraction of 2.9pc next year before returning to growth of 2.7pc in 2011. It had originally projected GDP to shrink by 6.75pc this year” (Source)

The finance minister was quoted at the time as saying (Source):

If we fail, refuse or neglect to address this structural problem, we will condemn our generation and the next to the folly of excessive borrowing.

He was also quoted as saying that “without the measures, the public sector deficit would have stood at 12.75pc of GDP but is now projected to be 10.75pc of GDP both this year and next” and “adhere to eurozone rules on deficits by 2013”.

I read this article in the Irish Examiner (May 24, 2010) today – Cowen: We could have ended up like Greece and I wondered WTF!

The Irish Prime Minister Brian Cowen addressed the European Union Parliament and said that:

… the Government has been pursuing since July 2008 has been vindicated by recent events in Greece … Ireland has established “a degree of credibility” with budget measures that have already been taken … [had they taken the budget proposals of the opposition – less severe cuts] … we would be in a very severe crisis relying on supports that would effectively remove our economic sovereignty …

This statement should also be read in the context that Ireland is being asked to contribute Euros to fund the Greek bailout and in per capita terms their contribution will exceed that of Germany.

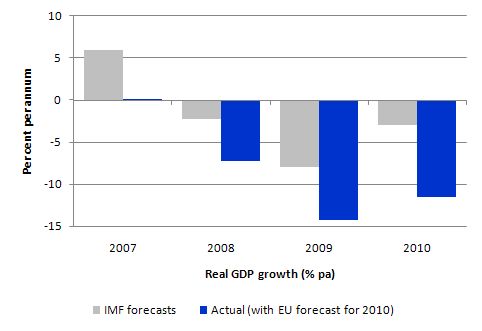

One of the problems is that the IMF and the EU consistently get their forecasts wrong and underestimate the extent of the recession. The following graph comes from the IMF World Economic Outlook for 2009. It shows the IMF forecasts for annual real GDP growth for Ireland (so 2009 and 2010 are estimated) (grey bars) and the actual national accounts results for 2009 (with 2010 being the most recent Eurostat forecast). So the later forecast is conditioned by the higher actual figure in 2009 (compared to the IMF forecast).

These forecasts also feed into their estimates of budget deficits (because they provide input into how significant the automatic stabilisers are going to be). In turn, the austerity packages are designed. So you can see how wrong the IMF was in early 2009 just as the Irish government was put their austerity policies into actions.

There are two ways of thinking about this – both of which might be applicable here. The recession was either much deeper than the IMF thought it would be (probably correct) and/or the austerity measures compounded the already depressed economy (certainly).

In that context, I thought this New York Times (May 20, 2010) article about Ireland – Irish Miracle – or Mirage? – was interesting. It was written by Peter Boone and Simon Johnson. I do not usually agree with their view of things although they are certainly measured in their rhetoric which makes them readable on an on-going basis.

Their basic hypothesis is that the PIIGS will not be able to make the adjustments that the EMU is demanding and by cutting “fiscal spending sharply … [to] … pull themselves out of this mess through austerity … some of these nations may be stuck in a downward debt spiral that makes greater economic decline ever more likely”.

This has been a point that I have been making regularly in relation to the calls for fiscal austerity in all nations. The calls seem to believe that the major cuts can be made in public spending at a time when private sector spending has collapsed and confidence is at an low and when foreign direct investment is weak and paralysed by uncertainty.

They also think that you can increase taxes (that is, reduce private demand further) and cut wages and hence private incomes and not expect major multiplier effects to make things significantly worse.

They also seem to have bought the IMF line that the fiscal multipliers are relatively low and that the automatic stabilisers (working to increase deficits as GDP falls) will not drown out the discretionary cuts in net spending arising from the austerity packages.

The overwhelming evidence is that this viewpoint is wrong and implementation of policies based on it cause generational damages in lost output, lost incomes, bankruptcy and lost employment (especially denying new entrants from the schooling system a robust start to their working life).

Boone and Johnson agree and argue that the current problems:

… are strikingly reminiscent of Latin America in the 1980s. Those nations borrowed too heavily in the 1970s (also, by the way, from big international banks) and then – in the face of tougher macroeconomic conditions in the United States – lost access to capital markets. For 10 years they were stuck with debt overhangs, just like the weak euro-zone countries, which made it virtually impossible to grow … Some Latin America countries lingered in limbo for a decade or more.

It is interesting to note that in political terms, this lost decade of economic growth ultimately has paved the way for a number of left-wing governments in South America, which have run against the tide of neo-liberalism in recent years and earned the scorn of conservative institutions like the IMF and the World Bank.

The interesting feature of the Boone and Johnson article is that they focus on Ireland and explain why the fiscal austerity program will fail. They say:

Ireland was one of the first nations to introduce tough fiscal austerity in this cycle – in spring 2009 the government slashed public-sector spending and raised taxes. Despite the cuts, the European Commission forecasts that Ireland will have one of the highest budget deficits in the world at 11.7 percent of gross domestic product in 2010. The problem is clear: when you cut spending you also lose tax revenues from people who earned incomes from that money. Further, the newly unemployed seek benefits, so Ireland’s spending cuts in one category are partly offset by more spending in another. Without growth, the budget deficit still looms large.

So the point is – fiscal adjustment comes with growth. The raison d’etre of fiscal policy is to support growth when private spending is undermining it and to constrain growth when private spending is supporting it.

The mainstream economists’ case against the use of fiscal policy as a counter-stabilising tool of policy activism was based largely on their claim that it tended to be pro-cyclical due to implementation lags (the time taken to actually get projects rolling and the funds flowing). Now, the mainstream exemplar of fiscal prudence is to enforce pro-cyclical policy positions. Go figure that one out!

Boone and Johnson offer this interesting insight to further their contention. They show how the growth miracle that led to the “Celtic Tiger” reference was in large part a mirage and driven by major US corporations evading US tax liabilities by exploiting massive tax breaks supplied to them by the Irish government. They conclude that”

… 20 percent of Irish gross domestic product is actually “profit transfers” that raise little tax for Ireland and are owned by foreign companies … the Irish miracle was a mirage driven by clever use of tax-haven rules and a huge credit boom that permitted real estate prices and construction to grow quickly before declining ever more rapidly. The biggest banks grew to have assets twice the size of official G.D.P. when they essentially failed in 2008.

The following graph is taken from the latest Irish National Accounts which cover up to the fourth quarter 2009. Flash estimates for the first quarter 2010 are available but not broken down like this.

The graph shows the difference between Gross Domestic Product (which counts all output produced) and Gross National Product (which exclude the profits of foreign residents) for Ireland. Once you make that correction, then you can see how much worse the domestic contraction has been in the Irish economy.

So GDP was 7.1 per cent lower than in 2008 while GNP was 11.3 per cent lower than in 2008.

Once you adjust for this (ignore these transfers) by using Gross National Product (GNP) which “excludes the profits of foreign residents” then Boone and Johnson conclude that the “budget deficit was about 17.9 percent of G.N.P. in 2009, and … will be roughly 14.6 percent in 2010 and 15.1 percent in 2011”. They say that “(t)hese numbers make Ireland look similarly troubled to Greece, with a much higher budget deficit but lower levels of public debt”.

And they say:

Ireland’s politicians, rather than facing up to their problems, are making things ever worse.

However, I part company with them when they argue that the Irish government has to persist with the “tough fiscal steps” and take advantage of the IMF and EU bailout funding to “bridge the tough journey of fiscal cuts ahead”.

From an MMT perspective, all this is doing is insulating the government from being 100 per cent exposed to the private bond markets. It doesn’t stop the demand drain arising from the austerity and the already weak private spending.

It will also not allow the government to reduce its deficit very quickly at all – indeed as we have witnessed the budget deficit gets worse and places further strains on the government funding crisis. This vicious circle can only eventually collapse in default (a la Argentina). The same goes for Greece.

The problem is that the Irish government has no real options while they remain constrained by the Maastricht Treaty and their lack of sovereignty. As noted above, while the Prime Minister might define economic sovereignty as the avoidance of default in a fixed exchange rate world this is far removed from what true currency sovereignty constitutes.

Boone and Johnson understand that too. They say:

… the Irish need to consider seriously whether being in the euro zone is worth the cost. The adjustment to this awful situation would be far easier outside the euro zone – even though leaving the zone might have adverse repercussions for other nations.

This is one of my regular themes when discussing the Euro problems. The design of the monetary system is incapable of delivering sustained prosperity and is crisis-prone when there is a major asymmetric aggregate demand shock experienced across the member nations. All the bailout packages and other add-ons will not change that.

Either they have to enter a fiscal union to support the monetary union or the nations should exit the system. Please see the blogs – Exiting the Euro? – Doomed from the start – Europe – bailout or exit? – for further discussion.

This message is consistent with the argument made in the UK Guardian by Mark Weisbrot in the article – Greece should look before it leaps – published May 18, 2010.

He argues that:

Greece might be better off leaving the euro and renegotiating its debt is considered by many to be unthinkable. Instead, the country is embarking upon a programme of “internal devaluation” – in which it keeps the euro and lowers its real exchange rate by creating enough unemployment to drive down the country’s wages and prices.

This is based on a comparison of what the IMF projected would happen as Latvia embarked on an internal devaluation in 2008 and what has actually happened. Weisbrot says that “when Latvia began … the IMF projected a 5% drop in GDP for 2009; it came in at more than 18%” The point being made is that things get much worse before they get better and that “Greece will probably need at least eight or nine years, if things go well under the current programme, to reach pre-crisis output”.

He then shows that in 1998, Argentina began internal devaluation” process – its currency was pegged at 1 to 1 to the dollar – until the end of 2001, leading to an economic and financial collapse”. After defaulting on the foreign-currency denominated debt and floating its currency, “the economy continued to shrink for just one quarter (first quarter 2002)” and “passed up its pre-crisis peak within three years of the default and devaluation.”

Right-wing Australian business commentator Alan Kohler also had his say about the EMU today in this article – Monetary union just doesn’t work.

He correctly notes that the “eurozone crisis goes much deeper than the sovereign debt problems of a few peripheral members” saying that the EMU situation has “two levels”:

1. Some countries have too much debt because they are poorly managed, and have been for decades, if not centuries, and one of them – Greece – has entirely run out of excuses and time.

2. Monetary Union doesn’t work.

The two things are actually unrelated, although they overlap and are being discussed together at the moment.

Now I don’t disagree with the two points but the problem with the first “level” (1) is because of (2) not independent of it. So the two things are totally related.

The only reason there is a sovereign debt crisis is because the nations within the EMU gave up their currency sovereignty. While bond markets might have pushed up the yields on public funding, if they had have remained sovereign they could have run a very loose monetary policy (keeping short-end rates low or zero) and the central bank could have also ensured long yields on public debt were low (by agreeing to buy whatever debt was issued at a fixed rate). Then if the private bond market didn’t want to buy at those rates the central bank would exhaust the buffer.

Of-course, they also could have simply stopped issuing debt altogether and gone on spending.

The obvious point is that a sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. The only danger of it using the spending capacity that comes with sovereignty (from a macroeconomic perspective) to underpin demand is that they will drive demand too hard. It is hard to see that happening given the output gaps that are in these economies at the moment.

Kohler shows he doesn’t understand this relationship between his “levels” 1 and 2, when he claims:

Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal would have to deal with their fiscal imbalances whether they were in the eurozone or not. Yes, they could devalue if they still had their own currencies, but that wouldn’t help their sovereign debt position – it would worsen it in fact.

The fact is that their sovereign debt position would be largely irrelevant and inversely driven by growth anyway. They could ensure that growth happens by maintaining strong fiscal support for aggregate demand.

As we noted above – growth is the only way to reliably reduce a budget deficit. This is because the public budget balance is largely endogenous to the business cycle. What does that mean? It means that given the in-built automatic stabilisers which work counter-cyclically a declining economy will always push the budget towards or into deficit and vice versa.

Moreover, the private sector spending (and hence saving) decisions are largely responsible for setting these automatic stabilisers into action. You will not get any significant reduction in budget positions in a time of contraction. And, if that contraction is exacerbated by pro-cyclical austerity policy then you not only worsen things but also damage the population unduly along the way.

So Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal (and Ireland) if they were not in the eurozone they would just have to focus fiscal policy on stimulating growth. But within the EMU they cannot do that because of the Stability and Growth Pact which imposes context-less fiscal rules on each member government.

Kohler is wrong about that. Outside of the EMU, these nations would be free – inside they are chained.

Where he gets it right is in his assessment of the viability of the monetary union. He says that:

The eurozone crisis goes much deeper than the sovereign debt problems of a few peripheral members. Mitterand and Kohl thought the treaty signed at Maastricht in 1992 and a single currency would inevitably lead to the United States of Europe and the dream of full integration and No More Wars.

They were wrong. Most of the nations of Europe were simply not ready, and not just because productivity in Greece, Spain and Portugal was not able to keep up with the Germans. The fact is none of the countries, especially Germany and France, were or are ready to give up their own identities, including their own independent national parliaments making their own laws and passing their own budgets.

So the problem is the flawed design of the monetary system and not deficits or public debt per se.

Total digression: something I was thinking about today

Here is former US cyclist (and Tour de France winner) Greg Lemond speaking at the weekend about Floyd Landis to a US sports channel at the weekend (Source)

I accepted his apology, but that isn’t really what’s important. Sincere apologies are for those that make them, not for those to whom they are made. I hope that as a result Floyd can begin rebuilding his life …

I also accepted his apology because his treatment of me challenged me to further confront my own issues and the pain that they were causing me. That challenge has made me a better, healthier, stronger person today than I might have otherwise been.

I don’t think I agree with this one-sidedness but I am thinking about it from another perspective.

Conclusion

That is enough for today!

“The obvious point is that a sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency”

That is also true of the EZ, albeit in a decentralized fashion.

“But within the EMU they cannot do that because of the Stability and Growth Pact which imposes context-less fiscal rules on each member government.”

The EZ operates in a fiat currency system. So this is no different than a constraint set by the US congress, and in fact no penalties were ever imposed for overshooting, whether that be France, Germany and more recently, quite dramatically, in Greece.

It is a political constraint, not an operational one, although the fragmentation of the EZ into independent central governments creates complications. I do note though that you give one line of credit to this line of thought by saying:

“Either they have to enter a fiscal union to support the monetary union or the nations should exit the system.”

Until that union a realized, cooperation between central governments, I suppose, could also be advocated.

“Outside of the EMU, these nations would be free – inside they are chained.”

But the EZ as a whole is not chained operationally, only by its political will.

If I applied a bit stubbornly your reasoning, I could say : well, since California suffers more say than Texas form the current deflation, they should secede from the US and issue their own currency. And I know you’ve actually hinted at that possibility, but not as goal that you actually consider advisable.

“if they had have remained sovereign they could have run a very loose monetary policy (keeping short-end rates low or zero) and the central bank could have also ensured long yields on public debt were low (by agreeing to buy whatever debt was issued at a fixed rate).”

The ECB is doing just that for Greek bonds. Of course, there are string attached, and it would be easier if it had only one market to supervise, not 12 (is it 16 now?). If congress decided to forbid that in the US, it would amount to the same. Again, a political constraint, not operational. Why the double standards?

“Of-course, they also could have simply stopped issuing debt altogether and gone on spending.”

Of course, but has it ever happened in the US? Again, double standards. There is a long ongoing debate going at WM (under Marshall’s latest) that MMT might be presenting its desire for the absence of self imposed constraints as reality.

Food for thought.

Having your sovereign currency with flexible exchange rates can be beneficial not only because of deficit spending effects that are not revenue constrained but also because of private production opportunity effects.

Let us assume production sectors in two countries producing the same good but with different efficiency. In the case of seperate currencies with a flexible exchange rate between them, they face a currency risk and in the case of a common currency they face no currency risk. In the case of seperate currencies, due to currency risk, comparative advantage implies diversification with production for both, altough more for the production sector with higher efficiency. In the case of common currency, comparative advantage implies a “corner solution” with all production undertaken by the more efficient sector.

Therefore, in the European situation, the Northern European producers with the higher efficiency will prefer a common currency and the Southern European producers of the same good will prefer seperate currencies. So who wins with a common currency area?

In the previous food for thought point, it is obvious that a similar effect comes from transportation costs.

Dear Bill,

All well but I thought you had modified your position about long rates in previous blog posts. I hope you realize that it is a mistake………..

Regards,

Takis

@ Bx12

Don’t you think that it is perhaps a bit of a stretch to equate a 230-year old political union to a decade of autonomous governments sharing a common currency-issuing function? That is like saying if you stretch a rubber band long enough, you can circumscribe the globe with it. Well maybe, but chances are the sucker is going to snap somewhere along the way, and everyone holding it at the time is going to get stung.

Dear Panayotis

Thanks for the comment. I actually haven’t modified my position at all. A central bank can clearly control the yields on primary issue public bonds by offering an elastic demand curve at a fixed yield at whatever maturity is relevant. For non-economists, an elastic demand curve just means it stands ready to buy all available issue. So if the yield is too low for the private bond dealers and they baulk at the issue then the central bank would take it all.

But what I have also said is that the central bank cannot control private bond yields and so a dislocation between the public and private yield curves may occur which would be of no real consequence anyway.

best wishes

bill

But Bill, assuming that you are not forced to buy up all the government bonds — in which case I would argue that the government, in selling something to itself, is not controlling the price — then you are making a very strange claim: that the risk-adjusted return of the “private” yield curve will differ from the riskless return of the “government” yield curve.

Can you provide a rationale as to why someone would be willing to buy a riskless asset for a price materially different from the risk-adjusted price? And if this were the case, wouldn’t there be arbitrage opportunities — e.g. free money — available up and until the risk-adjusted returns were equal to the risk-free returns? So I don’t see how such a state of affairs would permanently remain. People would make profits up and until the government was forced to buy all the debt. It might not happen in one day, for example, but it would happen, and fairly quickly.

Benedict@Large says:

Tuesday, May 25, 2010 at 9:49

@ Bx12 Don’t you think that it is perhaps a bit of a stretch to equate a 230-year old political union to a decade of autonomous governments sharing a common currency-issuing function?

The distinguish feature and strength of Modern Monetary Theory is an understanding of how a fiat currency system operates, whether it started 10 years ago or 230 years ago. Did you understand it any differently?

Bx12 @ 5:16,

Right.

The truth of course is that the US treasury is actually revenue constrained – due to the no overdraft rule.

The reports are that this constraint has been binding once in the last 100 years ago or so. At least those are the reports.

If that constraint were to become chronically binding at some future point, then Congress could change the law to allow regular treasury overdrafts at the Fed.

At that point, and only at that point, would the US treasury be truly free of its previous revenue constraint.

Taken to its limit, that contingency arrangement would become the MMT no bonds proposal.

Dear Bill,

I do not want to argue in your blog with you but I do not agree with you on this point. I refer to my comments in previous blogs on this issue including a math presentation of the several factors that influence long term rates. As you know, control theory demonstrates that is very complex and indeterminate to attempt to manage many dynamic factors influencing a market with only one instrument unless you are determined to buy all supply (as also RSJ points out) which means that the secondary market has become internalized and non existent! It is less costly and more optimal to buy directly from the Treasury.

As an example of real situations see what is happening with the ECB that is attempting to influence the secondary markets of European gobernment bonds with limited effect as my contacts at the bank are telling me. They are frustruated!

Dear Panayotis

That is exactly the purpose of the comments section. I am not god. I like people to argue with me and find errors.

But this is what I said:

Nothing at all about secondary markets. The only yield that matters is what price the government pays for its debt given that they insist on issuing it. It doesn’t matter what some bond speculator pays when buying from another bond speculator. That doesn’t influence the public budget at all – the government still pays the same coupon and the same face value on maturity irrespective.

Note also I said an elastic demand curve – that is, I agree with RSJ and you – the central might have to buy the lot. In which case they would get smart and cancel the auction tender system altogether and flip some credits into the Treasury bank account and add an asset to itself (the debt). And we would call it the government borrowing from itself and everybody would be happier.

So what the ECB is doing in secondary markets is missing the point I am making.

best wishes

bill

Panayotis,

“Having your sovereign currency with flexible exchange rates can be beneficial not only because of deficit spending effects that are not revenue constrained but also because of private production opportunity effects.”

Why wouldn’t deficits not be revenue constrained in say Germany, had they so chosen, and which they experienced to some degree BEFORE the monetary union?

In fiat a monetary system, such a constraint is self imposed. Who is going to disagree with this?

Why are the Germans revenue constrained AFTER the monetary union? Because the union imposes that, and they also chose to make things even harder on themselves, and by ricochet on the others, with a constitutional provision. These are institutional arrangements, i.e. self imposed constrained. Correct?

So there’s an implied premise in your sentence, if you allow me to say, that you maybe have to reconsider. I see what you are getting at with a two country model, but I can’t help much as I think too many variables come into play to get anywhere close to reality. However, I could add this:

Sure, you lose degrees of freedom by transition to a MU, namely the fx rates between the member states. But then the US does not have varying fx between different regions either. What the US has, though, is a centralized deficit spending initiator, the Federal government. That spending in EMU is decentralized, probably an enduring feature, and also uncoordinated. Coordination is on the table already. What does MMT has to recommend?

MMT claims no financial crisis cannot be overcome. How would the rules have to be rewriten, to free sufficient maneuvering space for the ECB and the governments to get onto a path of growth?

I hope Benedict@Large is reading this, because she will notice that I’m not equating US with EMU, as she has claimed. I think I’m a little more discerning than this.

Well, the prices in the primary auction are determined by the expected resale value in the secondary markets. Primary Dealers directly bid on the bonds, but only with the intention of reselling them. And actually all securities, if they are credit market instruments, are bought at price that would justify profitable re-sale.

So my point is to first decide if you are going to bother selling bonds at all, how many, and when. That’s a bit complicated, and I don’t have any clear stance — it would be really interesting to have a debate about this. I think such a debate would require a full proposal to completely restructure the financial system, since it currently requires a large supply of government debt in order to function.

But if you *do* decide to sell government bonds, then you must sell them at auction at fair market prices. That is the only way you can best prevent financial actors from earning arbitrage profits. Government should have a no-arbitrage policy in which it does not try to manipulate credit market yields under any condition.

As you say, nothing requires the government to participate in the credit markets at all. The government need only intervene in the real economy. But if it does participate, it the bonds should go the highest bidder in a free and open auction.

Dear Bill,

If the CB buys all the primary issue of LT debt (I am not arguing about the very short end of open market operations) then this becomes an internal government operation and is not a market. A secondary market is available for private holders to resell their holdings assuming they own any! In this scenario there is no need to issue public debt since as I have said in other comments it is more optimal for government to spend by directly crediting accounts.

” anon says:

Tuesday, May 25, 2010 at 10:45

Bx12 @ 5:16,

Right.

The truth of course is that the US treasury is actually revenue constrained – due to the no overdraft rule.”

And before that, by what congress actually deems appropriate as a deficit level? The only difference with the SGP is that one is revised and sometimes every year (Congress), whereas the latter, is written in the Maastricht, but violated since its inception.

So I don’t buy the EMU is revenue constrained, not the US, claims, anymore. They are both politically constrained, and policy keeps changing.

Dear Panayotis

Exactly right.

best wishes

bill

BX12,

My argument is not to argue about the revenue constraint issue but only to point out that there is a reason for countries with less efficient production to issue their own currency while for those who are more efficient they have an advantage with a common currency because they can produce more!

Panayotis,

I’m not challenging the overall purpose of your argument, only questioning one of its premises. As I have said, I can’t help much with the main argument and only answered by way of a diversion.

Bx12,

When you are talking about bond yields, it’s not just the existing operational arrangements that count, but expectations of how things would play out in a crisis.

For example, a business may have a policy of spending less than 5% of its revenues on debt service. But that does not mean that when debt service costs reach 6%, the business defaults. When those costs reach 6%, the business makes an internal change, but does not default.

Creditors don’t care about the debtor’s internal policy, they care about the actual risk of default.

With the EMZ, the sovereign governments cannot count on the central bank to help them. The ECB may refuse. But United States bonds are “full faith and credit guaranty of the United States government“. Not “full faith and credit guaranty of the Treasury”. This is an important distinction. Arguing about the interdepartmental relations between the Fed and Treasury is relevant to the budgetary process, but it is not relevant to credit risk. Regardless of how independent you believe the Fed is from the Treasury, it is a branch of the United States Government, along with the Treasury. This means that U.S. Government can never be forced to default.

Greece or Ireland can elect to leave the EMZ, but that is also a default event, as the creditors were promised a payment in Euros. There is a non-zero risk that EZ governments may be unable to satisfy a debt obligation in euros. And given that risk, creditors are right to charge Greece a premium.

And Greece, instead of complaining about the yields, should change its operations so that it does not try to sell risky debt to the public. It should leave the Euro, force a restructuring/default, and issue its own currency.

Once the overdraft constraint is lifted, there is nothing operationally preventing payment on a bond or anything else.

But Congress can still choose not to pay; i.e. default.

bill: “”Of-course, they also could have simply stopped issuing debt altogether and gone on spending.”

bx12: “Of course, but has it ever happened in the US? ”

Lincoln financed the Civil War with Greenbacks.

And Tally Sticks were used in England for centuries, up until the early 19th century.

Yes, fewer imports, more exports, a more competitive economy, and higher levels of domestic output would clearly worsen their sovereign debt position. Look at how the bond markets are punishing the UK! A deficit of 11% of GDP and are forced to pay a usurious yield of 3.55% for 10 year debt, which is a negative real yield.

anon: \”The truth of course is that the US treasury is actually revenue constrained – due to the no overdraft rule.\”

Congress is not revenue constrained. It has the power of the purse, and the power to create money. The Fed is an agent of Congress, as is the Treasury. (OC, this does not mean that the Executive Branch is merely an agent of the Legislative, but Congress controls the creation of money.)

bx12 and anon,

this whole discussion about applicability of constraints seems really senseless and is a waste of time.

In a pure gold-standard and fixed exchange rate any government CAN spend more than its revenues. The fact of pure gold standard or fixed exchange rate does NOT change anything. Government CAN and it is full point here. Like everybody (you and me) can though we also have constraints. The problem here is not whether it can or can not but in the financial consequences of such decisions. And financial consequences are obviously different for an issuer of currency and for an user of currency. USA government is the issuer. And regardless of any operational, temporal, legal and any other constraint it will not face anfinancial constraint. Greece and any EMU nation is a user of currency and therefore operational, temporal, legal and any other constraints DO matter because they are imposed on Greece externally and are therefore binding in financial sense.

Dear Bill,

Regarding on the settled issue of the LT rates. As a point of clarification, I am sure you will agree that buying all offered LT bonds in the secondary market the CB will run into an inflation constraint as inflationary expectations and currency depreciation from the rising reserves will put pressure with increasing prices and inflationary premia on private debt transactions. At some point this inflation risk will constrain further purchases by the CB.

RSJ says: Tuesday, May 25, 2010 at 12:23 Bx12,

“When you are talking about bond yields, it’s not just the existing operational arrangements that count, but expectations of how things would play out in a crisis. ”

You’re not to find much opposition from me on self-evident truths such as the one above, but I think you’re extrapolating from them to the conclusion that “And Greece, instead of complaining about the yields… should leave the Euro, force a restructuring/default, and issue its own currency.”, without really taking up the arguments I put forth.

Min says: Tuesday, May 25, 2010 at 15:21 bill: “”Of-course, they also could have simply stopped issuing debt altogether and gone on spending.” bx12: “Of course, but has it ever happened in the US? ” Lincoln financed the Civil War with Greenbacks. And Tally Sticks were used in England for centuries, up until the early 19th century.

Thanks, so from that I know that at least in the case of a ruinous war, the US gov would stop issuing debt altogether.

So if a war, I mean a big one, erupted in the middle east, the EZ, would have no choice but surrender, because it is revenue constrained, although to the French, this is hardly a consideration : they would be more than happy to collaborate with the oppressor, and entertain them with their French cancan, gourmet food and all.

Sergei says: Tuesday, May 25, 2010 at 20:46 bx12 and anon,

“Greece and any EMU nation is a user of currency and therefore operational, temporal, legal and any other constraints DO matter because they are imposed on Greece externally and are therefore binding in financial sense.”

Thanks for giving us a mock fair hearing, while gently reminding us of the party line.

Here is some creative ideas how to solve the European crisis. 🙂

EU can help Greece by exiting the eurozone

“It turns out that the solution to Greece’s problems in particular and the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone in general is simple. European nations–especially Germany–must now pull together, show solidarity with Greece and act in unison: Member countries should do the sensible thing, and all exit the eurozone. This would have to be done simultaneously with a compulsory exchange of all bank deposits into local currency at the original euro conversion rate. After this one-off transaction at a fixed exchange rate, each currency would start to float.

This simple step would solve the European sovereign debt problem–and not only that of Greece–in one stroke: While all national debt would become external debt denominated in a foreign currency (the euro), this euro would be without the backing of any economy. It would collapse, reducing the local currency value of euro debt to virtually zero.

Effectively, the Year of Jubilee would be called: …“

The Central Bank sets rates by adjusting the base money supply. Money, as opposed to an interest-bearing security, is fully liquid, and this liquidity has value. If I have $300, I want it in cash. If I have $3000, that’s about the point where I consider putting some of it into a security to earn interest. If I have $30,000, I definitely want most of it to be earning interest. If rates go up, I’m willing to hold less cash in order to gain more income. This curve, desired liquidity vs. the available rate, is what allows the CB to set rates by changing the base money supply.

So in general, deficit spending is rate-neutral, because it creates its own demand for interest-bearing securities. If deficit spending creates a pile of dollars in the private sector, but aggregate liquidity preferences don’t change, then the holder of those dollars will want to exchange them for bonds. I suppose he could just sit on his pile of dollars, but if that’s more than his liquidity needs, it’s irrational to forego whatever income is available. Asset transactions within the private sector — one individual buying stocks or gold or Euros or whatever from another private individual — don’t matter, it just changes the identity of the individual who has a pile of dollars.

Traditionally the CB sets the short-term rate and lets markets figure out the yield curve relative to that. Longer-term rates then reflect expectations about future short-term rates and future inflation. Not everyone will hold the same expectations, the market price simply reflects the average at which the market clears. The CB could just as easily set the 10-year rate, and let the market figure out both shorter- and longer-term yields relative to that. Likewise, they could choose any single constraint — for example, controlling the weighted average of yields, using the amount of debt outstanding at each yield as the weights, sets the total “borrowing cost”, while still leaving the market free to determine the slope of the yield curve.

The question, though, is whether the CB can simultaneously set both short-term and long-term rates with a functional secondary market, whether they can do it but only by totally buying out the market for one or the other, or whether they can’t do it at all. I think that it can only set both rates if it chooses a relationship between the two that’s fairly close to their “natural” relationship, with the amount of “twist” that it’s capable of inducing being limited by the size/composition of it’s balance sheet assets relative to the market’s range of preferences at different durations. Suppose that with short-term rates fixed at 1% and longer rates floating, the market 10-year rate would be 4%. Further suppose that the CB wants to bring the 10-year rate up to 5% without changing the short-term rate. So it sells 10-years from it’s balance sheet and buys up 1-years. If the CB’s balance sheet is “deep” relative to private bondholders, this can work. Some fraction of those bondholders think that the appropriate rate for 10-years is between 4% and 5%, and they will be willing counterparties to this operation. If that fraction is small relative to the size of the CB’s balance sheet (the number of 10-years that they have available to sell), the operation will work. If most of the secondary market believes that that yield curve is too steep relative to the fundamentals, the CB won’t be able to supply all of the 10-years that market wants to buy at that rate.

So the CB is fairly limited in it’s ability to adjust the steepness of the yield curve, because their balance sheet is small relative to the total stock of debt outstanding. If the Treasury got involved, however, there should be no limits although markets at some durations might become very thin. Treasury can accomplish the above operation by reducing the amount of short-term debt that they rollover, instead increasing 10-year issuance. To do the opposite, they could buy back and retire 10-years early, funded by additional short-term issuance. If they try to bring down the 10-year rate, relative to short-term, to a level that the vast majority of the private sector believes is too low, they will have to rebuy almost all of the outstanding 10-years, and the market becomes thin, but in principle they can.

/L,

Richard Werner who originated the term “quantitative easing” wrote that article and said the policies that Japan implemented were the opposite of what he proposed. He said at the time it wouldn’t work and has been proven right. He is a critic of the euro from the start and the focus of monetary policy to control inflation. He is also in tune with what Bill and MMT write about the workings of the monetary system, and also proposes stopping the issuance of bonds. He teaches at the University of Southampton. He wrote the following two books on Japan that are relevant from a MMT perspective, and is a critic of Richard Koo. I’d say his book is more relevant than Richard Koo’s book on Japan because he understands the monetary system.

The New Paradigm in Macroeconomics: Solving the Riddle of Japanese Macroeconomic Performance and Princes of the Yen: Japan’s Central Bankers and the Transformation of the Economy (Paperback)

MMT claims to have uncovered the widely under-estimated power that a fiat currency system potentially and universally confers to a nation.

Most illustrating is Mosler’s Law : There is no financial crisis so deep that a sufficiently large increase in public spending cannot deal with it.

That universality and applicability is put into question by the view (Repeat after me : the US is not Greece) that the EZ is a bit of Frankestein, beyond redemption, as a monetary system.

The argument is made by purporting that Greece, for example, has lost its sovereignty and is the user of the currency, like a US state, which is functionally, not politically revenue constrained.

That is blatantly, technically not true : Anon ( I think ) and I recognize that government spending is a Euro issuing operation, which is not to say there aren’t complications, under a MU, which in turn is not to say they can’t be fixed, at least in theory.

While the EZ has institutional arrangements that constrain deficit spending, they have not been binding, empirically. The US congress is liable to a change of balance between the two main parties resulting in a drive to deficit reduction, as occurring in the UK at present. In either jurisdiction, under a fiat currency system, such constraints are self imposed.

Lastly, the ECB is by not fundamentally different from any CB and matches the BOJ and the Fed in terms of significance.

On a historical level, the untold underpinning of the rhetoric above is that Greece somehow erred, perhaps as a result of drinking Ouzo and taking too much sun at the same time, in getting into a situation it would not wholeheartedly have accepted, had it been sober. Hence the hangover, and the best way to get over it, is to backtrack.

The legal reality, is that they have transferred, not abandoned, some regalian prerogatives, in the best democratic tradition, and that the EZ is now the relevant entity.

Only far distant observers who never played soccer can reduce the EZ to a multinational that can spin off one of its entity to bring out the value of the latter.

This misses the historic significance. Today’s vagaries of the EZ must be weighed against the past 1000 years of rising and falling empires, wars, genocide etc., and the potential for the next 1000 years.

BFG says:

Wednesday, May 26, 2010 at 10:58

“He wrote the following two books on Japan that are relevant from a MMT perspective, and is a critic of Richard Koo. I’d say his book is more relevant than Richard Koo’s book on Japan because he understands the monetary system.

The New Paradigm in Macroeconomics: Solving the Riddle of Japanese Macroeconomic Performance and Princes of the Yen: Japan’s Central Bankers and the Transformation of the Economy (Paperback)”

Interesting.

I agree, Richard Koo believes in crowding out, for example, although he finds ways to downplay and hammer his call for deficit spending, which is probably more effective to convince the mainstream crowd.

From Werner. The cause of Japan’s recession and the lessons for the world:

“There are a # of policies the gov could have adopted itself such as ceasing issuance of gov bonds and instead funding public sector borrowing requirements through borrowing from the commercial banks. ”

“Or it could have issued gov paper money, which would have monetized fiscal spending without the burden of interest payments (as Kennedy did in 1963).”

Is he (Werner) showing an understanding of MMT here? I’m not sure I get the borrowing from cial banks part.

Lilnev,

I symphathize with your effort to analyse the debate about the LT structure. My suggestion to you is to realize the dynamics involved since the factors affecting LT rates are several with feedback effects and knowledge of control theory will show you the complexity of attempting to do so. As Bill, RSJ and I agreed, control can only come and be effective if the secondary market is internalized by the CB. This of course is not optimal because any attempt to do so will cause transaction costs and inflation risk from inflationary expectations as excessive reserves rise and currency depreciation occur that will defeat the CB policy interest target and bring the interbank rate to zero. Of course the CB can internalize all primary issues and this also has transaction costs. Thus if the state does not want public debt to be held by the private sector it should spend by crediting bank accouns or issue currency.