The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

German hypocrisy and lunacy

I haven’t much time to write a blog today (travel and other commitments). But I have been examining tax revenue data for the EU in the last day or so as part of another project and thought the following might be of interest. The analysis is still unfinished (by a long way). But to the news – I laughed when I read the story from Der Spiegel (March 12, 2012) – Germany Fails To Meet Its Own Austerity Goals – which listed Germany as a serial offender in the hypocrisy stakes. I also laughed when I read that the German Finance Minister, in between games of Sudoku, told a gathering in Berlin yesterday that (as reported in a Bloomberg video) “deficit spending is the wrong way to bolster economic growth” and that “People who believe you can generate growth without pursuing budget consolidation have “learned nothing from the experience of the crisis.” The combination of staggering hypocrisy and manifest arrogance (thinking that the world is so stupid that they actually believe austerity will deliver growth) seems to have reached new heights.

Der Spiegel reports that while EU nations:

… are expected to implement tough austerity measures amid the debt crisis … Germany isn’t setting a very good example.

Apparently, “Berlin failed to reach its own austerity goals in 2011. And despite pressuring its neighbors to save, Germany is behind this year too.”

We learn that while the Germans have been prosletysing about austerity throughout Europe and essentially pushing the damaging fiscal compact onto the region, they have failed to exercise the same degree of discipline over their own fiscal aggregates.

Der Spiegel reported that:

… the German government didn’t reach even half of its planned savings in the federal budget. Only 42 percent of the spending cuts …. [proposed] … were actually not implemented … only €4.7 billion ($6.16 billion) of the €11.2 billion in austerity measures stipulated by the savings package actually took shape in 2011.

That is clearly one of the reasons that the Germany economy has not tanked in the same way that the Greek economy has.

Appparently, while the German government has “planned €19.1 billion in savings” for this fiscal year, they have implemented “less than half” and so will miss that target too.

This hypocrisy is not new. Please read my blog – The hypocrisy of the Euro cabal is staggering – which documents how the Germans violated the SGP for several years from 2001 to 2005.

At that time, if they had have operated within the SGP rules (that is not maintained the level of fiscal stimulus they actually did) then their economy would have probably fallen into recession.

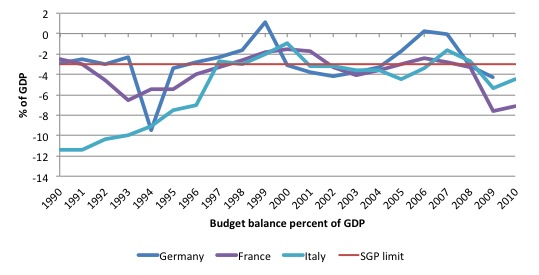

Consider the following two graphs taken from the detailed government expenditure and revenue data available from Eurostat. The first graph shows the annual evolution of the Budget Deficits (as per cent of GDP) for the “core” EMU nations (Germany, France, Italy) from 1990 into the convergence period leading to the creation of the common currency and to 2010.

The red line is the SGP upper limit deficits (3 per cent). Between 2001 and 2005, Germany violated the Treaty without penalty. France violated it between 2002 and 2004 and Italy between 2001 and 2006.

Why didn’t the Troika form then and along with all the rest of the mainstream commentators demand fiscal austerity for these nations. Why didn’t the EU pursue penalties under the Treaty (which the SGP is contained) against France and Germany?

The so-called corrective arm of the Stability and Growth Pact is called the excessive deficit procedure (EDP) which the EU’s ECFIN calls the “dissuasive arm”.

ECFIN write that:

The EDP is triggered by the deficit breaching the 3% of GDP threshold of the Treaty. If it is decided that the deficit is excessive in the meaning of the Treaty, the Council issues recommendations to the Member States concerned to correct the excessive deficit and gives a time frame for doing so. Non compliance with the recommendations triggers further steps in the procedures, including for euro area Member States the possibility of sanctions.

Fines of up to 0.5% of GDP are allowed for in the Treaty.

Germany was the nation that insisted on the inclusion of the SGP (and as I have noted previously wanted it to be called the “Stability Pact”). They were the first to trangress against it.

This ECB Occasional Paper (published September 2011) – The stability and growth pact crisis and reform says:

When it came to implementing the Stability and Growth Pact in a rigorous manner, the first test was failed. Faced with a need to fully apply the provisions of the corrective arm of the Pact in the autumn of 2003, France and Germany, among others, blocked its strict implementation by colluding in order to reject a Commission recommendation to move a step further in the direction of sanctions under the excessive deficit procedure.

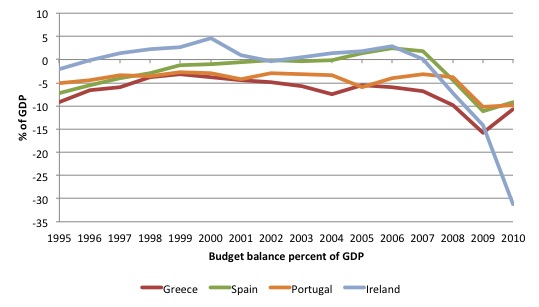

Now consider this graph which shows the budget history since joining the EMU of Greece, Spain, Ireland and Portugal. The intense cyclical deficits are clear in the recent years.

If you consider the two graphs together you would find that the only nations that actually ran surpluses in the common period were Ireland and Spain.

While Germany and France were “living it up” on budget deficits and then bullying the EU Council of Ministers to turn a blind eye to their (stupid) regulations, Ireland and Spain were acting like model EMU citizens.

This juxtaposition is not making a case for punitive action against Germany or France but is rather arguing that the rules are contrary to sound fiscal management and their presence (rather than enforcement) creates an environment – a pretext – for the bullies of Europe – the Troika – to impose whatever ideological slant they want on things.

And now, Der Spiegel reports that Germany is at it again. Laughable really.

And then there was the comment by the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble that:

People who believe you can generate growth without pursuing budget consolidation have “learned nothing from the experience of the crisis

Which has to rank among one of the quotes of this century really – for the sheer arrogance of it.

If you were to believe him then he must think exactly the opposite to what almost everyone else, other than the neo-liberal deficit terrorist zealots, have actually learned from the crisis. The countries that are going backwards are, largely, those who have engaged in Troika-style fiscal consolidation whereas those that are showing signs of life have not attempted to go down this path, although their senior politicians keep trying to steer their nations in that destructive direction (for example, Japan).

By definition, a nation cannot grow without spending. That is, the way we define economic growth. I know there are controversies about how we measure growth, especially in relation to broader concerns relating to environmental damage, non-paid household work predominantly performed by women, and other issues.

But within the national accounting framework, growth in spending equals GDP growth – in both real and nominal terms.

There are 3 broad sectors – the private domestic sector, the external sector, and the government sector. The. first two sectors sum of the non-government sector.

Spending has to come from these sectors. A recession is typically characterised by a reduction in the growth of private domestic spending (consumption and investment) which also impacts on the external sector balance because one nation’s imports are another’s exports. Import spending is a function of domestic income growth, which is driven by domestic expenditure.

This is typical behaviour has been very evident in the recent crisis, and the Eurozone hasn’t escaped the trend.

Fiscal consolidation, by definition, involves reductions in net public spending, which imposes fiscal drag on the economy. In certain circumstances, that is, when non-government spending growth is robust enough, this will not damage economic growth.

But it is clear, in the current climate, that non-government spending growth is not robust. In that situation, fiscal consolidation undermines growth.

The neo-liberal mantra of the 1990s that active fiscal intervention would damage economic growth because the private sector would react to the rising deficits by increasing their own saving (to fund expected future tax hikes), has been categorically shown to be false in the current crisis.

There is no empirical content in the German finance minister’s claim.

The evidence is clear – austerity is killing growth and private confidence is deteriorating not improving. Any claim that fiscal consolidation will promote growth and that a private recovery is imminent is just a statement of religious doctrine – there is no theory or evidence to support it.

There was an interesting Working Paper from the Bank of Spain (its central bank) early in 2011 – Endogenous fiscal consolidations – by bank researchers Pablo Hernández de Cos and Enrique Moral-Benito. I have referred to it before.

This paper sought to validate the claims that nations like Denmark had grown after a major fiscal contraction. It is not widely quoted by the journalists, presumably because it refutes the findings of the “darlings of austerity” (such as Alesina, A., and S. Ardagna (2010) “Large Changes in Fiscal Policy: Taxes versus Spending”, Tax Policy and the Economy, Editor: R. Brown, vol. 24. NBER. and Giavazzi, F., and M. Pagano (1990) “Can Severe Fiscal Contractions Be Expansionary? Tales of Two Small European Countries”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual, pp.95-122, MIT Press., etc).

But it is a thorough piece of research with very foreboding conclusions.

Essentially the research is motivated by the claims made by economists (and policy makers) that “fiscal consolidation episodes could be expansionary for an economy” which challenge “the broadly accepted Keynesian notion concerning the existence of a positive fiscal policy multiplier”.

They explicitly say that the empirical studies which are used to justify austerity:

… are based on empirical analyses in which they first identify periods of drastic and sizeable budget cuts within a panel of OECD countries, and then perform a descriptive analysis of the sample characteristics of macroeconomic aggregates, mainly GDP, before, during, and after the year in which the consolidation episode took place. The main conclusion from this literature is that fiscal adjustments are often followed by an improved growth performance, which is interpreted as evidence of non-Keynesian effects during fiscal consolidation episodes.

The important point to note is that a “positive correlation between fiscal consolidation episodes and GDP growth does not necessarily mean that fiscal consolidations generate economic growth”.

The authors argue that the extant literature claiming fiscal austerity drives growth makes a major error – it “assumes that the consolidation episode is exogenous to GDP” which ignores the causality issue.

They say that it is also possible that the “positive correlation between fiscal adjustments and economic growth may be the result of a positive effect from GDP growth to fiscal consolidation instead of the other way around ….

Their contribution is to conduct the investigation between fiscal consolidation and economic growth within a framework that a allows for the fiscal response to be endogenous – that is, reactive to the state of economic activity.

What do they conclude? Their main conclusion:

… is that endogeneity biases are chiefly responsible for the non-Keynesian results previously found in the literature; hence, fiscal adjustments are found to have a negative effect on GDP growth.

That is, the studies that provide justification for imposing fiscal austerity in the belief that it will generate economic growth are fatally flawed because their research design assumes causality is only one way.

Overall, the paper concludes that once you control for “endogeneity biases”:

… fiscal adjustments are found to have a negative effect on GDP growth.

These results are being borne out every day all around the world. The US is growing and unemployment is falling because their failing polity cannot get their austerity act into gear as yet. The economy is still enjoying the fiscal stimulus (although it was never large enough).

Many economies in Europe are declining fast and unemployment is rising because they have imposed fiscal austerity on vulnerable economies. Spending creates income. Cutting spending destroys income. Private confidence is not engendered by cutting public spending – exactly the opposite.

There is a time when fiscal consolidation occurs without damaging growth. It is when growth becomes robust enough to turn the automatic stabilisers around – so that they start to boost tax revenue and reduce welfare spending.

The reason the “slippage” is occurring in the EMU is because the automatic stabilisers are undermining the discretionary cuts in net spending being imposed by the Troika. But that is no surprise. It is exactly what we would expect. By imposing pro-cyclical discretionary cuts, the governments are ensuring the counter-cyclical automatic stabilisers will kick in hard.

Tax revenue falls, welfare spending rises (if it hasn’t been hacked) and budget deficits rise – slippage.

Exactly the opposite happens when discretionary net spending is increased – the counter-cyclical discretionary net spending stimulates growth which turns the automatic stabilisers around.

The Bank of Spain research paper finds exactly that. Again – no surprise. The German ideologues provide no credible evidence. Just mantra.

In this context, I have been examining trends in tax data in the EU. I will provide a more comprehensive report in due course but the following may be of interest.

This Eurostat site – Tax revenue statistics is very helpful if you wish to learn about how Eurostat deals with tax revenue data.

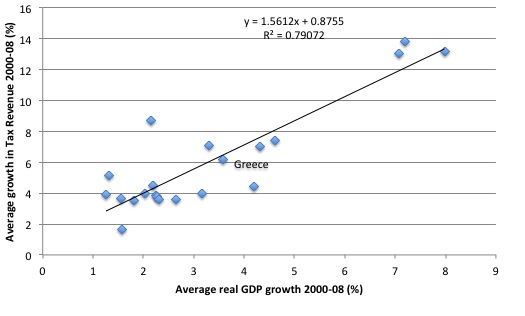

The first graph shows the relationship between average real GDP growth between 2000 and 2008 (horizontal axis) and the average growth in tax revenue over the same period (vertical axis). The black line is a simple linear regression (equation statistics noted) and there is clearly a positive relationship over this period, which is consistent with both intuition and credible economic theory.

Stronger real GDP growth is typically associated with stronger employment growth and stronger tax revenue growth from both wage and salary earners and the corporate sector.

There is nothing exceptional about Greece – it experienced mid-range real GDP growth and mid-range growth in tax revenue over that period. The Baltic nations are out to the right of the graph.

If I was to model this relationship more rigorously, I would find a very strong positive, statistically-significant relationship consistent with the information in the graph.

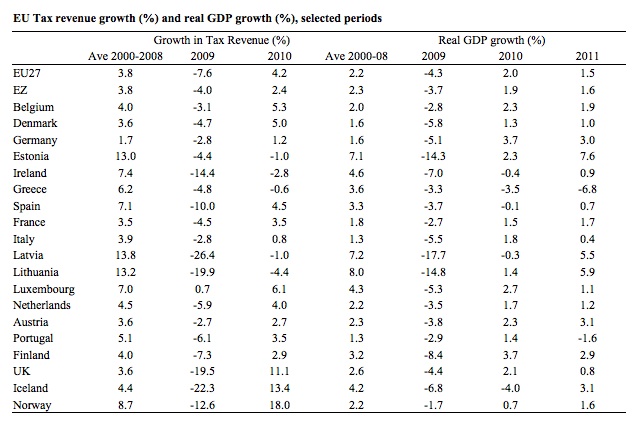

The next graph plots the same relationship for 2009 (blue diamonds) and 2010 (red squares). The Baltic states are once again the extreme observations for 2009 only this time at the opposite end of the growth continuum.

It is interesting, that for 2009 the relationship remains positive but has weakened. I haven’t done any serious econometric analysis of this data, but I’m sure that tests for asymmetries in the time series would find that to be so.

If you consult the accompanying table (see below), you will see that Greece is still unexceptionable – in the sense, but the decline in its tax revenue was consistent with the decline in real GDP.

However what is interesting, and unexplained at this stage, is what happens to the relationship in 2010. Greece is now the outlier and the relationship appears to switched to being negative – that is, rising growth is associated with declining growth in tax revenue. I’m investigating this in more detail and will report back when I understand it better.

2010 was the year that fiscal austerity was broadly imposed on the Eurozone nations. However some of the other nations did not follow suit. I suspect that divergence in policy stances may be at the bottom of this story.

This table provides the underlying data for the previous 2 graphs.

In a later blog, I will show the extent to which the lost tax revenue impacted on the budget outcomes for various EU nations. Preliminary analysis shows that the cyclical decline of tax revenue impacted to the order of several percentage points on the budget bottom-line for several EU nations.

What the data shows is that the so-called automatic stabilisers drove the budget outcomes in many EMU nations beyond the SGP threshold. So without the government making any discretionary changes in its spending and tax policies in response to the collapse in aggregate demand, the fiscal rules would have been violated in many cases.

The fact that a cyclical swing can produce such an outcome raises questions about the validity of the fiscal rules.

The German-inspired fiscal compact, which the EU nations are now signing up for will be even worse. The dynamic they impose upon the region is one of entrenched stagnation.

Conclusion

I have run out of time today. I was also going to comment on last Thursday’s ECB Press Conference (March 8, 2012) as well because the new ECB boss really outlined his conceptualisation of fiscal austerity. There is no doubt that they consider “union” to be more important than prosperity. I will come back to that another day.

The Press Conference also demonstrated categorically that the ECB is not an independent, impartial player in the EMU. Mr Draghi was lecturing member states about their fiscal policy settings. But then the German government were pressuring the ECB to stop its provision of liquidity to the banks.

In the article – Germany Turns Up Pressure on ECB – (March 10, 2012), an ally of Dr Merkel said:

I hope that the ECB acknowledges its limits and quickly rakes in the money

Which limits are they exactly?

The general point is that with political leaders that Europe is burdened with the outlook is very gloomy.

That is enough for today!

No, they haven’t. The authoritative source for government spending is the 2011 Budget Report of the Finance Ministry (short variant), and the maximum allowed debt growth as part of the long-term constitutional debt brake policy was undoubtedly achieved, which means that Germany fullfiled its own plans to the letter – in fact the net debt was clearly far lower than agreed, 17.7 billion Euros instead of the 48.8 billion Euro as it was originally planned for 2011 when the budget was adopted.

What Der Spiegel is reporting is that various planned spending cuts were not implemented to the full extent, which is due to the fact that real economic growth in 2011 was significantly above predictions, as have been the tax revenues and employment numbers, which in turn means that the spending cuts were not needed in order to achieve the austerity goals that Germany agreed to. I fail to see what’s “embarassing” about not cutting spending when you don’t need to. If Greece would have the same economic growth, revenue increase, unemployment numbers and a budget deficit of 1% in 2011, I don’t think anybody would be up their asses about cutting spending.

We will see if Germany’s budget will remain under control for 2012 – the economic perspectives are certainly not as good as they were for 2011, but so far I fail to see a reason for it to not achieve the budget deficit and debt reduction goals it has set itself, even when not cutting spending by as much as planned. It is of course still far too early to say for sure, and a lot will depend on the economic context within and without the EU, and of course especially if there are any increased demands on additional funds and guarantees for the various help packages.

But there is a clear pressure for higher wages from various public and private branches, there will be a slight increase in pension benefits in 2012 to align themselves with the increases in wages that took place in 2011 and there is even a possibility for slight tax cuts in the health benefits area (due to the massive increase in reserve funds that took place in 2011), so there is reason to expect a continuation of the trend for stronger internal consumer spending in 2012.

Well said indeed!

Andrei,

“I fail to see what’s “embarassing” about not cutting spending when you don’t need to.”

The point Bill seems to be making is that the causality was in the other direction. That is precisely because Germany did not make its cuts target that the debt goal was achieved in spades.

I fail to see how a government can make plans to reduce spending and yet within a year successfully anticipate they don’t have to reduce spending by so much, and then change course, governments don’t do that.

Clearly the causality must have been in the other direction, in that they were simply unable or unwilling to make some of the cuts, and so met their debt target.

Kind Regards

I am not sure how that would function – the spending cuts proposed were relatively modest (about 11 billion Euro) and out of the planned cuts, more than 40% were anyway realized. Also, the unimplemented parts of the cuts were in areas which really don’t necessarily make that much of a direct difference in the development of the economy (cuts were proposed largely in administrative costs, some specific social security spending and in costs for the interest rates), certainly not short term (i.e. within a few months).

But the difference in sheer economic growth, the corresponding increases in tax revenues on the one side and the reduced spending on unemployment benefits on the other side, was on the order of tens of billions of euros, which no matter what kind of multiplicator effects you want to consider could hardly have been directly caused by a 4 billion lack of decrease in government spending.

Also, Bill’s claim Germany wasn’t fulfilling its own austerity goals – and my point was that Germany most certainly does (so far, at least), just not quite as planned back in 2010. In fact, it managed to be ahead of some parts of those plans: for instance, Germany actually had two more years (till 2013) at its disposal to reduce its deficit below 3%, as mandated by the procedure initiated by the EU in winter 2009 against Germany as a result of its budget deficits in the first year of the financial crisis, yet it achieved this goal already in 2011.

Sure they do – growth predictions are made when the budget is initially conceived (in this case, autumn 2010), and they are continually compared with the actual development of the real economy in the budget period (in this case January to December 2011). GDP growth numbers are available on a monthly and quarterly basis, and reports about actual government spending are possible on even a shorter timeframe. Realized tax revenues for previous years are reported in the early spring timeframe, and they influence the current budget predictions as well, and so do the official statistics about employment and unemployment .

If there would be no uncertaintity and flexibility in government spending and revenue, then there would be no difference between planning and reality. But if you look at the link I gave above, all the table data includes numbers on the planned budget numbers (the so-called “Soll-2011” column for those who don’t speak German) and the realized ones (“Januar bis Dezember 2011” column). Some numbers match almost perfectly, others don’t – as with any real-world economy, what the government plans and what they actually can and will do as the budget period unfolds are two different things.

Fair enough Andrei, and I am probably misunderstanding Bill’s point too.

It seems strange to me that a parliament can vote for a budget which may or may not be implemented fully. That is certainly not how it happens in the UK. Unless their are specific measures in the budget for a change of course mid-way through the year.

A further point is that much of Germany’s fortunes are in the hands of international demand for its products and services. This might be much harder to predict if austerity and government debt problems in the rest of the Eurozone triggers a global slow down in demand for Germany’s tradeables. Even with no “contagion” to the rest of the world I wonder if a slow-down within Europe generally will affect Germany’s exports. Perhaps you would know more about this.

I don’t know, maybe Bill can comment when he has the chance on what exactly he was trying to say, but given the rethoric he employed (“hypocrisy and lunacy”), I am pretty sure that he was trying to claim that Germany is failing to implement its own austerity policy, which I contend is clearly not the case.

As for the budget question, I am not familiar with the workings in the UK, but surely there is a mechanism to do revisions to the budget, as need be, even within the budget period? I can’t imagine that there is no flexibility or mechanisms to reallocate resources in the face of diverging developments on the markets, compared to the base predictions of the initial budget plan. Of course, the amount of changes can’t be immense, but there are various methods through which the german government can change implementation details or postpone certain measures.

I don’t think anybody would disagree with this, certainly not the german government – that’s why its predictions for GDP growth in 2012 are far more restrained, exactly because of these factors. The 2012 budget was planned with that in mind, and generally assumes a significantly cooled down export sector, especially in the first half of the year, compensated to a certain extent by a moderate rising in internal consumer spending and by constant unemployment/employment numbers.

But as with any estimates, they can prove wrong, so there is no guarantee that the budget deficits will remain so low and/or that all the austerity measures will be implemented as planned – longer term it is clear that the 2010 austerity plan which addressed the mid-term 2011-2014 period will not function as originally intended, because several components like for instance the financial transaction tax or the nuclear fuel tax will either not be implemented at all, or will be delayed (thanks to EU-wide disagreements in the case of the transaction tax) or will not achieve the hoped for amounts (due to the difficulties presented by the change in long term nuclear power policy as a result of Fukushima, in the case of the nuclear fuel tax).

@CharlesJ

“I wonder if a slow-down within Europe generally will affect Germany’s exports.”

2/3 of German trade is conducted inside the union (which is also the case for EU trade in general).

So i believe you can figure out the answer now.

Andrei,

I would say that Bill’s point is that the rest of Europe and the Eurozone countries with high deficits do not need to implement austerity either (given the capacity of the ECB), as the pursuit of balanced budgets is lunacy, unless of course it happens to be consistent with full employment for a particular country.

Yes, that much is clear, I know what Bill’s general point always is. I was reffering however to his specific point on Germany’s “hypocrisy and lunacy” about its fiscal austerity in this blog post.

@CharlesJ

What is lunacy is the very flawed design of the currency itself.Its the design that creates the need of balanced government budgets.The governments are practically turned into households or businesses that do need to keep their finances in balance.Since they are revenue contrained (which wasnt the case back when they could issue their own currency) they are forced to cut deficits and even achive surpluses (at least primary).Ofcourse this creates the problem of economic depession since a government surplus equals to private sector deficit.Sure someone can argue that if the economy has a current account surplus ,then a government surplus is possible without hurting the private sector but by definition we cant all be net exporters thus we cant all have current account surpluses.

Hi Bill,

I have four really basic questions regarding MMT. Any response would be much appreciated:

1. Do you think that MMT might be compatible with small government and low taxes, or is it inherently biased towards big government and high taxes? (I’m assuming that MMT would always involve some form of the JG if it were to be fully implemented).

2. Does MMT require a degree of nationalisation (i.e. of banks/ corporations) and strict regulation, or is it compatible with no nationalisation and a more hands-off approach to regulation?

3. Would you say that MMT economists have different political and ideological positions, or are you all more or less the same?

4. Do the main MMT economists have different understandings of what MMT is or of how it could be implemented?

Thanks,

Phil.

Crossover,

Yes I believe you are right on both points.

Andrei

What about Bill’s other point. That Germany violated the SGP limits between 2001 and 2005? Surely an element of hypocrisy here?

Also, that Schauble said: “People who believe you can generate growth without pursuing budget consolidation have “learned nothing from the experience of the crisis”. Lunacy? Certainly can be argued.

You address one point but ignore two others that support his use of those words. That seems rather selective and undermines your argument.

@PH Warren Mosler seems to believe in small government – Read ‘7 Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy’ and makes the point that MMT can embrace both small and big government.

“I haven’t much time to write a blog today…”

Yes, only 4 diagrams, 1 table and 2897 words. Pathetic…

PH asks the questions quoted herebelow.

.

“Do you think that MMT might be compatible with small government and low taxes, or is it inherently biased towards big government and high taxes? (I’m assuming that MMT would always involve some form of the JG if it were to be fully implemented).”

The notion of a Job Guarantee is not part of the MMT analysis. Bill Mitchell advocates JG on the basis of MMT insights. Modern Monetary Theory remains a descriptive, rather than prescriptive, approach. Policy makers, in formulating policy, ignore MMT insights (or even go against them) at their peril.

More precisely, other people’s peril.

.

“Does MMT require a degree of nationalisation (i.e. of banks/ corporations) and strict regulation, or is it compatible with no nationalisation and a more hands-off approach to regulation?”

Again, MMT does not “require” anything more than understanding what’s actually happening in the real world of modern-state finances, national economics and bank operations. MMT shows what is more likely to happen when an action is taken. But the choice of action (e.g. bank nationalisation; less regulation) remains tied to what one desires as an outcome.

.

“Would you say that MMT economists have different political and ideological positions, or are [they] all more or less the same?”

From their writings, it can be clearly seen that the gamut of ideologies (aka prescriptive theories) varies from capitalism to social-democracy.

.

“Do the main MMT economists have different understandings of what MMT is or of how it could be implemented?”

There are differences, e.g. Circuitism.

Dear Andrei,

The hypocrisy lies with the fact that Germany has been for years promoting and still promotes austerity around the Eurozone, without taking into account much. Have you seen any representative of the German goverment advising fiscal expansion anywhere or congratulating countries for such a policy, even in countries with a positive external balance?

If Germany was practicing what it preaches, it would have followed through with the promised spending cuts. But, lest we forget, Germany was, along with France, the first violators of the Maastricht Treaty limits on deficit and debt ratios. The adjective “hypocrites” is not to be contested. The German government has earned it !

As to the lunacy, it lies with the fact that, if fiscal relaxation should be “allowed” for Germany (despite its rhetoric and its own commitments), it should positively be encouraged, nay mandated for countries like Greece. The policy forced on Greece, instead, is a pro-cyclical policy, one which amplifies the dire situation of the economy. Hence, the (most aprpopriate) term for the loonie tunes directives emanating from Schäuble & co.

.

By the way, note that in real-life loonie tunes, no one truly dies. Elmer Fudd comes back in the next episode, alive and well, to fight evil (and Bugs Bunny) another day. That’s not the case however in modern-day Greece. The austerity is killing people, beyond the millions it throws into abject misery. So, Mitchell is actually being kind to the Germans. If this were premeditated, they cannot invoke insanity. These are crimes against humanity.

@ Vassilis / PH

I believe Vassilis is not correct above to regard the Job Guarantee (JG) as some optional feature in MMT. As far as I am aware the credited co-founders, first users with clear rights to use of the expression ‘MMT’, Randall Wray, Bill Mitchell, Warren Mosler, Scott Fullweiler, all regard the Job Guarantee as an essential feature & part of necessary ‘functional finance’ for both price stability & an employment (aggregate demand) ‘floor’.

Those who disagreed with this position split off to form something they call ‘MMR’, principally Cullen Roche & a few others. Randall Wray at New Economics Perspectives has written some superb blogs on this issue imo.

In my own modest scribbling in support of MMT, I often make the point that the Job Guarantee (imo) should not be considered as an aspect of the government/public sector, but separate.

The JG jobs are intended to be a flexible & fluctuating in quantity buffer stock &, importantly, not crowd out or compete with either private or ‘normal’ public sector employment. The most important element is the ‘automatic stabiliser’ function of JG wages in maintaining aggregate demand/spending in the downward part of the business cycle. But nor is it to waste idle labour resources. There are endless numbers of social & environmental NGOs & charities that can never afford sufficient labour to achieve their goals. There are real & valuable community benefits to be gained when such labour resources can be made available. And benefits to JG participants themselves in remaining active in employment. Elements of skill enhancement & training can easily be integrated too.

It should be obvious that the choice of relative size of public/private sector may be decided separately by the political/democratic structures pertaining. Only when these two sectors combined fail to produce sufficient jobs does the JG come into play.

Here in Ireland, we had something similar in a CE or Community Enterprise scheme, sadly now almost completely run down or defunct in many areas. The CE jobs were part time, locally based & paid a useful supplement above normal unemployment benefits. Our local town’s (voluntary sector) Environmental Group were major participants developing public spaces & enhancing the town’s tourist presentation in projects that simply could not have been afforded otherwise. A number of long term unemployed that I know personally went on to gain employment & self employment in such things as building, landscape gardening & horticulture.

Unfortunately, Ireland is using a foreign currency (Euro) and has chosen to aquiesce to all the ruinous demands of the Euro banksters & their crony politicians in a debilitating program of growth killing austerity & has no fiscal space to resurrect such programs. (The Environment Group still exist but are entirely voluntary now.)

My own suggestion is that the currency issuing authority (a re-mandated ECB) should finance a JG program in every Euro country to restore growth & prosperity quickly. Giving time to address the fundamental flaws of the EMU & implement the remaining required elements of MMT & functional finance in due course.

I see absolutely no reason why this cannot be done, and especially galling that the ECB can create €1 trillion in the last 3mths, to give to banks, but nothing whatever is being done for the unemployed or to promote growth. Sure, the money is nominally 3 year loans, but I have no doubt whatever that such ‘loans’ will simply be rolled over indefinitely, as desired.

Dear Mike Hall,

I will readily concede that “the credited co-founders, first users with clear rights to use of the expression ‘MMT’, Randall Wray, Bill Mitchell, Warren Mosler, Scott Fullweiler, all regard the Job Guarantee as an essential feature & part of necessary ‘functional finance’ for both price stability & an employment (aggregate demand) ‘floor’.”

That is indeed the historical record.

However, MMT represents a scientific endeavor and not some art project. The “founders” can define the nomenclature and impose demarcations as they see fit – but that would be, precisely, a case of subjective demarcation. MMT analysis of macro-economy, banking operations and national finances is not incomplete without the notion of a JG. For many people, such as the “founders”, it may seem like MMT analysis, once accepted, “cries out” for a JG scheme.

But this does not make MMT any more prescriptive than Anatomy is in the medical science.

Cheers.

Dear Mike Hall,

I forgot to mention that, as it happens, I support JG !

🙂

Cheers.

Mike, good to see you contributing here. You’re an oasis of sense in the comments section on the Irish Times website (union-bashing, demonising of the unemployed, resentment of public sector employees, conspiracy theories, it’s all there). I agree with you completely on the old CE Scheme in Ireland – if anything, it should have been expanded, but now, when it’s needed most, it’s been all but junked. Now all there is is the detestable ‘JobBridge’, an ‘intern’ scheme whereby private enterprise gets free labour from overqualified people on the dole (plus fifty euros), with the likelihood of such people being re-consigned to the dole upon expiry of their Government-funded period of ‘internship’.

Great post, by the way, Bill. I think the message that the Germans were early (and long-term) transgressors of the so-called ‘Growth and Stability Pact’ is one that should be repeated loudly and often. But it should also be emphasised that they were correct to do so. They may have to do so again once their main export market can’t buy any of their wares anymore.

@Ciaran Ofcourse they were correct to do so due to the simple fact that the Maastricht Criteria is pure bullsh!t.There is no explanation for example,why the maximum allowed deficit is 3%?Why couldnt it be 2% or 5% ?Or why maximum allowed debt is 60% ?Seriously if the maximum allowed deficit was 5% nobody would have ever spoke of a target of 3% of gdp.That was just a limit that was decided upon no logical grounds.

But unlike other things there is no fallacy of composition here…if Germany was correct to exceed the limit,everybody else exceeding it is equally correct.And lets not forget that the German government didnt have to “overspend” in the middle of a global crisis…budget deficits are more important now than back then.

Crossover – agreed. My point exactly. ‘Peripheral’ nations in the eurozone are being prevented from making an equally correct decision by a supine and incompetent political class, backed up by an over-powerful ECB.

Vassilis Serafimakis : The notion of a Job Guarantee is not part of the MMT analysis. Don’t think this is exactly the right way to put things. Job Guarantees can be understood as objects & consequences of MMT analyses.

For many people, such as the “founders”, it may seem like MMT analysis, once accepted, “cries out” for a JG scheme. But this does not make MMT any more prescriptive than Anatomy is in the medical science.

True, but a bit more tiresome & trivial precision is helpful. It is possible to talk about policies, “ideologies”, reasoning correctly, “descriptively”, replicably about them, without being ideological or non-descriptive in any interesting way. Everyone, not just the founders, can see the logic behind the “crying out”. The “crying out” reasoning is part of MMT.

Knowledge of anatomy shows that decapitation will kill you, while cutting off your pinkie toe is a topic for a Seinfeld episode. (And might sometimes be necessary.)

Most people say: Killing is bad, and usually not funny. So + Anatomy => Don’t decapitate people.

Serial Killers say: Killing is good. So + Anatomy => Let’s chop off heads, not toes!

MMTers reason: Unemployment & price instability is bad + MMT nominal insights => Job Guarantee.

Vampire squids reason: “Unemployment is good, to keep the rabble in line” + MMT => Governments should unemploy as many lesser people as possible, so they die, and us vampire squids can take their stuff.

Nothing wrong or inconsistent about anybody’s analysis. MMTers, Serial Killers or Vampire Squids. And it’s reasonable to call all of them Anatomy (or Medical Science) or “MMT”. It is quite possible to reason correctly, scientifically in a uniform way with logic anyone trained can follow, reason “descriptively” about prescriptions. Indeed, one hopes one’s doctor does. (Keynes would say dentist 🙂 )

Dear Some Guy,

Thanks for the response.

I do not disagree with your thinking. However, note that not every economist agrees that decapitation is bad, as such! As you are no doubt aware, the notion of the free economy’s “destructive creativity” promises new (and better) heads growing after we decapitate – or something similar. Only, of course, stated in far friendlier terms. Which is exactly the issue.

And which is why my aim is to get as many people as possible to understand and agree on MMT’s insights as descriptive, i.e. ideologically neutral. If people undestand that promising X while undertaking policy Y is impossible, and that, instead, X’ will be the likely result then people might realize that X’ is contray to their interests – i.e. as bad as a decapitation.

The doctor might promise that “after the pain” the patient will get better, but if the patient sees, through purely anatomical knowledge, what’s truly in stock for him, he will hopefully change doctors.

Regards,

Vassilis Serafimakis

I do not disagree with your thinking.Didn’t think you would. And which is why my aim is to get as many people as possible to understand and agree on MMT’s insights as descriptive, i.e. ideologically neutral. Yes, that is why I responded. I agree wholeheartedly with you on this. E.g. the term “developers” leans toward this view we both oppose, with the comparison to developers of software, who have much more artistic license than scholars/scientists. It’s not necessary for anyone to share a particular notion of public purpose to understand sound MMT arguments. What is necessary is understanding “public purpose” or “society” as a concept, which everyone does, even if they pretend they don’t, even Maggie Thatcher a few decades ago.

MMT is a big step on the road to economics as a form of dentistry. There isn’t any particularly ideological about MMT. There’s a little bit of ideology in dentistry too – my old dentist liked to inveigh against the modern “destroy the tooth to save the tooth” ideology. But basically dentists & patients agree that tooth decay is bad. Problem is that in economics we have a powerful oral bacteria & candy lobby with opposed purposes, who want toothaches & creative tooth destruction, even though they know most people don’t. They therefore deceive people to think candy is good for teeth & toothbrushes, flossing & mouthwash are evil unnatural govern-oral intervention, which will destroy your teeth “in the long run”, while laissez-les-bacteria-faire is the best policy.

Speaking of Elmer Fudd, I’ve found he is very useful in explaining and understanding economics. Was explaining some neoclassical/mainstream hallucinations to my wife the other day. She didn’t understand until I said it in an Elmer Fudd voice, when she cracked up & got it right away. Now I always feel I understand a mainstream idea better if I imagine Elmer explaining it to me. This is another forgotten insight of Keynes, as when he spoke of “the sort of thing which no man could believe who had not had his head Fudded by nonsense for years & years.” 🙂

Regards,

Some Guy