I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

Look after the unemployment, and the budget will look after itself

There was a Wall Street Journal article (March 5, 2012) – The High Cost of the Fed’s Cheap Money – which is full of statements like “could eventually lead to an economic calamity” etc. The WSJ article basically rehearses a confused form the old supply-side tradition of the pre-Great Depression era where the claim was that “supply creates its own demand” (so-called Say’s Law) which was shorthand for the proposition that flexible prices and interest rates would ensure that whatever was supplied would be purchased. The same sort of arguments were used in a recent lecture to Harvard EC10 students by the Director of the US Congressional Budget Office. It is extraordinary that these myths, which were part of the body of economic theory that led the world into the current crisis, still have currency. They should start by understanding what Keynes meant when he said “Look after the unemployment, and the budget will look after itself”.

Please read my blog – The old line back to free market ideology still intact – for more discussion on this point.

The article ticks all the neo-liberal boxes:

… quantitative easing (QE) and the zero interest rate (ZIRP) … increase the risk of future inflation, obscure the true cost of the unsustainable fiscal policy the federal government is running, and transfer wealth from savers to debtors … [and] … reduce long-term economic growth by punishing savers, reducing saving and investment over the long run. They encourage the misallocation of resources that at a minimum is preventing the natural rebalancing of our economy and could sow the seeds of another painful boom-bust.

Focusing on the claims about saving, the view expressed is based on the defunct Loanable Funds Doctrine, which was the dominant theory of interest rate determination prior to the Great Depression.

As I have noted previously, there are two broad assertions that come from this doctrine. First, government spending drives up interest rates and crowds out private spending, which is asserted to be more productive. Second, lower interest rates will reduce saving and squeeze available investment funds, which stifles growth.

The only problem is that the theory is not an accurate depiction of the way the economy and individual behaviour within it works.

The theory of loanable funds is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

The story went like this. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

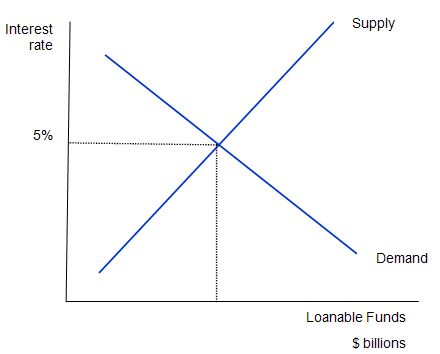

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds. The current real interest rate that balances supply (saving) and demand (investment) is 5 per cent (the equilibrium rate). The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc). The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

Note that the entire analysis is in real terms with the real interest rate equal to the nominal rate minus the inflation rate. This is because inflation “erodes the value of money” which has different consequences for savers and investors.

Modern macroeconomics textbooks perpetuate the idea of a loanable funds market. In Greg Mankiw’s Principles, which is representative, we are taken back in time, to the theories that were prevalent before being destroyed by the intellectual advances provided in Keynes’ General Theory.

Mankiw assumes that it is reasonable to represent the financial system as the “market for loanable funds” where “all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.”

He claims that this “market works much like other markets in the economy” and thus argues that (p. 551):

The adjustment of the interest rate to the equilibrium occurs for the usual reasons. If the interest rate were lower than the equilibrium level, the quantity of loanable funds supplied would be less than the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The resulting shortage … would encourage lenders to raise the interest rate they charge.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

Mankiw also says that the “supply of loanable funds comes from national saving including both private saving and public saving.” Think about that for a moment. Clearly private saving is stockpiled in financial assets somewhere in the system – maybe it remains in bank deposits maybe not. But it can be drawn down at some future point for consumption purposes.

Mainstream economists think that budget surpluses represent national saving in the same way. However, once we understand what a budget surplus is we quickly understand that they are not even remotely like private saving.

Budget surpluses actually destroy liquidity in the non-government sector (by destroying net financial assets held by that sector). They squeeze the capacity of the non-government sector to spend and save. If there are no other behavioural changes in the economy to accompany the pursuit of budget surpluses, then as we will explain soon, income adjustments (as aggregate demand falls) wipe out non-government saving.

I will return to what drives savings at the macroeconomic level later.

The other point to reflect on is the way the banking system operates. Please read Money multiplier and other myths if you are unsure. The idea that banks sit there waiting for savers and then once they have their savings as deposits they then lend to investors is also alien to the way the banking system works.

The loanable funds doctrine thus suggests that budget deficits “crowd out” private spending. For example, Mankiw alleges:

Mankiw says:

One of the most pressing policy issues … has been the government budget deficit … In recent years, the U.S. federal government has run large budget deficits, resulting in a rapidly growing government debt. As a result, much public debate has centred on the effect of these deficits both on the allocation of the economy’s scarce resources and on long-term economic growth.

So what would happen if there is a budget deficit. Mankiw asks: “which curve shifts when the budget deficit rises?”

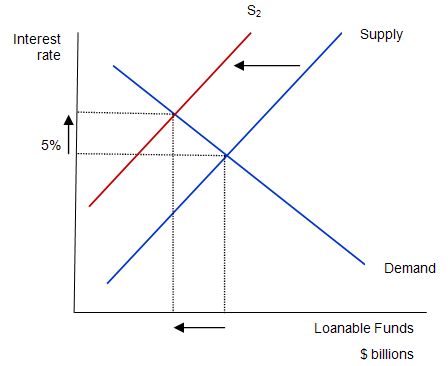

Consider the next diagram, which is used to answer this question. The mainstream paradigm argue that the supply curve shifts to S2.

Why does that happen? Their logic is as follows: national saving is the source of loanable funds and is composed (allegedly) of the sum of private and public saving. A rising budget deficit reduces public saving and available national saving. The budget deficit doesn’t influence the demand for funds (allegedly) so that line remains unchanged.

The claimed impacts are: (a) “A budget deficit decreases the supply of loanable funds”; (b) “… which raises the interest rate”; (c) “… and reduces the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds”.

Mankiw says that:

The fall in investment because of the government borrowing is called crowding out …That is, when the government borrows to finance its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. Thus, the most basic lesson about budget deficits … When the government reduces national saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. Because investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

But of-course, the WSJ article is arguing exactly the opposite and has one foot in the loanable funds doctrine and another foot somewhere else. The somewhere else foot is recognising that the interest rate is not determined in a real market (mediating the flows of saving and investment) as is the conception held out by the loanable funds doctrine.

The WSJ article clearly recognises that the central bank can control both short-term and longer-term investment rates should they desire to do so.

But the “loanable funds doctrine foot” thinks that by controlling these rates private saving is underminined which, in turn, according to this logic, causes a shortage of investment funds.

It is a very confused analytical framework. Here is what is wrong with it.

First, sovereign governments engage in irrational behaviour by issuing debt at all. Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

The decision to borrow is largely based on erroneous logic (whereby it is claimed that debt-issuance reduces the inflation risk of government spending). That logic is clearly wrong. The inflation risk is inherent in any spending (private or public) and intensifies as the economy reaches full capacity. Government spending adds to bank reserves after all the transactions have played out and borrowing just drains those reserves. But that is the topic of another blog.

Given governments borrow, doesn’t this increase the claim on saving and reduce the “loanable funds” available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates? Doesn’t low interest rates discourage saving and reduce the funds available for investment?

The answer to all questions is no! Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) recognises that central banks may hike interest rate hikes if they form the view that inflation is likely to rise. There is also the possibility that the rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

MMT proposes that the demand impact of interest rate rises are unclear and may not even be negative depending on rather complex distributional factors.

Remember that rising interest rates represent both a cost and a benefit depending on which side of the equation you are on. Interest rate changes also influence aggregate demand – if at all – in an indirect fashion whereas government spending injects spending immediately into the economy.

But having said that, the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on these mechanisms. In fact, they assume that savings are finite (and determined in the loanable funds market by the prevailing interest rate). They also assume that government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans.

The result competition for the “finite” saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

The loanable funds doctrine presumes that there is some finite quantity of saving that is available for loans and the demand for loans is then rationed by the interest rate. So investment was limited by available saving.

But in the economy we live in, investment is not limited in this way. Banks create loans which fund investment. In turn, the rise in aggregate demand increases income which then is consumed or saved by households in desired proportions.

Spending brings forth its own saving is a fundamental principle of modern monetary theory derived from its traditions in functional finance. Keynesians also understand this.

Keynes said in his Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, Volume XXIX, pages 80-81 that:

For the proposition that supply creates its own demand, I shall substitute the proposition that expenditure creates its own income.

If firms are optimistic then they will formulate investment plans and build capital and productive capacity reflecting their long-term expectations of a return. This is what Keynes called “animal spirits”.

They will seek loans from the bank system (among other sources) to facilitate these investment plans. There are a sequence of monetary adjustments that then accompany the creation of the deposit after the loan is agreed. At some point, once the deposit is drawn on, the bank would have to ensure there were sufficient reserves to facilitate clearing in the payments system (so cheques didn’t bounce).

In some cases, no reserve adds would be required. For example, if the cheque drawn on the bank was deposited into the same bank by a third-party.

Once the investment flows occur, the production process generates a volume of output which as Keynes noted increases income.

Saving rises because households rarely spend all they earn (in aggregate).

At some future point, if saving is higher than the entrepreneurs expected (that is, consumption spending is lower) then unsold inventory manifests at the end of the cycle. Firms react by cutting back production and income falls. The falling income causes saving to fall and the process stops until the inventory cycle is finished and firms are selling the proportions of consumption and investment goods they desire.

Of-course, the state of rest that is achieved may result in very high unemployment and is thus undesirable. This is what the unfettered market forces would generate in the absence of governments using their fiscal capacity to fill the spending gap left by the saving desires.

But the point is that aggregate saving reacts to income changes not interest rate adjustments.

Even within the logic of the WSJ article, if the low interest rates were killing the incentive to save, then there should be a massive excess demand for funds at the low interest rates (demand for funds for investment greater than the supply of funds from saving).

The WSJ article doesn’t really consider that point, only to say that:

The Fed is hoping the lack of return in certificates of deposit and bonds (or more accurately, negative returns, adjusted for inflation) will prompt investors to take on more risk by investing in stocks, high-yield corporate bonds and other investments. This is pushing people who have a low risk tolerance to take on more risk than may be advisable.

So private investors are apparently not rational and are pushed into options they do not like by the price system.

Either way, there is not a dramatic growth in private investment in the US. Further, if there was then the yields on government bonds would start rising as investors diversified into more risky assets and saving would rise.

All of which isn’t occurring which gives you another reality check that this type of framework is unhelpful in thinking about what is going on.

The reality is that investment is largely driven by expectation of future returns (revenue flows at the existing cost of capital). Higher interest rates will tend to render the marginal project unprofitable but in a buoyant economy higher cost of capital can be easily offset by higher expectations of revenue.

In the “supply-side” tradition, the WSJ article also claims that:

Prosperity does not come from spending; it comes from work, saving and investment.

In other words, a denial that an economy could enter a crisis due to falling aggregate demand.

Famous English economist Alfred Marshall said that you had to understand the movement of both blades of the scissors when cutting paper. He was referring to demand and supply.

It should be readily apparent that firms have cut back their real production during the crisis because spending has been insufficient. Further, in doing so, they have curtailed investment plans because they realise they can meet the current demand with the existing productive capacity.

If there was more spending, then firms would start investing more (accessing funds via the credit system) and households could maintain a stronger growth in consumption spending and increase absolute saving (and maintain a desired ratio).

In early February 2012, I considered the the latest Budget and Economic Outlook from the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) – which many commentators have interpreted as representing a dire future for America.

In this blog – Monetary movements in the US – and the deficit – I outlined an argument, based on MMT logic, that suggested the forecasts only augured well for the US.

This UK Guardian article (March 4, 2012) – Unemployment matters more than GDP or inflation – agrees with that assessment. In relation to Europe and the UK the writer says that:

The austerity gamble hasn’t paid off. Fiscal consolidation has failed to spur growth or boost employment.

Fiscal stimulus, on the other hand, works. The US has had 23 consecutive months of private-sector job growth, with 3.7m new jobs created over the past two years thanks to Barack Obama’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. US unemployment benefit claims are now at a four-year low.

Which is why John Maynard Keynes said in a Radio Interview in 1933 (Reference: Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, Volume XXI, page 150) that:

Look after the unemployment, and the budget will look after itself.

This observation, is of-course, linked to the earlier discussion.

Economic growth starts with spending growth. Firms will not invest unless they can sell. So capital spending (investment) might spur growth but only if there is an expectation of consumption growth (whether public or private). Firms are largely indifferent to who purchases the output they produce.

I have never heard of a private company who turned back a government order on the basis that such spending was “inflationary”, “unproductive”, “undermining freedom” etc.

Spending patterns and the public-private composition will vary according to the state of industrialisation (early stages more capital formation relative to consumption) and demography (older societies probably require proportionately more public spending).

But it is spending that drives growth and reduces unemployment.

Which brings me to a recent presentation – Choices for Federal Spending and Taxes that the CBO Director Douglas Elmendorf gave to young (impressionable) economics students at Harvard University. You can download a PDF version HERE.

Simon Johnson called this lecture “an emotional plea for the return of political sanity. You should share it with your children” ((Source).

I call it a neo-liberal beat-up of monstrous proportions, which draws on many of the myths analysed earlier.

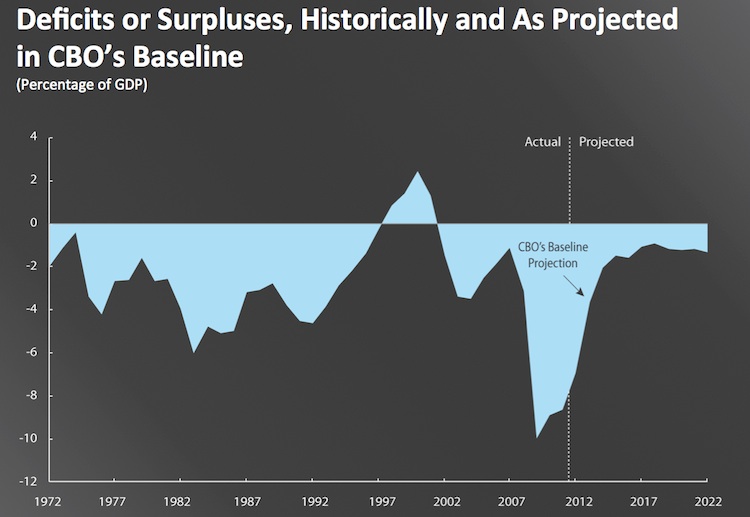

This graphic was the first in the slides presented by the CBO boss. Note the term in the heading – “Historically”. I guess none of the students in Mankiw’s first-year economics class at Harvard (where the CBO boss’s lecture was given) were alive before 1990. So for them a graph going back to 1972 might appear rather “historical”.

And it has the effect of displaying the current deficit as being “historically” large. But it is all relative and reliable budget data for the US goes back to at least 1930.

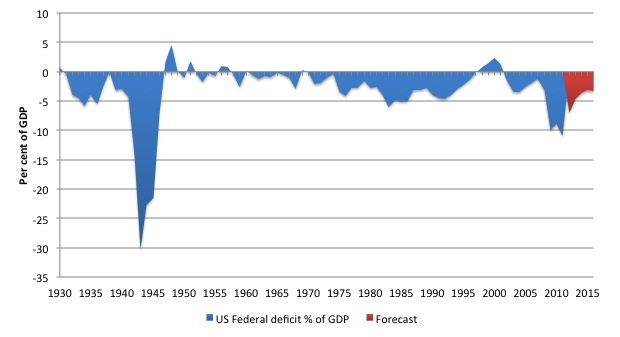

Here is the US federal budget deficit from 1930 to 2011. The data comes from the US Office of Management and Budget. As I have indicated in the past this truly historical graph tells us that: (a) the US has had much larger deficits (as a percent of GDP) in the past; and, most importantly, that (b) deficits at the federal level are the norm and surpluses are the exception.

The other point to note is that every time the US has run federal surpluses a recession has followed soon after.

I wonder if quizzed the EC10 class at Harvard about the history of federal deficits, their relationship to growth and saving etc how many would give an accurate historical rendition. My guess is very few would pass the test. And then we could ask them to explain Japan over the last 20 years.

But the “historical” CBO slide was a precursor to Slide 5 which was entitled Harms of High Federal Debt and contained the following dot points:

• Reduces the amount of saving devoted to productive capital and thus results in lower incomes than would otherwise occur.

• Leads to high interest payments, meaning that additional tax increases or spending cuts are needed to make fiscal policy sustainable.

• Makes it harder for policymakers to respond to unexpected problems, such as financial crises, recessions, and wars.

• Increases the likelihood of a fiscal crisis.

All statements are false and so we can conclude the EC10 students at Harvard are being indoctrinated rather than educated.

The first point about saving has been dealt with in the earlier discussion. The private demand for public bonds does not diminish the capacity of firms to access loans to build productive capacity. It is a lie to say otherwise.

Further, inasmuch as the ridiculous institutional arrangements that governments hang onto (as artifacts of the gold standard) whereby they unnecessarily issue debt $-for-$ to match deficit spending, the federal debt mirrors the accumulated deficits.

Those deficits allow aggregate demand to grow and “finance” the non-government desire to save. Sometimes (as now), the deficits might be too low relative to the private output gap. But always they promote growth.

Further, the federal debt is private wealth and the interest payments are private incomes.

Second, there is no evidence that tax rate increases or pubic spending cuts mirror the public debt ratio in any way at all. A sovereign government does not face a financial trade-off between interest payments and other net expenditure (which includes tax increases).

It does face such a real trade-off when the economy was at full capacity – that is, it cannot push more real output from the system and has to reduce its own spending or that of the non-government sector (via tax increases). But that is a different story to the one being made here by the CBO boss.

A sovereign government can always afford to purchase whatever is for sale in its own currency.

Third, a sovereign government can always respond to crises, unexpected problems etc. The previous graph should demonstrate the capacity of the government to increase its deficit to meet the challenges of depression and, then, war. It is an absolute lie to claim that a government deficit today reduces the capacity of the government to run a larger deficit tomorrow.

Finally, for a sovereign government which can control interest rates and issues its own currency there is no “likelihood of a fiscal crisis”. The only crises that we should be concerned about in terms of macroeconomics relate to unemployment and lost income opportunities (assuming environmental sustainability is not being violated etc).

Remember Keynes “Look after the unemployment, and the budget will look after itself”.

The CBO Director might reply that there were not “structural” deficit problems in Keynes’ day. This is a line that was curiously taken by Keynes’ biographer Lord Skidelsky in 1996.

He may be arguing unambiguously at present for fiscal stimulus using this same statement by Keynes (see – Cable’s attempt to claim Keynes is well argued – but unconvincing (January 27, 2012)) but in 1996 he appeared to be expressing a more neo-liberal view.

In this article (January 1, 1996) – Essay: Welfare without the state – he said:

The champions of the welfare state have a seductive alternative strategy. If European governments were to pursue expansionary monetary policies, unemployment would come down, growth would be faster, and budget deficits would dissolve in higher revenues and lower spending. ‘Look after unemployment,’Keynes once wrote, ‘and the budget will look after itself.’ This would be fine if budget deficits were purely cyclical, as they were in Keynes’ day. But they are now structural products of steady upward pressure on spending, combined with tax resistance. The welfare state is the primary cause of both, and thus contributes directly to the high interest rates which keep growth low and unemployment high. Moreover, it weakens the supply side of the economy by giving people less incentive to work and save. At its extreme, it produces social pathologies summed up in the notion of the ‘underclass’.

I doubt that he wants to be reminded of that 1996 claim.

My reply (which I will amplify in a future blog) to both the CBO director and Skidelsky circa 1996 is that the deficits in the US and elsewhere in the post-World War 2 period were definitely structural in origin (with cyclical fluctuations) and were the result of discretionary choices by governments to ensure their economies remained at full employment.

If there is more need (demand) for public spending to maintain services and income support for an ageing population then the resolution to that need will be political in nature. The government will always be able to accommodate that demand should the electorate desire it to. That desire will be expressed via the electoral mandate.

The other consideration is that while the government will always be able to meet the need financially, there is no guarantee that real standards of living can be met. But that is not a question of government solvency.

Conclusion

I have run out of time.

Maybe Greg Mankiw will invite an MMT economist to attend his EC10 class to present a rejoinder to the CBO lecturer. The students might actually learn something about the world they live in if he did.

That is enough for today!

The students at Harvard are paying for this stuff. Given the protests that occurred a few months ago about his course what are Mankiw’s views on consumer sovereignty?

Related to this “lost income opportunities (assuming environmental sustainability is not being violated etc)”, what would happen if the expansionary monetary policies are not backed-up with real resources (energy, water, metales, etc…)?

More generally, is MMT theory compatible with a world of finite resources? How does the MMT accommodate to that view?

AFAIK, MMT tries to generate growth through gov spending, but, what would happen if this spending cannot be achieved due to a lack of material resources?

Mankiw’s course, at about $5,000 per student (before they buy his book), can certainly afford to pay for outside experts to come in. Even from Australia.

“deficits in the US …. were the result of discretionary choices by governments to ensure their economies remained at full employment.”

I was wondering about this. If the “structural” budget balance is anything like the “full employment” budget balance, then cutting these deficits would simply ensure that the government cannot reach full employment – so why cut structural deficits unless it is the governments intention to avoid full employment. Such an intention would therefore be discressionary.

Here’s the worst part: these Harvard students might one day occupy the positions currently held by Gregory Mankiw and Douglas Elmendorf.

Hi Billy,

Doesn’t the rising stock market of the past two years tend to confirm that the QE’s have “pushed people(?)— to take more risk …….”?

Bill,

When will your textbook be released?

Cheers!

Hi Bill,

This may not be an appropriate place to ask this, but, considering MMT logic, I was wondering why governments impose large amounts of debt upon both undergraduate and postgraduate students? Obviously, there is zero connection between paying for tertiary education (academics, admins, *cough* pretentious Pro Vice-Chancellors etc.) and the need to impose said “cost” on students.

Is there any possibility that you could give your thoughts on this?

Cheers

Related to this “lost income opportunities (assuming environmental sustainability is not being violated etc)”, what would happen if the expansionary monetary policies are not backed-up with real resources (energy, water, metales, etc…)?

…

AFAIK, MMT tries to generate growth through gov spending, but, what would happen if this spending cannot be achieved due to a lack of material resources?

Inflation.

MMT doesn’t tell you can spend all you want the most stupid way one can think of and it will come out fine. No, it says you are not limited by nominal resources. How does MMT relate with a world of limited resources? Simple, it says you don’t have to undermine policies that bring about a better use of resources (investment in renewable energies, conservation efforts, recycling, education, etc.) because you don’t have the money.

Unemployment? Pah, what’s that?

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-O1sRJii9J0s/T1ZPsZE4FPI/AAAAAAAAAEA/qguB67Fenyc/s320/papademos_nairu.png