Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

Japan – where will the productivity growth come from? – Part 4

A few weeks ago I wrote this blog post – Japan – the challenges facing the new LDP leader – Part 2 (October 9, 2025) – documenting the viability of a fiscal expansion in Japan given the availability of idle labour resources, which are in short supply. I noted that the recent estimates from the Bank of Japan of the Labour Input gap were +0.47 per cent, which means the available labour force is working over their trend potential, and raise the question: How can output growth be possible with the labour capacity already well above potential? Which is what today’s discussion is about.

I note the regular comment that follows any discussion I provide about economic growth that I must be mad given that the world is operating at 1.7 times the regenerative capacity of the biosphere.

I know that and I have made the point often.

So you don’t have to keep making it as I am oblivious to the issue.

But with population growth, it is difficult to see economic growth as measured by GDP becoming zero.

Degrowth is not about zero economic growth.

It is about reducing the energy content of that growth and bringing our resource use back into the range of regenerative capacity.

The question posed in the introduction bears somewhat on the issue of productivity growth – that is, growth in output per unit of input.

If labour resources are scarce then to squeeze more output from the available labour requires either they work longer and/or they work smarter.

Hours worked

There is a perception that Japanese workers work long hours and so trying to get more out of the existing workforce by extending working hours would not be possible.

There are some misconceptions here.

First, historically, Japanese workers did work long hours.

In 1980, for example, the average annual hours worked per employed worker was 2,121 hours (around 42 hours per week).

The OECD average in 1980 was 1,919 hours.

Other countries: Australia 1,818; US 1,859; Germany 1,746; and the UK 1,619.

But that has changed significantly in the face of changing social norms and government policies encouraging lower legal hours of work.

So in 2024, the numbers were: OECD average 1,740; Japan 1,611; Australia 1,645; US 1,811 (2023 data); Germany 1,342 (2021 data); and the UK 1,496.

Second, Article 32 of the Japanese – Labor Standards Act 1947 (last revised 2018) – is clear:

(1)An employer must not have workers work more than 40 hours per week, excluding break periods.

(2)An employer must not have workers work more than 8 hours per day for each day of the week, excluding break periods.

But the damage is done via Article 36 (Off-Hours Work and Work on Days Off), which covers overtime.

Essentially, if the unions and the employer agree then it is open sesame.

Worse, is if the employee agrees (under pressure of course) to what is known as the ‘fixed overtime system’ – みなし残業 (Minashi Zangyo) or 固定残業 (Zangyo) then they can be required to work a set number of hours overtime without pay.

Third, the official data is a little misleading because it measures the ‘formal’ working arrangements rather than what actually happens.

In some sectors, there is informal pressure to work unpaid overtime hours as part of the loyalty to the company.

Further, there are social conventions that make it hard to get out of the ‘after work’ drinks, which can continue late in the night.

However, that informal practice is declining somewhat as the younger workers adopt different attitudes to the workplace than their parents.

There is also an increasing number (and proportion) of 派遣社員 (dispatch workers) and 契約社員 (contract workers) in Japan which blurs the picture – given those who are working full-time are in decline.

As social attitudes change and more women enter the labour force, they swell into these more casual positions.

My conclusion: there is probably scope to increase hours of work but it would likely be at the expense of the casualised workers who are already underpaid and insecure, which would further reduce the quality of work.

Not to be recommended.

The Productivity issue

I often think back to the work of – W. Arthur Lewis – who was a West Indian economic development theorist, who published a seminal book on the topic in 1955 (The Theory of Economic Growth).

That was a standard text when I did development studies in the late 1970s at the University of Melbourne.

It came after a famous journal article – Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour (published 1954) – which unveiled his dual-sector model of development.

Accordingly, a nation grows by expanding the ‘capitalist’ sector using labour resources in the ‘subsistence’ sector, the latter which he considered to be ‘backward’.

The subsistence sector has high rates of slack – more workers working than strictly necessary to do the work, which means the productivity in that sector measured by conventional standards is very low.

Thus, national productivity increases overall as labour is attracted to the growing, more capital-intensive sector.

The seemingly ‘unlimited labour supply’ available in the subsistence sector allows the higher productivity sector to grow without placing upward pressure on wages.

Profits are thus high and rates of reinvestment in productive capital are high, which spawns increased employment opportunities to allow the migration from the subsistence to the high productivity sector to continue.

Eventually, as the subsistence sector is reduced to its bare bones, wage pressures enter the picture – but by then the economy has traversed from undeveloped to developed.

W. Arthur Lewis was an optimist and didn’t consider the first world capitalists would take their profits and not reinvest back in the prosperity of the nation.

History tells us otherwise.

The point of the reference though is that to some extent Japan is a dual economy – at least that is what many economists think.

I see much more nuance but the mainstream see a high-tech, high productivity goods producing sector dominated by manufacturing and a low-productivity service sector where there are many workers on payrolls who do very little productive work.

If that encapsulation was accurate then Japan could tap into the labour resources in the service sector who allegedly are underworked and encourage their shift into the high productivity sector.

Remember that overlaying all this is a rather rapidly increasing dependency ratio – which means that there are few Japanese workers actually producing goods and services relative to those who are using them (the aged) and that problem is getting worse as the years pass.

So to maintain material living standards, the next generation of workers will have to produce more per head than their predecessors.

That is the challenge of increasing dependency ratios despite the mainstream economists telling us that the problem is that governments will run out of money paying for the pensions and health care.

The conventional narrative is that 70 per cent of workers in Japan are employed in the Service sector yet its productivity is very low.

The popular claim is that you enter a shop and get besieged by one worker after another who says hello, goodbye or nice day or some other thing but who seemingly does nothing much.

Visitors often scoff at the men with little wands that stand outside shopping centre car parks or public buildings directing traffic.

At Kyoto University there are stacks of these ‘traffic men’.

Visitors claim they do nothing very useful at all and just look important in their military (police) style uniforms waving their wands.

Surely they could do more productive work elsewhere is the question?

Things are not always what they seem to be especially when cultural blinkers are in place.

These men interact with the public and convey a great sense of community.

They go home after work each day to take care of their families and have pride in what they do.

One of these workers always smiles when he sees me arrive on my bike and waves me through with a welcome and じゃね (ja ne) which is an informal way to say “see ya later mate”, and indicates he knows me by now.

I smile, he smiles and we are both happier for the experience.

So on what universe are they doing ‘nothing’?

But the mainstream contention is that Japan could solve some of its labour shortages by redistributing its labour resources from the service sector where they are allegedly underemployed and retraining them to work in the goods-producing sectors.

Productivity would rise and there would thus be more room for real wages growth, which has been largely absent over the last 20 or so years.

There is truth in the contention but it does ignore the cultural aspects I referred to above.

It is true that the service sector has productivity levels (and growth) well below the manufacturing sector, but that finding is not unique to Japan.

Manufacturing productivity is considered high although growth in recent years has been low.

When we think of opportunities for productivity growth we can see two avenues:

1. Within-firm – improve practices within a given workplace – higher skills, improved equipment, etc.

2. Reallocation – reducing low-productivity firms/sectors and promoting high-productivity firms/sectors.

One has to be careful what one wishes for though.

As an example that I came across last year in Kyoto is the tatami mat industry.

Many local areas have little factories like this photo depicts (I took it just around the corner from where I live).

Small-scale manufacturing operations are scattered through residential areas in Kyoto.

This particular shop makes traditional tatami mats and serves a relatively small area.

They are intricately made and last a long time and maintain the craft through generations.

However, there is a major shift to large-scale manufacturing, particularly made in China mats.

The modern tatami mats are now substituting rice straw as the filling with polystyrene.

And the imported mass-produced Chinese mats are inferior to the mats produced in these small-scale plants in Kyoto – they are not as durable and quickly break up.

So while the ‘productivity’ of tatami mat manufacturing is rising as the local little operations disappear, the quality falls and all the related human experience and satisfaction are lost.

There are also dramatic variations in productivity growth within sub-divisions of the service sector.

The following graph shows two sections of the Retail Sector – general merchandise which has more than doubled its productivity since January 2000 (up to December 2024) and the dry goods and clothing (department stores etc) which has gone from 100 to 35.3 index points over the same period.

The dark lines are 13-month moving averages on monthly data (Source) to smooth out the monthly fluctuations which are shown as well.

Retail trade (Food and Beverages) since January 2010 have gone from 100 to 102.8 points – that is, static.

In the Wholesale trade area there are dramatic differences.

For example since January 2000 (index = 100), Wholesale trade (food & beverages) has gone to 212.7 points, Wholesale trade (Textile and apparel) 100 to 35.5 points; and Wholesale trade (machinery & equipment) 100 to 80.2 points.

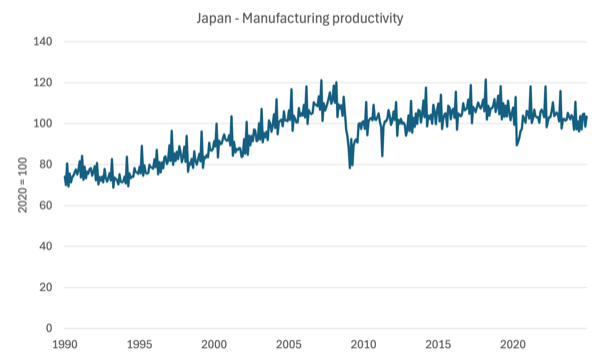

For Manufacturing, since 1990, productivity has grown by 39 per cent.

But since 2010, it has grown by just 2.2 per cent, a massive slowdown.

I will write more about this in further blog posts.

Conclusion

The conclusion from today is that there is probably scope for government to encourage capital investment in the goods-producing sector which has hit a flat spot in terms of productivity growth.

However, it is also facing labour shortages.

How much scope there is for reallocation from the service sector to the goods producing sector, without damaging what is nice about the place is questionable and I am investigating it further.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Going forward, the goal should be to release more workers from goods manufacturing, as robots do more of the work, just as workers were released from agriculture by mechanization.

Then we can consign the “productivity” narrative (‘output per worker’) to the dust-bin of history.

(Japan Times): ‘Factories in China installed nearly 300,000 new robots last year (2024), more than the rest of the world combined, the report found”.

China could already be subsidizing quality consumption for its poor (rather than chasing rich Western markets), given its vast manufacturing capacity (called “over-production” by paranoid Western manufacturers who can’t compete); but instead China is facing high unemployment and a housing crisis, because subsidization of (quality) consumption by debt-free treasury-issued money is illegal.

You request exemption from the laws of physics?

Continuous economic growth is not physically possible.

We run out of materials or we overheat the planet, even at 100% efficiency. It doesn’t matter how much productivity growth is achieved. You run out of basic materials or you overheat.

That’s the point of Dr. Murphy’s paper. In the limit, you can make the physical resource portion of the economy arbitrarily small, just enough to sustain life. (At a 2.3% growth rate, you hit hard limits in 200 years, give or take.)

At that point, economic growth must cease because the non-physical resource portion of the economy cannot grow once the physical portion is at the minimum necessary to sustain life.

I’d grant an exemption from the laws of physics for you, were one available.

“Limits to economic growth,” Murphy, T.W., Nature-Physics, July, 2022.