These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Japan challenges – is there really a labour shortage? – Part 6

This blog post continues my exploration of the available productive resources in Japan which would allow a nominal fiscal expansion to be accommodated without adding to the inflationary pressures. People consistently point to the low official unemployment rate as a proxy for a shortage of labour in Japan. It is good that the official unemployment is consistently low and that is a good thing. But the official rate might not be a very good indicator of the degree of labour market slack, especially as Japan has endured many years of low economic growth and falling real wages. A focus on underemployment probably provides a better guide to the availability of idle labour resources. That is what I consider in today’s instalment.

Remember that underemployment is defined in two ways:

1. Time-based: this occurs because a proportion of those employed desire to work longer hours at the same wage structure but cannot find the extra work (because total spending is insufficient to generate a higher labour demand).

2. Skills-based: this occurs when people are employed in jobs that are below the level in skill requirements that would be indicated by their level of education, training, and experience.

I spoke to a person yesterday in Kyoto, for example, who had a university education in industrial design theory and practice, but who was unable to find work in that field, and instead, was a shop assistant at a clothing shop.

That sort of mismatch represents skills-based underemployment.

He also wanted longer hours of work, which would represent time-based underemployment.

While the long period of stagnant growth would normally impact on the official unemployment rate, the attachment to long-term employment practices and a traditional disdain for sacking workers had meant that the slack has had to manifest differently – and in this case, it has revealed itself in two major ways:

1. Rising underemployment – rising part-time and non-regular employment.

2. Declining working hours.

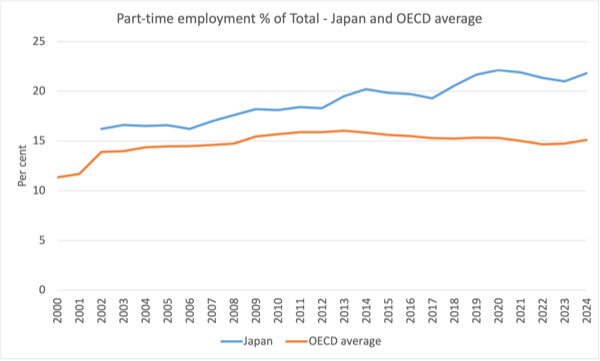

The first graph shows the evolution of part-time employment as a proportion of total employment from 2000 to 2024 for Japan and the OECD average.

In the 1980s (not shown), the proportion was always less than 12 per cent.

In 2002, 16.2 per cent of total employment in Japan was classified as part-time.

By 2024, this ratio had risen to 21.8 per cent, which means that around 2,064,160 workers who have shifted into working part-time relative to 2002.

In Japan, a person is classified as being employed if they worked for pay or profit for at least one hour during the reference week.

So the difference between unemployment and employment is just one hour of work.

That, by the way, is a common demarcation and reflects the ILO standard.

The main reason for this rise in part-time work as a per cent of total employment is the lack of employment opportunities.

Since 2013, the proportion of workers working less than 34 hours compared to total hours worked has risen from 30.7 per cent to 33.4 per cent in the June-quarter 2025.

This suggests that underemployment is increasing.

Of those part-time workers (who work less than 35 hours), 10.8 per cent of them want to work more hours.

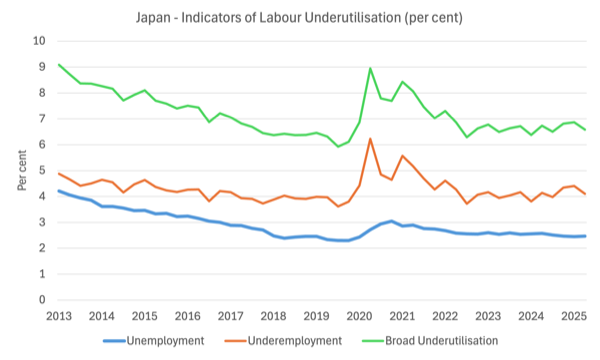

The data supplied by the Japanese National Statistical agency (e.Stat) is only consistent from March 2013 to the June-quarter 2025.

I was able to put the time series together to get something that was meaningful and the following graph shows the results.

In the March-quarter 2013, the unemployment rate was 4.2 per cent, and the underemployment rate was 4.9 per cent, which gives a Broad Labour Underutilisation indicator (the sum of the two) of 9.1 per cent.

By the June-quarter 2025, official unemployment had dropped to 2.5 per cent and underemployment was 4.1 per cent, which gives a Broad Labour Underutilisation indicator of 6.6 per cent.

In other words, 6.6 per cent of the available workforce want to work more hours, the unemployed are working zero hours and the underemployed less than they desire.

The available data (without putting in a special request) doesn’t allow me to compute the extra hours that those who desire them actually would like.

So I cannot at this stage (for the blog post) compute an hours-based underutilisation indicator.

But even with these calculations, it is hard to conclude that there is no idle labour.

One of the reasons for the rise in part-time employment relates to the way the demand-side of the labour market has responded to changes in external conditions – trade competition, etc.

The cultural expectation of life-time employment is still in place but under threat.

Rather than become stuck with a permanent worker which must be provided with secure work until they reach retirement age, corporations are increasingly reducing the offers of regular, permanent employment and replacing the positions with what are referred to as non-regular jobs.

These jobs are mostly part-time and carry no promise of certainty of permanency.

The employer can then meet the vicissitudes of the economic cycle by hiring and laying off these non-regular workers to suit the flux of their sales.

One way to detect that trend is to consider the – Employment Referrals for General Workers – data provided by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan.

It allows us to compute the job openings-to-applicants ratio, which gives us an idea of how strong the demand-side of the labour market is relative to the supply-side for non-regular and regular workers in Japan.

The ratio is consistently higher for part-time workers relative to the regular workers, which indicates that firms are more willing to higher the former group and offer non-regular working arrangements rather than tie themselves up with regular workers who must be kept on in most situations.

There is also strong evidence that mobility between the increasing non-regular cohort and the regular workers is very limited, harking to the classic dual labour market structure where the desirable conditions available to primary labour market workers are made possible because the flux of the cycle is borne by the secondary workers who face insecure employment and low wages.

The problem with this state is that it provides a massive disincentive for employers to invest in new capital which would deliver productivity bonuses and provide the scope for higher real wages to be paid.

We can’t talk about this ….

The aspect of the Japanese labour market that is not often spoken about in polite company is the implicit discrimination against foreign workers in Japan.

Article 14 of the – Japanese Constitution – makes it clear that officially there is no discrimination allowed:

All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin.

Further, Article 3 of the – Labor Standards Act – notes that:

An employer must not use a worker’s nationality, creed, or social status as a basis for differential treatment with respect to wages, working hours, or other working conditions.

There are also other laws in place to render discrimination by nationality illegal.

But tell that to the employers.

There is a plethora of research that demonstrates that the unemployment rates of foreign workers in Japan are significantly higher (particularly for those who come from other Asian countries) than it is for Japanese nationals.

Further, access to permanent employment as opposed to casual work is very difficult for foreign workers.

Conclusion

I am trying to work out how I can calibrate the labour surplus in terms of hours of work and to reconcile the skills issue.

The analysis so far though tells me that while the Japanese population is ageing and shrinking, which leads to the claims that there is a major labour shortage, the reality is different.

There is a significant labour pool that can be offered more hours of work and retraining to ensure their skills match the needs of the new jobs.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Sounds like the reasons for Japan’s labour skills demand-supply mismatch are little different to other wealthy nations. At least Japan doesn’t seem to be using its high wage rates as a means of enticing skilled migrants from low-wage countries, thus robbing some of the least productive countries of their most productive people – an annoying feature about Australia while 1.5 million Australians wanting paid work are left underutilised or not utilised at all.

Don’t mainstream economists tell us that when you offer a price that is below what is required to entice a prospective seller to sell something, market forces compel you to offer a higher price? And pigs might fly? Just another reason why real wages are stagnant and most productivity gains go to capital not labour.