I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

Societies that exclude their youth will rue the day

The British Office of National Statistics released a new report yesterday (February 29, 2012) – Young people in work – 2012 – which provides a scary view of how austerity is impacting on the future British adults. It shows that the employment rates of 16-24 year olds in Britain have fallen dramatically in the least several years and that they are bearing the brunt of the recession. The evidence once again highlights the nonsense of imposing fiscal austerity on a nation that is struggling to generate private spending growth sufficient to provide ample employment growth. Once again, the myopia of fiscal austerity is staggering. What does the British government think that British society is going to look like in 20 years when its future adults are being excoriated by the lack of opportunity that the government policy is creating as a deliberate act? Collapsing youth employment rates mean that this cohort is being excluded from the activities which promote stability both in individual terms (self esteem etc) and societal terms. Societies that indulge in this sort of exclusion will rue the day.

There is a related News Release – which summarises the findings. The Report shows that between 1992 and 2004, “young people not in full-time education had an employment rate similar to those aged 25 to 64, but since then it has declined faster”.

ONS say that in the first quarter 2004:

… there was a gap of just 0.2 percentage points between the employment rate of 25 to 64-year-olds (75.5 per cent) and that of 16 to 24-year-olds not in full-time education (75.3 per cent). By October-December 2011, the rate for the older age group was little different, at 74.9 per cent, but the rate for the younger group had declined to 66.0 per cent, meaning the gap had widened to 8.9 percentage points. Over the same period, the employment rate for those 16 to 24-year-olds still in full-time education declined from 38.7 per cent to 27.2 per cent. Overall, in October-December 2011, 3.6 million people aged 16 to 24 were employed, or one in every two young people.

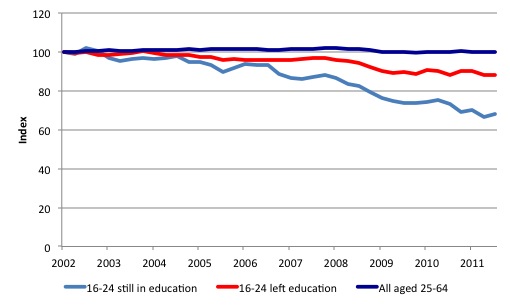

The following graph (using ONS data from the above-mentioned report) shows the change in employment rates since the second-quarter 2002 for the three cohorts in index number form (so May 2002 = 100).

I went back to the second-quarter 2002 because the employment rates were the same (74.9 per cent) for the 16-24 year old cohort who had left education and the 25-64 year old cohort in general. Those people of 16-24 years old in full-time education had an employment rate in that quarter of 40 per cent.

By the last quarter 2011, the employment rates of the 16-24 year olds in education had fallen to 40 per cent. The employment rate for the 16-24 year olds not in education had fallen to 66 per cent while the rest of the workforce had employment rates equal to 74.9 per cent – that is, unchanged from their level some 9 years earlier.

In that time, the recession has exacted a major toll on the British economy and it seems that the burden is being borne by the younger workers.

The decline in opportunities for the youth of Britain is stark.

The UK Guardian article (February 29, 2012) covering the data release – Youth employment rate slumps – said that:

It is important to note that the decline in youth employment rates started long before the recession. As thinktank the Work Foundation points out, the drop began from 2004 – and although economic recovery should help improve youth employment rates to some extent there are deeper problems: namely, young people lacking the experience employers now seek and struggling to get that experience.

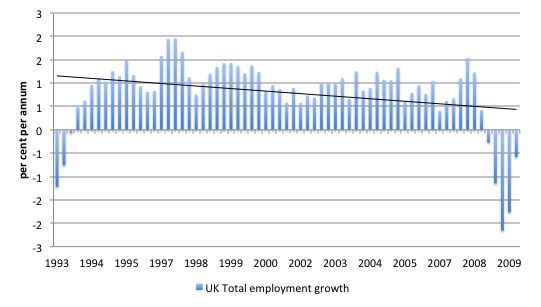

The following graph taken from ONS Labour Force data shows total employment growth in Britan from the second-quarter 1993 to the fourth-quarter 2011. The black line is a simple linear trend.

While the crisis hit in 2008, employment growth was already declining prior to that. From 2003, this rate of decline was accelerating and the first casualities of the reduced growth in employment opportunities was clearly the youth of Britain.

So the “experience” argument has less explanatory power going into the recession than it might have in the period ahead as old capital disappears and new capital is introduced once growth resumes.

This is the classic problem of hysteresis where the skill set that was relevant prior to a recession becomes less so in the next growth phase. But what this emphasises is the need to ensure that workers retain an attachment to paid work so that their more general skills do not atrophy.

That is one of the advantages of having a Job Guarantee. It allows workers to remain engaged with the active labour market while job opportunities elsewhere are scarce.

The British government should be doing all they can to provide paid-work opportunities with training ladders for their 16-24 year olds. Otherwise, they will be disadvantaged for an extended period – that is, the rest of their adult lives.

The solution that the neo-liberals typically propose – which comes straight out of the mainstream economics textbooks is that youth wages have to be cut in order to make them attractive to employers again.

The claim is that younger workers at lower productivity and therefore firms will not employ them if the wages are out of kilter with their potential contribution to production.

The OECD has been a central institution providing succour to this view. For example, in their 2009 report Jobs for Youth: Australia – there is a strong push for cutting youth wages to prevent them from becoming long-term unemployed.

Chapter 3 Demand-Side Opportunities and Barriers with subsections “Starting Wages and Labour Relations” and another “Non-Wage Costs and Other Barriers to Employment” argues that:

Although education and training policies are central elements of any long-term effective strategy for improving youth labour market prospects, a comprehensive policy framework has to pay attention to the opportunities and constraints on the labour market. It must pay particular attention to the labour market arrangements and institutions and their impact on the demand for young people, particularly those with no or limited education or lacking labour market experience … Care should be taken to avoid discouraging bargaining at the workplace level and pricing low-skilled youth out of entry-level jobs … [and in the context of individual contracts] … increased the labour market competitiveness of low-skilled youth.

However, these claims are in denial of what generates the unemployment. If firms were profitably employing teenagers at existing wage levels when demand was strong for their products and they lay these workers off when demand weakens (without a change in wage levels), then it is hard to implicate wage rates in the decision to lay off the workers.

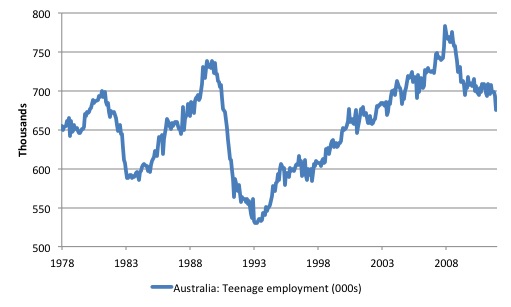

The following graph uses ABS data an shows teenage employment from February 1978 to January 2012 in Australia. Note I have started this scale at 500 thousand deliberately highlight the cyclical events.

Australia had very severe recessions 1982 and 1991 when teenagers, among other disadvantaged groups, in due disproportion losses in employment. In the current period, while the recession has been less severe, teenagers have once again shared employment disproportionately.

I’ve highlighted this impact on the teenage labour force in several blogs – most recently – Age discrimination against our teenagers should end.

The point is that when these cyclical events occur we can detect no sudden change in wage levels and wage relativities. It is very difficult, therefore, to conclude that the rising youth unemployment has anything to do with their wage levels.

The same is observed in terms of welfare support, another neo-liberal target when things get tough. mainstream economists regularly have claimed that persistent unemployment is due to excessively generous welfare support. The OECD has also led the charge in its prosecution of this claim.

The facts are clear – it is difficult, if not impossible, to detect any relationship between changing welfare support levels and the dynamics of unemployment. When unemployment has risen sharply there have been no significant changes in this welfare support levels in any country for which credible data exists.

The collapsing teenage labour market is being driven by failure of the economy to produce enough jobs and has very little to do with wage levels. Before aggregate spending collapsed, firms obviously were profitably employing teenagers (and others) at the prevailing wage levels and relativities. The only thing that changed was total spending.

When aggregate demand is insufficient to full employment the willing labour force, then firms ration their jobs according to various personal characteristics of the available labour supply.

Typically, it will be teenagers, older workers; females; workers of ethnic origin, the disabled, the indigenous etc who suffer disproportionate damage in a recession and are the last in the queue when the growth returns.

When employment growth is insufficient then the most disadvantaged workers are always shuffled to the back of the queue.

The problem is a lack of jobs caused by a lack of total spending rather than excessive wage levels.

The OECD also suggests that that teenage disadvantage is overstated. In response to the observation that teenagers are often cycled between unemployment and casual and part-time work, the OECD assert that the unemployment is “search behaviour” (teenagers don’t have experience with the labour market and have to spend time accumulating knowledge) and the casual and low-wage work is typically a “stepping stone” to better-paid careers

However, the evidence for the “stepping stone” claim is very tenuous at best.

Human capital (HC) theory, a central pillar of neo-classical microeconomics since the 1960s, argues that the outcomes of education and training are embodied in the individual influencing both labour market participation and productivity differences. Wage differentials then relate to the investment decisions made by individuals about their own capacity development.

Closely linked is job search theory, which constructs job search behaviour as the activity of individuals who are deemed to be rational, maximising agents. Accordingly, any labour market participation, including unemployment and casual work, is considered a productive activity in the context of expanding the information required for individuals to make career advancement.

According to this view, the search for work involves the worker continually testing the market for his/her real value which generates a feedback loop whereby the market information and the workers perception of her real value (embodied in the reservation wage) interact to condition the decision making.

Search involves time. HC theory suggests that job search is triggered by the prospect of finding a job or – in case of on-the-job search – finding a better one.

HC and job search theory constructs a notion of poorly paid and precarious casual work as being a paid vehicle for individuals to gain work experience and information necessary to improve their career prospects. In this context, job search (whether from a state of unemployment or within a casual job) is an investment activity which provides the person with the opportunity to escape from the bottom of the labour market.

HC theory also suggests that variations in the non-pecuniary characteristics of employment provide market signals which compel the employer to offer extra pay to compensate workers for the bad job characteristics.

Precarious casual employment, other things equal should be rewarded more fully than secure employment. Neo-classical time-use theory also suggests that workers trade-off various competing activities to maximise their real incomes.

In this context, casual employment is seen as being of benefit to both employers and employees because it allows increased flexibility to combine work and family commitments.

However, the empirical reality would seem to contradict the orthodox construction of casual employment as being a path to better things. First, entrenched casual employment for many is a vicious cycle of disadvantage.

Casual workers receive reduced entitlements, inferior training opportunities, poor working conditions (diminished quality of occupational health and safety) and become trapped. The idea that poor work conditions are compensated for by higher pay does not accord with the reality of the labour market.

Further, the studies that find favourable transitions from casual work link the work to full-time study. The trick is that the students who work part-time in the Fast Foods Industry while studying do get jobs when they enter the labour market on a full-time basis.

But they become engineers or doctors or whatever it is that they studied for. The favourable transition is due to the avantages that a superior level of education brings and is not related to their casual work.

I have done a fair bit of work on this question over the years. Recently we found that (a) highly casualised industries trap casual workers in casual employment as predicted by dual labour market theory; (b) larger firms provide greater social networks for casual workers to transit to non-casual employment; (c) unfavourable local labour market conditions do not appear to intensify the role of signalling in hiring decisions; (d) employment rich metropolitan labour markets enhance the transition rate towards non-casual employment; and (e) once we control for non-individual factors, individual characteristics have little influence on the transition rate.

The OECD clearly prefer the “market” decide on the entry level pay rates. In a sophisticated society, the community through its government and related institutions should decide those things upon the basis of what it wants the minimum entry level standard of living to be.

Then firms have to adapt to that and if they cannot offer employment at those rates then they should not be in business. The market will drive wages down always – in a race to the bottom.

The dynamics introduced during the so-called market liberalisation period were all “low pay and low productivity” and provided no incentives for workers to invest in productive skill augmentation nor firms to invest in high productivity capital. As a so-called clever society it was (and is) a very dumb route to follow.

All of this resonates with yesterday’s UK Guardian article (February 29, 2012) – Ireland’s EU referendum can strike a blow against ‘austerity’ – by one Michael Burke. He went to the heart of the matter.

The article was about the opportunity the Irish people have to reject the austerity policies being forced upon them by the EU (via its own government) at the upcoming referendum on the “fiscal compact”.

One might say that if the Irish support the referendum then they deserve all they are get which will be extended misery. But that might be unkind given the way the elites dominate the media and distort the nature of elections. For example, will the Irish really know what they are voting about – for and against? I doubt it.

But Michael Burke pretty well hit the proverbial nail on the head when he described austerity as:

… nothing other than a transfer of incomes from labour and the poor to capital and the rich … the profit share of national income has risen. This is why stock markets are rising – corporate incomes (profits) are rising. In some cases, such as Ireland, the total level of profits is rising, even while household incomes are declining and the slump in business investment actually exceeds the total contraction in GDP … in return for bailing out Greece’s creditors, the troika of EU, ECB and IMF insist only on more austerity, that is, more transfer of incomes from labour to capital. The treaty provides a clampdown on “structural deficits” whose nebulous existence allows unelected technocrats to impose any cuts they can get away with. Of course this will apply to all countries adopting the treaty. In this way, “austerity” will become the norm in the core as well as the periphery.

Policies like cutting wages and employee benefits are always wheeled out by the conservatives (neo-liberals) during recessions.

These proposals, which deny the obvious fact that the rise in unemployment is due to a collapse in aggregate spending, just seek to ratchet the claim on national income in favour of capital.

The elites know that when growth resumes, the distributional balance between wages and profits will be further skewed in favour of the latter than would have been the case otherwise.

So under the cloak of recession despair they propose policies that will accelerate their cause.

Keynes made an interesting observation in this regard. He said that workers would resist a cut in their real wages engineered through a cut in the nominal wage rates because they knew that when growth resumed their relative position in the wage structure would be impaired.

They would accept a real wage cut that resulted from a general increase in prices because they knew that this would impact proportionately across the wage structure. I will write about the influence of relative wage considerations in another blog. Recognising the importance of these relativities is essential component of sociology. Unfortunately, my own profession chooses, mostly, to ignore their importance.

This redistribution of national income has also provided the financial markets with the gambling chips that eventually brought the world to crisis in 2007. As an academic I’m used to being accused of being unproductive. Apparently we don’t do very much and sit around drinking cups of tea and pontificating about world affairs. Then we put our hands out to “eat the kill” that someone else has produced.

I’ve always been amused by that perception of academic work given that much of the knowledge that defines progress (including technological breakthroughs, medical discoveries, etc) comes from academic research and we provide education, which leads to higher forms of existence (mostly).

I also think it’s ironic that the loudest voices supporting fiscal austerity often come from the financial markets that benefited the most from the neo-liberal era of deregulation.

Apparently, these characters think they “eat what they kill”, which is shorthand in their rather puerile language for being out there on the production coalface, taking chances and enjoying the rewards. According to them, this is exactly the opposite to what they think academics do.

The problem with this perception is that the financial markets are largely unproductive (that is they produce nothing) and they are better seen as being destructive parasites on the system of real income generation.

As to the Irish referendum, I concur with Michael Burke’s conclusion:

If Irish voters do reject the treaty, they will be performing a great service to the population of Europe.

Eventually electorates across the World have to reject the neo-liberal approach to policy. The elites will run riot unless there is a popular uprising. That is better done via peaceful processes but history tells us that the alternative is often the way citizens regain their rights and a semblance of contact with power.

W.B. Yeats an Irish author, poet and playwright (a Nobel Prize winner in Literature in 1923) said to the Irish Seanad Éireann (Senate) during the famous debates on whether to outlaw divorce in 1925 (Source):

I think it is tragic that within three years of this country gaining its independence we should be discussing a measure which a minority of this nation considers to be grossly oppressive. I am proud to consider myself a typical man of that minority. We against whom you have done this thing, are no petty people. We are one of the great stocks of Europe. We are the people of Burke; we are the people of Grattan; we are the people of Swift, the people of Emmet, the people of Parnell. We have created the most of the modern literature of this country. We have created the best of its political intelligence. Yet I do not altogether regret what has happened. I shall be able to find out, if not I, my children will be able to find out whether we have lost our stamina or not. You have defined our position and have given us a popular following. If we have not lost our stamina then your victory will be brief, and your defeat final, and when it comes this nation may be transformed.

Now is the time for the Irish to show it!

Conclusion

The wage cut agenda is one of the usual agendas that the neo-liberals wheel out when there are recessions. But we should see this agenda for what it is – taking advantage of a bad situation to further entrench the hold of the elites on real national income.

I have to catch a flight now as I have commitments elsewhere … so …

That is enough for today!

Fascinating, as usual. The financial class seems to think that their risk-taking at the zero-sum roulette wheel gives them the cache of entrepreneurs. It is the stronghold of Ayn Rand. But it takes more than risk to generate productivity, let alone innovation, as any academic can tell you.

I agree with the premise (and title) namely that societies that exclude their youth will rue the day. In addition to lost productivity (personal and societal) there is alienation of a form so strong it will provide fertile grounds for crime and even revolution. This is not to imply that the last, revolution, is necessarily a crime.

My children (twins) are in that exact cohort (both just entered first year university and work part time in a fast food places) which will feel the full pains of the coming age of problems. I happen to be in that cohort (mature age made redundant) which also feels a sense of alienation from the current system. It is difficult for me to put myself in my kids’ heads nor do I overtly introduce talk of alientation for concern about projection and suggestion. I am careful not to dent their (relative) youthful optimism.

Personally, having seen and experienced first hand and also researched the methods and effects of late stage capitalism on people and the environment I can say advisedly that the total collapse and destruction of capitalism is now the only possible outcome (due to both internal contradictions and environmental destruction). If MMT can be used to provide a transition path to something better it could be helpful. But we have to remember that capitalism can never be reformed. It must perforce be left behind as an acquisitive and destructive system; ultimately maladaptive in all its forms. We will have no choice anyway as it will destroy (almost has destroyed) the world’s entire resource base, lay waste to its carrying capacity and entirely compromise the current “holocene benigity” of the biosphere. New ways will be forced upon the tiny remnants of humanity.

“Virtues / Are forced upon us by our impudent crimes.” – T.S. Eliot

I’m sure Cameron et al have their bolt holes arranged already.

As for the Irish,it will be interesting to see if they display more stomach than the Greeks,except for the small minority of protestors.It appears that the Irish,especially the youth,are indulging in their usual escape route of emigration instead of staying for the fight. And I say this as a person of Irish extraction,admittedly going back to 1863.

Bill

When the youths start rioting this summer, which they will, all the press will run the usual headlines of “how have we come to this’ and feral youths rampage”. The exact whys and wherefores are right here in this article.

It is not often I find myself agreeing with mass murderers but I hope the Irish reject their EU slave masters. My only caveat to that is Ireland will need another bail out when austerity fails. It will be the UK paying that (to protect our banks) if Ireland is out of the Euro.

bill40 – Ignoring your characterisation of Irish people as “mass murderers”, they (the Irish) would not need ‘bailouts’ (when is a loan a bailout?) if they rejected the Euro and grabbed back their own fiat currency. Tough, you bet but at least they would have destiny in their own hands not those of the Troika!

“The elites know that when growth resumes, the distributional balance between wages and profits will be further skewed in favour of the latter than would have been the case otherwise.”

I think the resumption of growth is far from certain, for reasons that extend beyond the purely economic realm.

The pursuit of growth for growth’s sake should be questioned in the same way that MMT questions the neoliberal obsession with budget surpluses. The external costs and distributional consequences of growth must be adequately addressed if we are ever to learn to live harmoniously within the constraints of our biosphere. One day, I hope to see MMT grafted on to a form of ecologically conscious economics that has a deep understanding of human-biosphere relations at it’s heart. Unfortunately, we seem destined for collective ruin before any enlightenment arrives.

George Papandreou, in the last general election in Greece, campaigned on the slogan “The money is there!” – meaning that the warnings about a coming debt crisis issued by the outgoing, conservative government were false. George Gideon Oliver Osborne keeps issuing, now, warnings that there is no money left in Britain’s coffers – meaning that the spending cuts must continue and austerity must prevail. Both men are liars.

Greece, being a country with a foreign currency and little fiscal discretionary authority beyond collecting taxes, does not “have money”. Britain, with its fiscal and monetary sovereignty intact, does “have money.”

I posted this in the Huffington Post today:

I want to address the big lie in the economy which is the root cause of all unnecessary misery.

The household budget is:

(1). (Income = expenses + savings), applies to businesses, individuals, states that are users of money in USA and, the Euro nations.

The national budget is different:

(Federal Deficits = Net Private Savings+ net imports), applies to USA and other nations that have their own currencies and create money.

(2). (G – T) = (S – I) – (X -M), with the notation

Federal deficit = Spending – Tax = (G – T),

Net imports = import-export = (M – X),

Net Private Savings = savings – investments = (S – I).

It is wrong to talk about national budgets in terms of household budgets. If you sum equation (2) over all years we get the cumulative result,

(3) national debt = national wealth, because net imports also adds to wealth. A numerical verification of this is given in

http://pshakkottai.wordpress.com/2012/02/27/national-debt-and-national-wealth-compared/

Hello Bill,

It’s true that over here in Europe, the future looks pretty bleak if not catastrophic. So I guess, like other people (there was recently a special issue of Courrier International on this subject), I am whimsically considering moving to another country. So I started to ask myself: what country is anywhere close to implementing MMT? And the only country that I could find so far was…Argentina. But there is very little literature about the economic miracle that is taking place there. So what do you say? What countries are currently implementing MMT? Is Argentina one of them?

Cheers from Paris

Yanai

@Yanai

There is no country that is “implementing MMT”, since (a) MMT is not a prescriptive approach per se, and (b) no country in the western world would be caught dead admitting its policies are based on MMT analysis. Many countries have formulated some aspects of their policies based on it, knowingly or (mostly) not. When, for instance, Bernanke drops the broad hint that “We [the Fed] did all we could do”, he means that QE isn’t doing much and net-deficit spending, which falls within Congressional authority, is required. Treacherous, dangerous, MMT talk that – though in code.

Cheers.

neilT

I was not referring to Irish people in general, I was referring to one individual who opposes the Troika. I also think that unless Ireland is bailed out again in April it be be bankrupd by using a foreign currency. The UK cannot let Ireland go bankrupt.

@Vassilis

Thanks for your reply. Obviously MMT is a theoretical framework. But it has very concrete implications. For one thing, I think it implies the Central Bank should buy Government debt, not the markets. Are there countries that do that nowadays? If so, what are these countries? Autralia? No. The US? No (even if the Fed hints at MMT sometimes). Is there any place in the world, with some measure of success, where economic policy is conducted with a thorough understanding of a fiat currency workings?

Dear Yanai ,

Try Japan.

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=16101

Cheers.