I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

When anything better than outright recession is regarded as a triumph

I have very little free time today (to write my blog) but several readers have E-mailed me over night suggesting that the British National Accounts data release from the Office of National Statistics indicates that the fiscal austerity is not having as bad an effect on the British economy as I might have suggested. It is a fair question (challenge) and so I will use my limited time to respond to it while the data is fresh. The short answer is this – while the results might have surprised the so-called pundits – the underlying forward-looking message is not optimistic. The data shows that the British economy was growing (3 months ago) but that growth was slowing dramatically and the impacts of the government spending cutbacks were not being felt. All the current indicators are poor. Feeling pleased about the National Accounts data release yesterday seems to be a case of low being considered high. I suppose pleasure should always be taken from small mercies. But I suspect that pleasure will turn sour in the months ahead.

As an aside, the UK Office of National Statistics previously had one of the worst data access home pages of all the national statistics. Who could have ever designed their portal and the way the data was presented is anyone’s guess. Recently they made much of the fact that they had an all improved portal which would make it much easier for researchers to find and access data. The initial impression was that the site was an improvement but that was only in relative to how bad the site was prior to its make-over.

But I have to say the site still leaves a lot to desire and doesn’t offer a very intuitive path to the data.

When considering National Accounts releases, we should always remember that the data only presents a rear-vision mirror view of where the economy has been rather than where it is now and where it is going. The practice of publishing preliminary estimates – which only show part of the full accounts – improves on the lag but leaves people like me to wonder how much revision will be made when the full estimates will be published.

I am always in two minds. The Australian Bureau of Statistics does not publish preliminary estimates but does publish a sequence of related releases (of the components of the accounts) prior to the final release. But we have to wait until early December to get the third quarter GDP data.

So the British choice to publish data for July-August-September in early November does provides some information about the production sector in advance of the full information on the expenditure and income components which will come later. I don’t know for certain which system of publication I prefer – there is pro and con with both. I probably lean to the practice of publishing flash or preliminary estimates.

Anyway, what did these preliminary estimates tell us about the British economy three months ago?

The headlines I initially read told us that George Osborne would be very happy with the National Accounts data release as if an annual growth rate of 0.5 per cent was a cause for celebration. How low can our sense of achievement go?

Much of the “euphoria” was based on the fact that the bank economists had forecast an even lower figure.

But closer examination shows that the data release – especially given it is “old” data – suggest that the British economy is faltering badly and will deteriorate further as the impacts of the government fiscal austerity cuts really start to impact in the coming months.

The first reason for caution is given by the Office of National Statistics itself:

The interpretation of the estimate for Q3 is complicated by the special events in Q2 (for example, the additional bank holiday in April for the royal wedding), which are likely to have depressed activity in that quarter. As with 2010 Q4 and 2011 Q1 (affected by the bad weather in Q4) it may be wise to look at 2011 Q2 and 2011 Q3 together, rather than separately. On that basis GDP has grown by 0.6 per cent in the last two quarters and by 0.5 per cent in the last year.

So caution is warranted.

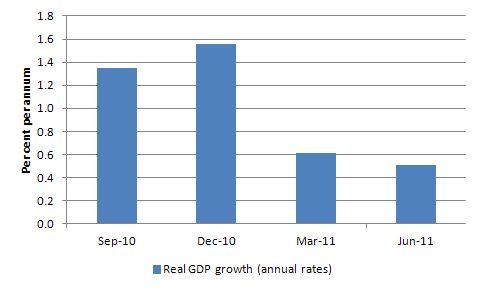

The following graph shows the annual real GDP growth rates over the last four quarters. The evidence clearly shows the British economy is slowing.

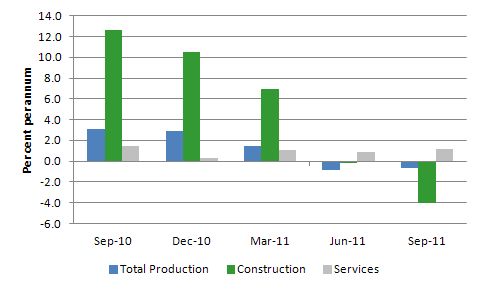

The following graph shows the broad sectoral breakdown of the real GDP growth over the last four quarters. Only services is driving growth at present with construction plunging into negative territory after driving growth (courtesy of the fiscal stimulus) in 2010.

The growth is also being driven by the services sector (mainly) and the ONS reports that “Government and other services increased by 1.4 per cent between 2011 Q3 and 2010 Q3” while within services – “Health and education made the largest positive contributions to the quarterly increase”.

What does that tell us? Quite simply that the fiscal austerity packages are yet to feed through. Once the government cuts emerge then this source of growth will disappear and will feedback further in a negative way on private confidence.

The problems in Europe will also eventually impact negatively on exports.

The UK Guardian Economics blog (November 1, 2011) – UK economy swiftly running out of growth sectors considered the significant contraction in Construction and concluded that:

Whichever way the figures add up, it’s not a positive result. The same can be said of manufacturing, which was supposed to lead the country out of recession as part of a re-balancing away from sectors like construction. However, manufacturing was subdued and extra spending on gas and electricity following huge energy price hikes accounted for most of the growth in “production industries” … Looking back over the full year, the ONS says growth was 0.5%, or 0.125% in each quarter, which is likely to be the weakest of any eurozone country except Greece and well below US growth of 2.5%.

So with the cuts foreshadowed for the government sector not yet impacting in the third quarter 2011, the weakness in the British economy is mostly due to very weak private spending. Indeed, exports seem to have risen relative to 2010 (we will need to wait for the final expenditure estimates to know the complete export picture).

Another UK Guardian commentator – Michael Burke (November 1, 2011) – Good GDP data? No, the economy’s stagnant and Europe can’t be blamed – successfully argued that the British malaise cannot be blamed on recent events in Europe which will impact more fully in the fourth quarter 2011:

This effort to portray Europe as the source of the British economic crisis is wholly misplaced. Despite the crisis, countries such as Germany and France have nearly recovered the entire level of output lost in the recession, yet the British economy remains way below its pre-recession level, even after the latest quarterly growth. It is the British economy that is a drag on Europe, not vice versa.

If there were any impact now on the British economy from the crisis of the euro area then it would be seen first in the trade data – exports would be declining. Instead, in July and August of this year (the latest available data that will comprise part of the Q3 GDP data) British exports rose strongly, up nearly 16% compared to the same two months in 2010.

Just because government spending contributed to real GDP growth in the third quarter 2011, one cannot validly conclude that the fiscal austerity program has not had a negative effect on growth. The conclusion from the National Accounts release is obvious – the declining real GDP growth rate was the result of a very pessimistic private sector.

My assessment is that the consumers and firms have been totally spooked by the rising unemployment and the impending spending cuts (and the actual loss of public sector jobs). All the private confidence indicators are pointing downwards.

Keynes pointed out long ago that one role for government fiscal stimulus was to provide spending support to an ailing economy. But in doing so it could engender a renewed private optimism which would lead to a private spending recovery.

I concurred with the conclusion of Michael Burke – which inspired the title of my blog today:

When is economic stagnation a cause for celebration? When the economic outlook is so bleak that anything better than outright recession is regarded as a triumph.

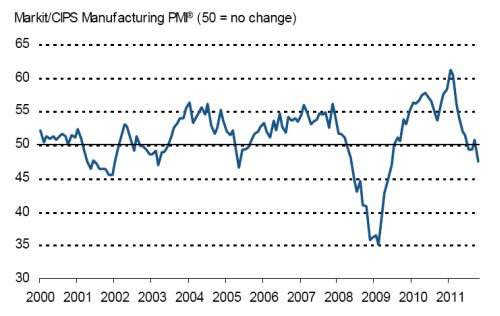

More current information is available from the Markit/CIPS UK Manufacturing PMI which was also published yesterday (November 1, 2011). The PMI refers to the Purchasing Managers’ Index which are the product of monthly surveys of business conditions. They are very current and probe the conditions at the firm level.

The PMI is a “diffusion index” and Markit say that “For each of the indicators the ‘Report’ shows the percentage reporting each response, the net difference between the number of higher/better responses and lower/worse responses, and the ‘diffusion’ index … An index reading above 50 indicates an overall increase in that variable, below 50 an overall decrease”.

The headline in the current Market PMI was:

UK Manufacturing PMI hits 28-month low in October as output, new orders and employment decline

The following graph is taken from the Markit publication. You can see that the index is now below 50 which indicates an overall decrease. The PMI has regularly crossed into negative territory (below 50) in the last decade as is evident and so it is too early to conclude that the series is heading the same way as it was in 2008.

But with Europe now in a total shambles courtesy of its political leadership compounding the deficiencies of the design of its monetary system and the British government’s austerity package still yet to fully impact it is reasonable to conjecture that an early recovery for manufacturing is less likely.

Markit summarises that facts in this way:

– UK Manufacturing PMI at 47.4 in October, down from 50.8 in September

– Substantial reduction in new order inflows

– Inflationary pressures eases, as input costs and output prices rise at slower rates

The data “signalled a deterioration in overall operating conditions in three of the past four months” and that “Manufacturing production declined for the second time in the past three months in October, as companies scaled back output in response to reduced inflows of new business”.

For those (the Government etc) who are claiming that recovery will be driven by exports growth the Survey provides some sobering data.

Companies reported weaker demand from both domestic and export markets. The level of incoming new export orders fell for the third month running … Reduced order inflows were received from clients in mainland Europe, Asia and the US. The latest reduction was partly linked to clients delaying purchases or destocking in response to the deteriorating global economic backdrop.

The official commentary from Markit said that “(t)he most worrying aspect of the survey is the trend in new orders, which declined at the quickest pace since March 2009” and further that “We live in worrying times. The manufacturing sector, which helped to keep growth buoyant earlier in the year, is now struggling to keep its head above water … Confidence is being hit hard as the sector feels pressure from all angles”.

This sort of data is the reason why most informed commentators are estimating the the GDP growth figures for the fourth quarter 2011 will show continued deterioration on the trend already evident. The only question appears to be whether the British economy will plunge into negative growth or continue to asymptote towards the zero growth line. It was already close to that in the third-quarter as is evident from yesterday’s preliminary National Accounts release.

The British Prime Minister recently wrote a self-congratulatory piece in the Financial Times (October 30, 2011) – A three-pronged plan to revive Britain’s economy where he claimed that the fiscal austerity strategy that the British government adopted is working.

The evidence he provided to justify his conclusion was very sparse. But he did say this:

Those who still argue for an abandonment of our deficit reduction plan should reflect on the journey this country has taken. We went into the bust with the biggest structural deficit in the G7 and came out of it with a deficit forecast to be the biggest in the G20. It is thanks to the credible plan this government has set out that today we have market interest rates of just 2.5 per cent – half what they are in Spain or Italy.

If you consult government bond yields you will find that the comparison between the United Kingdom and other sovereign nations (those that issue their own floating currency) does not substantiate the Prime Minister’s case. There is nothing exceptional about British interest rates.

The comparison with Spain or Italy is not valid given they operate in a different monetary system (EMU) where these nations do not have their own currency.

Further, Japan has a much larger deficit relative to GDP than the UK and clearly the highest public debt (as a percentage of GDP) of any nation. Their interest rates have been around zero (10-year bond yield is about 1 per cent at present) for two decades.

The demand for British government bonds remains strong and did not look fragile at all when the previous government introduced their fiscal expansion which finally kick-started growth. That growth is now evaporating.

The National Accounts data that came out yesterday in Britain certainly doesn’t support the Prime Minister’s claim that his fiscal austerity approach is building on the growth that was engendered by the fiscal stimulus.

Greek referendum

Greece founded the concept of democracy – in Ancient Athens sometime around 508 BC. So they have had a long engagement with the concept notwithstanding the interventions of military dictatorships from time to time.

The Greek government’s decision to have a plebiscite about the latest (very harsh) austerity packages that the Troika is imposing on the nation has unsettled the financial markets. While I will write more about this in the future the decision is clearly an improvement on the way the oligarchy in Greece has been dealing with its people.

If the Greek population go along with the austerity package by voting in favour at the plebiscite then an outsider like me can hardly keep arguing that the people have been denied a voice.

I realise that the conservative media and vested interests will distort the public information available to bias the vote towards supporting the austerity package. I realise that few people will fully grasp the reasons that Greece is in the state it finds itself and will not fully grasp that the problem is the Euro itself and to eliminate the problem requires an exit from the European Monetary System.

In that sense I understand that the outcome of the plebiscite may not send a clean signal of the informed preferences of the wider Greek population.

When I advocate an exit from the Euro I an not naive to the fact that an exit would be extremely costly and the costs would endure for years to come and probably punish the less advantaged members of the population disproportionately. I realise that essential stores like medical supplies, energy and food etc would be in short supply. They are already!

But I judge that the net impact over the next decade will be better for all especially the poor if Greece exits and introduces its own currency.

I hope the people vote to reject the interventions of the Troika and push to eliminate the Euro and restore currency sovereignty.

Conclusion

I repeat Michael Burke – “When is economic stagnation a cause for celebration? When the economic outlook is so bleak that anything better than outright recession is regarded as a triumph”

A day full of meetings and commitments is now ahead – so I have to cut this short.

That is enough for today!

“The demand for British government bonds remains strong”

That’s hardly surprising given that excess demand is built into the Quantitative Easing mechanism. Banks use the QE money to buy gilts so that the Debt Manangement Office can pay the interest on the £200bn+ of Gilts held at the Bank of England.

Which then sits on that money. Over £8bn a year or about 2% of GDP.

I certainly hope the ‘monetary stimulus’ generated by this design is greater than that, but I suspect it isn’t.

Q2 Sectoral balances in the UK (which finally turned up last week) show that the external sector net-lending fell to 0.28% of GDP down from over 2.3% at the end of last year and that private businesses increased their investment by 1.2% of GDP.

Financial sector and household sector net saving was up though (and I think the Bank of England falls into the private financial sector on these statistics).

Overall that means that the government deficit in the first half of the year fell by 1% of GDP.

Of course we won’t see the Q3 sectoral figures this side of Christmas, but it’ll be interesting to see if the private fixed capital formation levels continue or not. I can only think that is forced replacement as there’s not really that much to invest for in the UK at the moment.

The fact that Britain has not enjoyed strong export-based recovery despite 30% devaluation of the pound against euro supports my view that this export-led strategy fundamentally misses simple accounting identity explained here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balance_of_payments, that in absense of reserve or capital account deficits there cannot be surplus in the current account, and that is what export-led growth is all about; gaining claims on foreigners.

And “breaking free from the euro” should not be so difficult as everyone presumes, as far as I can tell there is nothing prohibiting individual states starting to make payments in a new currency, it would require some technical arrangements, as well as mandating taxpayers to pay some proportion of their taxes in this currency. Euro debts are promised to be paid back in euros, why broke that promise? Anyone holding local currency could go to the FX markets to get some euros to pay back euro-nominated debts, as it is case with any other currency. New, local currency could replace euro as currency of use and euro debts could be paid back slowly over long periods of time.

About Greece, people seem to think it will be much worse off. Honestly, the more I read Greece’s data, the less I can think so.

If that troika plan is accepted, public debt will be at 120% by 2020! Those are long years of austerity, specially if we consider European Union’s targets as 60% public debt!

Bill – start the day with a smile: HARVARD & THE MANKIW REVOLT

Cheers …

jrbarch

“I have very little free time today…”. When I read this, I thought “awesome, finally I’ll be able to read all the article”. So, I scrolled down and I recognized the article is as long as any article Bill wrote when he has a lot of free time; please,don’t give me false expectation anymore. Now I feel depressed.

Neil,

“…private businesses increased their investment by 1.2% of GDP.”

According to the BBC, there was a suprise up-lift in construction in October related to commercial construction, and this may have accounted for it (or not) – albeit with a delay before construction started – though the article says that this was not expected to last:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-15552522