I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

It is easy to create jobs

The US President delivered his long-awaited speech outlining the proposed American Jobs Act today to a packed Congress. The room was full of self-serving, anti-intellectuals masquerading as the representatives of the people of America. Eventually, this sham will be clear to all and the “American people” will “demand action”. If they don’t then the neo-liberal domination of policy which has led to the crisis and the extended malaise will continue to impoverish them. Bold action was needed from the President at least to demonstrate leadership so that the democratic forces could start to pressure the T-pots. Unfortunately, the President doesn’t seem to understand that it is easy to create jobs. A government just has have the will to do so.

To start with today, on the Australian national broadcaster – the ABC – this morning there was an expert (a regular finance commentator) talking about his expectations of the Jobs speech. He said something like this (no transcript is available):

Well governments don’t create any jobs directly – they can’t do that – and there is debate about whether they can stimulate the private sector to create jobs. The private sector is the only place that jobs are created.

The irony was that he was being interviewed on our national government broadcast station by presumably public servants (the media journalists). Or don’t they really have jobs?

I suppose the soldiers shooting up Iraq and torturing innocent people were not actually working. I suppose all those politicians are not really paid. I suppose all those teachers that teach in the public system and nurses who work in public hospitals are not voluntary staff.

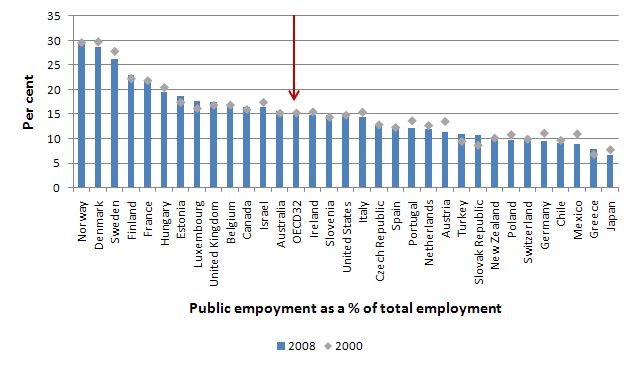

The following graph is taken from the recent OECD Government at a Glance 2011 publication (Chapter 21 – Data). It shows Employment in general government and public corporations as a proportion of total employment for 2000 and 2008.

The red arrow just indicates the OECD average. Around the average is Australia and the US. Note the Scandinavian nations which helps explain why the standards of public education, health and personal care services are so advanced in those nations relative to elsewhere. Note also Greece – which allegedly has a bloated public service – well they must be hiding a lot of public workers in the private sector!

The point is that there are millions of jobs created directly by governments all around the world. We might prefer some of them were not created – like most of the military – but the fact is they are paid a wage by some government or another and spend that wage which enters the macroeconomic expenditure system in exactly the same way as wages paid by private employers manifest – sort of – “Excuse me, can I buy this item please?” “Certainly, that will $X”, “Thank you”.

Why would our national broadcaster have ideological idiots who claim governments do not directly employ people on their program? Fox yes! ABC definitely should not.

How much of a renewed stimulus is required?

The US Congressional Budget Office estimated that the 2010 GDP gap (actual (or projected) GDP minus potential GDP) was -5.7 per cent and the 2011 gap would be around 5.1 per cent. The corresponding unemployment gap (the actual (or projected) rate of unemployment minus the natural rate of unemployment, which is the rate of unemployment arising from all sources except fluctuations in aggregate demand) was 4.6 per cent in 2010 and 4.4 per cent in 2011.

As I explain in these blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! and Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – there are good reasons for believing these estimates understate the true shortfall in aggregate demand.

But taking them on face value (they certainly do not overestimate the scale of the problem) these percentage gaps translate into US dollar terms as a $US884 billion shortfall in aggregate demand in 2010 and a projected $US805 billion shortfall in aggregate demand in 2011.

That gives you some guage against which to measure the American Jobs Plan – which proposes a $US447 billion combination of tax cuts and spending outlays.

In this regard I agree with Paul Krugman’s assessment (September 9, 2011) – Setting Their Hair on Fire – where he says of the “Jobs Plan”:

It calls for about $200 billion in new spending – much of it on things we need in any case, like school repair, transportation networks, and avoiding teacher layoffs – and $240 billion in tax cuts. That may sound like a lot, but it actually isn’t. The lingering effects of the housing bust and the overhang of household debt from the bubble years are creating a roughly $1 trillion per year hole in the U.S. economy, and this plan – which wouldn’t deliver all its benefits in the first year – would fill only part of that hole. And it’s unclear, in particular, how effective the tax cuts would be at boosting spending.

I will reflect more on the US Presiden’t plan next week – after a long journey that awaits me.

But in the last few days, we have seen several “plans” from different economists who recognise that the entrenched high unemployment is the problem despite what you might glean from the behaviour of politicians around the world in the last 12 months.

I provide some brief comments on each of these approaches.

Plan 1 – hope that small business comes good

British academic David Blanchflower announced he had a plan (September 8, 2011) in this article – Here’s my plan for kick-starting Britain. MPC – take note. While this was British-centric, the ideas have universal application.

He wants to solve the crisis with monetary policy:

The Bank of England should come up with a plan for easing access to credit for small businesses.

How? By looking for leadership from the US Federal Reserve which Blanchflower thinks will introduce QE3 in November using an “Operation Twist” tactic which would involve “selling short-dated treasuries and using the proceeds to buy long bonds. The aim is to flatten the yield curve and lower long-term interest rates, which would act as an economic stimulus”.

Please read my blog – Operation twist – then and now – for more discussion on this point.

Earlier in the article he said that given the price of overnight funds is effectively zero in the US the “central bank has little choice other than to raise the quantity of money”.

And in that juxtaposition you find the classic misunderstanding about Quantitative Easing. The first statement is the correct statement. QE can only lower interest rates at investment maturities which of itself does nothing. For there to be an aggregate demand stimulus firms have to desire funds to invest and that desire comes from their expectations of what they can sell with the extra created capacity.

Lowering investment rates at a time that expected project revenues are low (and unprofitable at any rate) will do nothing. And that is why QE has failed in its charter.

The second statement about increasing the “quantity of money” is an erroneous “money multiplier” type scenario where central banks stimulate demand by increasing the liquidity of the banks which allegedly makes it easier for them to lend. QE does nothing of the sort. It increases bank reserves but then banks do not lend reserves. Further, the banks do not have an inability to lend at present. They face a dearth of credit-worthy customers who want to borrow.

Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

Other blogs of relevance are – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary.

The problem of-course is that in conflating these issues you have to consider Blanchflower himself is somewhat confused despite his heart being in the right place – that is, a concern for the devastating unemployment in the advanced world.

But given his bias towards monetary policy his plan rests on the Bank of England engaging in “competitive QE” with the US Federal Reserve:

… to prevent the US gaining an advantage by further depreciating its currency against the pound.

The reality is that QE will not stimulate aggregate demand in the face of fiscal retreats which are dominating the US and British scene at present.

Lower interest rates will not stimulate investment spending when the retail outlook is dismal and getting worse. Firms do not invest in capacity that produces things that cannot be sold at a profit.

Further, the external economy is now deteriorating for most nations and the exchange rate stimulus that might come from depreciation is being cruelled by the income effects as import demand declines. A net export-led growth strategy will also not do the trick.

So Blanchflower’s “suggestion” for the BoE to “… directly fund lending to small business, so-called “credit easing”, rather than carry out further quantitative easing” will in my view not deliver significant growth prospects. It is a supply-side solution (lowering cost of supply) to counter what is almost exclusively a demand-side problem.

At present, there is no shortage of productive capacity (capital or labour) but a shortage of sales. Lowering the cost of finance to small businesses will do very little in that environment.

My conclusion is that the British would be unwise to rely on monetary policy – in this form or any other form – to counter not only the parlous and worsening private demand situation but also the exacerbating fiscal contraction which will gather pace in the coming year (if the British government sticks to its ridiculous plan).

Another plan

Joseph Stiglitz (September 9, 2011) outlined his plan in this article – How to put America back to work – and said that:

You don’t create jobs and growth by firing workers and cutting spending …

Spending equals income which equals output which drives employment and lowers unemployment. Any credible plan has to advocate a large increase in aggregate demand as noted in the introduction.

That is the first pre-requisite for a credible jobs plan.

Stiglitz understands that clearly but then gets lost in some “deficit dove” ennui:

The answer from economics is: There is plenty we can do to create jobs and promote growth.

Yes, it isn’t rocket science. There are millions of jobs out there they just need to be backed with spending – public and/or private.

But, according to Stiglitz:

There are policies that can do this and, over the intermediate to long term, lower the ratio of debt to gross domestic product. There are even things that, if less effective in creating jobs, could also protect the deficit in the short run.

But whether politics allows us to do what we can – and should – do is another matter.

When we are having a civilised discussion about job creation why would someone want to start qualifying it by appealing to irrelevant concepts like the “public debt ratio” and the size of the deficit? If spending can create jobs and you need millions of jobs created then it is clear – more spending is required.

If you define the role of government to advance public purpose and ensure there are enough jobs if the private sector demand for labour is deficient then whatever public debt ratio or budget deficit that transpires is the “correct” one (given current institutional arrangements). For a currency-issuing government, which can never go broke, how much debt it is carrying in its own currency, is irrelevant.

The reason why we get these conflicting signals in this plan is because Joseph Stiglitz is a deficit-dove which means he is part of the problem to some extent.

Please read my blog – When you’ve got friends like this … Part 6 – for more discussion on this point. Deficit doves think deficits are fine as long as you wind them back over the cycle (and offset them with surpluses to average out to zero) and keep the debt ratio in line with the ratio of the real interest rate to output growth.

Deficit doves are within the same species as the “deficit hawks” in that they believe that the long-term deficits pose serious risks although short-term deficits might be necessary during a recession. A standard aspiration for a deficit dove is thus to propose the government runs a “balanced budget” over the business cycle which is clearly dim-witted as a stand-alone goal and un-progressive in philosophy.

But Stiglitz certainly understands that:

Monetary policy, one of the main instruments for managing the macro-economy, has proved ineffective – and will likely continue to be. It’s a delusion to think it can get us out of the mess it helped create. We need to admit it to ourselves.

I admitted it a long-time ago! In fact, I never considered fiscal policy to be the silent partner in the macroeconomic tools.

He also clearly rejects the principal tenet of fiscal austerity – the “fiscal contraction expansion”:

… we must dispose two myths. One is that reducing the deficit will restore the economy. You don’t create jobs and growth by firing workers and cutting spending. The reason that firms with access to capital are not investing and hiring is that there is insufficient demand for their products. Weakening demand – what austerity means – only discourages investment and hiring.

Definitely.

The “second myth” he rejects is:

… that the stimulus didn’t work … The administration did make one big error … it vastly underestimated the severity of the crisis it inherited … Without the stimulus, however, unemployment would have peaked at more than 12 percent.

Compare that to the continued denials by John B. Taylor and co that the stimulus didn’t do a thing. I wonder if their jobs were linked directly to the national unemployment rate – so for every point rise, a random academic economist at Harvard, Chicago or Stanford – lost their job and retirement benefits – whether they would be opposing further stimulus.

Stiglitz then indulges in more deficit-dove arguments about putting the “country on the road of fiscal responsibility” intermixed with “(t)he single most important thing, however, is putting America back to work: Higher incomes mean higher tax revenues”.

The former considerations just undermine the latter aspirations.

His plan then is to:

… to use this opportunity – with remarkably low long-term interest rates – to make long-term investments that America so badly needs in infrastructure, technology and education.

We should focus on investments that both yield high returns and are labor intensive. These complement private investments – they increase private returns and so simultaneously encourage the private sector.

The “low” interest rates do not give the US government more capacity to engage in vast and productive infrastructure investments including hiring more teachers (a policy Stiglitz proposes). The US government could bail every state government out without any financial issues arising – as long as the funds were spent on bringing productive resources (including sacked teachers) back into use.

I agree that the “increased output in the short run and increased growth in the long run can generate more than enough tax revenues to pay the low interest on the debt. The result is that our debt will decrease, our GDP will increase and the debt to GDP ratio will improve” but that should not be the way of selling a renewed and larger fiscal stimulus.

That is the way a deficit-dove talks and ultimately their ideas are self-defeating because they propose balanced budgets over the cycle which means that the private domestic sector balance has to match the external balance on average over the cycle – which means that if there is a external sector deficit there will also be a private domestic deficit (and increasing overall private indebtedness).

You really get the deficit-dove rhetoric in this statement;

No analyst would ever look at just a firm’s debt – he would examine both sides of the balance sheet, assets and liabilities. What I am urging is that we do the same for the U.S. government – and get over deficit fetishism.

Trying to justify increasing government debt by using a firm analogy is as bad as the household-government budget analogy. The firms who raise debt have to to expand their current spending opportunities. They use the currency that the government issues.

The government issues the currency and can spend what it likes and then can borrow back its own spending if it, for some odd reason, desires to do that.

Stiglitz thinks a large public infrastructure investment plan is beyond the political capacity of the US politicians to absorb and so gets even more doveish:

… there is another, not as powerful but still very effective, way of creating jobs. Economists have long seen that simultaneously increasing expenditures and taxes in a balanced way increases GDP. The amount that GDP is increased for every dollar of increased taxes and spending is called the “balanced-budget multiplier.”

There may be reasons why we would want to the government to introduce “well-designed tax increases – focused on upper-income Americans” which would be justified by the desire to deprive them of potential purchasing power for equity reasons. At present there is no aggregate demand pressure on the inflation barrier and so you couldn’t justify increasing taxes as a measure to attenuate nominal demand growth.

I would also introduce (as I advocate in Australia) increased taxes on polluters and mining companies etc. But none of these measures have anything to do with stimulating aggregate demand.

To stimulate aggregate demand either the public and/or the private sector has to increase spending.

It might be the case, as Stiglitz argues that “(i)ncreasing taxes at the top … and lowering taxes at the bottom will lead to more consumption spending” because of difference saving propensities.

But changing the tax mix should be about making it more equitable for a given brake on aggregate demand.

If the lower income earners will spend more if they have more cash then the solution is obvious. But at this point in time with degraded infrastructure and households struggling with debt it would be better to generate jobs for the unemployed directly so that incomes can rise that way and stimulate private saving.

Which leads me to …

The only credible plan

The superior plan is that which my US MMT colleagues – Randy Wray and Stephanie Kelton – outlined in this article (September 8, 2011) – What the Country Needs Is a New New Deal.

Their assessment of Obama’s Plan is that it is:

Too little of what will work and too much of what won’t for an economy that’s teetering on the brink of a double-dip recession and a president who is running out of time to deliver jobs.

The reason for their scepticism is that many aspects of the plan do not “add a single dollar of new demand to the economy” – and this includes extending unemployment benefits and the payroll tax cut.

Neither initiative represents expansionary spending.

They argue that:

The truth is simple and contrary to these views. Business will not hire more workers until it has more sales. Consumers will not spend more until they’ve got more jobs. A private-sector recovery requires 300,000 new jobs every month. But the private sector doesn’t need 300,000 new workers per month to meet prospective sales.

The new jobs can only come from the federal government-the only economic entity that can afford to hire. Obama’s 1 million infrastructure jobs is a nice down payment, but it is only three month’s worth. New workers will create the sales that firms need to justify new hiring. Still, we must think bigger if we are to create 20 million jobs.

I will leave it to you to study their plan – which requires the US Government to introduce a Job Guarantee –

To learn more about the Job Guarantee you might like to review the blogs that this Search String provides

The bottom line is that a “new New Deal is needed, with a comprehensive jobs program to again transform America”.

That takes me back to the beginning – governments directly create employment every day. When the private sector is unwilling to generate jobs then the only sector left to pick up the slack is the government.

There is no doubt that in many of the advanced nations (including Australia) that the private sector is not willing to create enough jobs. The solution is a mass public sector job creation program. That should have been at the top of President Obama’s American Jobs Plan.

Conclusion

I also agree with Paul Krugman that the American polity is so riddled with addled minds that the President’s job plan is likely to receive short shrift. And that:

… Mr. Obama may finally have set the stage for a political debate about job creation. For, in the end, nothing will be done until the American people demand action.

What is required to solve the crisis is a thorough-going re-think of how we run our economies. The neo-liberal years which transferred massive power and real GDP (taken from the workers) to the financial markets and diminished the public oversight of markets has failed.

All of the dimensions of that ideological approach have failed to deliver on their promises.

We need wholesale banking reform – please read the following blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks for further discussion.

We need a major change in the way we consider real wages growth – please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

We need to eschew the notions that budget deficits are evil and see them for what they are – the public mechanism for ensuring there is full employment. In that context, depending what is happening in the other sectors (private domestic and external) these public policy goals might even be accomplished with a budget surplus. The point is that it doesn’t matter – the focus has to move from the “budget balance” which is irrelevant in its own right to the real outcomes – sustainable growth, full employment, etc.

Friday music

Today’s musical segment comes from local Newcastle (NSW)-based swing blues band – The Blues Box – which has some economist in it playing guitar.

We recorded this version of Sonny Boy Williamson’s song – Bye Bye Bird – in a live environment (through a 12-track digital machine) with minimal mixing and effects. Pretty raw in other words. The band swings though.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

I’m afraid that any debate in Washington about putting people back to work will only be a discussion among neo-liberals about the best way to decrease public spending, cut taxes for the corporations, and deregulate.

I read an article in last Sunday’s paper by one of our NC representative in Congress in which she said that the government can’t create jobs and that job creation is the responsibility of the private sector. Naturally she is calling for more business friendly changes. I really don’t know how these people get elected.

Bill, I share your low opinion of Stiglitz. Unfortunately the world is full of people, like Stiglitz, who got a Nobel prize a long time ago for some doubtless good work in particular areas of economics. They now make a living spouting views on areas of the subject about which they clearly know very little.

He didn’t get a Nobel prize. There isn’t a Nobel prize for economics – there is an award from the Bank of Sweden.

Great post Bill.

Here’s an eye-opening piece from Ken Houghton showing that the hard core of the US jobs problem lies in the devastation of state and local governments.

http://www.angrybearblog.com/2011/09/private-sector-employment-in-jobless.html

Dear Bill,

I’m sorry to inform you that most of your recommendations will soon be illegal in Italy and Spain, whose respective legislatures are, as I write this, busy passing constitutional resolutions for mandatory balanced budgets.

What was that old movie title? It’s a mad, mad, mad, mad world.

Italy joins the Tea Party

Spain joins the Tea Party

Dear Vassilis Serafimakis (at 2011/09/09 at 21:38)

Thanks for the T-Pot update. All these idiots are doing is ensuring that social instability will rise and relations will breakdown eventually. 1848 all over again.

Anyone want to storm the EU building with me in Brussels on Monday? We should ring ahead though – we would not want to interrupt some lunch or reception where the EU bosses are dining sumptuously and drinking plenty of wine. They will be discussing serious things I am sure.

best wishes

bill

I fear that we won’t get anywhere until there is significant destruction. Japan has had twenty years in limbo slowly going nowhere.

Perhaps they need to learn the hard way. In some respect total destruction is better than living in purgatory. At least then you can move forward.

The existing priesthood need to be completely and irredeemably discredited. And that is going to be difficult without significant human suffering.

Why are people such damn fools sometimes?

I blame the media for giving authority to these nonsensical neo-liberal ideas and policies, they don’t question them for one second and just repeat the lies again and again like propaganda, the public have been mislead and still don’t seem to realise they’re being conned, the media and political classes are an absolute disgrace, the triumph of mediocrity is the phrase that springs to mind when you see what’s happening.

Bill-

What are your thoughts on the monetarist idea of the Central Bank level targeting nominal GDP? Is there a transmission mechanism that this could work?

Thank you

Does anybody have the info on whether the Eurozone has historically run a deficit as a whole or not?

As we know, a balanced budget leads to recession. Pace a sovereign country, the Eurozone will never prosper unless there are financial transfers from richer to poorer countries. But it will also never prosper unless it runs a (small) deficit over the cycle. And who decides on how many Euros get printed?

Professor Mitchell, you wrote, “I wonder if their jobs were linked directly to the national unemployment rate – so for every point rise, a random academic economist at Harvard, Chicago or Stanford – lost their job and retirement benefits – whether they would be opposing further stimulus.”

It wouldn’t matter. Their beliefs are clearly faith-based, and they’d probably assure themselves that their ideas, which are certainly correct*, will magically transform reality any day now. It is religious thinking, and you don’t want to play chicken (or Russian roulette) with a believer.

* – In their minds, not mine.

Also, nice work on the music. Thanks for sharing that.

“There may be reasons why we would want to the government to introduce “well-designed tax increases – focused on upper-income Americans” which would be justified by the desire to deprive them of potential purchasing power for equity reasons. At present there is no aggregate demand pressure on the inflation barrier and so you couldn’t justify increasing taxes as a measure to attenuate nominal demand growth.”

I think that you underestimate the selective inflationary effects of wealth inequality. The distinction between “purchasing power” of the wealthy and “asset inflation” is unclear. Surplus funds are parked in bonds, in gold, in stock markets — or in speculative investments in commodities such as oil. The inflation of gold prices has no real economic effect, but speculation in stocks affects pension funds, and speculation in commodities takes money out of the pockets of consumers and inhibits aggregate demand. When Google has $30 billion in cash, borrows $4 billion, buys Motorola for $12.5 billion in cash — perhaps plans to buyback its own stock — where is the positive economic effect or these wealth transfers? Do they actually increase production or create jobs?

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/44163683/ns/business-stocks_and_economy/t/google-shows-cash-rich-firms-may-not-need-loan-markets/#.Tmo0H3P7Bic

In the modern highly financialized economy, wealthy individuals and corporations recirculate money within what is effectively a closed system, selectively inflating asset prices. This is true even as most households and businesses are living in a balance-sheet recession in which they must repay debt (save). In the U.S., where government spending passes though the bond market, only taxation redistributes wealth and increases aggregate demand — if taxes are directed toward job creation.

Re the whole ‘public sector cannot create jobs’ mantra, here in Ireland, we hear this repeatedly from our political class. Last Sunday afternoon, on RTÉ (that’s the national broadcaster, funded by TV licence revenue, manadatorily collected), our ‘Enterprise’ minister said the following: “Government can’t create jobs, only enterprise [sic] can create jobs”. He was, of course, immediately laughed at by his radio interlocutor, who went straight to an ad break because he couldn’t continue with the interview.

I jest.

This, of course, is the same Minister who makes himself available at press conferences for the announcement of any ‘potential’ jobs promised by foreign companies setting up here in our low corporation tax regime. The job numbers in most cases are pretty derisory, and in any event, tend to be overestimated, if they materialise at all. The kicker is, that these ‘entrepreneurs’ have promised these jobs having been given ‘support’, i.e., subsidies, by an entity called ‘Enterprise Ireland’, a quango that doles out apparently scarce public money. No-one ever questions this charitable donation to people from the beloved private sector. Bring up the possibility of running a railway line through Dublin Airport, and people are soon whipped up into a rabid frenzy at the prospect of public money being spent on a public good. Depending on the kind of railway line built, it could take between 4 and 8 years to construct – a good project on which our many unemployed construction workers (skiled and unskilled alike) could work, not to mention the jobs that would be created on a permanent basis thereafter, given that you need people to run these things. But no, it’s a terrible waste of money to put a piece of first world infrastructure in place. One of the many mainstream economists given airtime on RTÉ radio for their in-your-face views on how the economy should operate made what I’m sure he thought was a gotcha! point in relation to the possibility of the rail link and any possible benefits to the economy: namely, “sure, there’ll be jobs in construction, but what do you do when the thing is built??”. Whereas a job at some stinking call centre in the middle of nowhere is a solid career! As you can imagine, I’ve been giving my own personal stimulus to the radio sales industry in this country recently, by chucking mine out the window, and replacing it with another one.

The ‘public sector can’t create jobs’ meme is one that drives me particularly crazy, it’s nothing more than a theological belief – in fact, it’s just plain wrong whatever way you look at it. Even the phoney concern about a nation’s deficit is prima facie plausible, as long as you don’t consider it for more than a second. If anything, could you really say that jobs are ‘created’ as such in the private sector? Now, I have to come clean – I’ve never run a business in my life, but if I did, I would presume I wasn’t doing so to ‘create jobs’ and ‘drive the economy’ as the neoliberal phoney dogma would have it. The only reason, surely, that I would advertise a vacancy is that I need someone to fill said vacancy in order to maximise my potential profit, else I won’t be able to run my business without great physical/logistical/personal cost to myself, no? (Oh, but don’t worry, the Government have stepped in and sorted that one out too – they’ve set up an ‘internship’ scheme called ‘JobBridge’, whereby highly qualified unemployed people who have been on the dole for more than six months can get ‘valuable experience’ for an extra fifty euros on top of their normal dole entitlements, and work with companies who really, really need highly qualified people that they don’t want to pay. Needless to say, there have been plenty of hairdressers, restaurants, etc., offering ‘internships’. And just in case the poor employers can’t cope with having free labour, they’re getting their PRSI/USC (social security) contributions slashed – now that’s real enterprise!)

Anyway, thanks, Bill, addressing this particular topic in this post.

One thing I’ve been thinking about, and only because of the political realities in the US (and elsewhere), is whether it is possible, if not necessarily optimal, to increase aggregate demand with a balanced budget (or smaller government deficit than the private sector’s net savings desire plus external deficit) via the “balanced-budget multiplier.”

Whether or not it makes perfect sense to do so in theory, if it eases the suffering of the unemployed by getting them back to work and is more politically doable, why not do that?

Taking the Y=(G-T)+(I-S)+(X-M) sectoral equation, if an increase in T came almost exclusively from S (as opposed to I), the net effect on aggregate demand would be very small, if negative. And if any increase in G went mostly into I, the net effect on aggregate demand would be great, while positive.

This seems to be what Stiglitz is getting at. And it may be that is isn’t a perfect way to increase demand and get people back to work, but it might still be good. Given the political climate we’re in, would it be wise to let the perfect be the enemy of the good?

(And I understand the need to get people out of their outmoded thinking by showing them how the modern monetary system really works and to advocate for the best policy in the long run, but I’m just proposing a shorter-term strategy for getting something done, given the political constraints that cannot be eliminated tomorrow.)

MSNBC Republican Debate In 45 Seconds

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sTZrMNPhQAc

It doesn’t invalidate your main point, but this OECD data on state employment doesn’t pass the common sense validity test. Much of the variation must be explained by failure in normalisation (differences in status can make some employees with a full state employee status counted in in one country and out in another where the state pays people to do the same job but without full public employee status). The scale of the differences between some pretty similar countries is just not credible. Does the OECD provide an estimate of how much they expect their data to correlate with reality?

“If you define the role of government to advance public purpose…”

Therein lies the crux of the matter. Government has long since ceased to have this role, and it seems we are a little hesitant to really confront this. While the masses have been distracted with consumerist visions, politically euthanised, and taught to reject government power while corporate power silently and creepingly takes its place, the nature of government has changed; democracy has become corporatocracy, run by sociopathic elites with no concern for anything beyond their own personal aggrandisement.

Until we recognise the fact that our leaders no longer act in the public interest, and stop pretending that tinkering around the edges of an inherently corrupt system can generate any meaningful reform, we are destined to live lives of increasing impoverishment and servitude.

@Caran – Oh for goodness sake. What I’m constantly floored by is how this has gone global, including the policy prescriptions. It’s as if I could be plopped into the middle of Ireland and watch your TV politicians and were it not for the accents, feel right at home. If your government wasn’t also deciding to protect it’s military contractors at all costs, the same people would be in charge of it.

@ Blixa

Go to the data source to get a better understanding of this graph.

…and…

…and…

One writer above criticised neolcassical-neoliberal economics by saying, “The triumph of mediocrity is the phrase that springs to mind when you see what’s happening.”

I think the Salieri character’s arch statement from the movie “Amadeus” comes to mind.

“No, no, no! They have yet to achieve mediocrity.”