Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – September 10, 2011 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

* Tuesday, September 11, 1973 – right-wing forces aided by the US overthrew the elected government Chile. It was a terrorist act we should continue to remember like other terrorist acts!

Question 1:

When a sovereign government issues debt the overall holdings of financial assets held by the non-government sector $-for-$ does not change.

The answer is True .

The fundamental principles that arise in a fiat monetary system are as follows.

- The central bank sets the short-term interest rate based on its policy aspirations.

- Government spending is independent of borrowing and the latter best thought of as coming after spending.

- Government spending provides the net financial assets (bank reserves) which ultimately represent the funds used by the non-government agents to purchase the debt.

- Budget deficits that are not accompanied by corresponding monetary operations (debt-issuance) put downward pressure on interest rates contrary to the myths that appear in macroeconomic textbooks about ‘crowding out’.

- The “penalty for not borrowing” is that the interest rate will fall to the bottom of the “corridor” prevailing in the country which may be zero if the central bank does not offer a return on reserves.

- Government debt-issuance is a “monetary policy” operation rather than being intrinsic to fiscal policy, although in a modern monetary paradigm the distinctions between monetary and fiscal policy as traditionally defined are moot.

National governments have cash operating accounts with their central bank. The specific arrangements vary by country but the principle remains the same. When the government spends it debits these accounts and credits various bank accounts within the commercial banking system. Deposits thus show up in a number of commercial banks as a reflection of the spending. It may issue a cheque and post it to someone in the private sector whereupon that person will deposit the cheque at their bank. It is the same effect as if it had have all been done electronically.

All federal spending happens like this. You will note that:

- Governments do not spend by “printing money”. They spend by creating deposits in the private banking system. Clearly, some currency is in circulation which is “printed” but that is a separate process from the daily spending and taxing flows.

- There has been no mention of where they get the credits and debits come from! The short answer is that the spending comes from no-where but we will have to wait for another blog soon to fully understand that. Suffice to say that the Federal government, as the monopoly issuer of its own currency is not revenue-constrained. This means it does not have to “finance” its spending unlike a household, which uses the fiat currency.

- Any coincident issuing of government debt (bonds) has nothing to do with “financing” the government spending.

All the commercial banks maintain reserve accounts with the central bank within their system. These accounts permit reserves to be managed and allows the clearing system to operate smoothly. The rules that operate on these accounts in different countries vary (that is, some nations have minimum reserves others do not etc). For financial stability, these reserve accounts always have to have positive balances at the end of each day, although during the day a particular bank might be in surplus or deficit, depending on the pattern of the cash inflows and outflows. There is no reason to assume that these flows will exactly offset themselves for any particular bank at any particular time.

The central bank conducts “operations” to manage the liquidity in the banking system such that short-term interest rates match the official target – which defines the current monetary policy stance. The central bank may: (a) Intervene into the interbank (overnight) money market to manage the daily supply of and demand for reserve funds; (b) buy certain financial assets at discounted rates from commercial banks; and (c) impose penal lending rates on banks who require urgent funds, In practice, most of the liquidity management is achieved through (a). That being said, central bank operations function to offset operating factors in the system by altering the composition of reserves, cash, and securities, and do not alter net financial assets of the non-government sectors.

Fiscal policy impacts on bank reserves – government spending (G) adds to reserves and taxes (T) drains them. So on any particular day, if G > T (a budget deficit) then reserves are rising overall. Any particular bank might be short of reserves but overall the sum of the bank reserves are in excess. It is in the commercial banks interests to try to eliminate any unneeded reserves each night given they usually earn a non-competitive return. Surplus banks will try to loan their excess reserves on the Interbank market. Some deficit banks will clearly be interested in these loans to shore up their position and avoid going to the discount window that the central bank offeres and which is more expensive.

The upshot, however, is that the competition between the surplus banks to shed their excess reserves drives the short-term interest rate down. These transactions net to zero (a equal liability and asset are created each time) and so non-government banking system cannot by itself (conducting horizontal transactions between commercial banks – that is, borrowing and lending on the interbank market) eliminate a system-wide excess of reserves that the budget deficit created.

What is needed is a vertical transaction – that is, an interaction between the government and non-government sector. So bond sales can drain reserves by offering the banks an attractive interest-bearing security (government debt) which it can purchase to eliminate its excess reserves.

However, the vertical transaction just offers portfolio choice for the non-government sector rather than changing the holding of financial assets.

Option (a) “increases the assets that are held by the non-government sector $-for-$” is thus incorrect.

Option (c) “reduces the capacity of the private sector to borrow from banks because they use their deposits to buy the bonds” is clearly not correct.

This is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need deposits and reserves before they can lend. Mainstream macroeconomics wrongly asserts that banks only lend if they have prior reserves. The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But this is a completely incorrect depiction of how banks operate. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Quantitative easing 101

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Will we really pay higher interest rates?

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

Question 2:

Ignoring any reserve requirements that might be imposed, if the central bank pays a positive interest rate on overnight reserves held by the commercial banks then it may still have to conduct open market operations as a means of ensuring that levels of bank reserves are consistent with its policy target rate of interest.

The answer is True.

The first thing to understand is the way in which monetary policy is implemented in a modern monetary economy. You will see that this is contrary to the account of monetary policy in mainstream macroeconomics textbooks, which tries to tell students that monetary policy describes the processes by which the central bank determines “the total amount of money in existence or to alter that amount”.

In Mankiw’s Principles of Economics (Chapter 27 First Edition) he say that the central bank has “two related jobs”. The first is to “regulate the banks and ensure the health of the financial system” and the second “and more important job”:

… is to control the quantity of money that is made available to the economy, called the money supply. Decisions by policymakers concerning the money supply constitute monetary policy (emphasis in original).

How does the mainstream see the central bank accomplishing this task? Mankiw says:

Fed’s primary tool is open-market operations – the purchase and sale of U.S government bonds … If the FOMC decides to increase the money supply, the Fed creates dollars and uses them buy government bonds from the public in the nation’s bond markets. After the purchase, these dollars are in the hands of the public. Thus an open market purchase of bonds by the Fed increases the money supply. Conversely, if the FOMC decides to decrease the money supply, the Fed sells government bonds from its portfolio to the public in the nation’s bond markets. After the sale, the dollars it receives for the bonds are out of the hands of the public. Thus an open market sale of bonds by the Fed decreases the money supply.

This description of the way the central bank interacts with the banking system and the wider economy is totally false. The reality is that monetary policy is focused on determining the value of a short-term interest rate. Central banks cannot control the money supply. To some extent these ideas were a residual of the commodity money systems where the central bank could clearly control the stock of gold, for example. But in a credit money system, this ability to control the stock of “money” is undermined by the demand for credit.

The theory of endogenous money is central to the horizontal analysis in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). When we talk about endogenous money we are referring to the outcomes that are arrived at after market participants respond to their own market prospects and central bank policy settings and make decisions about the liquid assets they will hold (deposits) and new liquid assets they will seek (loans).

The essential idea is that the “money supply” in an “entrepreneurial economy” is demand-determined – as the demand for credit expands so does the money supply. As credit is repaid the money supply shrinks. These flows are going on all the time and the stock measure we choose to call the money supply, say M3 (Currency plus bank current deposits of the private non-bank sector plus all other bank deposits from the private non-bank sector) is just an arbitrary reflection of the credit circuit.

So the supply of money is determined endogenously by the level of GDP, which means it is a dynamic (rather than a static) concept.

Central banks clearly do not determine the volume of deposits held each day. These arise from decisions by commercial banks to make loans. The central bank can determine the price of “money” by setting the interest rate on bank reserves. Further expanding the monetary base (bank reserves) as we have argued in recent blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – does not lead to an expansion of credit.

With this background in mind, the question is specifically about the dynamics of bank reserves which are used to satisfy any imposed reserve requirements and facilitate the payments system. These dynamics have a direct bearing on monetary policy settings. Given that the dynamics of the reserves can undermine the desired monetary policy stance (as summarised by the policy interest rate setting), the central banks have to engage in liquidity management operations.

What are these liquidity management operations?

Well you first need to appreciate what reserve balances are.

The New York Federal Reserve Bank’s paper – Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy said that:

… reserve balances are used to make interbank payments; thus, they serve as the final form of settlement for a vast array of transactions. The quantity of reserves needed for payment purposes typically far exceeds the quantity consistent with the central bank’s desired interest rate. As a result, central banks must perform a balancing act, drastically increasing the supply of reserves during the day for payment purposes through the provision of daylight reserves (also called daylight credit) and then shrinking the supply back at the end of the day to be consistent with the desired market interest rate.

So the central bank must ensure that all private cheques (that are funded) clear and other interbank transactions occur smoothly as part of its role of maintaining financial stability. But, equally, it must also maintain the bank reserves in aggregate at a level that is consistent with its target policy setting given the relationship between the two.

So operating factors link the level of reserves to the monetary policy setting under certain circumstances. These circumstances require that the return on “excess” reserves held by the banks is below the monetary policy target rate. In addition to setting a lending rate (discount rate), the central bank also sets a support rate which is paid on commercial bank reserves held by the central bank.

Many countries (such as Australia and Canada) maintain a default return on surplus reserve accounts (for example, the Reserve Bank of Australia pays a default return equal to 25 basis points less than the overnight rate on surplus Exchange Settlement accounts). Other countries like the US and Japan have historically offered a zero return on reserves which means persistent excess liquidity would drive the short-term interest rate to zero.

The support rate effectively becomes the interest-rate floor for the economy. If the short-run or operational target interest rate, which represents the current monetary policy stance, is set by the central bank between the discount and support rate. This effectively creates a corridor or a spread within which the short-term interest rates can fluctuate with liquidity variability. It is this spread that the central bank manages in its daily operations.

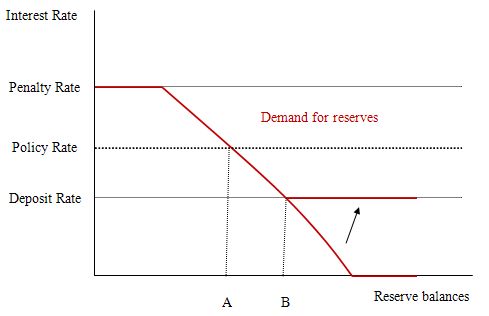

So the issue then becomes – at what level should the support rate be set? To answer that question, I reproduce a version of teh diagram from the FRBNY paper which outlined a simple model of the way in which reserves are manipulated by the central bank as part of its liquidity management operations designed to implement a specific monetary policy target (policy interest rate setting).

I describe the FRBNY model in detail in the blog – Understanding central bank operations so I won’t repeat that explanation.

The penalty rate is the rate the central bank charges for loans to banks to cover shortages of reserves. If the interbank rate is at the penalty rate then the banks will be indifferent as to where they access reserves from so the demand curve is horizontal (shown in red).

Once the price of reserves falls below the penalty rate, banks will then demand reserves according to their requirments (the legal and the perceived). The higher the market rate of interest, the higher is the opportunity cost of holding reserves and hence the lower will be the demand. As rates fall, the opportunity costs fall and the demand for reserves increases. But in all cases, banks will only seek to hold (in aggregate) the levels consistent with their requirements.

At low interest rates (say zero) banks will hold the legally-required reserves plus a buffer that ensures there is no risk of falling short during the operation of the payments system.

Commercial banks choose to hold reserves to ensure they can meet all their obligations with respect to the clearing house (payments) system. Because there is considerable uncertainty (for example, late-day payment flows after the interbank market has closed), a bank may find itself short of reserves. Depending on the circumstances, it may choose to keep a buffer stock of reserves just to meet these contingencies.

So central bank reserves are intrinsic to the payments system where a mass of interbank claims are resolved by manipulating the reserve balances that the banks hold at the central bank. This process has some expectational regularity on a day-to-day basis but stochastic (uncertain) demands for payments also occur which means that banks will hold surplus reserves to avoid paying any penalty arising from having reserve deficiencies at the end of the day (or accounting period).

To understand what is going on not that the diagram is representing the system-wide demand for bank reserves where the horizontal axis measures the total quantity of reserve balances held by banks while the vertical axis measures the market interest rate for overnight loans of these balances

In this diagram there are no required reserves (to simplify matters). We also initially, abstract from the deposit rate for the time being to understand what role it plays if we introduce it.

Without the deposit rate, the central bank has to ensure that it supplies enough reserves to meet demand while still maintaining its policy rate (the monetary policy setting.

So the model can demonstrate that the market rate of interest will be determined by the central bank supply of reserves. So the level of reserves supplied by the central bank supply brings the market rate of interest into line with the policy target rate.

At the supply level shown as Point A, the central bank can hit its monetary policy target rate of interest given the banks’ demand for aggregate reserves. So the central bank announces its target rate then undertakes monetary operations (liquidity management operations) to set the supply of reserves to this target level.

So contrary to what Mankiw’s textbook tells students the reality is that monetary policy is about changing the supply of reserves in such a way that the market rate is equal to the policy rate.

The central bank uses open market operations to manipulate the reserve level and so must be buying and selling government debt to add or drain reserves from the banking system in line with its policy target.

If there are excess reserves in the system and the central bank didn’t intervene then the market rate would drop towards zero and the central bank would lose control over its target rate (that is, monetary policy would be compromised).

As explained in the blog – Understanding central bank operations – the introduction of a support rate payment (deposit rate) whereby the central bank pays the member banks a return on reserves held overnight changes things considerably.

It clearly can – under certain circumstances – eliminate the need for any open-market operations to manage the volume of bank reserves.

In terms of the diagram, the major impact of the deposit rate is to lift the rate at which the demand curve becomes horizontal (as depicted by the new horizontal red segment moving up via the arrow).

This policy change allows the banks to earn overnight interest on their excess reserve holdings and becomes the minimum market interest rate and defines the lower bound of the corridor within which the market rate can fluctuate without central bank intervention.

So in this diagram, the market interest rate is still set by the supply of reserves (given the demand for reserves) and so the central bank still has to manage reserves appropriately to ensure it can hit its policy target.

If there are excess reserves in the system in this case, and the central bank didn’t intervene, then the market rate will drop to the support rate (at Point B).

So if the central bank wants to maintain control over its target rate it can either set a support rate below the desired policy rate (as in Australia) and then use open market operations to ensure the reserve supply is consistent with Point A or set the support (deposit) rate equal to the target policy rate.

The answer to the question is thus True because it all depends on where the support rate is set. Only if it set equal to the policy rate will there be no need for the central bank to manage liquidity via open market operations.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Understanding central bank operations

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 3:

If participation rates are constant, percentage unemployment will not change as long as employment growth matches the pace of growth in the working age population (people above 15 years of age).

The answer is True.

The Civilian Population is shorthand for the working age population and can be defined as all people between 15 and 65 years of age or persons above 15 years of age, depending on rules governing retirement. The working age population is then decomposed within the Labour Force Framework (used to collect and disseminate labour force data) into two categories: (a) the Labour Force; and (b) Not in the Labour Force. This demarcation is based on activity principles (willingness, availability and seeking work or being in work).

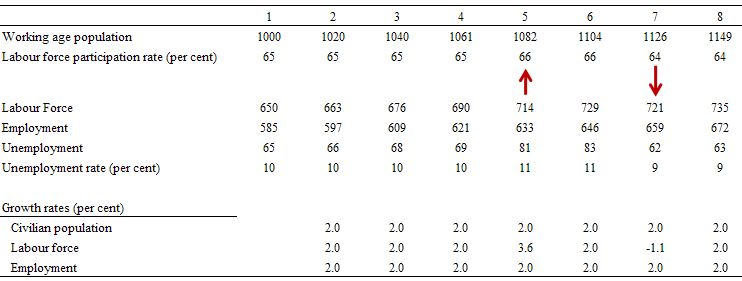

The participation rate is defined as the proportion of the working age population that is in the labour force. So if the working age population was 1000 and the participation rate was 65 per cent, then the labour force would be 650 persons. So the labour force can vary for two reasons: (a) growth in the working age population – demographic trends; and (b) changes in the participation rate.

The labour force is decomposed into employment and unemployment. To be employed you typically only have to work one hour in the survey week. To be unemployed you have to affirm that you are available, willing and seeking employment if you are not working one hour or more in the survey week. Otherwise, you will be classified as not being in the labour force.

So the hidden unemployed are those who give up looking for work (they become discouraged) yet are willing and available to work. They are classified by the statistician as being not in the labour force. But if they were offered a job today they would immediately accept it and so are in no functional way different from the unemployed.

When economic growth wanes, participation rates typically fall as the hidden unemployed exit the labour force. This cyclical phenomenon acts to reduce the official unemployment rate.

So clearly, the working age population is a much larger aggregate than the labour force and, in turn, employment. Clearly if the participation rate is constant then the labour force will grow at the same rate as the civilian population. And if employment grows at that rate too then while the gap between the labour force and employment will increase in absolute terms (which means that unemployment will be rising), that gap in percentage terms will be constant (that is the unemployment rate will be constant).

The following Table simulates a simple labour market for 8 periods. You can see for the first 4 periods, that unemployment rises steadily over time but the unemployment rate is constant. During this time span employment growth is equal to the growth in the underlying working age population and the participation rate doesn’t change. So the unemployment rate will be constant although more people will be unemployed.

In Period 5, the participation rate rises so that even though there is constant growth (2 per cent) in the working age population, the labour force growth rate rises to 3.6 per cent. Now unemployment jumps disproportionately because employment growth (2 per cent) is not keeping pace with the growth in new entrants to the labour force and as a consequence the unemployent rate rises to 11 per cent.

In Period 6, employment growth equals labour force growth (because the participation rate settles at the new level – 66 per cent) and the unemployment rate is constant.

In Period 7, the participation rate plunges to 64 per cent and the labour force contracts (as the higher proportion of the working age population are inactive – that is, not participating). As a consequence, unemployment falls dramatically as does the unemployment rate. But this is hardly a cause for celebration – the unemployed are now hidden by the statistician “outside the labour force”.

Understanding these aggregates is very important because as we often see when Labour Force data is released by national statisticians the public debate becomes distorted by the incorrect way in which employment growth is represented in the media.

In situations where employment growth keeps pace with the underlying population but the participation rate falls then the unemployment rate will also fall. By focusing on the link between the positive employment growth and the declining unemployment there is a tendency for the uninformed reader to conclude that the economy is in good shape. The reality, of-course, is very different.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 4:

National government taxation creates unemployment, other things equal.

The answer is True.

First, to clear the ground we state clearly that a sovereign government is the monopoly issuer of the currency and is never revenue-constrained. So it never has to “obey” the constraints that the private sector always has to obey.

The foundation of many mainstream macroeconomic arguments is the fallacious analogy they draw between the budget of a household/corporation and the government budget. However, there is no parallel between the household (for example) which is clearly revenue-constrained because it uses the currency in issue and the national government, which is the issuer of that same currency.

The choice (and constraint) sets facing a household and a sovereign government are not alike in any way, except that both can only buy what is available for sale. After that point, there is no similarity or analogy that can be exploited.

Of-course, the evolution in the 1960s of the literature on the so-called government budget constraint (GBC), was part of a deliberate strategy to argue that the microeconomic constraint facing the individual applied to a national government as well. Accordingly, they claimed that while the individual had to “finance” its spending and choose between competing spending opportunities, the same constraints applied to the national government. This provided the conservatives who hated public activity and were advocating small government, with the ammunition it needed.

So the government can always spend if there are goods and services available for purchase, which may include idle labour resources. This is not the same thing as saying the government can always spend without concern for other dimensions in the aggregate economy.

For example, if the economy was at full capacity and the government tried to undertake a major nation building exercise then it might hit inflationary problems – it would have to compete at market prices for resources and bid them away from their existing uses.

In those circumstances, the government may – if it thought it was politically reasonable to build the infrastructure – quell demand for those resources elsewhere – that is, create some unemployment. How? By increasing taxes.

So to answer the question correctly, you need to understand the role that taxes play in a fiat currency system.

In a fiat monetary system the currency has no intrinsic worth. Further the government has no intrinsic financial constraint. Once we realise that government spending is not revenue-constrained then we have to analyse the functions of taxation in a different light. The starting point of this new understanding is that taxation functions to promote offers from private individuals to government of goods and services in return for the necessary funds to extinguish the tax liabilities.

In this way, it is clear that the imposition of taxes creates unemployment (people seeking paid work) in the non-government sector and allows a transfer of real goods and services from the non-government to the government sector, which in turn, facilitates the government’s economic and social program.

The crucial point is that the funds necessary to pay the tax liabilities are provided to the non-government sector by government spending. Accordingly, government spending provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

So it is now possible to see why mass unemployment arises. It is the introduction of State Money (government taxing and spending) into a non-monetary economics that raises the spectre of involuntary unemployment. As a matter of accounting, for aggregate output to be sold, total spending must equal total income (whether actual income generated in production is fully spent or not each period). Involuntary unemployment is idle labour offered for sale with no buyers at current prices (wages).

Unemployment occurs when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account, but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns, other things equal. As a result, involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services translates into decreased output and employment. In this situation, nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless those cuts somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save, and thereby increase spending.

The purpose of State Money is for the government to move real resources from private to public domain. It does so by first levying a tax, which creates a notional demand for its currency of issue. To obtain funds needed to pay taxes and net save, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed units of the currency. This includes, of-course, the offer of labour by the unemployed. The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

This analysis also sets the limits on government spending. It is clear that government spending has to be sufficient to allow taxes to be paid. In addition, net government spending is required to meet the private desire to save (accumulate net financial assets). From the previous paragraph it is also clear that if the Government doesn’t spend enough to cover taxes and desire to save the manifestation of this deficiency will be unemployment.

Keynesians have used the term demand-deficient unemployment. In our conception, the basis of this deficiency is at all times inadequate net government spending, given the private spending decisions in force at any particular time.

So the answer should now be obvious. If the economy is to remain at full employment the government has to command private resources. Taxation is the vehicle that a sovereign government uses to “free up resources” so that it can use them itself. But taxation has nothing to do with “funding” of the government spending.

To understand how taxes are used to attenuate demand please read this blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- The budget deficits will increase taxation!

- Will we really pay higher taxes?

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Functional finance and modern monetary theory

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

Premium Question 5:

Mainstream monetary theory highlights the concept of a money multiplier which says that the money supply is some multiple of the monetary base (bank reserves and currency). There is a direct relationship between the monetary base and the the money supply in a modern monetary economy.

The answer is True.

Mainstream macroeconomics textbooks are completely wrong when they discuss the credit-creation capacity of commercial banks and use the concept of the money multiplier to describe the relationship between the monetary base and the money supply.

They posit that the multiplier m transmits changes in the so-called monetary base (MB) (the sum of bank reserves and currency at issue) into changes in the money supply (M). The chapters on money usually present some arcane algebra which is deliberately designed to impart a sense of gravitas or authority to the students who then mindlessly ape what is in the textbook.

They rehearse several times in their undergraduate courses (introductory and intermediate macroeconomics; money and banking; monetary economics etc) the mantra that the money multiplier is usually expressed as the inverse of the required reserve ratio plus some other novelties relating to preferences for cash versus deposits by the public.

Accordingly, the students learn that if the central bank told private banks that they had to keep 10 per cent of total deposits as reserves then the required reserve ratio (RRR) would be 0.10 and m would equal 1/0.10 = 10. More complicated formulae are derived when you consider that people also will want to hold some of their deposits as cash. But these complications do not add anything to the story.

The formula for the determination of the money supply is: M = m x MB. So if a $1 is newly deposited in a bank, the money supply will rise (be multiplied) by $10 (if the RRR = 0.10). The way this multiplier is alleged to work is explained as follows (assuming the bank is required to hold 10 per cent of all deposits as reserves):

- A person deposits say $100 in a bank.

- To make money, the bank then loans the remaining $90 to a customer.

- They spend the money and the recipient of the funds deposits it with their bank.

- That bank then lends 0.9 times $90 = $81 (keeping 0.10 in reserve as required).

- And so on until the loans become so small that they dissolve to zero

None of this is remotely accurate in terms of depicting how the banks make loans. It is an important device for the mainstream because it implies that banks take deposits to get funds which they can then on-lend. But prudential regulations require they keep a little in reserve. So we get this credit creation process ballooning out due to the fractional reserve requirements.

The money multiplier myth also leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted home to the “government”. This leads to claims that if the government runs a budget deficit then it has to issue bonds to avoid causing hyperinflation. Nothing could be further from the truth.

That is nothing like the way the banking system operates in the real world. The idea that the monetary base (the sum of bank reserves and currency) leads to a change in the money supply via some multiple is not a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates.

First, the central bank does not have the capacity to control the money supply in a modern monetary system. In the world we live in, bank loans create deposits and are made without reference to the reserve positions of the banks. The bank then ensures its reserve positions are legally compliant as a separate process knowing that it can always get the reserves from the central bank. The only way that the central bank can influence credit creation in this setting is via the price of the reserves it provides on demand to the commercial banks.

Second, this suggests that the decisions by banks to lend may be influenced by the price of reserves rather than whether they have sufficient reserves. They can always get the reserves that are required at any point in time at a price, which may be prohibitive.

Third, the money multiplier story has the central bank manipulating the money supply via open market operations. So they would argue that the central bank might buy bonds to the public to increase the money base and then allow the fractional reserve system to expand the money supply. But a moment’s thought will lead you to conclude this would be futile unless a support rate on excess reserves equal to the current policy rate was being paid.

Why? The open market purchase would increase bank reserves and the commercial banks, in lieu of any market return on the overnight funds, would try to place them in the interbank market. Of-course, any transactions at this level (they are horizontal) net to zero so all that happens is that the excess reserve position of the system is shuffled between banks. But in the process the interbank return would start to fall and if the process was left to resolve, the overnight rate would fall to zero and the central bank would lose control of its monetary policy position (unless it was targetting a zero interest rate).

In lieu of a support rate equal to the target rate, the central bank would have to sell bonds to drain the excess reserves. The same futility would occur if the central bank attempted to reduce the money supply by instigating an open market sale of bonds.

In all cases, the central bank cannot influence the money supply in this way.

Fourth, given that the central bank adds reserves on demand to maintain financial stability and this process is driven by changes in the money supply as banks make loans which create deposits.

So the operational reality is that the dynamics of the monetary base (MB) are driven by the changes in the money supply which is exactly the reverse of the causality presented by the monetary multiplier.

So in fact we might write MB = M/m.

Thus, while the concept of money multiplier is an incorrect depiction of the way the monetary system works, it remains that there is a direct relationship between the monetary base and the “money supply”.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

- Teaching macroeconomics students the facts

- Lost in a macroeconomics textbook again

- Lending is capital- not reserve-constrained

- Oh no … Bernanke is loose and those greenbacks are everywhere

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- 100-percent reserve banking and state banks

- Money multiplier and other myths

What’s the difference between Q1 today:

Question 1:

When a sovereign government issues debt the overall holdings of financial assets held by the non-government sector $-for-$ does not change.

The answer is True .

and Q2 here:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=15747

Q2 – Question 2:

When the government matches it deficit with new debt issues the non-government sector wealth rises.

The answer is True.

The answer is in the answer to the previous question 2.

“The question lures you into thinking it is the bond-issuance that drives the rise in non-government wealth when, in fact, it is the budget deficit that adds to non-government wealth irrespective of whether bonds are issued or not.”

Bill you said,

“Government debt-issuance is a “monetary policy” operation rather than being intrinsic to fiscal policy, although in a modern monetary paradigm the distinctions between monetary and fiscal policy as traditionally defined are moot. ”

Would it not be reasonable to consider fiscal policy a sub-set of monetary policy, given that it adds / subtracts…..well, “money” to/from the non-government sector? This is certainly how I understand it best.

Kind Regards

Further to my comment above, we could perhaps also say “the most fundamental form of monetary policy is fiscal policy”.

@ FedUp

Neil Wilson is right – this week’s question does not specify that the debt issued is deficit-financed. But further, it is never the case that, merely by swapping bonds for cash, the Fed can increase privately held financial assets. As Warren Mosler likes to point out, however, doing so can decrease private income – because the flow of risk-free interest on T-bonds goes to the Treasury via the Fed instead of to the private sector.

I have 2 simple questions.

First of all, regarding Question 2:

Ok, money supply. MMT says that CB cannot and does not influence money supply. It can only influence ammount of reserves, hence price of credit. But let’s say CB buys all(or some) the U.S. bonds in the market. Wouldn’t it result in increase in either currency holdings or deposits at the commercial banks? If I have a bond(a saving account at the Fed) and Fed buys that bond from me crediting my bank account, doesn’t it mean that money supply just increased by the amount Fed credited my account? Therefore, I have a right to change that deposit to currency. So wouldn’t it actually increase money supply?

Question 4:

Reading that question I made an assumption that economy could be at full employment and government could have spent more money than it was required, hence inflation arrised(from excess government spending). If that’s the case, wouldn’t increased taxation just reduce inflation and not employment?

” It can only influence ammount of reserves, hence price of credit. ”

It sets the price of reserves which influences the price of credit. The amount of reserves is always what is required to clear the system at that price (otherwise the CB quickly loses the ability to set the price).

“doesn’t it mean that money supply just increased by the amount Fed credited my account?”

The bond ceased to exist in the private sector and some reserves come into existence instead in the private sector. The amount of ‘money’ hasn’t changed.

“Therefore, I have a right to change that deposit to currency”

You do with a bond. Sell it and ask for cash. When you change a deposit to currency you ‘sell’ it as well. What that does is remove an amount of bonds/reserves from the private sector system and an amount of currency turns up at the bank in an armoured truck.

The trick is to get the phrase ‘money supply’ out of your head. It isn’t supplied. It is created and destroyed dynamically based upon economic demand at the current price.

Neil, thank you for your response. I do agree with every point you make. Even though I still don’t find an exact answer to my question.

I CAN sell a bond and get deposit/cash, but isn’t that a fallacy of composition? I mean it works for me, but it doesn’t work on aggregate. Someone still needs to hold that bond. It’s like MMT says – all “horizontal” transactions net to zero.

Money supply, by definition is “the entire quantity of bills, coins, loans, credit and other liquid instruments in a country’s economy.”

So if a CB bought a bond that would result in increase in either new deposit or equivalent amount of curreny. MMT somehow concentrates on reserves only. But, say, government credited my bank account by 10 trilion dollars. I guess it first need to credit my bank’s reserve account at the Fed, but still, eventually I see 10 trillion dollars in my bank account. So can’t I actually spend all that money for real goods and services and increase output or inflation(if economy is at full employment)? Wouldn’t it mean that money supply has actually risen by 10 trillion?

I mean, if a CB swaps my bond for currency or deposits, doesn’t it mean that now there is more money in the economy? I mean from pure technical point of view.

Q2 from the past quiz – Question 2:

When the government matches it deficit with new debt issues the non-government sector wealth rises.

The answer is True.

I believe I understand that one.

It is Q1 here I don’t entirely get.

Question 1:

When a sovereign government issues debt the overall holdings of financial assets held by the non-government sector $-for-$ does NOT change.

The answer is True .

Is it because it says debt with no mention of whether there is a gov’t deficit, or does it have something to do with overall holdings of financial assets held by the non-government sector?

Thanks!

FedUp,

“Is it because it says debt with no mention of whether there is a gov’t deficit, or does it have something to do with overall holdings of financial assets held by the non-government sector?”

It is because a govt debt issuance swaps one financial asset (reserves) with another (bonds), so no change in net financial assets in the non-govt sector. It is best to completely seperate debt issuance from budget deficits and treat them seperately in your mind. Only deficits add net financial assets (as “money”/reserves), govt debt issuance simply changes one type of NFA into another with no overall change.

Edgaras,

“I CAN sell a bond and get deposit/cash, but isn’t that a fallacy of composition? I mean it works for me, but it doesn’t work on aggregate. Someone still needs to hold that bond.”

I struggled with this for a while, and i’m still not sure i’ve got it right but:

The mainstream might say that because not everyone can liquidate their bonds that there is a shortage of money to spend on investment opportunities, as the main reason why someone would want to liquidate a bond is because they see such an investment opportunity.

This sounds compelling until you realise the logic is upside down – investment isn’t limited by money available to invest, it is limited by the opportunities to invest. In a demand deficient economy there may only be $10 Billion of investment opportunity, and so if you are the one to liquidate the bond first then you get to make that investment.

Therefore Net Financial Assets don’t need to be liquid in aggregate, only in sufficient quantity to meet the opportunity to invest.

That’s how I see it. Please someone correct me if i’m wrong.

Edgaras said: “Money supply, by definition is “the entire quantity of bills, coins, loans, credit and other liquid instruments in a country’s economy.””

Well, I guess you haven’t run into people like scott sumner and others who say “money supply” is monateary base (currency plus central bank reserves). Others say M1. Others say M2 and on and on and on. Too many definitions of money. That is why I recommend not using the term “money”.

Make that monetary base.

Fed Up,

I think of money as anything liquid enough to immediately purchase goods and services, or to invest with no conversion transactions necessary. i’m not sure how that translates into Mx.

Fed Up,

I think you have used the phrase “medium of exchange”. I think that describes money perfectly. Money to me is NOT reserves, it is currency or deposits.

CharlesJ said: “Fed Up,

I think you have used the phrase “medium of exchange”. I think that describes money perfectly. Money to me is NOT reserves, it is currency or deposits.”

I agree. I’m glad someone is listening. Any idea of how I can get that thru to the economists of the world?

I’ll add this. Medium of exchange is used out in the real economy. Although there are some differences, the demand deposits from BOTH private and gov’t debt both act as medium of exchange. To me, central bank reserves are a type of “medium of exchange” used only in the banking system covered by the member banks of the central bank. How does that sound?

Edgaras says: “But let’s say CB buys all(or some) the U.S. bonds in the market. Wouldn’t it result in increase in either currency holdings or deposits at the commercial banks? If I have a bond(a saving account at the Fed) and Fed buys that bond from me crediting my bank account, doesn’t it mean that money supply just increased by the amount Fed credited my account? Therefore, I have a right to change that deposit to currency. So wouldn’t it actually increase money supply?”

Edgaras, first I am going to change money supply to medium of exchange supply. Next, let’s assume the fed does not buy from the public, but it only buys from member banks. I think that is true, but someone can correct me if I’m wrong. The fed creates a central bank reserve from “nothing” (QE program). It then swaps a 10 year treasury with the central bank reserve from a member bank. The fed overpays because it wants the 10 year interest rate to come down, and the market goes along (price inflation is low by their definition). The member bank creates a demand deposit from “nothing”. Now you sell (actually swap) your 10 year treasury bought in 2006 to the member bank for a gain. The member bank gets the 10 year treasury, and you get a demand deposit account markup in your account. The question is what do you do with your demand deposit(s), keep saving or spend now instead of in 2016. The other thing is with lower 10 year interest rates, the fed is hoping to sucker someone to go into debt to spend now. I hope there isn’t too much disagreement about that.

Here is where I might get some more disagreement. The way the system is set up now I consider the medium of exchange supply to be the debt supply. That means its velocity has to be between 0 and 1 and is either $52 trillion or $58 trillion in the USA depending on how things like Social Security are counted. Lower interest rates are about *TRYING* to get savers (usually excess savers) to spend now and more likely *TRYING* to get anyone else to go into debt to spend now. Getting savers to spend now is an increase in velocity and more debt is about increasing the amount of medium of exchange. So in MV = PY and with M being medium of exchange, both of those are about *TRYING* to affect PY.

Lastly, I said the central bank reserve and demand deposit were created from “nothing”. I’m trying to come up with a scenario where they were actually saved in the past and “hidden” from view, but they reappear when bonds are redeemed for medium of exchange.

So if Q1 said “When a sovereign government RUNS A DEFICIT AND issues debt …”, then the answer would be false? Correct?

CharlesJ said: “Fed Up,

I think you have used the phrase “medium of exchange”. I think that describes money perfectly. Money to me is NOT reserves, it is currency or deposits.”

To me, it is currency plus deposits.

Fed Up, thanks for your responses, as far as I know, there are totally right, but you still missed my point. I didn’t ask about bond preferances, about abilities and opportunities to invest. Of course, if Fed buys your bonds, you won’t start spending all that money for real goods and services, since you could have done that any time you wanted. The thing I struggle with is the whole “money supply” thing or “medium of exchange” thing as you prefer. I mean if Fed swaps a bond for newly created money, it results in increase in monetary base, that’s for sure. And therefore, I would like to say that it increases money supply as well. Maybe the impact is small and insignificant, but still it’s technically sound. Fed swaps bonds for deposits(reserves) and now people have more deposits/currency ON AGGREGATE. Probabbly they will buy another type of bonds or whatever, but my point is that it, technically, results in incease in money supply. Doesn’t it?

“I mean if Fed swaps a bond for newly created money, it results in increase in monetary base, that’s for sure. And therefore, I would like to say that it increases money supply as well.”

I don’t like the term “money” because there are too many definitions. I like to use currency, central bank reserves, and demand deposits (deposits) with medium of exchange being currency plus demand deposits. Next, I’m trying to imagine a scenario where QE isn’t actually new central bank reserves, but saved central bank reserves from the past. We’ll skip that for now.

The fed announces QE whatever number to buy 10 year gov’t bond.

They create a central bank reserve from “nothing”. That is an increase in the monetary base (currency plus central bank reserves).

They swap a 10 year treasury with a member bank.

First scenario: Nothing else happens (no one else wants to sell or go into debt). No medium of exchange is created (currency plus demand deposits).

Second scenario: You sell the 10 year treasury to the member bank, and a new demand deposit is created. The new demand deposit could have a velocity of zero. If you buy a CD from the same member bank, the new demand deposit could be “destroyed”. Just because a demand deposit is created (medium of exchange) doesn’t mean it will have a velocity or won’t be “destroyed”.

Fed Up,

“To me, central bank reserves are a type of “medium of exchange” used only in the banking system covered by the member banks of the central bank. How does that sound?”

That’s how I see it too. I don’t think MMT has to be too reticenct to talk about the difference between “broad money” and bonds – all my thinking says that it only confirms that MMT has got it right.

CharlesJ, I’d like to get MMT to admit that I believe it is possible to create more medium of exchange with private debt = 0, gov’t debt = 0, and the various levels of gov’t running a balanced budget. I believe the accounting looks like this:

savings of the rich plus savings of the lower and middle class = the balanced budget(s) of the various level(s) of gov’t plus the dissavings of the currency printing entity with currency and no bond/loan attached.

IMO, that would give the best chances of productivity gains and other things being distributed evenly between the major economic entities and distributed evenly in time.

You are saying :

“The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.”

I am just reading “Animal Spirits” by Shiller/Akerloff. On page 78 they say:

… when the FED , for example, does decide to buy bonds, the banks will have more reserves, and that will empower them to make more loans.

Doesn’t these statement contradict each other ?

What am I missing ?