The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Australian inflation rate – or rather – the banana rate

The Australian Bureau of Statistics released the Consumer Price Index, Australia data for the June 2011 quarter today and it revealed a significant easing of the inflation rate on last quarter (0.9 per cent compared to 1.6 per cent in March 2011). The annualised inflation rate rose to 3.6 per cent up from 3.3 per cent in the 12 months to March 2011. While many commentators are calling this the start of a spiral in core inflation spike the data is still being driven by ephemeral factors associated with the impacts of the natural disasters (floods and cyclones) that our food growing areas endured earlier this year. The major factors driving the inflation rate are food (and that is mostly bananas) and world oil price movements. I still consider these impacts to be mostly of a transitory nature. Given that the core inflation rate is still well within the RBA’s targeting band, I do not consider there is a case for an interest rate rise next week (using their own logic). Bananas cannot keep increasing by 470 per cent every 6 months. And if they do, they are easily substituted away from.

The summary results for the June 2011 quarter are as follows:

- The All Groups CPI rose by 0.9 per cent in the June quarter 2011 down from 1.6 per cent in the March quarter 2011.

- The All Groups CPI rose by 3.6 per cent over the 12 months to the June quarter 2011 up from an annualised rise of 3.3 per cent over the 12 months to March quarter 2011. This is because the June quarter 2010 rise was 0.6 per cent compared to 0.9 per cent in the June quarter 2011.

- The largest price rises were fruit (+26.9 per cent), automotive fuel (+4.0 per cent), hospital and medical services (+3.4per cent), furniture (+6.0 per cent), deposit and loan facilities (+2.1 per cent) and rents (+1.1 per cent).

- The most largest price falls were vegetables (-10.3 per cent), audio, visual and computing equipment (-6.3 per cent), electricity (-1.5 per cent), domestic holiday travel and accommodation (-1.5 per cent), milk (-4.6 per cent) and toiletries and personal care products (-2.3 per cent).

Is the result an indication that the fears of rising inflation are on solid ground? Answer: not really. I might be called bananas but I think the inflation rise (it is not a surge as the press is claiming) will be relatively short-lived for reasons I will explain.

The reaction of the currency markets was immediate because they assumed that the rise in the annual inflation rate would force the RBA to push up interest rates next week. I don’t think that will happen given how sluggish the overall economy is.

The following graph shows the Australian dollar-US parity (time is GMT) for today (up until when I was writing this – lunchtime). The sudden jump in the exchange rate – to establish the highest AUD-US parity since we floated the Australian dollar in 1983 – followed swiftly on the heels of the ABS data release. The AUD reached $US1.1063 just after the CPI figures were released but by the end of lunchtime I notice it has eased to $1.1036 (on Sydney prices). The AUD also appreciated by against the yen (by 0.6 per cent) in the aftermath of the data release.

This is the classic announcement effect that econometricians find interesting.

And what might you ask is behind this? We might consider this to be a banana-driven inflation! Yesterday, the Sydney Morning Herald carried an article (July 26, 2011) – Inflation perceptions go bananas – as a lead-up to the release of today’s CPI data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The title was in reference to the astronomical price of bananas at present (due to floods and cyclones).

The article predicted that the inflation rate measured by the annualised change in the CPI would come in around 3.4 per cent (essentially unchanged from the previous quarter) but that the CPI was poor measure of the underlying rise in the cost of living.

Staying in theme, today’s ABC News Report (July 27, 2011) carried the title – Dollar goes bananas on rising inflation.

Yes, the humble banana!

Trends in inflation

The headline inflation rate increased by 0.9 per cent in the June quarter translating into an annualised increase of 3.6 per cent for the year to June which is up from the March quarter of 3.3 per cent.

What does it mean for monetary policy?

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is designed to reflect a broad basket of goods and services (the “regimen”) which are representative of the cost of living. You can learn more about the CPI regimen HERE.

The ABS say that:

The CPI is a temporal price index for consumption goods and services acquired by Australian resident households. It is an important economic indicator, providing a general measure of price change … The principal purpose of the Australian CPI is to measure inflation faced by consumers to support macroeconomic policy decision making. This is achieved by providing a measure of household consumer inflation by the acquisitions approach.

There are various ways of assessing the general movement in prices depending on the purpose that the measure is being used for. The document I linked to above details some of the approaches. One of these approaches – the “acquisitions approach” – attempts to measure “household consumer inflation” and defines the basket of goods and services as “consisting of all consumer goods and services actually acquired by households during the base period.” The ABS use “market prices for goods and services” (including taxes etc) and make no imputations for “non-monetary transactions” (such as imputed rents). They also exclude “interest rate payments”.

So when the CPI increases by 0.9 per cent in a quarter we cannot deny that this is significant. But to see how significant we have to dig deeper and sort out underlying structural inflation pressures and ephemeral price facts. As the introductory summary shows the price rises are being driven largely by oil prices and food shortages arising from floods earlier in the year. It appears that the flood effect is diminishing given that the June quarter result was well down on the March 2011 outcome.

So while the cost of living has risen the implications for macroeconomic policy depend on a different measure of inflation. The RBA’s formal inflation targeting rule aims to keep annual inflation rate (measured by the consumer price index) between 2 and 3 per cent over the medium term. Their so-called “forward-looking” agenda is not clear – what time period etc – so it is difficult to be precise in relating the ABS data to the RBA thinking.

What we do know is that they do not rely on the “headline” inflation rate. Instead, they use two measures of underlying inflation which attempt to net out the most volatile price movements. How much of today’s estimates are driven by volatility?

To understand the difference between the headline rate and other non-volatile measures of inflation, you might like to read the March 2010 RBA Bulletin which contains an interesting article – Measures of Underlying Inflation. That article explains the different inflation measures the RBA considers and the logic behind them.

The concept of underlying inflation is an attempt to separate the trend (“the persistent component of inflation) from the short-term fluctuations in prices. The main source of short-term “noise” comes from “fluctuations in commodity markets and agricultural conditions, policy changes, or seasonal or infrequent price resetting”.

The RBA uses several different measures of underlying inflation which are generally categorised as “exclusion-based measures” and “trimmed-mean measures”.

So, you can exclude “a particular set of volatile items – namely fruit, vegetables and automotive fuel” to get a better picture of the “persistent inflation pressures in the economy”. The main weaknesses with this method is that there can be “large temporary movements in components of the CPI that are not excluded” and volatile components can still be trending up (as in energy prices) or down.

The alternative trimmed-mean measures are popular among central bankers. The authors say:

The trimmed-mean rate of inflation is defined as the average rate of inflation after “trimming” away a certain percentage of the distribution of price changes at both ends of that distribution. These measures are calculated by ordering the seasonally adjusted price changes for all CPI components in any period from lowest to highest, trimming away those that lie at the two outer edges of the distribution of price changes for that period, and then calculating an average inflation rate from the remaining set of price changes.

So you get some measure of central tendency not by exclusion but by giving lower weighting to volatile elements. Two trimmed measures are used by the RBA: (a) “the 15 per cent trimmed mean (which trims away the 15 per cent of items with both the smallest and largest price changes)”; and (b) “the weighted median (which is the price change at the 50th percentile by weight of the distribution of price changes)”.

While the literature suggests that trimmed-mean estimates have “a higher signal-to-noise ratio than the CPI or some exclusion-based measures” they also “can be affected by the presence of expenditure items with very large weights in the CPI basket”.

The authors say that in the RBA’s forecasting models used “to explain inflation use some measure of underlying inflation (often 15 per cent trimmed-mean inflation) as the dependent variable”.

The special measures that the RBA uses as part of its deliberations each month about interest rate rises – the trimmed mean and the weighted median – also showed moderating price pressures.

So what has been happening with these different measures?

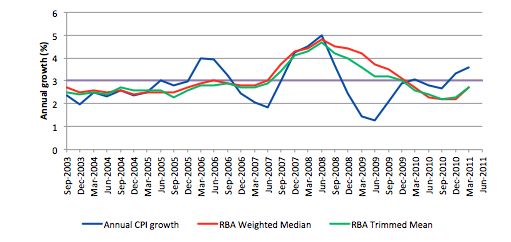

The following graph shows the three main inflation series published by the ABS – the annual percentage change in the all items CPI (blue line); the annual changes in the weighted median (red line) and the trimmed mean (green line). The horizontal purple line (at 3 per cent) denotes the upper bound of the RBA’s target range.

The annual growth in the weighted median rose to 2.7 per cent in the June 2011 quarter (from 2.2 per cent in the March quarter). The trimmed mean rose from 2.3 per cent in the March quarter to 2.7 per cent in the June quarter.

First, the RBA-preferred measures are still well within the inflation-targeting band of 2-3 per cent. So there is no justification for a rise in interest rates to follow today’s release.

Second, the upward movement in the June quarter was driven largely by volatile factors which I will discuss in more detail next. Inasmuch as there were no underlying price pressures (say from wages) operating I do not call this quarterly rise (which after all was a fall on last quarter’s result) a price spike or a surge. There is every reason to consider the factors that are driving the headline rate to be largely volatile and ephemeral (food prices and petrol).

The underlying outlook remains relatively benign and the data remains well within the RBA’s targeting range. The swaps market which provides some indication of what the traders think will happen to interest rates is still (when I looked at 14:02) thinking rates will fall over the next 12 months.

My conclusion – there is no case that can be made for an interest rate hike in the foreseeable future notwithstanding the opinions of some of the more gung-ho financial market commentators.

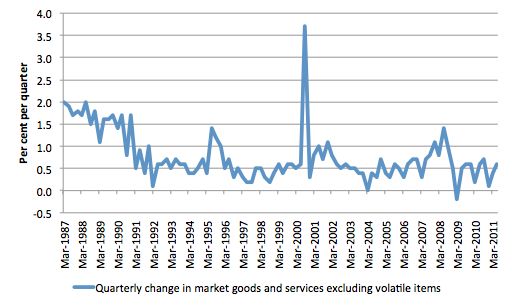

To put the result in perspective consider the following graph which is the quarterly change (per cent) in prices for market goods and services excluding volatile items from the March quarter 1987 to the June quarter 2011.

This series excludes Fruit and vegetables and Automotive fuel and Utilities, Property rates and charges, Child care, Health, Other motoring charges, Urban transport fares, Postal, and Education. So not only the likely ephemeral price items but also government-imposed charges which usually represent step increases in the price level rather than on-going price pressures.

There is no doubt that these non-market impulses can spark a wage-price inflation but that is another story and not relevant for assessing what today’s results mean.

Even the most cursory examination of the graph suggests that today’s data is hardly alarming and signalling an impending inflation spiral.

What is driving inflation in Australia?

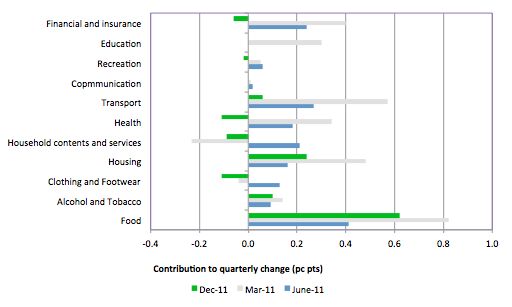

The following bar chart compares the contributions to the quarterly change in the CPI for the December 2010 (green), March 2011 (grey) and June 2011 (blue) quarters by component.

The ABS reports that for the June quarter, the most significant price rises were fruit (+26.9 per cent), automotive fuel (+4.0 per cent), hospital and medical services (+3.4per cent), furniture (+6.0 per cent), deposit and loan facilities (+2.1 per cent) and rents (+1.1 per cent).

If you consider the graph – it is clear that more items are now contributing to the underlying inflation outcome than say in December 2010. But the other point is that most of these components have reduced their overall impact on the headline figure.

In the commentary for the December quarter 2010 – There is no inflationary outbreak evident – the economy is slowing – I wrote that “we can see the start of the weather-related impacts on food prices here. That will get worse as the full losses to productive capacity in the farms arising from the floods is revealed.”

Those impacts consolidated in the March quarter and while still present in the June quarter have weakened. The fact that vegetable production is now rising again and prices are dropping quickly is evidence of that. The price pressures will further dissipate as the productive capacity of the farms arising from the floods is restored to more normal levels.

It is clear that food has been a significant contributor to the June quarter 2011 outcome.

The ABS said in relation to food:

The food group recorded an increase in the June quarter 2011. The most significant contributors were fruit (+26.9%) and restaurant meals (+1.3%). The rise in fruit prices was mainly attributable to an increase of approximately 138% in the price of bananas in the June quarter 2011 due to shortages created by Cyclone Yasi in February 2011. Banana prices increased 470% over the six months to the June quarter 2011. Vegetables (-10.3%) provided the most significant offset, due to favourable growing conditions.

That is why we are getting the “bananas did it” headlines. Take the food price rises out and you have a significantly different overall outlook. That is why I do not consider this to be an inflationary surge.

The other major contributor is petrol and these price movements are largely beyond the influence of the Australian economy. The problem is that each time there has been a surge in oil prices the world economy has recessed soon after.

The ABS said that:

Automotive fuel rose in January (+2.4%), February (+2.2%), March (+4.8%) and April (+1.4%), then fell in May (-0.1%) and June (-3.4%).

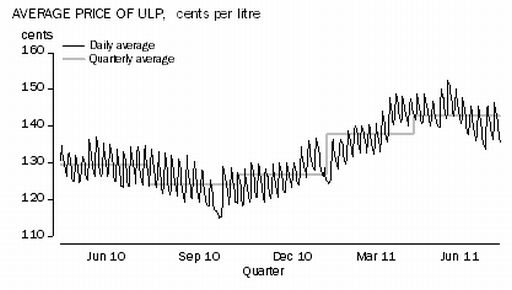

The ABS provided a very interesting graph which showed “the pattern of the average daily prices for unleaded petrol for the eight capital cities over the last fifteen months”. I reproduce that graph next.

The early part of the quarter was dominated by some hefty oil price rises but more recently there has been an easing. The OPEC barons are now much more aware of the damage that a recession can inflict on their revenues and tend to ease more quickly than say in the 1970s.

But there are two additional trends to consider. The non-OPEC oil producers will reach peak in the near future and the national composition of demand for oil (and energy in general) is shifting with the rise of China and India. While it is likely that the current surge in oil prices is ephemeral, the long-term trend in energy prices generally is up.

Please read my blog – Be careful what we wish for … – for more discussion on this point.

At present, there is no evidence that demand pull factors emanating from within Australia are driving the inflation trend.

Conclusion

The inflation rate has risen steadily this year mainly due to transitory factors such as natural disasters and external factors (petrol prices). Only the energy price issue is of concern. The farms damaged by the floods etc will be back into production before long and then the supply boost will see food prices fall sharply.

Related data shows there are no signficant generalised wage pressures in the economy at present. It is also clear that the overall economy is slowing and at least one major banks (and the swaps market) are betting on a fall in inflation. The retail sector is now probably in recession. I will write more about that another day because it introduces some interesting new developments as a result of the growth of the Internet.

The madness in Europe and the US at present is also conditioning a negative outlook.

That is enough for today!

I know that this is not directly related to what you said today, but I am really curious what is the position of MMT on NGDP targeting? Also given your inclination for full-employment based automatic demand stabilization (prefferably by fiscal policy), how would the government following MMT advices fare when facing supply shocks such as those in 70-ties? What measures can be used to differentiate between supply and demand induced recessions and what is the MMT position on former? Thanks.

JV, the only thing you can really do about a supply shock is find alternatives to supply. In the US for e.g. they went from Oil dependency to using natural gas and as best as I can tell from my own research Australia did the same.

On NGDP, I would imagine (and I could be totally wrong) that MMT in principle would oppose targeting an outcome for it as that is exactly what it is, it is an outcome not a policy variable. Ditto the budget.

I hope I answered some of your questions.

HOUSEKEEPPING: A few of us are now actively using the #MMT hashtag on Twitter for (of course) all things MMT. As MMT continues to expand its presence, we’re hoping that the #MMT hashtag might serve as a sort of central clearing house for links to the many articles now discussing (both positively and negatively) MMT, and whatever else of interest might pop up on same. Please join in. The more who use this, the better it will be.

P.S. And best of all, the hashtag’s free. We paid for it with money we created out of thin air. 🙂

Thanks Sennex for answer. I understand that supply shocks have to be solved by painful realignment of the economy, or in neoliberal newspeak it means that they are structural. What I’m curious about is that Mr. Mitchell is proponent of full employment (2% unemployment rate, everybody who wants a job has a job) as alpha and omega of public policy. If this goal is not met, that means that government has to start utilizing resources (tax cuts or direct spending) no matter deficits and/or inflation worries. While I agree that such policy makes sense in demand driven recessions (such as we have now), however it can be potentially disastrous during supply shocks. Or I may try to reformulate the question – how do you know what is the underlying “correct” level of unemployment at any moment that can be absorbed by additional nominal spending? Mainstream macro claims that such level is characterised by non-accelerating inflation ratio (NAIRU) – which I agree is bogus. However I am not that convinced that other extreme identified as “2% at all times” is good as well.

.

As for the NGDP targeting. If you follow the classical explanation of inflation targeting, namely that MV = PY and that V = constant and Y is always at full employment, in such world inflation targeting makes sense (especially with faith in NAIRU ). What NGDP targeting means is that we hold the whole right side of the equation as stable and growing at the trend level. Now the point is that it does not matter if the target is met by monetary of fiscal policy as long as it is met. What we have is a system which ensures that if demand is insufficient, the new money is created (either as a credit induced by lower interest or possibly as direct government spending) to fill this gap. And conversely, if for example inflation builds up in such level that NGDP shoots over its trend, the money would be destroyed automatically in similar fashion (interest hikes, tax increases/spending cuts) to compensate. While this system shares some weakness of inflation targeting, namely that it may support long period od underemployment – such as if yearly allowed NGDP growth rate is set as too timid from the long run, it does not share the problem I think stated in first part of the post – government trying to keep low unemployment during supply side recession.

JV

“how do you know what is the underlying “correct” level of unemployment at any moment that can be absorbed by additional nominal spending? ”

The Job Guarantee is the new unemployed.

If you think of it that way you see that during supply side shocks, private businesses go bust and people drop onto the Job Guarantee – which then expands automatically to cope.

JG is essentially what unemployment relief should have been in the first place.

@ J.V. Dubois

The alternative to rational policy in a severe supply shock is eliminationism. The people at the bottom, mostly in the Third World, die off. I consider the US approaching a Third World failed state now.

@J.V Dubois,

Not sure if this is what you are talking about about supply side shock, but Bill wrote about how MMT deals with supply side inflation in this blog entry: https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=13035

“how do you know what is the underlying “correct” level of unemployment at any moment that can be absorbed by additional nominal spending? “ Easy. The correct level is 0%, and no lower. The state should not employ dead, unborn or fictional people. Nominal spending is not constrained. Show up to the JG office. They give you a paid job as soon as you show up, even if it just waiting for a job. The JG demand determines the spending, not the spending determining the employment level.

However I am not that convinced that other extreme identified as “2% at all times” is good as well. Hard to argue that it is not good for the otherwise involuntarily unemployed.

The JG is a base, a minimum living wage. If supply shocks cause price rises and unemployment, it will be mainly of people with above JG wages. Their belt tightening lowers demand and inflation, while the work the JG engages in increases supply relative to the state of higher unemployment.

The actual JG work done may have to adapt to changing supply conditions, and the non-labor expenditures of the program controlled. But the point is that outside bizarre circumstances never seen, there is always going to be productive work to be done with whatever new supply constraints. Unemployment is always and everywhere a government decision to unemploy people. Why should it ever do this?

The JG is the least spending, the least stimulus, the least inflationary pressure – almost always none at all – for full employment. It is bottom-up; traditional investment-led demand-management “Keynesian” policies were more top-down and inflationary. As was seen during at the end of the full employment era with the oil shocks.

The usual time that nations employ “MMT” is during real wars. One can then socratically observe that everyone knows MMT already. Nobody uses mainstream superstitions when push comes to shove. Imagine – “The Enemy has just destroyed our strategic fnug mines, plants and reserves.” A supply shock. Does the nation then just let the fnug shortage work its way through the economy, creating inflationary pressure (semi-unavoidable, semi-beneficial) – Yes AND lingering unemployment of the workers in the fnug-related industries and elsewhere? NO. It employs the fnug workers on other things, particularly on grug production, which was what was used before the superior fnug became so plentiful and important.

(And of course see the blog Tristan linked to.)

@JV:

Abba Lerner talked about a Market Anti-inflation Plan, which i think MMTers should have a look at. Bill has mentioned an incomes-policy and the JG as a buffer stock, meaning what he calls “loose” full unemployment will be in effect at all times.

Some Guy excellent comment about wars and MMT. It looks like the ‘monetary illusion & madness’ is always destroyed in times of real danger. Then the money shenanigans go away, and only prices matter: there is full capacity utilization of the economy (including resources constraints) and no unemployment, unfortunately for the bad. Destroying the national debts of all sovereign nations would be an huge steep in the right direction, the next one being the implementation of JG.

About inflation, as long as housing is not included, al CPI indexes will be useless. This was a big trick on part of governments and banks in the age of huge inflation, and is an other trick now in the age of deflation (while certainly this deflation is asymmetrical because a lot of people goes into negative equity and real estate is not easy to liquidate.

JV, I’m only just back now but I believe others have successfully answered your questions. I would have said the same.

Thanks everyone for answers. However there are still some things that are unclear for me. First one concerns the Job Guarantee. As I understand, it is just enhanced version of social security. It may have positive effects for long-term unemployment prevention (work habit preservation and such), but from macroeconomic perspective in the demand side recession it is no different than unemployment insurance. You had people working for average wage and they suddenly recieve unemployment insurance/JG minimum wage. The point is that JG does not fully compensate for the lost income of the fired workers. So in case the demand shock is severe enough, we may still face plunge in the nominal GDP as both the real output and prices fall down.

.

Actually this thinking made me wonder about MMT position on NGDP targeting. To sucesfully prevent demand driven drop in economic activity, there still has to be some mechanism which fully compensates 1:1 for lost demand. And it does not have to be a JG. Actually for government it may be more useful to spend money on new infrastructure then to pay the same workers with needed skills a minimum JG wage for sweeping the already clean streets.

.

But then in supply-side shocks, it is possible that such government behavior will just put strain on already scarce resources. Or if I borrow words from “Some Guy” – if there is a shock to fnug production, what mechanism will ensure that government will not (illogically) respond to unemployment by building up fnug-dependent capacity instead of logical grug production capacity (governemnt does not have to look at ROI as private companies do)? Or as in real world, what if massive buildup of grug production as ordered by enlightened government in the midst of crisis unexpectedly causes shock in the market for frug? For real world example just look at biofuel example, when nobody from government regulators was able to predict its impact on food prices.

“The point is that JG does not fully compensate for the lost income of the fired workers.”

No it doesn’t and I don’t think it’s supposed to.

It puts a floor under everything to make sure that a contraction doesn’t result in destitution. But if there has been malinvestment or a supply side increase in prices, that still has to clear by somebody taking a real cut in standard of living. The JG buffer system determines where the real cuts will apply – which is a superior system to the current unemployment buffer.

Otherwise I would think you’re very likely to end up with stagflation.

You’re not eliminating the cycle here, just dampening its effects on people. People living high on the hog in unsustainable jobs spending unsustainable amounts will still come crashing down to earth eventually – whether those jobs are public or private sector.

And that’s the problem with the one lever approach of the monetarist school IMHO. They want to target one number and expect everything else to magically fall into place. It doesn’t appear to work like that. You end up with Minsky instability.

Ok, then I’m not that convinced that JG falls more into let’s say “standard political issue” then into macro realm. Actually in the country I live in (Slovakia) we have similar model when long-time unemployed may earn a so called “activation premium” for volunteering into public service jobs. However this program was complete failure as people who worked in this program have almost 6% less chance to find a job as those who did not participate. The main reason is that job seeking almost universally suffers once somebody subscribes. The fact that simple manual jobs did not increase the value of workers for modern labor market did no help too. However I still think that the concept could be implemented better, but then one has to be vary if the purpose is to keep people ready to be reemployed in private sector, or if the goal is to create hidden government overemployment in the name of the job security. As the final note I recently read this http://rortybomb.wordpress.com/2010/07/07/unemployment-insurance-1-raj-chettys-research-presented-at-epi/ very good article regarding the unemployment insurance vs subpar job acceptance – which is partially the same topic we have here.

As for the rest, I believe that monetarists are right in one sense. It is generally better to answer demand deficiency by inducing private spending. As long as the regulatory frame is of a good quality this I believe will generate better results in long term. That does not mean that there is no space for government activism, but I think that we should be much more careful prior to assigning too much discretionary power for governments to exploit crises to impose on us any policies no matter the costs.

But I see this as outside of general MMT scope. As I understand it, the theory just calls for government using either fiscal or monetary policy (or both) to prevent aggregate demand falls. So no matter what philosophical inclination you have there still remains logical answer – when and how much of this demand boost should we apply? Clearly pursuing full employment (e.g.JG) does not do the trick, as we can still have insuficient demand if too many workers use JG. So what then? How do we calculate proper size of our response, or even if we are to respond at all?

J.V.: “there still has to be some mechanism which fully compensates 1:1 for lost demand”

First, I don’t agree with this, at least not fully (only prolonged deflation may be harmful, and some minor deflation may be actually good). One of the big problems with deflation (drop in NGDP and prices) is unemployment. So JG works as a buffer stop of some sort against this problem. But then you have fiscal policy for this (government spending and/or tax cuts).

Also a minor note about JG: JG does not mean necessarily digging holes or working for the government, this is a matter of how you design programs: you can do it locally, collaborate with local corporations, NGO’s and charity, etc. The productivity of JG (which will help against inflation) is a matter of design, also because it never will outbid the private sector, as the demand picks up the market will be more efficient producing.

“But then in supply-side shocks, it is possible that such government behavior will just put strain on already scarce resources.”

Inflation? Government will have to target an inflation rate (just like now) and if prices increase then adjust. The same happens with private sector, we are and will continue to suffer cost-push inflation in the future and the market fails to use some resources effectively repeatedly. Eg. oil price would be much cheaper if people would use less SUV’s; that’s a totally irrational way of utilizing resources yet I’ve to suck it up (just because some rich people can affort it better).

In other words: I don’t thing this problem you point out will be worse with government investment or intervention in labour market; and the solution will have to be approached a lot of times by trial-and-error, just like as usual.