The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Accelerating inflation has to be out there somewhere … in the dark or somewhere

Today I was trawling through old issues of the now-defunct The Public Interest quarterly today and unfortunately stumbled on a recent issue of its successor National Affairs (Number 9, Fall 2011 edition) which carried an article – Inflation and Debt – written by Chicago economist John H. Cochrane – a known free market/anti-government commentator. It was one of those articles where the analytical framework was taken from some textbook rather than being ground in the realities of the monetary system and all the evidence pointed away from the major conjecture but the conjecture was still asserted as an inevitability. The title reflects the sort of wan, desperate need to find inflation despite vast volumes of excess capacity and zero wage pressures. Accelerating inflation has to be out there somewhere … in the dark or somewhere.

I thought the home page today of the British Office of National Statistics was a tell-tale. The headlines read:

Record public sector borrowing for August – Public sector net borrowing in August 2011 was £15.9 bn, around £1.9 bn higher than in August 2010. Net borrowing for year to date is £51.5 bn, which is £3.9 bn below the same period in 2010

UK productivity growth slower than G7 – In 2010, the between the UK and the US widened, and growth of UK productivity was below that of the G7 average.

Retail sales flat growth, mixed picture – Year on year, all retail sales saw no growth in the volume of sales between August 2010 and August 2011 and the value of sales increase by 4.7 per cent between August 2010 and August 2011.

Unemployment rate up to 7.9 per cent – The unemployment rate was 7.9 per cent, up 0.3 on the previous quarter. There were 2.51 million unemployed people, up 80,000 on the quarter.

Which tells you that it is losing external competitiveness and no generating the capacity for real wage increases, is not providing enough jobs and that demand deficiency is getting worse, and that the budget is moving further into deficit despite the fiscal austerity push.

As predicted, trying to run against the tide of the cycle by imposing pro-cyclical fiscal changes (contracting the discretionary component of the budget when the economy is in reverse) is not a very reliable way of reducing the overall deficit position. The reason is that the damage the austerity does to overall economic growth undermines the tax base and so the automatic stabilisers work against the discretionary intent.

In the ONS data – Central Government Finances, August 2011 I was interested to learn that taxes on income and wealth have fallen over the last 12 months while taxes on production have risen.

On the expenditure side social benefits are rising (as more people enter unemployment etc) but other current spending has risen. So it is a little unclear what is driving the rising deficit.

Conclusion: after showing signs of growth in late 2010 as a result of the fiscal stimulus provided earlier, the UK economy is being systematically undermined by its own government intent on imposing fiscal austerity which really means lower spending and income generation and higher unemployment in the months to come. Go figure.

Then I read what the Labour Opposition Chancellor proposed to do about it – as outlined in his 5-point plan – and I concluded that the British are somewhere between the devil and the deep blue sea – aka F$%4ed. You could never vote for Labour again under their current proposals which would only balls the place up further but then the current coalition is intolerable and are wrecking prosperity.

I will comment more about the Opposition’s five point plan another day. Bad luck if you live in Britain though if that is all you have to choose from.

Now to the article by John H. Cochrane in the current National Affairs. The National Affairs is the new marque for the old The Public Interest quarterly which morphed into the National Interest before assuming its current form. The publication has long been an outlet for “neo-conservative” views.

Apparently, Neo conservatives are about as gung-ho on free markets as true conservatives but emphasise “using American economic and military power to topple American enemies and promote liberal democracy in other countries”. The origins of the “movement” are disaffected US Democrats who no longer wanted to support the concept of the Welfare State and who were pro the invasion of Vietnam at a time when the mainstream Democrats were anti-war. So overall – conservative war mongers!

Cochrane uses the article to mount an inflation fear that he thinks is missing in the public policy debate. Interestingly, for a monetarist, he says that the current inflation phobia which stems from the changes to central bank balance sheets during the course of the crisis (dramatic rise in reserves) misses the main danger.

He says:

But these questions miss a grave danger. As a result of the federal government’s enormous debt and deficits, substantial inflation could break out in America in the next few years. If people become convinced that our government will end up printing money to cover intractable deficits, they will see inflation in the future and so will try to get rid of dollars today – driving up the prices of goods, services, and eventually wages across the entire economy. This would amount to a “run” on the dollar. As with a bank run, we would not be able to tell ahead of time when such an event would occur. But our economy will be primed for it as long as our fiscal trajectory is unsustainable.

Substantial inflation might “break out” in America in the next few years but it will not be because the US government’s deficit is larger than usual. It will be because spending growth outstrips the capacity of the economy to respond by increasing output.

Further, the type of dynamics that John Cochrane is suggesting are possible – a wage-price spiral – do not occur as quickly as a bank run. The latter are often very spontaneous events. Wages growth requires bargaining and contracting which is timely and transparent.

The other observation at this stage is that the higher than usual deficits in the US (and elsewhere) are symptomatic not causal. They reflect very weak private spending and massive pools of excess capacity (idle equipment and labour).

The output gap is so large in the US at present that if people do decide to increase their spending rate the economy would certainly respond in real terms.

The other point about this introductory position is that there is no way a reader can make sense of the argument because it is not grounded at all. All we read is “enormous debt and deficits” to which we say relative to what? or “intractable deficits” – what deficit is tractable? or “fiscal trajectory is unsustainable” – what is a sustainable fiscal trajectory?

In other words, there is no precision in Cochrane’s argument – it is just a howl against deficits because he is a free market economist who has to eschew public net spending as a matter of course.

Cochrane also realises he is pushing up hill. He notes that:

Many economists and commentators do not think it makes sense to worry about inflation right now. After all, inflation declined during the financial crisis and subsequent recession, and remains low by post-war standards. The yields on long-term Treasury bonds, which should rise when investors see inflation ahead, are at half-century low points. And the Federal Reserve tells us not to worry …

In other words, all the evidence is pointing away from an outbreak of accelerating inflation yet for a Chicago ideologue that is something that is impossible to undertand given the changes to the US Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet and the rising deficits. They just cannot believe what they are seeing and so conclude that their vision has failed them. There has to be an inflation threat because their models tell them there is. The models are never really questioned although that would be the first place I would start if all my predictions were wrong and systematically so over a lengthy period.

The first observation that Cochrane makes is that “serious inflation is most often the fourth horseman of an economic apocalypse, accompanying stagnation, unemployment, and financial chaos. Think of Zimbabwe in 2008, Argentina in 1990, or Germany after the world wars.” So we get the Wiemar and Zimbabwe card all in one sentence.

The nations mentioned cannot be held out as examples of to justify an argument of current vulnerabilities. Please read my blog – Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101 – for more discussion on this point.

But for Cochrane the “reason … is straightforward”:

Inflation is a form of sovereign default. Paying off bonds with currency that is worth half as much as it used to be is like defaulting on half of the debt. And sovereign default happens not in boom times but when economies and governments are in trouble.

The tying together “economy in trouble” with “government in trouble” is an ideological statement in most situations (bar EMU). Exactly what “trouble” might one conceive that the US government is in? Political – sure – the nation is being governed by idiots. Economic – sure – there is stagnation and entrenched high unemployment. Financial – never!

It is financial trouble that Cochrane is implying here although he is deliberately vague because he knows that once he set about specifying how a sovereign government such as the US which issues its own currency and only really borrows in that currency could actually ever be in “financial” trouble. By his own metrics – bond yields – he has earlier admitted they are low – even though this negates his central thesis that markets are fearing inflation.

Cochrane then said:

Most analysts today – even those who do worry about inflation – ignore the direct link between debt, looming deficits, and inflation.

Which links? There is a stock-flow link between net public spending and debt because the institutional arrangements applicable to the previous gold standard/convertible currency – debt is issued to private markets to match the net spending – have been maintained even though they are wholly redundant in a fiat monetary system.

But what is the link between deficits and inflation? There is no intrinsic link. There is an inflation risk embodied in all spending should it outstrip the productive capacity but continuous deficits can be run forever without triggering any inflation. To be clear – there is nothing special about government spending in this regard. All private spending carries an inflation risk.

What I found interesting about the article was that Cochrane eschewed the usual mainstream (monetarist) argument about inflation which is centred on the Monetarist “ties between inflation and money”. This is arguments that ultimately reflects the continued belief in the Quantity Theory of Money and focuses on the “Fed’s recent massive increases in the money supply will unleash similarly massive inflation”.

Cochrane claims the real risk is fiscal:

While the assumption of fiscal solvency may have made sense in America during most of the post-war era, the size of the government’s debt and unsustainable future deficits now puts us in an unfamiliar danger zone – one beyond the realm of conventional American macroeconomic ideas. And serious inflation often comes when events overwhelm ideas – when factors that economists and policymakers do not understand or have forgotten about suddenly emerge. That is the risk we face today.

It is actually an incredible article – full of assertion and implied statements.

First, what is an “unfamiliar danger zone”? When do we get into that zone? No information provided. Somehow large means danger. But if the government is solvent with $US1 of outstanding liabilities it is also solvent if those liabilities scale a thousand, a million, a billion, a trillion times. Noting of-course that we usually think of these things in terms of some scaler (such as percent of GDP) and the aggregates today are not that out of kilter with historical outcomes given the scale of the real downturn.

But there is no solvency danger zone for a government that issues its own currency. It can never go broke for financial reasons.

Second, conventional American macroeconomic ideas are better forgotten. They have demonstrated their lack of capacity to explain why the world has entered this crisis and how we might all get out of it. The application of conventional American macroeconomics would have led to predictions of rapidly rising interest rates and accelerating inflation by now. The facts tell us otherwise.

Third, statements like “serious inflation often comes when events overwhelm ideas” and “factors” that “suddenly emerge” are all throwaway items without historical clarification or dimension.

In the interests of time, I now jump to his main argument – that inflation is a fiscal issue. He motivates this discussion by observing that “the correlation between inflation and the money stock is weak, at best” which would appear to negate the applicability of the Quantity Theory of Money – a central tenet of Monetarism.

He has an excuse for this breakdown in the M -> P causality which I will skip (it relates to fluctations in money demand and liquidity traps – in other words, a special case).

He then says:

You don’t have to visit right-wing web sites to know that our fiscal situation is dire. The Congressional Budget Office’s annual Long-Term Budget Outlook is scary enough. Annual deficits are now running about $1.5 trillion, or 10% of GDP. About half of all federal spending is borrowed. By the end of 2011, federal debt held by the public will be 70% of GDP, and overall federal debt (which includes debt held in government trust funds) will be 100% of GDP.

At that point I yawned and wonder how Cochrane approaches the situation of Japan which is way out of this ball-park of aggregates (on the “danger danger” side of Cochranes danger zone – whatever defines it).

To read that the US “fiscal situation is dire” you only have to visit WWW sites of organisations, commentators who have not yet worked out the operational characteristics of a fiat monetary system. They require an education. The right-wingers and the left-wingers fall into the same trap – of applying the principles that government public finance in the convertible currency system – by which governments had to issue debt to cover spending above tax revenue – to a fiat monetary system.

A sovereign government is never revenue constrained in a fiat monetary system because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. It taxes and issues debt for reasons unrelated to any need to fund its spending. It patently doesn’t have to fund that spending.

The CBO is comprised of neo-liberal mainstreamers who still operate in the convertible currency paradigm. That ended in 1971.

All that the data that Cochrane quotes above tells me is that the US must be in a particularly nasty crisis where private spending must have collapsed (reducing the tax base) and welfare spending has increased. It also tells me that 30 per cent of federal debt in the US is held by the federal government itself which, in turn, tells me that there are crazy institutional arrangements in place.

Government lending to itself when it can spend in US dollars whenever it likes. It doesn’t get much crazier than that. I understand the development of these institutional arrangements and why they survived their redundancy after Bretton Woods collapsed. One word – ideology. Two words – neo-liberal. Several words – the desire to constrain government activity because of a misguided belief that private is good and public is bad.

After telling us that public liabilities will balloon and explode (more of that scary prose to garner effect), Cochrane claims that “(t)hree factors make our situation even more dangerous than these grim numbers suggest”.

All three factors are irrelevant and I will skip a detailed discussion. They are:

1. “There is only a “safe” ratio between a country’s debt and its ability to pay off that debt” and the US can no longer has “the power to pay off and grow out of its debt”. Question: When has the US ever “paid off” its debt? Although I don’t advise it, the US government could pay back all its debt from today as it matures. It always hat an “ability to pay”. Cochrane just asserts that they have lost it. I suggest he has been reading too much R&R and has become confused.

2. The US government has guaranteed a number of other institutions (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, etc) which might explode into new debt. The US government can honour all its liabilities whether direct or indirect as long as they are denominated in US dollars.

3. Americans are getting older and will require more health care which will generate “terrible projections of future deficits” which puts America in a “worse situation than Ireland or Greece”. Once a commentator conflates a fiat monetary system (US) where the national government is sovereign with a non-fiat system (EMU) where national governments are not sovereign you realise they have not taken the time to understand the difference. There is no meaningful comparison between governments operating across the two monetary systems.

Further, the ageing society is not a fiscal issue. Please read my blog – Democracy, accountability and more intergenerational nonsense – for more discussion on this point.

Cochrane then links “fiscal problems” to “a debt crisis” because he claims the private markets will eventually stop funding the government. If the bond tenders ever generated spiralling yields which were considered undesirable (rather than unaffordable – the US government can always afford anything) then I am sure there would be legislation to unlock more of the potential that a fiat monetary system provides the government.

But the main link he wants to make is between the deficits and inflation.

I thought this was a good place to start:

Why does paper money have any value at all? In our economy, the basic answer is that it has value because the government accepts dollars, and only dollars, in payment of taxes. The butcher takes a dollar from his customer because he needs dollars to pay his taxes. Or perhaps he needs to pay the farmer, but the farmer takes a dollar from the butcher because he needs dollars to pay his taxes. As Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations, “A prince, who should enact that a certain proportion of his taxes should be paid in a paper money of a certain kind, might thereby give a certain value to this paper money.”

So it is the demand that taxes have to be paid in the currency of issue that gives that currency value. Otherwise the fiat currency is just worthless bits of paper.

But after that promising start, Cochrane then says:

Inflation results when the government prints more dollars than the government eventually soaks up in tax payments. If that happens, people collectively try to get rid of the extra cash. We try to buy things. But there is only so much to buy, and extra cash is like a hot potato – someone must always hold it. Therefore, in the end, we just push up prices and wages.

So you detect here some very sneaky assertion and deliberately confused temporality.

First, inflation does not “when the government prints more dollars than the government eventually soaks up in tax payments”. A government can run a continuous deficit forever without incurring any inflationary pressures. As long as the deficits are providing aggregate demand growth commensurate with the real capacity of the economy there will be no inflation (and really what he is talking about is accelerating inflation).

Under what conditions might that apply? Answer: when the non-government sector is desiring to net save in the currency of issue. If we disaggregate the non-government sector into external sector and private domestic sector then a number of situations could be consistent with that statement. Most typically, an economy with an external deficit and a positive saving desire by the private domestic sector will require on-going deficits to fund growth.

Second, clearly, if the economy is at full employment and “people collectively” reduce their saving desire and “try to buy (more) things” then “there is only so much to buy” and the aggregate demand pressures will put pressure on the price level. That is obvious but not a risk that is exclusive to public spending.

Cochrane also falls into the trap of believing that “selling bonds” reduces the inflation risk involved in public spending:

The government can also soak up dollars by selling bonds. It does this when it wants temporarily to spend more (giving out dollars) than it raises in taxes (soaking up dollars). But government bonds are themselves only a promise to pay back more dollars in the future. At some point, the government must soak up extra dollars (beyond what people are willing to hold to make transactions) with tax revenues greater than spending – that is, by running a surplus. If not, we get inflation.

The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy which introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. Cochrane fails to acknowledge that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations – that is, bank accounts are credited.

Mainstream thinking asserts that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target. Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance. So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk.

Cochrane then suggests that if bond investors decide they don’t want to hold that volume of financial assets any more and spend the proceeds of a bond sale instead this will be inflationary:

As the government pays off maturing debt, the holders of that debt receive a lot of money. Normally, that money would be used to buy new debt. But if investors start to fear inflation, which will erode the returns from government bonds, they won’t buy the new debt. Instead, they will try to buy stocks, real estate, commodities, or other assets that are less sensitive to inflation.

If and if.

But note, if the private spending increases, the budget deficit will decline and keep declining as the private spending growth accelerates. I often give talks to business people and I know at the outset they are antagonistic to deficits (as an ideological statement) unless they are direct beneficiaries (as a practical statement).

So I say to them that if they don’t like the current size of the deficit then they are empowered to deal with it. They look somewhat lost before I give them the solution – spend more yourselves.

Once again let us be clear – the only risk embodied in spending is inflation – public or private spending together. If private spending growth became robust and pushed up against the inflation barrier then the government has a choice – cut private spending via higher taxes or cut public spending. There is no inevitable inflation plank the government has to walk if it has been supporting aggregate demand growth at a certain rate and private spending accelerates and threatens inflation.

Simple solution – cut spending (public or private).

Just as Cochrane failed to find any “correlation” between monetary growth and inflation, he would also find no evidence for his claims that budget deficts of any size ultimately cause inflation. There is no credible research evidence that suggests that budget balances are related to rising inflation then hyperinflation.

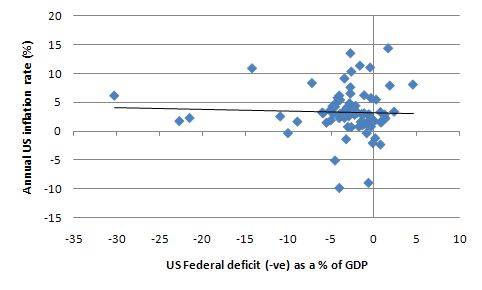

Consider the following graph which uses budget data from the US Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and CPI data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics from 1930 to 2011. It shows on the x-axis the US federal budget deficits as a per cent of GDP (negative is a deficit) and the annual inflation rate in the US on the vertical axis. The black line is a linear regression relation between the two time series – which indicates no relationship at all (effectively flat).

The picture doesn’t alter much if you use lagged inflation rates (1-year, 2-year) to capture “build-up” effects of past budgets on price inflation. There is no significant relation at all.

It also doesn’t matter if you plot inflation (the percentage change in the price level) or accelerating inflation (the change in the inflation rate) on the vertical axis. There is no relationship per se.

This conclusion is in accord with the standard research on the topic. It contradicts the mainstream theoretical claims that appear in the Cochrane article.

I also note that since 1930 there have been federal budget deficits 85 per cent of the time in the US and no accompanying secular trend towards accelerating inflation and the destruction of the value of the US dollar over that period.

Conclusion

The point is that budget deficits might be inflationary if they push the nominal aggregate demand in the economy beyond the real capacity of the economy to respond by increasing real output. Under certain conditions – which are definitely in place at present – a rising budget deficit will not be inflationary.

And for the unemployed a rising budget deficit will provide them with enhanced real capacity to consume because jobs will become more plentiful.

Fiscal austerity will increase the real output gap and drive up unemployment and the decline in aggregate demand leads to a slower rate of inflation and, ultimately, deflation (falling prices).

The major problem facing the US is that chronic output gap and concomitant high unemployment. That signals to me that the budget deficit is too small relative to the economy (which means other spending aggregates).

That is enough for today!

As a Brit I await your analysis and comments on the Ed Balls up policies with interest. The Blair inheritance of professional sound bite politicos goes on ( note to self use hands for emphasis) .

Regarding:

“[The U.S.] is governed by idiots.”

I have ongoing discussions with friends and family about this – the “are they stupid or are they evil?” conversation. I know that many politicians and (especially) media people are indeed, and often profoundly, stupid. They are actors. Politics in America is part of the entertainment industry – a branch of the reality-T.V. genre. These people win election by sounding completely sure that the absurdities they give voice to are nuggets of pure truth. The absurdities are provided by handlers and operatives, after being selected by market research analysts from the storehouse of corporately-funded think-tank material.

But what about the real intellectuals, like Professor Cochrane? He’s not stupid. Summers, Geithner and Bernanke aren’t stupid. And it’s obvious that they know perfectly well that austerity is worsening the crisis and destroying ordinary peoples’ lives. They just have to couch it in acceptable mainstream language and hem it in with a lot of verbiage that implies that the conventional theoclassical theory is still valid, but we’re in such a “perfect storm” we have to improvise a little.

Such people don’t pass muster in my book as innocent “idiots”. For them, I come down on the side of “evil”.

Nice article – totally agree; I came across this article on another website recently being recommended as something everyone “must read” but could tell from the start it was just a neoliberal scare/propaganda piece.

Unfortunately I am British and feel that we have no choice between three neoliberal parties – all intent on running budget surpluses either within the next five or ten years. I find it ironic and kind of amusing – although as it is likely to cause great economic hardship in the UK my laugh is more nervous than anything else.

Dale:

“are they stupid or are they evil?”

Yes.

Here in the States the plan for inflation is to withhold the fiscal lever until after we’ve liquidated our ability to produce anything. Then it’s a sure bet!

Regarding stupid or evil, consider a third option, which is that they are blinded by faith, true faith, in free market/invisible hand dogma. This is in part a reflection of the selection process required in to get established in academia (with heterodox dissenters basically expelled to the equivalent of Siberia in academia), and partly a reflection of what is required to maximize their own net worth while working in academia – that is by providing the necessary ideological wool to pull over the eyes of policy makers, politicians, and citizens. They are, in every sense of the world, theologians trying to enforce a collective trance in favor of neoliberal nostrums, just so the top 1% can walk away with nearly all the spoils of the economic war (particularly on natural and social capital) and throw the craftier mainstream priests a big enough bone.

My own comments about how inflation is so much less destructive than unemployment got me thinking about the stagflation of the 1970s. When you get right down to it the inflation part of it was really nothing to worry about. Yet the press carried on about as if the world was comming to an end.

At that time, I was barely a teenager, I had no idea how treacherous those involved with running a nations finances can be. Now I am more aware and I have to wonder if the whole period of stagflation was not only a planned event but an event planned for a long term purpose. A purpose that did not have anything to directly do with making someone more profits but for creating a historical narrative to give future generations less choices so that the choices available would be the ones that were favored by people unlike me.

My own comments about stagllation above got me thinking about the events of Watergate which occured at the beginning of the period of stagflation. Yes it is true that Watergate was a political scandal and not an economic one. But if Watergate was not really a scandal that was uncovered but a scandal that was manufactured with years of forethought it gives us an indication of the type of war that real leftists are fighting to take control of society and this planet from shallow minded egg heads.

For just a bit of background it has been asserted that very important events of the past decades have been completely misrepresented from the get go and therefore completely misunderstood.

As examples we can start with WW2 then move on to the Suez crisis followed by the Israeili attack on the USS Liberty, then the Clinton impeachment scandles, and lastly the road to war in Iraq. To be more specific the western allies prolonged the war against Nazi Germany by not taking the obvious and super super super easy steps of cutting off the supply of critcal raw material to Germany from Sweden, Spain, Portugal, and Turkey. They did this because at first they were actually hoping for a Geman victory against the USSR. After 1942 they just wanted the Nazis to inflinct as much damage on the USSR as they could. Yes of course the western allies gave some aid to the USSR, that was just plan B, cover thier asses, in case plan A failed. Then we have the Suez crisis in which the Europeans did not have any intention of keeping the Suez Canal. The whole point of the charade was to make it appear as if the France, the UK and the US were actually persuing seperate agendas when in reality their agendas have been coordinated since WW 2. The other nations of Europe are in on it as well. What is not known is how much of this European collaboration is driven out of real support and how much might be driven out of coercion. For example if you do not support this plan there will be a terrible accident in a major city in your country that will kill thousands. The next clear example of a disinformation campaign is the attack on the USS Liberty. This was clearly not an accident as claimed. The historical evidence for that is now overwhelming but forgotten. It was the biggining of a disinformation campaign to make it appear that the AiPAC has as much control over US foreign policy as the NRA has over personal weapons policies. Then we have the Charade of the Clinton scandals that lead to his impeachment proceedings. These were nothing more than a disinformation campaign to cement the idea that the American Democratic Party and the Republican Party are actually competing parties. Now this is not to say that Senator Sanders is a knowing collaborator.

It is to say that many people including Senators are manipulated. Then we have the obviuos conspiracy to invade the Middle East which huge numbers of people still believe was an honest mistake.

So if any of that makes any sense to you, and since it does make sense to me, it does not seem all that far fetched that not only was Watergate scripted well in advance, but that Nixon even volunteered for the staring role as the first President to be resign. The purpose of this charade could have been to create a narrative that we live in a Nation of ACCOUNTABILTY. The Clinton escapades could have also been to reinforce that idea.

An implication of this world view is that the President of the USA is not the leader that he is made out to be but that actuall leadership rests somewhere in the military industrial complex. An organization such as the CIA with it access to such vast amounts of information and money would have to capabilty to manufacture history.

Now here is what is really important. If this assessment is true then I think that a person should ask themselves if the stratagies and tactics that have been used by the left to try to prevent the manufactured negative outcomes that are being handed to us by those who hold power NEED TO CHANGE. If so how can such change be coordinated with out always being two steps behind those that create the chaos?