I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Ignorance undermining prosperity

I gave a talk about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) today at a workshop on Stock-Flow consistent macroeconomics organised at the University of Newcastle by the economics group here. While I hold the research chair in Economics at this university I am not formally part of the economics group – my affiliation is with my research centre (CofFEE) which stands outside the Department/Faculty structure. So it was good to interact with the economics group. It is coincidental because the things I was talking about were being played out in the US and elsewhere (for example, Greece). The US conservatives are now pushing hard for a balanced budget amendment to the US Constitution. If they understood economics they would never consider doing that. If they succeed they will undermine US prosperity forever. It is a case of ignorance undermining prosperity which really describes a lot of what is going on at present in the public debates.

The news is that the US Republicans are once again demonstrating their lack of responsibility as political leaders. They walked out of budget discussions surrounding the negotiations about extending the debt ceiling and the House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-VA) today issued a statement “regarding House consideration of a balanced budget amendment”.

I will come back to that in the context of today’s talk.

But first, today (given time differences) is also notable because the University of Chicago closed the highly controversial Milton Friedman Institute after only three years in operation in what is an embarrassing retreat for them. The press release waxes lyrical about the new venture (a merger with an existing but smaller Becker Center but the closure is humiliating for the conservatives associates with the MFI.

Why was this merger necessary? University of Chicago is silent on that front. It seems that Gary Becker (the neo-classical human capital theorist who doesn’t understand that labour (the flow of services) is not the commodity bought in the labour exchange) has supplanted Mr Freakonomics (Steve Levitt the former Director of the Becker Center) and Lars Hansen the former MFI Director has been pushed down the hierarchy (now Research Director of the new centre).

The MFI has been the subject of staff petitions opposing its existence given the role that mainstream economics of the type championed by Milton Friedman himself played in the financial crisis and the poverty of the paradigm in addressing the crisis once it occurred. You will laugh at this statement (issued June 1, 2010) from Hansen defending the MFI against the petitioners.

Here is a Chronicle of Higher Education report that backgrounds the controversy. The news from those that opposed the MFI is that the University of Chicago has had trouble raising funds to support the institute partly because of the “declining value of the Friedman name and reputation” (severely compromised one might say by the global financial crisis) and also has been severely embarrassed by the campaign pointing out the flaws in the decision to create such a centre in the first place.

Anyway, good riddance.

But talking about embarrassing developments, come in Mr Cantor!

The Balanced Budget amendment would change the US Constitution such that the US Congress would have to balance the budget each year. The goal to keep the US public debt “in check”.

In his press release (linked above) Eric Cantor described the move as a “common sense measure” which will “get our fiscal house in order”.

The reality – RIP America.

The BB bill was approved last week (on June 15, 2011) by the House Judiciary Committee – which is sometimes referred to as “the lawyer for the House of Representatives because of its jurisdiction over matters relating to the administration of justice in federal courts, administrative bodies, and law enforcement agencies”. The Committee considers legislation that “carries a possibility for criminal or civil penalties”.

The Committee voted 20-12 for the balanced budget amendment proposal. Here is a Transcript of their deliberations. It would have a comical air to it if it wasn’t so tragic.

You read statements like this:

In fact, as written, this bill would cut total funding for non-defense discretionary programs by approximately 70 percent in 2021, by more than $3 trillion over 10 years

And:

… in balancing the budget, we will have to find savings in a variety of government programs, and that discussion should include Medicaid. Social Security, Medicaid and other government social programs will be helped, not hurt, by a balanced budget amendment. If the Federal Government is crippled with debt, it won’t be able to fund Medicaid or other government programs.

And:

… I think it is unfortunate that the Medicare issue is being used to distort this debate … But the truth is Medicare, Social Security, this country itself is at risk unless we change our budgetary and our fiscal habits … Mr. Goodlatte has put the balanced budget amendment here before this committee to remedy that situation

And:

The problem is you can’t repeal the laws of arithmetic. The fact of the matter is Medicare is going broke

And in the Statement of Judiciary Committee Chairman we read:

America cannot continue to run huge federal budget deficits. Financing federal overspending through continued borrowing threatens to drown Americans in high taxes and heavy debt.

Members of Congress on both sides of the aisle recognize this problem.

According to President Reagan, “Only a constitutional amendment will do the job. We’ve tried the carrot, and it failed. With the stick of a Balanced Budget Amendment, we can stop government squandering, overtaxing ways, and save our economy.

QED.

RIP, USA.

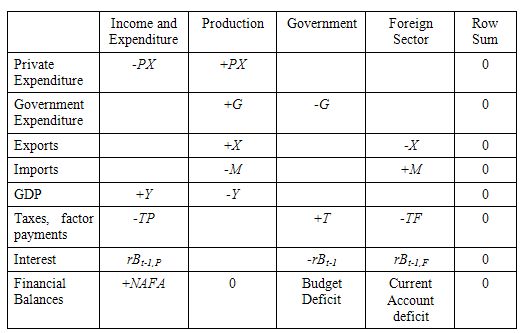

The workshop talk I gave today examined fiscal austerity from within a stock-flow consistent framework with MMT underpinnings. You can start with this simplified transactions matrix which is a particular view of the National Accounts. I explain that framework in considerable detail in this blog – Stock-flow consistent macro models.

Here, Gross Domestic Product, Y, is equal to Private expenditure, PX, plus government expenditure, G, plus exports, X, minus imports, M. The ROW account reveals that imports minus exports, transfers paid and interest received by the external sector, TF, equals the current account deficit.

Every item in the Production (GDP) account is matched by a corresponding negative entry in some other column. Taxes net of transfers are received by the government who pay interest on outstanding debt (B).

Net property income, taxes and transfers, TF and TP, are paid by the external and private sectors, respectively.

The final row totals reveal that the Budget deficit (or public sector net borrowing) equals the private net acquisition of financial assets, NAFA (private savings less investment) minus the external surplus (or plus the deficit).

The last row expresses the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations which is another “view” of the National Accounts. The sectoral balances provides a first-line reality check against some of the propositions that are abroad in the policy debate.

Sectoral of financial balances relate to total receipts less total outlays of the three sectors – government, external and private domestic.

You have seen this accounting identity for the three sectoral balances before:

(G – T) = (S – I) – (X – M)

National income adjustments in response to aggregate demand shifts ensure this relationship between the three sector financial balances always holds.

From the perspective of a stock-flow consistent approach to macroeconomic modelling outlined above, the fundamental accounting identity states that government savings (surplus) or tax revenue net of government spending and payment of interest on bonds is equal to the non-government sector’s dis-saving.

If (G – T) > 0 (that is, a budget deficit) then the sum to the right-hand of the equals sign (the non-government balance) must be in surplus and vice versa.

The term (S – I) equals total private domestic saving and (X – M) or net exports represent the net savings of non-residents. That has to hold as a matter of accounting.

As I noted in the talk, an understanding of this framework produces four incontrovertible facts.

- If budget deficit (as a percent of GDP) is less than the external deficit (as a percent of GDP) then private domestic sector will be in deficit.

- If budget deficit (as a percent of GDP) equals the external deficit (as a percent of GDP) then private domestic sector is in balance.

- If budget deficit (as a percent of GDP) is greater than the external deficit (as a percent of GDP) then private domestic sector is in surplus.

- If the external sector is in deficit, then a budget surplus or a balanced budget is always associated with a private domestic sector deficit.

These are accounting realities and but require a deep understanding of the operations of the monetary system and the way the macroeconomy works to interpret their movements and predict their future path.

So rather than mis-use the sectoral balances a solid theoretical grounding is required to augment the accounting consistency.

MMT is an integration of that theory with the national accounting and that makes it unique in the field of macroeconomics.

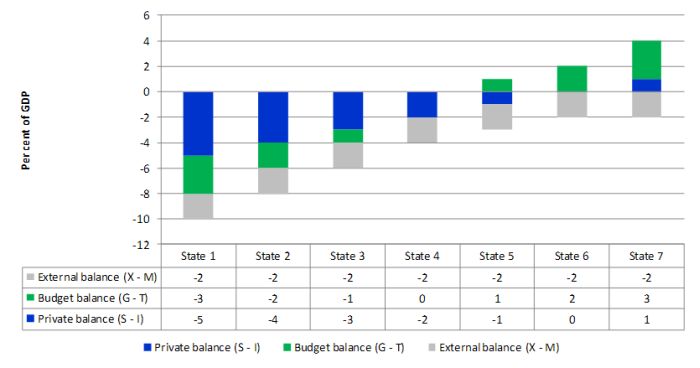

For a nation running an external deficit, the following graph (and data table) show the options which would exist depending on public and private spending decisions.

The last three cases (States 5 to 7) are budget deficits of increasing size (relative to GDP). It is only when the budget deficit is greater than the external deficit that the private domestic sector can save.

The earlier States show differing private domestic deficits. From a stock-flow perspective, we know that the flow (the private deficit) manifests in stock form as an increasing indebtedness. A growth strategy that relies on the private sector increasingly funding its consumption spending via credit is unsustainable.

Eventually the precariousness of the private balance sheets becomes the problem and households (and firms) then seek to reduce debt levels and that impacts negatively on aggregate demand (spending) which, in turn, stifles economic growth.

Today I talked about how the public debate that has led to fiscal austerity being centre-stage began by recognising that too much private debt led to the crisis.

The proponents of fiscal austerity then have convinced us that the real problem is that the private debt crisis has morphed into a public debt crisis.

Fiscal austerians argue that we need to reduce debt per se. That is only possible if if the external surplus is large enough. Otherwise, if you attempt to achieve that stage via fiscal cutbacks the policy strategy will undermine employment and growth. The upshot is that the budget deficit is likely to rise because of the slowing economy will undermine tax revenue.

The problem is that once you comprehend the sectoral balances you will soon realise that this is logically impossible as a global solution. Not all countries can run external surpluses.

The striking aspect of the public debate is that an awareness of this logical inconsistency is low to zero (apart from MMT types).

There is an alternative interpretation of-course: the fiscal austerity proponents know damn well what is going on but are just intent on finishing off the neo-liberal program of privatisation, welfare cutting and deregulation that the financial crisis rudely interrupted.

The irony that Stage One of the neo-liberal program led to the crisis in the first place escapes the conservatives. The Balanced Budget crew in the US are oblivious to the inconsistencies of their approach in the same way.

Even the so-called “progressive” who advocated what they think is a reasonable “balance the budget over the business cycle” rule fall into logical inconsistencies when they also argue that the driving force of the crisis was the exploding private debt.

If the government balances the budget over the cycle as they desire then the income adjustments that occur will always force the private sector into deficit over the business cycle equal to the external deficit. All nations cannot enjoy external surpluses and most have deficits.

External deficits are good as long as domestic policy is focused on maintaining high employment levels and providing support to demand to allow income growth to deliver the appropriate level of saving.

A stock-flow understanding tells us that in the “balance the budget over the business cycle” case, the progressives would be forcing the private sector into increasing indebtedness overall, exactly the problem they connected to the crisis in the first place.

Again, the sectoral balances provide a quick reality check to evaluate these sorts of propositions.

I then examined three case studies: Greece, the UK and the US to check what the implications of the fiscal austerity would be over time once we integrated a theoretical understanding of how national income is determined (MMT) and economic projections provided by the IMF and other bodies. I also modelled the Tea Party budget plans (budget deficit 2.2 percent of GDP by 2015).

The overwhelming conclusion that you reach once you simulate various projections and marry actual data that has been generated since the forecasts is that the fiscal austerity programs will drive the private sector into further debt (to support growth) or kill growth altogether. The latter is more likely given that the demand for credit at present is very low and the private domestic sector “players” are seemingly loathe to borrow again until they stabilise their already precarious debt levels (legacies of the last credit binge).

The British situation is very interesting and I covered it in this blog – I don’t wanna know one thing about evil (a great song by the way).

In that blog I documented some research I did in April 2011 digging deeply into the less publicised supplementary documents supporting the 2011 British budget. My talk today focused on the sheer cant of the British government in first claiming that:

Over the pre-crisis decade, developments in the UK economy were driven by unsustainable levels of private sector debt and rising public sector debt. Indeed, it has been estimated that the UK became the most indebted country in the world … Within the financial sector, the accumulation of debt was even greater. By 2007, the UK financial system had become the most highly leveraged of any major economy … This model of growth proved to be unsustainable.

And then projecting a growth strategy on a very optimistic net exports outlook and private consumption growth as the public sector contracted. I noted that the net exports data released since the Budget have already fallen well below the growth forecasts.

The Budget also estimated that the fiscal austerity program would lead to negative real household disposable income in 2011 and very low growth in the following years of the forecast horizon (to 2015). The fact is that the net exports growth assumed will not drive growth sufficiently and so the forward projections require a very strong recovery in household consumption.

Digging deeper into more obscure documents that have not been discussed in the public arena in any coherent fashion you find that the Office of Budget Responsibility (a division of the British Treasury) predicts the following:

Our March forecast shows household debt rising from £1.6 trillion in 2011 to £2.1 trillion in 2015, or from 160 per cent of disposable income to 175 per cent. Essentially, this reflects our expectation that household consumption and investment will rise more quickly than household disposable income over this period. We forecast that income growth will be constrained by a relatively weak wage response to higher-than-expected inflation. But we expect households to seek to protect their standard of living, relative to their earlier expectations, so that growth in household spending is not as weak as growth in household income. This requires households to borrow throughout the forecast period.

So the record levels of private sector debt caused the crisis yet the British government’s fiscal strategy is predicated on even greater levels of private debt.

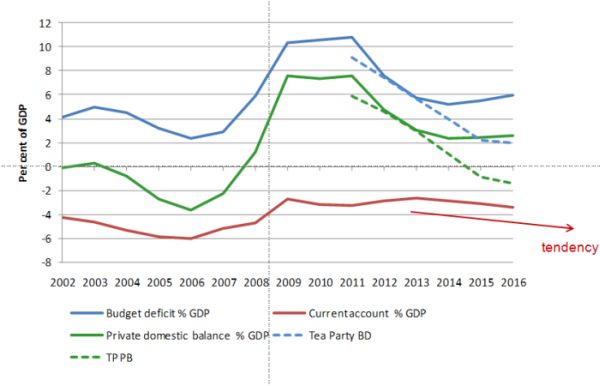

When it comes to the US a similar story can be told. The following graph shows the actual sectoral balances for the US from 2000 to 2010 augmented by the April 2011 IMF World Economic Outlook projections to 2016 and the dotted lines represent the Tea Party ideals.

If you examine the US sectoral balances since 1952 (see this blog – In policy you have to wish for the possible) you will see there is a tendency for the current account balance to decline as a percent of GDP. That is a good thing for the US because it means they are able to get more real goods and services for a given real resource sacrifice to exports.

But it requires domestic spending to ensure that the drain on aggregate demand coming from the negative external contribution is offset. The IMF projections which more or less reflect the fiscal austerity debates have the budget deficit slowly falling (via growth mostly) but that also means (given the external trajectory) that the private domestic balance is heading to the zero line.

If you model (roughly) the Tea Party proposals which (if you can make any sense of them) seem to target a budget deficit of 2.2 per cent of GDP by 2015 and the external sector follows the IMF trajectory, which is probably optimistic (I predict a widening external deficit), then the private balance would be in deficit by 2015 if the budget aims were realised.

I thought the problem was too much private debt!

This sort of thinking can expose the contradictions in the public positions. At present, the private sector in the US is now firmly in saving mode as the combination of entrenched joblessness, threat of job loss and the overhang of huge private debt levels demand caution. This spending withdrawal by the private sector has reduced the external deficit (as import growth declines) and forced the budget into increasing deficit.

If the US government had have resisted that dynamic and tried to maintain a lower deficit by countering the automatic stabiliser component (falling cyclical tax revenue and increased welfare outlays) with discretionary spending restraint then the US unemployment rate would have been much higher than it already is.

The current agenda which is being followed by both main parties will only bring the deficit down as a percentage of GDP while the private domestic sector is intent on reducing its debt exposure at the expense of a significant decline in economic growth.

The current policy agenda being pursued by both sides of politics will reduce economic growth and pit the automatic stabilisers (pushing a rising deficit) against the discretionary cuts. What most commentators do not recognise or admit if they do is that the private spending (and saving) decisions are very powerful and the government cannot really run counter to them.

The appropriate role of government is not to try to force a lower deficit when there is such entrenched unemployment and no demand-pull inflation. The correct policy response in this environment is to accommodate the private spending plans to ensure that there is sufficient aggregate demand to propel growth. That suggests in the current situation that the budget deficit has to rise.

The private sector has to reduce debt which in the current climate (external deficits) and institutional arrangements (government issues debt to match its deficit) means that public debt has to keep rising. That is a sound outcome and will ensure that economic growth picks up and has a chance to eat into the huge pool of unemployment.

But to put all those realisations together you have to use a stock-flow consistent macroeconomic framework like MMT. The piecemeal (partial) analysis that goes for public debate does not come up with logically consistent outcomes because it ignores the interrelationships between the sectors.

Finally, the problem with the US Republican’s Balanced Budget amendment is that is will undermine economic activity. Even if the external sector was in balance each year, the sectoral balances then tell us that the private sector would be forced to have zero saving overall under an annual balanced budget rule.

If the private domestic sector tried to save overall, then such a rule would only be consistent with growth if the external sector created surpluses greater than the surpluses targetted by the private domestic sector. That coincidence hasn’t resembled any consistent period of recorded US history. It is highly unlikely to be consistent with the state of the non-government economy in the coming year.

A deeper understanding of the way the economy works requires us to understand what drives the income adjustments that are “accounted for” in the sectoral balances. An important starting point – often overlooked when fiscal rules are discussed – is the endogeneity of budget outcomes.

Fiscal austerity becomes self-defeating because private sector spending decisions overwhelm discretionary government policy changes. In Ireland, Greece, the UK and elsewhere budget deficits are rising and austerity grinds on.

The Balanced Budget amendment would destroy prosperity in the US. It would not allow the government to responsibly respond to negative fluctuations in private spending and the result would be the degradation of government services and entrenched unemployment.

It would be madness to introduce that into the US Constitution.

Conclusion

It is clear that the policy debate is being driven by advisers and material that presents a seriously deficient view of how the macroeconomy works.

A simple understanding of the sectoral balances provides a quick reality check to evaluate the statements coming from politicians.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – somewhat harder than last week!

That is enough for today!

“The problem is that once you comprehend the sectoral balances you will soon realise that this is logically impossible as a global solution. Not all countries can run external surpluses.”

Is it the case that Germany has managed to mask its weak domestic demand situation by exporting the problem to other countries? It looks to me like the German external sector is propping up the German economy in a manner that is more politically acceptable at the moment than using the government sector.

And the countries that have pegged themselves to the German currency then collapse under the strain as they export all their currency to Germany to fund their saving – unable to replenish it due to the peg. Insufficient money flowing (via austerity) then causes the real part of the economy to implode.

So the German export surplus appears to be as much of a problem as the Greek debt, but nobody is talking about it.

Apropos the latest US debt ceiling wrangling, I have a question for the experts in monetary operations. I suspect it is an easy question for most of you, but I don’t know the answer.

I want to preface my question by saying it is a question about what the US Federal Reserve System is legally permitted to do. It is not just a question about what an arbitrary sovereign government, abstractly considered, can do in some in-principle operational sense. It’s a legal question about a specific government and institution – the US government and the US Federal reserve system – and what they can do right now under existing US law.

Some background to the question: As I understand it, the US Treasury has accounts at the Fed, and these accounts are used to process federal government payments. If the government cuts a check to someone, that check is deposited in the recipient’s bank account. Ultimately, a Treasury department account is debited and the recipients account is credited. Similarly, if someone makes a tax payment to the federal government via check, the payer’s account will be debited and a Treasury account credited when the check clears.

So here’s the question:

Can the Fed, acting solely under legal authorities it already possesses, at its own discretion, simply credit a Treasury department account by some amount, without processing any payment into that account from another account?

Now it is my understanding that under current law the Fed cannot permit an overdraft on a Treasury account. But I’m not talking about an overdraft. As I understand it, an overdraft occurs in a bank account when the bank makes a payment from an account on insufficient funds. The full amount is debited from the account, and the account then has a negative balance. That negative balance is a liability of the account holder: they owe the bank money. They would usually have to pay a penalty.

But that’s not what I’m talking about. What I am asking is whether the Fed can effectively state something the following:

“We hereby create X dollars of fiat money, and credit those dollars to such-and-such Treasury Department account. End of story.”

I am also not talking about a Fed loan to the Treasury. Loans would be constrained by laws governing Treasury borrowing, and by laws prohibiting the Fed from purchasing Treasury debt directly, rather than on the open market. But again, I’m not talking about a loan. I’m just talking about the Fed creating money and giving it outright to the Treasury.

Can it do this? That is, is the Fed legally permitted to do this under current law?

“Can the Fed, acting solely under legal authorities it already possesses, at its own discretion, simply credit a Treasury department account by some amount, without processing any payment into that account from another account?”

No.

BTW, that was essentially the Mosler plan in the case of the ECB.

It looks to my untrained eye that this was the motivation for the rapid expansion of the eurozone, to use the periphery to depress the euro to the core’s benefit, locking in their advantage.

Thank you JKH. Can you point me to some location where I can find the relevant legal framework and restrictions laid out? I tried to get the answer from some of the Fed web pages, but couldn’t find it.

Sorry, I don’t have the detailed legal expertise, Dan. But I think it’s fundamental to the existing institutional configuration, with the clear separation of Treasury and the Fed, and the defined banking relationship to reflect that.

So I suppose its my opinion on the legality, without being able to reference it.

Some MMT’ers have researched the area more generally – I’ll be interested to see if they say something to the contrary. If I’m wrong, and they point to the legal proof, you have my apologies.

Bill,

An excellent, if a rather alarming message. Do you know of any politicians in the USA, UK or Australia who have an understanding at all of MMT and are prepared to give it public support or even talk about alternatives to the mainstream view of public sector deficits ? Keynes famously stated that ‘worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeeed unconventionally’ and it seems that politicians are more concerned with their reputations than actually advocating policies that will lead us back to full employment.

@Dan Kervick

I do not know if the Fed is legally allowed to provide an ‘overdraft’ to the Treasury. I would also be quite interested to know to what extent the Fed is considered part of the government since by law it is a private institution.

What the Fed can provide is a bond interest rate guarantee. It will stand ready to buy all available securities for a specific yield in the secondary market. That would more or less work as an overdraft to the Treasury since all participants in a bond auction would know that the Fed would provide them with funds a few minutes after they bought the bond (which they could later use for whatever purpose). The Fed would have to provide some mechanism to drain the excess reserves in order to maintain it’s target rate (probably some form of reserves savings account providing the target rate as interest).

Dan,

The prohibition probably falls out from rules covering the disbursement of funds by the Fed. The latter would include, broadly speaking, secured lending against acceptable collateral, and operating expenses such as salaries, etc.

The transaction you describe would be a credit to Treasury’s deposit account and a debit to Fed capital.

In the context of existing institutional arrangements, it is akin to “giving money away”. It’s effectively a principal fiscal transaction, outside of the bounds of the Fed’s normal spread banking function (which also has a fiscal effect).

Something would prohibit that.

And as you say, that’s different than a Treasury overdraft at the Fed, which if it were allowed, would be a credit to reserves and a debit to Treasury’s deposit account (making it negative). There’s no direct CB capital account impact from such an overdraft.

P.S.

It gets much cleaner if the Fed and Treasury are institutionally merged.

Then there’s no external Treasury account at the Fed.

Any such issue becomes internal to the combined entity, if its an issue at all.

It gets much cleaner if the Fed and Treasury are institutionally merged.

Yes, I think that institutional reform should be considered. However, I know a lot of folks about that idea of a national bank, and want the monetary authority to stay in some kind of quasi-independent entity.

Can the Fed, acting solely under legal authorities it already possesses, at its own discretion, simply credit a Treasury department account by some amount, without processing any payment into that account from another account?

I don’t know enough to answer this question, but I wonder why this question is important, as specifically worded. If the Treasury can tell the Fed to add dollars to the Treasury’s account, why should it matter whether or not the Fed can do so of its own accord? (I don’t even know if the Treasury can do that, mind you. I just don’t see why it should be necessary for whatever purpose for the Fed be able to effectively print money without the Treasury saying so. Am I missing something?)

WHQ,

I worded it the way I did because I took it for granted that the Treasury cannot tell the Fed to add dollars to Treasury’s accounts. The Fed is the monetary authority

Where I’m going with this is here: As a response o the current US government impasse, could Ben Bernanke, or the Fed governors, issue a statement to the following effect?

It is vital to the financial and monetary stability of the United States that the federal government be able to meet all of its financial obligations. This includes both obligations to pay its debts and obligations to disburse other funds through spending commitments that the US Congress has already explicitly authorized. Failure to meet obligations of either kind would diminish public confidence in the reliability of the federal government as a payer, and have serious and destabilizing financial ramifications. As the agency charged with guiding the monetary policy of the United States, and assuring the stability of the US financial system, the Federal Reserve is determined to make sure this kind of payment crisis never happens, and that federal government obligations are always above reproach.

All of the federal government’s payment obligations derive from previous Congressional authorizations for spending and borrowing. Typically, Congress authorizes a combination of sufficient revenue collection through taxation and borrowing to meet all payment commitments. However, if the US Congress is now refusing to allow the Treasury to accumulate sufficient funds in its accounts with the Fed to meet the payment obligations that the US Congress itself created, this is a serious matter of fiduciary failure by the Congress, a failure that calls for special action by the Fed. The Fed thus stands ready to use its monetary powers to assure that the US treasury always has sufficient dollars in its account for all of its mandated and Congressionally authorized payments to clear. No borrower who has been promised an interest payment, no construction firm that has been promised payment for authorized work done, no US soldier serving abroad who is owed a salary payment, ever has to worry about receiving payment from the federal government. Congress has the power to adequately fund the US treasury through taxation and borrowing. But if they do not provide sufficient funds for the Treasury’s accounts through those conventional means, the Fed will simply create the money that is needed and put it in those accounts.

Given the nature of the US political system and the procedure that must be followed to amend its constitution, I think it highly unlikely that a balanced budget amendment would ever pass. Moreover, Republicans are very fond of running budget deficits when they control the Whitehouse, so I don’t think they are even remotely serious about wanting such an amendment to their constitution.

The real point, as always, is simply to push the political debate into the extremes, and convince the American public that the budget must be balanced, and it must be balanced NOW. The reason for this position is to make sure that Obama not only has no political room in which to spend even a dime on anything that matters to his political constituency, but that he must cut spending that aids his constituency, thereby destroying his chances of re-election next year. Defeating Obama in 2012 is the only thing that matters to the Republican party, not the budget.

Walter, I agree and the implication is that a Republican victory in 2012 will bring stimulus – not the austerity that they are talking about now.

If that stimulus takes the form of tax cuts for the rich. The dark side wins yet again.

I can see that farce occurring.

@ Dan Kervick: Friday, June 24, 2011 at 20:53

Dan – can’t help with the legalese but operationally the scope is covered well here:

Modern Central Bank Operations – General Principles Scott Fullwiler 2008

Cheers …

jrbarch

“Not all countries can run external surpluses.

The striking aspect of the public debate is that an awareness of this logical inconsistency is low to zero (apart from MMT types).”

And not all countries can run external deficits.

Something that is also a striking aspect of the public debate as the awareness of this arithmetical inconsistency is low to zero.

If the arithmetical necessity of the sum of all current accounts equaling zero is coupled with the goal of no country becoming insolvent (no disastrous insolvency’s consequences as national assets imperilment or loss) then one deduces the necessity of:

– Countries alternating between current account surplus and current account deficits;

– No currency having a special or privileged status.

Or

– For any country the current account should average within short time scales to zero. “Short” meaning less than the scale necessary for insolvency to develop in any other country or in the country itself . (A)

Clearly, the current arrangements do not produce this outcome. Maybe a full fledged system of free floating fiat currencies corresponding to optimal currency areas does. Or maybe a Bancor type system is necessary. As it seems, the issue has not been investigated. Anyway…

Keynes may well be remembered in the future more for this insight (A) than any other.

Thanks JR Barch, and thanks others for the guidance.

Don’t mistake a “Balanced Budget Amendment” for an amendment that requires a balanced budget. They can be, almost assuredly will be, very different things. How hard would it be for the Federal government to take all of its capital spending off balance sheet? You set up a trust fund and you sell it Treasury bonds. Then it builds roads and stuff and leases them to the government for an amount roughly equal to the interest on the bonds plus the cost of maintenance. When there is a shortfall in the budget, the government capitalizes the interest under some magical accounting device that does not treat the capitalization as “spending” for purposes of the amendment. Rinse. Repeat.

With the right smoke and mirrors, balancing the budget should be a piece of cake.

While “lazy” Greek labor made them self “uncompetitive” on the global market Greek export in inflation adjusted dollars did grow 40% from 2002 to peak year 2008. And the Greeks had well more than twice of the German productivity growth (97-07) and wage increases below productivity growth. How can export grow 40% when the workers have made them self totally uncompetitive? Albeit German export did grow 51%.

The Greek export growth has the same pattern that many other countries; it takes off in a steep upward curve in the late 80′s and beginning of the 90s.

1987 – 2008 Export growth in inflation adjusted dollar:

Argentina 267%, Germany 284%, Greece 197%, Sweden 208%

A significantly change from the previous decades, including the post war record decades where domestic demand was the economic driving force. The growth is spiking upwards in a even way over the period, what is causing problem in current account in some countries is import and other factors in the current account.

This kind of crisis is always blamed on the working people being uncompetitive, to high wages, and an “overvalued” currency put the export sector in shambles the news say. It is peculiar how the export can continue to grow relatively steady, the dents in the curve is obvious in most part related to external things like global recessions. It seems like the “to high wages” and “overvalued” currencies have much more effect on import than export.

There has recently been some discussion that the government does not need to observe the debt limit and is constiutionally obligated to pay all debt. So the Fed could use the suggested wording.

“Can the Fed, acting solely under legal authorities it already possesses, at its own discretion, simply credit a Treasury department account by some amount, without processing any payment into that account from another account?”

The logical answer appears to be YES. Reason being that the money supply (and also the banking system’s stock of reserves and bonds) must increase in line with the needs of a growing economy, if one desires to have a happy and prosperous society. The increase in reserves required to support any productivity increase can only be accommodated by a net deficit. I cannot see any mechanism by which such an ongoing average deficit can be accommodated other than by having at least a small portion of central government spending unmatched by taxation receipts plus borrowing.

” The increase in reserves required to support any productivity increase can only be accommodated by a net deficit.”

Is this a reasonable place to ask why reserves necessary at all? If banks could create money against unrealized capital gains without bothering with reserves – so long as they have adequate capital and can borrow liquidity from some overnight facility or other – why would “vertical money” be necessary at all?

I see the accounting identities, but I cannot link them to the real world. One day, a company in which I own 10,000 of 1,000,000,000 shares is selling at $1 a share. The next day, the FDA approves its cure for everything, and I’m a millionaire, with a margin account and everything. How have private savings for purposes of money creation not increased by $100,000,000,000? When people take their profits, is that part of GDP? When they borrow against their new wealth – not only on margin but because owning wealth makes them creditworthy where once they might not have been – do they need Uncle Sam to have run a deficit other than to satisfy arbitrary reserve requirements and the equally arbitrary restrictions on what the central bank may buy?

The dotcom bubble didn’t HAVE to be a bubble. In theory, that value could have reflected future wealth. But where is borrowable future wealth in the accounting identities? Why is only booked wealth counted? The owners of capital assets take their future fruits into account in doing THEIR econonomics. Why can’t economists?

Creditiworthiness is a synergistic asset that emerges when a person or institution reverses enough entropy to make future wealth seem (to a potential creditor) likely to emerge from further efforts. A Picasso is creditworthy because he can scribble a pigeon and sell it. I am not, because my pigeons are not in such hot demand. Each sale of a Picasso pigeon for more than the last expands the creditworthiness of Picasso and everyone who owns a Picasso instantaneously. Why would the government have to spend a nickle for that increase in wealth to be monetized?

There is no substance left to the idea that the government collects taxes so that its money will be accepted. An economy runs best on a single currency, so we have agreed to use the one sanctioned by our representatives in Congress. Taxes may have been necessary to demonstrate to the people the advantages of a single, consensus currency, but once the point was made, the training wheels called “taxes” could come off, just as the requirement that the money be “backed” by metal could be removed. (Money was never backed by metal: it was always backed by what it could buy when its owner attempted to spend it; metal was just PROOF of scarcity, a function now served by a robust market and instant communications.)

Has anyone done the accounting identities in a way that includes asset appreciation as “income”? Do Prof Keen’s circuitist differential equations achieve that result? (They’re way beyond my meagre math skills.) But even it the economic effects of asset appreciation, especially appreciation based on future material outputs arising from entrepreneurially reversed entropy, that would just make the existing equations less descriptive; it would not make the economy any different from what it is.

Make that

” But even it the economic effects of asset appreciation, especially appreciation based on future material outputs arising from entrepreneurially reversed entropy, cannot be modeled, that would just make the existing equations less descriptive; it would not make the economy any different from what it is.

Sorry, I did not realize how the “preview thing worked”