I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

In policy you have to wish for the possible

I am travelling today and so have to steal time to write this blog between other commitments. Later this week I am presenting a paper at a workshop on stock-flow consistent macroeconomics and I was thinking over the weekend just gone what I would do with the time I have for the presentation (1 hour). I started putting together a database of IMF forecasts out to 2016 for various nations and simulating the implications for the sectoral balances. Then I thought I would discuss the internal inconsistencies of those forecasts from a stock-flow perspective and the implications of those inconsistencies. I will write a blog later in the week on that once I have finalised the presentation. But the preliminary thinking led to today’s blog. In policy you have to wish for the possible.

When the crisis began, the mainstream loathing of discretionary fiscal expansion was put on hold as pragmatic politicians realised the world economy was heading for depression. Their initial efforts in 2008 and 2009 staved that outcome off and a recession was the result – a very severe recession. The problem is that the conservative voices didn’t stay silent for long enough.

Soon enough, governments all around the World came under pressure from the conservative loathing of their efforts and fiscal austerity became the flavour of the times. The IMF was pushing that – they kept emphasising the need for “credible fiscal consolidation” plans despite being unable to explain what might happen if the governments kept expanding deficits and

All we heard was the usual cacophony of – higher interest rates, hyperinflation risks, drowning (under debt) grandchildren – and all the rest of the flawed doctrine that defines mainstream macroeconomics which helped create the crisis in the first place.

If only China had not continued to grow. Then the situation would have been more dire (especially in nations such as Australia) and perhaps the fiscal stimulus packages would have expanded further to cement a more durable economic recovery.

But fiscal austerity has emerged as the main game now.

The IMF has just come out (June 17, 2011) with their World Economic Outlook Update – where they finally acknowledge the obvious:

Activity is slowing down temporarily, and downside risks have increased again. The global expansion remains unbalanced. Growth in many advanced economies is still weak, considering the depth of the recession. In addition, the mild slowdown observed in the second quarter of 2011 is not reassuring.

Notice they cannot bring themselves to tell it as it is – using qualifiers like “temporarily” (yes: in relation to what?).

But in acknowledging that their previous growth forecasts (in the April 2011 World Economic Outlook) were too optimistic they cannot help reiterate the party line:

Fiscal challenges continue to pose various risks for the recovery. A first set of concerns revolves around fiscal imbalances in the euro area periphery. A second set involves the large near-term fiscal adjustment in the United Sates against a still-fragile recovery. A third set of concerns centers on medium-term fiscal sustainability in the United States and Japan. In the United States, these risks are rising because of the absence of credible consolidation and reform plans, while Japan’s plans must be made sufficiently ambitious and be implemented. In Japan, the fiscal response to the earthquake has raised challenges to attaining medium-term fiscal sustainability. Some credit rating agencies have already put U.S. and Japanese sovereign credit ratings on negative watch.

There is no economic content in that statement. It is a purely ideological statement that reinforces the irrational politics that is abroad at present in all nations and which is running counter to the will of the people (as evidenced by the growing social unrest in places like Greece).

First, the only risk that fiscal policy is posing for the recovery is that there is insufficient expansion in all nations. I include the Euro-area in that statement. Greece is only in trouble because it cannot grow. It cannot grow because the government is choking the life out of the economy by cutting its own spending and restricting the capacity of the private sector to fill the gap.

Second, what are the “medium-term fiscal sustainability” concerns for the US and Japan? The IMF has been going on about Japan for 20 years and still interest rates are around zero, inflation is around zero, there are queues lining up to buy its debt, and whenever the government maintains its fiscal nerve the economy grows relatively robustly.

There are no “fiscal sustainability” issues for nations that issue their own currency. There is inflation risk but there is never a question that the government cannot pay any of its bills that are denominated in its own currency. Please read the suite of blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 – for a different view of fiscal sustainability.

The only fiscal risk in the US and Japan is that imposed by increasingly dysfunctional political systems which threaten the capacity of the respective governments to ensure that aggregate demand is growing strongly enough and the next generation of adults are not wallowing in unemployment (and in the case of Japan – rising suicide rates).

Third, the earthquake has been a devastating experience for Japan but it has not altered the fiscal capacity of the Japanese government one iota. As long as there are real resources available for the Government to deploy then it can always afford to purchase them and use them to rebuild the damaged regions. Running a budget deficit today doesn’t change the capacity to run a budget deficit tomorrow. Running a budget surplus today does not provide a government with increased capacity to run a deficit tomorrow.

The IMF have always pushed the line that surpluses store up capacity so that a government can respond to a crisis should the need arise. That reasoning is totally false. The Japanese government has all the fiscal capacity it needs to respond the the natural disasters – irrespective of its debt ratio and other irrelevant ratios that the IMF and their ilk continually spout out.

The only thing that fiscal policy cannot address is the loss of life and the destroyed memories.

On a related theme, a lot of readers write to me asking my opinion on the alleged “corruption” and “tax evasion” in nations like Greece. That sort of stylisation is very popular in the mainstream press – that Greeks have been living beyond their means for year by paying themselves exotic public sector wages and having too many holidays. I cannot comment on that – there is a paucity of data available to confirm that conjecture and I do not consider the ravings of the German press to be a reliable witness.

But even if it was true you don’t get back to “living within your means” by driving unemployment towards twenty percent and youth unemployment much higher. I am sure the teenagers in Greece haven’t been “swanning around” and “getting fat” on bloated public sector wages.

The point is that when there is insufficient aggregate demand the government has to increase it or else face the consequences of slower economic growth and higher unemployment. Within that macroeconomics constraint the government may want to sort some “inefficiencies” out – like a “bloated public sector” and a “lazy tax base” should these problems exist.

That is one of the features of fiscal policy. It can simultaneously adjust the level and composition of aggregate demand with a mix of tax and spending measures. Monetary policy – adjusting interest rates – is unable to be finely tuned enough to not only boost aggregate demand but shift the composition of that demand.

What do I mean by shifting the composition of demand? I have noted that some commentators often want to talk about inequality and some even suggest that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) promotes a saving lust mentality in the private sector.

I write very little about redistribution policy because at present the main game appears to be debating about the level of demand. But I would have thought that throughout my writing (including my published academic work) that I emphasise inclusive societies where wages should grow in proportion to productivity and consumers be able to enjoy a reasonable material standard of living without recourse to ever increasing indebtedness. I will come back to that soon.

Within that ambit, fiscal policy can certainly redistribute income at the same time as expanding aggregate demand. I often attack what I call “corporate welfare”. I also note that if the introduction of, say, a Job Guarantee – which would see all workers who wanted a job but could not find one be able to work in a socially acceptable minimum wage public sector job – caused demand pressures then the government would have to increase taxes to create the “real” space for its policy agenda.

The tax increase would not be the result of the government having to “pay” for its employment creation policy (that is, to fund the spending). Rather it would be (if required) necessary to ensure that growth in aggregate demand maintained consistency with the growth in real productive capacity to ensure that inflation was benign.

That is the concept of “real” space and the role that taxes at the macroeconomic level play in creating it. Please read my blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory – for more discussion on this point.

Ricardians nowhere to be seen in Britain

The UK Guardian carried a story (June 20, 2011) – Electricals sector running out of options as consumers switch off – which provided more evidence that the fiscal austerity being imposed on the British economy by the conservative government is damaging private spending.

Remember the “fiscal contraction” expansionists who told us that the Ricardian agents were just waiting for the signal that their “future tax burdens” would be lower as a result of governments cutting back their net spending.

Mainstream economic theory claims that that private spending is weak because we are scared of the future tax implications of the rising budget deficits. Yes, there were meant to be all these households and firms poised waiting for the announcement of the austerity strategy – so that they could get back to spending again and the economy would grow without public spending support.

But, the overwhelming evidence shows that firms will not invest while consumption is weak and households will not spend because they scared of becoming unemployed and are trying to reduce their bloated debt levels.

The Guardian story is clear:

Comet is burning out, Best Buy has had the worst of starts in the UK and it may be Game over for the console specialist … The credit crunch has set in train a dramatic reckoning for the high street, with wilting demand testing traditional retail models to breaking point … UK consumer electronics sales have been hard hit as shoppers have cut back on discretionary purchases in the face of rising petrol prices and government austerity measures.

Remember that part of the inflation story in Britain is linked to the austerity measures (VAT hikes).

The latest retail sales data from the British Office for National Statistics said that:

Over the period April 2011 to May 2011 retail sales volumes decreased by 1.4 per cent and value also decreased by the same amount. Possible reasons for the decrease in May are consumers cutting back due to the economic climate, for example increasing fuel prices and uncertainty over job prospects and pay.

This is the fastest decline since the recession officially ended.

The Guardian reports a solvency expert who says that British “consumers are only behaving rationally, because its own research shows one in 10 people fear redundancy”. Entrenched unemployment and the increasing probability of job loss are very deflationary forces. They breed a lack of confidence that permeates into business investment and require public deficit intervention.

The Ricardian-proponents are once again wrong. The British government justified its austerity measures, in part, on a belief that the British households and firms were Ricardian in inclination. That is the way they claimed that growth would not be unduly damaged by what was clearly an act of vandalism on their behalf.

There is no consistent data both from the household and firm sector indicating that private spending is slowing

While berating the British government for their fiscal approach which has all but undermined the nascent recovery that was under way in that nation as a result of the fiscal support extended by the last government, it could be argued that the decline in consumer spending is a positive outcome.

I have sympathy for that view from a macroeconomic perspective.

The private domestic sector cannot continue to expand its spending out of a very flat real wage income and reduce its very high debt levels at the same time. Overall, private spending has to come return to more historical proportions of GDP. This will also have the impact of reducing the external deficit if import spending falls somewhat.

But what this means is that public net spending has to almost assuredly in most advanced nations be in continuous deficit. From a stock-flow consistent basis, there is no sense in the statement that the private and public sectors have to reduce their debt levels while the external sector remains in deficit.

That goal – which drives a lot of the fiscal austerity narrative – is impossible to achieve from a macroeconomic perspective without seriously damaging growth in the first instance along the way to finding out that a private de-leveraging exercise has to be supported by public deficits.

If the financial commentators and politicians understood that they might stop to think before they write and pretend to be experts on matters pertaining to the dynamics of the macroeconomy.

The financial crisis was a private debt issue. The solution is to attack the causes of the credit binge in the 1990s and beyond which largely means reversing the neo-liberal deregulation of the financial and labour markets and restoring government oversight of both.

The solution requires major reforms to the way banks operate and an outright banning of some financial market behaviour. Please read my blog – Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks – for more discussion on this point.

The solution also requires that real wages grow in line with productivity growth. That requires a major rethink of how we distribute income and has implications for tax policy and labour market regulation. Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

The fact is that there is too much consumption overall but not enough at the lower income levels and certainly not enough by the unemployed. That sort of imbalance is the major policy challenge and can be addressed via appropriate fiscal policy design. There is very little discussion along these lines though in the public debate.

That will be the topic of my presentation later this week. In assembling some cases though I started with the US which I briefly consider in the closing section today.

Sectoral balances in the US

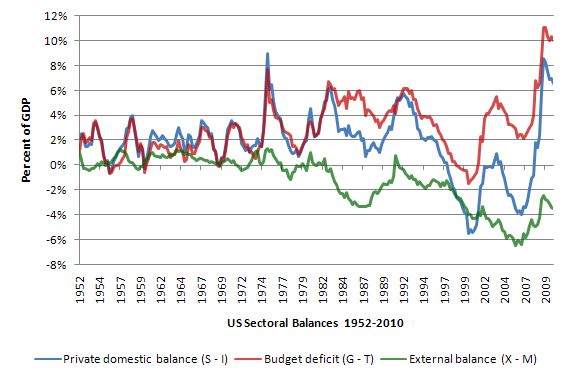

The following graph shows the sectoral balances for the US from March 1952 (that is, first quarter) to the third quarter 2010 (thanks to Scot Fullwiler for the data). It provides some historical context for the discussion to follow – in particular to disabuse readers of the notion that the recent behaviour of the private domestic sector is typical and to reinforce the notion that budget deficits are typical aspects of macroeconomics in the US (and of-course almost all advanced nations with external deficits).

The background to the graph is provided in this blog – Saturday Quiz – June 11, 2011 – answers and discussion. By way of summary, the National Accounts (which are assembled according to an internationally accepted and practiced methodology) can be interpreted as describing the interrelationships between the balances of spending and income for the three macroeconomic sectors (private domestic, government and external sector).

The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (S – I) is positive if in surplus and negative if in deficit. S is private saving while I is private investment. If the private domestic sector is spending more overall than they are earning then (S – I) is negative and vice versa.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) is positive if in deficit and negative if in surplus. G is total government spending and T is total tax revenue.

- The External (or Current Account) balance (X – M) is positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit. X is total exports and M is total imports.

We can write the accounting relationship between the three sector balances (that is, it must hold at all times) as:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

Or:

(S – I) – (G – T) – (X – M) = 0

If you do not understand the derivation of these balances then please refer back to the blog noted above for a more detailed explanation.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

But remember the sectoral balance rule is derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times. It is not a matter of opinion.

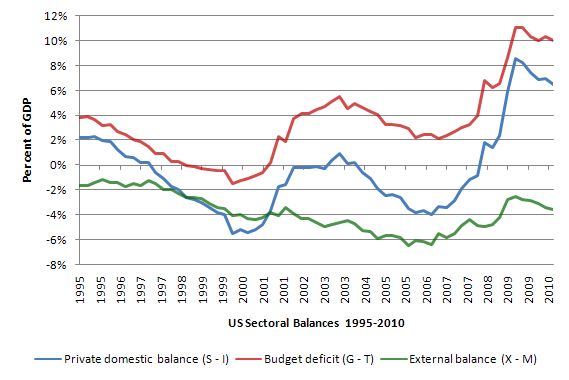

The next graph focuses on the period 1995 (first quarter) to 2010 (third quarter) and so embrace the Clinton period surpluses and beyond. It was during this period that the origins of the financial crisis starting to consolidate.

While the external sector deficit was fluctuating between 2 and 4 per cent of GDP in this period, the swings in private saving and the budget balance were much larger.

It is clear – as the accounting dictates – that the private and public balances will move closely together when the external balance is not fluctuating as much.

The causality is not clear and you have to understand the dynamics of each episode including the way the macroeconomy operates to infer which balance drives the other at any point in time. The statement that government surpluses (deficits) have to equal non-government deficits (surpluses) only takes us so far down the road to comprehension. Just as does the statement when there is an external deficit and the private domestic sector is overall spending less than they are earning, the government must be in deficit takes us only so far.

But from an MMT perspective, the balances are an essential starting point to understanding macroeconomic outcomes in addition, to providing a framework from which to check the consistency of statements relating to movements in stocks and flows – such as, the private and public sector can simultaneously reduce their debt levels (that is, run surpluses and pay down debt) when there is an external deficit.

I have chosen this period to look at because it shows what is going on at the moment (or in the third-quarter 2010) and serves as an useful point for conjecture. Moreover, several readers have asked me about the Clinton surpluses in the late 1990s which preceded the recession in 2001. How does MMT interpret those surpluses?

So we will deal with that question first. There are two broad ways of viewing the Clinton surpluses. (a) from a pragmatic perspective; and (b) from the perspective of sound, overall fiscal management.

First, from a pragmatic perspective – the external sector deficit was around 2.5 per cent of GDP and therefore draining aggregate demand (contracting growth). But at the same time, the private domestic sector was fully engaged in its credit-binge had started to drive growth strongly and unemployment was relatively low by historical standards.

In the third quarter 1997, private domestic overall saving went negative and that dis-saving for the sector grew substantially over the next few years reaching a peak of 5.47 per cent of GDP in the first quarter 2001 just before the recession.

So from a pragmatic perspective, the surpluses (of between 0.10 per cent of GDP in the fourth-quarter 1998 to the peak of 1.47 per cent of GDP in the first quarter 2001) we offsetting the significant aggregate demand boost coming from the private spending – all credit-driven.

The fact that this was unsustainable was self-evident and the recession that followed was a direct result of the credit-binge. The financial crisis that followed later in the decade and is still being experienced had its origins in this earlier period. The private sector did not restore the saving behaviour after the 2001 recession as we saw in the previous analysis.

Second, from a prudent fiscal management perspective, the US government (like other governments around the world) fell prey to the neo-liberal mantra about self-regulating financial markets and the need for more deregulation generally in the economy (including attacks on the welfare system). This was the period where the financial markets outgrew their usefulness (by a large margin) and introduced the aggressive financial engineering into the picture which led to the explosion in private debt.

Increasingly, with real wages flat or falling, private consumption could only be maintained through debt. The saturation point of “safe risk” was reached early on in this period but that was well below the satiation point for the financial engineers. They sought to broaden the scope of who would borrow and increasingly the lending margin pushed out into the unsustainable – people who even in times of strong employment would struggle to repay the debts especially given the ways the loans were structured (palatable at first, pernicious after a while) were borrowing way beyond any reasonable capacity.

Clinton oversaw the beginnings of the credit binge and should have stopped it and should never have given it oxygen. Unfortunately his advisers several of which still influence the current US government were in the neo-liberal camp and couldn’t see beyond the “Great Moderation” myth and the optimality of self-regulating private markets.

So from that perspective, Clinton is culpable in overseeing a growth strategy whereby consumption was maintained not by real wages growth but by credit – and allowing credit to be provided beyond the sustainable margin. If his administration had have been managing the economy in an appropriate manner then the fiscal surpluses (and concomitant fiscal drag) would never have been possible. It is in that context that I say that the Clinton surpluses set the US economy up for the 2001 recession.

The private domestic sector were squeezed by the surpluses at the same time as they were taking on increasing levels of debt. The two pressures eventually led to the 2001 recession. At that time, the rising budget deficits allowed the private domestic sector to resume saving but the problem was that the underlying cause was not addressed and under the Bush Administration there were no brakes put on the financial engineers and the financial crisis of 2007 and beyond was the manifestation of that policy laxity.

As the graph shows, the private sector has now firmly gone into saving mode as the combination of entrenched joblessness, threat of job loss and the overhang of huge private debt levels demand caution. This spending withdrawal by the private sector has reduced the external deficit (as import growth declines) and forced the budget into increasing deficit. If the US government had have resisted that dynamic and tried to maintain a lower deficit by countering the automatic stabiliser component (falling cyclical tax revenue and increased welfare outlays) with discretionary spending restraint then the US unemployment rate would have been much higher than it already is.

The current agenda which is being followed by both main parties will not bring the deficit down as a percentage of GDP while the private domestic sector is intent on reducing its debt exposure. The current policy agenda will reduce economic growth and pit the automatic stabilisers (pushing a rising deficit) against the discretionary cuts. What most commentators do not recognise or admit if they do is that the private spending (and saving) decisions are very powerful and the government cannot really run counter to them.

The appropriate role of government is not to try to force a lower deficit when there is such entrenched unemployment and no demand-pull inflation. The correct policy response in this environment is to accommodate the private spending plans to ensure that there is sufficient aggregate demand to propel growth. That suggests in the current situation that the budget deficit has to rise.

If I am asked whether the budget deficit is “too large” the first question I ask is – What is the unemployment rate? In usual circumstances, when there is mass unemployment you know at least one other thing – the budget deficit is too small.

The private sector has to reduce debt which in the current climate (external deficits) and institutional arrangements (government issues debt to match its deficit) means that public debt has to keep rising. That is a sound outcome and will ensure that economic growth picks up and has a chance to eat into the huge pool of unemployment.

Conclusion

I have to rush now as I have a plane to catch. More tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

One technicality:

The sectoral balances have to be plotted with current account balance instead of the trade balance. The most accurate three balances equation is with the former.

This is especially true for Australia which has been running a trade surplus recently but a negative current account balance like before. The trade balance in Mar Qtr 2011 was plus A$3,030m and the current account balance minus A$10,447m.

I asked some questions about taxes the other day so let me try a different angle today:

If we were to ask the heads of (and senior officials of) the Australian taxation office, or the internal revenue service, or inland revenue and so on, whether or not the collection of taxes was necessary in order to fund government what do we suppose the answer would be?

Ditto senior treasury officials.

My bet would be a unanimous assertion that taxes fund government. What do others think and does anyone have any quotes from senior tax and treasury officials one way or the other?

thanks

Mike,

Well of course they would. If you asked a Church of England Bishop if there is a God you would similarly get a positive answer.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his job depends on not understanding it.” – Upton Sinclair

Ramanan is right of course but that is one area I haven’t really grasped. Isn’t the CAD & Trade Balance more or less the same thing? I guess what I’m asking is What is the difference? How do they differ?

But even if it was true you don’t get back to “living within your means” by driving unemployment towards twenty percent and youth unemployment much higher.

Why isn’t this more obvious to policy-makers? To live within one’s means is to live on the basis of income drawn from one’s work as opposed to income derived from credit. If you want people to increase the degree to which they live within their means without at the same time collapsing the economy, you need to expand employment.

I understand that taxes don’t fund soverign government spending and that a jobs guarentee would put people to work, but would a government not have to have a progressive tax structure for MMT to work? I ask because it seems to me if there is simply a budget deficit then a lot of the money may go to the rich who will simply invest it in different markets, a lot of it being used for speculation. What is MMT”s stance on the progressive tax structure?

Senexx,

There are other income flows between residents and foreigners such as interest payments on securities etc. So such things are included in the CA.

So if a foreigner holds Australian Government bonds, the interest payment has to be included in the CA.

There is a blog entry here at Billy Blog (can’t find) on this especially specific to Australian terminology- you should be able to find it out.

Thanks Ramanan, I’ll find it.

I thought that may have been the difference. So I presume the Trade Balance is just that – Trade only.

Senexx,

This recent post by Bill goes into some of these issues towards the end I believe:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=14919#more-14919

And here is a recent US BEA report that breaks down the Current Account (Table F.2) into it’s component parts:

http://www.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2011/05%20May/D%20pages/0511dpg_f.pdf

Resp,

Mike: “My bet would be a unanimous assertion that taxes fund government. What do others think and does anyone have any quotes from senior tax and treasury officials one way or the other?”

Confirmation bias.

Senexx,

Here: https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=12577

Hi Ramanan,

Regarding current account vs. trade balance, you’re 100% right. The data Bill is presenting is the current account. For simplicity, we usually use (following Wynne Godley’s lead in the mid-to-late 1990s) the basic macro national income accounting equation when describing the sector balances, though (again, as you note) it’s not actually the same thing.

Scott, why is the basic national income equation stated using (X-M) when using the CAD is correct? Seems very strange. Anything else left out in the equation?

“I was thinking over the weekend just gone what I would do with the time I have for the presentation (1 hour).”

“In policy you have to wish for the possible.”

How about the difference(s) between creating more medium of exchange with currency/demand deposits with no loan/bond attached and attempting to create more medium of exchange from demand deposits with a loan/bond attached (debt), specifically the time differences between spending and earning that debt allow and if debt can be used to keep a currency from depreciating?

And, “The financial crisis was a private debt issue.”

IMO, add in gov’t debt too. It is a too much debt crisis.

Good luck with that. Almost all economists believe that as long as there is no price inflation, there is no such thing a s too much debt.

I believe your sectoral balance approach assumes the currency printing entity is not allowed to create more medium of exchange with no bond/loan attached.

One question I would have:

If you look at the BEA’s pdf Table F.2 in the link in my comment above, it looks like the Current Account just does consist of Exports and Imports (for goods and services) plus “Income Receipts” and “Income Payments”.

Now if you look at Line 13 in the Table F.2, under Income Receipts, it lists something called “Income Receipts on US owned assets abroad”… and the number reported is in USD, but can these “assets abroad” earn actual USDs? Or is this the USD equivalent at some exchange rate? How could an “asset abroad” yield actual USDs?

Resp,

@Ramanan

Thank you for the Blog link RE:Current Account

So now the identity makes more sense to me

C+S+T-NPI=C+I+G+X-M+NSI

I think that is the correct balance, no?

does NPI+NSI=0 like

CA+KA=0

where CA=Current Account

KA=Capital Account

Or am I still missing something here?

“And, “The financial crisis was a private debt issue.””

You’ll need to refute things like this:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2008/12/hair-of-the-dog.html

“The same argument applies to low interest rates as a cure. If excessive gross debt is the underlying cause of the problem, there is no reason to think that low interest rates, by curing one symptom of the problem (insufficient spending), will make the underlying cause worse. Low interest rates encourage borrowers to borrow more; they also encourage lenders to lend less. It is not at all obvious that low interest rates will cause gross debt to increase further.

Again, there may be indirect effects on gross debt, via differences in marginal propensities to spend, or reducing the rate of default. But these side-effects on gross debt are just that: side effects of the cure, and not part of the way the cure works. Low interest rates cure a recession both by increasing the demand for loans and by reducing the supply of loans; they encourage an increase in spending through both channels, and can be effective even if gross debt stays exactly the same.

Low interest rates are Aspirin, not hair of the dog.”

That should not be too hard to refute.

[1] Regarding “redistribution” of wealth, it’s my view that this idea has no play under MMT and a sovereign fiat currency. Redistribution only exists when I tax one party’s wealth to give it to another, and in the MMT view, I am never doing that. While it is true that I am taxing one party, it is never to give that money to another party; merely to keep inflation at bay. And while it might also be true that I am also giving money to a second party, I am not getting that money from the party I am taxing, and therefore, I am not redistributing any money to that second party from the taxed party. True, this might look like splitting hairs to some, but I don’t believe it to be a small point. After all, the key gripe with government that seems to motivate the conservative mind is that their money is being “redistributed” to a lesser deserving party, and if there is no actual redistribution ocurring, this concern becomes unfounded.

[2] How do the Ricardians explain why consumers turn OFF spending in the present based on future expectations, but don’t seem to tun ON spending in the present when those future expectations are reversed? Is their “consumer” simply some little Hobbesian machine, always expecting the earth to fall out from under them? Why would this consumer ever do anything but save?

[3] Regarding the Clinton surpluses, the short paper, “Can Goldilocks Survive?”, published by Randy Wray (and Wynne Godley) in 1999, deals directly with the these surpluses AS THEY WERE OCCURRING. The openning bullet includes the words “an increasingly unsustainable debt burden,” the ONLY proper usage of the word “unsustainable” I’ve ever seen around discussions of macro. Needless to say, Randy’s prognosis then for Goldilocks was not good.

Here’s a link to a BEA document that provides some guidance on how the US ITAs (Current/Capital/Financial) are reported/accounted for:

http://www.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2010/02%20February/0210_guide.pdf

Resp,