I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

When ideological blinkers lead to denial

Let’s start with some facts: Fact 1: When private spending falls, economic growth will falter unless an increase in net public spending fills the gap. Fact 2: Even if a government chose not to fill the gap, and instead did nothing, its budget deficit would rise as economic activity fell due to the operation of the automatic stabilisers (tax revenue falling, welfare spending rising). Fact 3: After a period of rising public deficits, if private spending remains flat, cutting the budget deficit will damage economic growth. Fact 4: When there is an external deficit (net exports negative), if a government runs a surplus, the private domestic sector must be running a deficit and accumulating indebtedness overall. If the private domestic sector resists that dynamic, then growth will falter and unemployment will rise. Fact 5: The central bank sets the interest rate. Within this context, with growth slowing, the private sector saving ratio rising, the external sector draining growth and labour underutilisation rates around 12 per cent, the last thing the Federal government should be doing is cutting net spending in next week’s Federal Budget. But it is the very thing they are proposing to do. They have been captured by the deficit terrorists and cannot see beyond the “surplus is good” mantra. At the moment, the pursuit of austerity will be very destructive. News Limited journalists have become obsessed with the deficit and continually demand higher surpluses. They also seem to be oblivious to the on-going developments in the economy. This article, May 3, 2011 – Deficit is driving up the Australian dollar – from The Australian newspaper’s economics editor, Michael Stutchbury is no exception. Stutchbury regularly writes the same column twisting it a bit here and there but the message is always the same – the budget deficit needs to be a budget surplus. In this article (rant) , he writes:

…. the more fundamental story is that Canberra’s structural budget weakness is helping to drive the Australian currency to its new post-float high of $US1.10. The deficit blow-out to be revealed a week from tonight will mean that the budget’s bottom line is perhaps two to three percentage points of gross domestic product – or perhaps $40 billion – structurally looser than demanded by the mining boom, our record high export prices and a jobless rate heading below its “natural” 5 per cent level. Instead of being close to $50bn in the red, the budget already should be building up a solid surplus buffer to stabilise the mining boom economy.At least this is a twist on the usual argument presented by opponents of deficits that in open economies they lead to a collapse in the currency. I suppose anything will do when you are obsessed. I will come back to some of the other components of this quote later but what are the mechanisms that Stutchbury thinks relate the budget deficit to the appreciating $AUD. He mounts the case that “the floating dollar and the budget bottom line need to fully play their role as the economy’s front-line “automatic stabilisers”” and by which he means that when private spending growth is strong and the economy approaches capacity, public spending growth should moderate. At the same time, if the growth is sourced by an export boom then the exchange rate will also appreciate to ease inflationary pressures and stifle some of that “externally sourced” growth. I agree with all of that except then you have to examine the facts. If growth is insufficient to fully employ all available resources … AND …if the external sector is not adding to growth … AND … if private spending is still dragging …. then you do not move the budget position towards surplus much less into surplus. The facts sheet about the Australian economy does not include a statement that the external sector is a net contributor to economic growth in Australia at present. The most recent National Accounts showed that the external sector was still a drain on economic growth. Please read my blog – Australian National Accounts – I wouldn’t say the economy is great – for more discussion on this point. Stutchbury can go on about how strong the economy is but a boom in one sector that doesn’t feed through to the rest of the economy is not a signal that the budget deficit should be cut. Further, unless the external sector boom overall (that is, its contribution to growth) is sufficient to fully accommodate any desire to net save by the private domestic sector then the public balance has to stay in deficit for growth to continue. Australia’s external performance is not anywhere near that level at present. Stutchbury also continues to run the line that the Government:

… splurged too much again during the financial crisis with its excess budget stimulus.Well that should have resulted in strong growth being maintained and no rise in unemployment and underemployment. The reality is the opposite. Growth slumped and remains subdued and labour underutilisation rates rose by nearly 50 per cent (combined unemployment and underemployment). The reality is that the fiscal stimulus was inadequate and has been withdrawn too early. He also mounts a very curious “insurance-type” proposal which is contrary to sound fiscal management. Apparently, he thinks the budget position now should constrain growth so that the exchange rate will not rise as far. He claims that this would make the demand shock arising from the “unravelling of the global commodity price bubble” less “messy” – because we would already be stifling growth as a result of the fiscal drag. But a government’s role is not to undermine economic growth “just in case” the growth becomes too strong and pushes the economy up against the inflation barrier. At present core inflation is low and the Reserve Bank maintained its target rate (yesterday) for the 6th month in a row. With idle labour and signs that the economy is contracting – now is not the time for the Government to be stifling growth even further. Is there evidence for my position? We received two pieces of economic data that also confirms my position that economic growth is faltering. First, the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the Retail Sales data for March 2011 today and the results apparently “surprised” economists – all except this one! The main highlights of the March 2011 data were:

- Seasonally adjusted retail sales fell 0.5 per cent in March 2011.

- In volume terms (that is, adjusting for inflation), the trend estimate for retail turnover fell 0.1 per cent in the March quarter 2011.

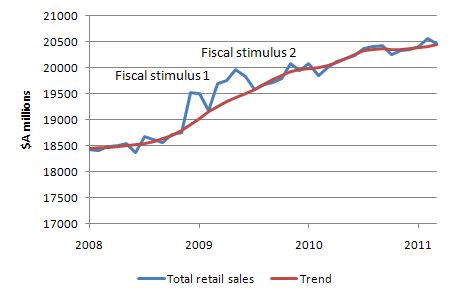

Retail sales unexpectedly fell in March, the first drop in five months, offering further evidence of a cautious consumer that argues against the need for a near-term hike in interest rates … the Bureau of Statistics reported sales fell 0.5 per cent in March, confounding forecasts of a 0.5 per cent increase. Real sales for the whole quarter were disappointingly flat as well, adding to the risk that the economy contracted in the quarter.The forecasts were confounded because they are guesses from (mostly) bank economists who are caught up in the “once-in-a-hundred-year” mining boom narrative that the Government and journalists have been running for some time now as part of the cover they need to hack into net public spending as they mindlessly pursue their budget surplus ambitions. The following growth shows the seasonally adjusted and volume measures (in nominal terms). The two bumps relate to the two fiscal stimulus packages (December 2008 and February 2009) which the Federal government introduced as the financial crisis unfolded.

The reality is that household spending is more subdued now after a decade or more of credit-fuelled binging. As the Sydney Morning Herald article notes:

The reality is that household spending is more subdued now after a decade or more of credit-fuelled binging. As the Sydney Morning Herald article notes:

Australians have turned more frugal since the global financial crisis shocked them into saving more. The household savings ratio has climbed back to nearly 10 per cent having been negative as recently as 2005.The credit binge was the major reason the Federal government was able to run surpluses between 1996 and 2007 (with one year of deficit). That was clearly an unsustainable growth strategy and now that households are saving again and running down debt, growth has to be supported by a return to on-going deficits. The period of surpluses was abnormal in our economic history. Stutchbury makes out that governments normally balanced the budget over the cycle but that is historically inaccurate. The federal budget was typically in deficit. The other major data release today from the ABS was – Dwelling Approvals – which gives a guide to how construction is faring. The take-home result is that Total dwelling units approved fell by 18.1 per cent over the last 12 months (although there was some improvement in March 2011). The trend was down 14.5 per cent over the year to March 2011 and falling. The ABS News coverage noted that the March 2011 result “was skewed upwards by a surge in the volatile apartments sector”. The “more stable and widely-watched private house approval figures eased 0.8 per cent”. So retail sales and construction are heading south! At least some private sector economists – who are typically gung-ho about the need for budget surpluses (except when specific assistance to their industry etc is threatened) – are starting to note the disconnect between the “surplus at all costs now” narrative and the reality. In this article (May 5, 2011) – Budget surplus a bridge too far – a leading bank economist notes that:

THE federal government has painted itself into a corner by committing to promising a budget surplus by 2012-13. That’s a major task. I don’t think we need to cut the deficit so quickly. Indeed, doing so could cost us dearly. It’s not just about fiscal responsibility. The logic is that growth driven by mining expenditure will soon lead to capacity and labour constraints. The government doesn’t want to crowd out the private sector and is making room for the minerals boom. Minerals prices are booming and the dollar keeps rising, but minerals projects are not coming through as quickly or as strongly as expected. Meanwhile, the rest of the economy isn’t all that strong. Outside the resources sector, weak profits are affecting tax revenues and business investment remains subdued. Housing is weak and households remain cautious. Growth is around 2.5 per cent — solid but not spectacular. The danger is that private expenditure won’t come through quickly enough to offset the stimulus from government spending. I think the government should keep spending on infrastructure until private investment comes through, but its focus appears to be on fiscal responsibility.I imagine if I sat down with this person and discussed macroeconomics we would not agree much. But I agree with all of this. The data today categorically shows that the economy is not booming – and is – possibly even contracting overall despite the “boom” (which is rather tepid at the moment) in the mining sector. The article then strays – apparently there has been a dramatic “blowout in the budget deficit because of fiscal stimulus after the global financial crisis”. What is a blowout? What do you assess the budget position against? There is no meaning in the descriptor “blowout” for a budget outcome. The budget is what it is. As noted above, the fact that unemployment and underemployment have risen by around 50 per cent since the crisis began tells me that the budget deficit didn’t rise enough to combat the slowdown in private spending. But it gets back on track when it notes that government should not cut infrastructure spending. The article says:

The last time the budget went into significant deficit, in the early 1990s recession, the result was 15 years of underinvestment in infrastructure. That’s why we ran into infrastructure bottlenecks in the middle of the last decade … Already, the GFC-induced fall in business investment means we’ll run into capacity constraints in some sectors in two to three years. Surely we can learn from the past and not compound that with underinvestment in government-funded infrastructure.The article argues strongly against trying to push for a budget surplus by 2012-13. The writer notes that the Government would “need to be really tough on expenditure” to define a trajectory towards surplus. The problem then is that they will undermine short-term growth and continue to starve public infrastructure spending which helps underwrite growth over the next few decades. In parting, we read:

Just remind me why, apart from politics and ideology, we have to reduce the deficit so quickly.The disagreement I would have with this economist is that he still maintains that fiscal responsibility requires the deficit be cut. His quibble, legitimate though it is, is limited to the speed of adjustment and the motivation at present for the government’s blind pursuit of surplus. The more general point that gets lost in all this debate is that deficits are not good nor are they evil. They primarily are not a suitable target for policy because they rise and fall on private spending fluctuations. It is far better to target employment maximisation and let the budget balance be whatever is required. But the Government is not thinking like this because it has got itself into a political straitjacket (of its own making) which “requires” it to push for a surplus. As each week’s economic data gets worse and the estimates of tax revenue fall even further, the Government just talks tougher about the need for even greater spending cuts. To say it is moronic is to understate how badly the neo-liberal ideology has infested the policy debate. The fact that growth is slowing should tell the Government all there is to know about the direction of fiscal policy in Australia at present. Conclusion Next Tuesday, the Federal Treasurer will bring down the Budget for 2011-12. The talk will be tough and the policies will further damage the economy. I think it will be another nail in the coffin of this government because they will not be able to claim they have overseen a strong economy with balanced growth (across sectors and regions). Unfortunately, for us, the Opposition is worse. We now differentiate our major political parties by shades of neo-liberalism. That is enough for today.]]>

Yes,damned if we do and damned if we don’t.Who the hell do we vote for in this situation which is straight out of Bedlam?

It’s not entirely true to say the labor hierarchy is infested with neo-liberal idealists. The policy is driven in large part by political pragmatism.

Liberals and the right wing the world over have a primary mode of attack. The left wing wonks are wasting public money and the right wing, business knowledgeable conservatives need to take over and fix the books. They also like to repeat the party line ad nauseum. Say it often enough and everyone believes it. Labor have in part been pushed into this policy by persistent right wing attacks.

Not apologizing for Labor. They are turncoats, incompetent or gutless whichever way you look at it.

Strikes me that one reason MMTers aren’t getting their message into the heads of deficit terrorists is that MMTers won’t concede that the terrorists have a point or two. For example what lies behind terrorists’ fear of deficits is their concern about ever rising national debts. And that is fair enough: debts cannot rise (relative to GDP) for ever, else a country ends up paying ludicrous amounts by way of interest.

The solution to the latter problem is to let deficits accumulate as extra monetary base rather than debt. To which the deficit Neanderthals / terrorists will respond that “money printing causes inflation”. MMTers then need to reply by pointing out that the purpose of money creation is to raise demand, and that inflation will not ensue unless that demand gets excessive.

Also funding deficits via debt is pretty stupid anyway. The purpose of a deficit is to bring stimulus. In contrast borrowing is anti-stimulatory, i.e. deflationary (in the demand reducing sense of the word). Funding a deficit with debt makes as much sense as pouring water in your car’s fuel tank.

P.S. I should have made a distinction above between the part of a deficit that is structural and the part incurred for stimulus purposes. Funding a structural deficit with debt is O.K. as long as the debt doesn’t grow too large. In contrast, funding a “stimulus” deficit with debt is stupid.

what the hell is a neo-liberal?? how is that different from little Johnny Howard?

A french colleague at work made the remark that a government should only be allowed to run a surplus if they had achieved their mandate of full employment. I suppose another issue is that Swan and co. believe that they have achieved this. They then went on to say that when they can have a surplus they should reduce taxes instead of “saving”.

What’s a neo liberal?

Basically it’s a right of center authoritarian. Bush, Thatcher, Blair, Howard, Rudd etc

Do the test at: http://www.politicalcompass.org/index

Full employment to them is the point at which employees start to get a modicum of negotiating power and there is a faint whiff of inflation in the air. God forbid any uppity workers eating into their company profits.

Ralph:

Letting spending accumulate as excess bank reserves for the banking system and deposits for the public at very low (zero?) interest rates accomplishes what you say if the interest rate on reserves is zero. If it’s higher than zero why not just pay low rates on short term bonds (and long term bonds for that matter) and get the quantity theory of money crowd off your back? In any event MMT is not dependent on a zero interest rate, it’s a policy choice. If you just set the (real) interest rates low enough on government bonds the debt/gdp ratio declines even with high spending. You accomplish the same thing you want but it looks more like standard procedure and gives your political opponents much less of a target. Moreover it leaves an avenue for people to earn some interest on deposits that is outside the control of the banking system. (Btw this is Scott Fullwiler’s position and personally I prefer it to Bill’s and Warren’s zero interest rate view)

Fact 4: When there is an external deficit (net exports negative), if a government runs a surplus, the private domestic sector must be running a deficit and accumulating indebtedness overall. If the private domestic sector resists that dynamic, then growth will falter and unemployment will rise.

Of all the messages that we need to get across, this is the one that has the greatest potential to make people say, “Oh, now I get it!”

“If it’s higher than zero why not just pay low rates on short term bonds (and long term bonds for that matter) and get the quantity theory of money crowd off your back?”

The other option is to supply bonds to those who require the government welfare – ie vesting private retirement pension. You could even extend this to providing a full government annuity in return for the pot (ie getting the insurance company middleman out of the equation). That has the advantage of destroying large amounts of financial assets now in return for a future income stream – and therefore would actually reduce the national debt.

Keith, That’s given me food for thought. A weakness in your suggestion is that it doesn’t entirely “get the quantity theory of money crowd off your back”. Reason is that your suggestion is similar to QE. That is, some of those being offered low interest govt debt in exchange for debt which reaches maturity will just keep their cash. So the monetary base DOES rise. Plus (as is the case with QE) they’ll seek better returns elsewhere – stock market, less developed countries, etc. And that is not a brilliant outcome.

What I like about the Bill / Warren view is that ties up with (or can potentially be made to tie up with) the distinction between the structural and stimulus deficit. That is, as far as a structural deficit goes, those with cash to spare must be persuaded (via an attractive rate of interest) to surrender their cash, so that they don’t spend it.

A stimulus deficit is quite different. I see no point whatever in borrowing or offering any interest to anyone. Just print cash and spend it, as per the Abba Lerner money pump (or if inflation looms, do the opposite: rein in money and “unprint” it.)

Once the above distinction is programmed into the brains of finance ministers, central bankers, etc. they then would not indulge in the absurdity of borrowing for stimulus purposes. That just results, to a greater or lesser degree, in crowding out. And there is no agreement amongst economists as to how serious a problem crowding out is. Tim Congdon even argued in the Financial Times yesterday that crowding out MORE than negates the stimulatory effects of Keynsian “borrow and spend”, i.e. that the effect of a stimulatory fiscal policy is the opposite of the intended effect! He ended by saying “Fiscalist Keynsianism, like history is bunk”. I agree.

Congdon’s letter is here: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/585fb09a-75dc-11e0-82c6-00144feabdc0.html

Hope the above makes some sort of sense. Feel free to award me marks out of ten!

Ralph @ 5:15:

With respect to your first paragraph, I agree you won’t get the quantity theory people entirely off your back but at least it would be a help. It surprises me how many non-economists I speak to have absorbed the quantity theory. It’s simple and intuitively appealing. So hewing to standard procedure would reassure them. Perhaps I’m wrong and it would make no difference but in my experience referring to something currently in effect that functions OK is more reassuring than proposing something different, even jarring, which I believe the no-bonds proposal is. Better to just go with bonds at some level of interest and keep it low (below the growth rate).

Your fourth paragraph: your crowding out sounds like quantity theory unless you’re assuming the economy is at full employment. Government spending creates the assets that are withdrawn through bond sales.

Neil Wilson @ 2:38:

A compromise position would indeed be to provide interest paying federal government securities to pension plans and individuals and let the rest accumulate as excess reserves at zero (?) interest. The banks would hate that though. They’d be stuck carrying zero interest assets (the excess reserves) which would presumably lower their profits a little. They’d then seek to pay their workers less, increase the margins on loans, increase cost of services, etc. Not sure how you’d control the market for those bonds either. If the individual or pension fund wanted to sell you’d have to control who was allowed to buy. Sounds like excessive micro-managing to me.

Ralph Musgrave says:

Neoliberals have many valid points, but that’s not one of them, as the interest revenue from their Central Bank cancels it out at least partially (and if they borrow directly from their Central Bank, it cancels it out fully).

Unless they can prove that, pointing it out will be a waste of time.

Anyway, circumstantial evidence suggests you are wrong: despite inflation targetting being inefficient, it does work even when demand is not excessive.

Firstly bringing stimulus is not always the purpose of a deficit. Secondly Bill has previously shown that borrowing is not necessarily antistimulatory. Thirdly the borrowing is on a longer timescale than the spending, so if it does have an antistimulatory effect then it doesn’t counteract the short term stimulatory effect.

But the main advantage of borrowing is that it allows the opportunity cost to be taken into account. If the government borrows more than interest rates would have to be higher for the same inflationary impact. Conversely, if the government borrows less then interest rates would have to be lower for the same inflationary impact, and that’s why the rush back to surplus in Australia isn’t as silly as Bill keeps claiming it is.

According to MMT, sovereign governments do not borrow! They are currency issuers, and spend by crediting bank accounts. Because they do not borrow, it logically follows that they have no debt either.

But they sure perform operations that closely resemble borrowing. They issue these saving instruments, government bonds, whose purpose is not to fund anything but to offer non-government sector some safe place to invest their money.

It used to be that these bonds were used to conduct monetary policy, i.e. FED set the overnight interest rate with them. Nowadays FED sets the target rate directly by paying interest on reserves.

And this whole process, government creating money trough deficit spending, resembles borrowing because it used to be, under gold standard, that the government had to borrow in order to finance itself. All ties to gold were severed when bretton woods system collapsed in 1971, but bond issuance, and some other legislative restrictions are relics from that era.

There are some tax regimes that don’t get much playtime that would improve the situation. Wealth taxes very rarely get accepted because they are blocked by the rich and powerful.

LVT will address the accumulation of land wealth at the center of power. I believe the Swiss operate a 1or 2% tax on asset wealth. Capital tax could be made more progressive (it’s now mostly a flat tax). Corporate taxes could also be made progressive.

Regressive tax like VAT can be made more progressive by issuing a citizen VAT premium.

The odd thing to my mind is the bourgeois get very hot under the collar when wealth tax is mentioned. Even though the middle class would mostly benefit, billionaires losing out. The ones who complain the most about dole scroungers, actually quite like the idea of sitting on their arses doing nothing but collecting rent. Ideally, enslaving dole scroungers and putting them to work.

I’ve just noticed the typo in my earlier posting. It should of course say If the government borrows more then interest rates would have to be higher for the same inflationary impact.

PZ says:

No, according to MMT they do not need to borrow. The difference is significant.

Andrew says:

Saturday, May 7, 2011 at 9:23

LVT should not be regarded as a wealth tax. Wealth taxes are a bad idea because their main effect is keeping rich people away. But the amount of land available is fixed, so buying it pushes up the price everyone else pays for it, therefore taxing it is only fair.

I’m not sure what you mean by capital tax – do you mean capital gains tax? If so, why do you think it should be made more progressive?

Aiden “Wealth taxes are a bad idea because their main effect is keeping rich people away. But the amount of land available is fixed, so buying it pushes up the price everyone else pays for it, therefore taxing it is only fair.”

-A wealth tax (or asset tax or whatever you call it) could be levied on all citizens of a country irrespective of where they lived and on all of their assets irrespective of where they were held. That might make some rich people change citizenship. My guess is that a country has more need of people who are high earners rather than those with great wealth (supposing that rich people are so important). Having a wealth tax instead of sales tax, income tax and corporation tax could actually foster the most productive kind of rich people. I don’t see the clear difference between land and say stock market shares. If you were saving using a private pension scheme then you would get far more shares per $ if share prices were lower and get far more $ in dividends per year if stock were cheaper.

“No, according to MMT they do not need to borrow. The difference is significant.”

Even though they spend by crediting bank accounts electronically? Bonds are issued in the same way, crediting some account at the central bank.

Q8. Why does the government issue bonds?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4J0j5VwnD7I

stone says:

It would.

And why should governments tax wealth that they have done nothing to help accumulate?

And I’m guessing that your guess is wrong!

There are two enormous differences: firstly companies can’t issue more land – it is occasionally possible to reclaim a bit, but the basic amount available remains almost constant. Secondly not everyone needs shares, but land is essential.

PZ says:

Yes.

Everything’s done electronically these days – it doesn’t alter my point. Although MMT says sovereign governments don’t need to borrow, the fact remains that they don’t go by what MMT says, and sovereign governments borrow just as much as their non sovereign counterparts.

The technical standard of that video is atrocious! Not only is the picture distorted, but the background whistling sound makes it almost unwatchable!

Aiden “And why should governments tax wealth that they have done nothing to help accumulate?”

Aiden “And why should governments tax wealth that they have done nothing to help accumulate?”

Actually the value of assets is massively influenced by gov spending. Without progressive taxation, gov deficit spending gets converted into asset price inflation. All a wealth tax would do would be to limit asset price inflation so that gains by asset holders were limited to those from genuine creation of valuable new resources rather than just price inflation of pre-existing assets.

“There are two enormous differences: firstly companies can’t issue more land – it is occasionally possible to reclaim a bit, but the basic amount available remains almost constant. Secondly not everyone needs shares, but land is essential”

-If a modern human was left alone in the world with nothing but land they would struggle and probably die. We need what companies do just as much as we need land. The number of workers is just as finite a resource as the amount of land.