I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

How are the laboratory rats going?

I am all done writing letters – at least for today. I forgot to send both. I noted someone mentioned that he had never read any admissions of error from me. True enough. Over the course of my academic career I have made many predictions and none have turned out to be qualitatively wrong (sometimes the quantum us shaky but the direction is correct). But I am not trying to sell tickets for myself. Economists like me who comment regularly on current affairs are always subject to empirical scrutiny. So I am regularly putting my neck on the line – in written word (blog, Op-Eds etc) and speech (presentations, media interviews etc). So far so good. I note that a correct empirical observation doesn’t mean the underlying theoretical explanation which might have motivated the prediction is correct. But it is a lot better than missing the empirical boat altogether and suggests that there is some worth in the theoretical framework being employed. From a personal perspective the current period of economic policy is very shattering (if you share my values about the dignity of work etc). But from an intellectual perspective, as an economic researcher, the current period is very interesting. It is providing us with real world data which directly relates to theoretical statements made by economic schools of thought. So I am keeping a running tally of how the laboratory rats are going? You can judge which theoretical structure you consider useful yourself when thinking about what is happening at present.

Governments are in full-scale austerity mode at present. Neoliberals claim that governments, like households, have to live within their means. They say budget deficits have to be repaid and this requires onerous future tax burdens, which force our children and their children to pay for our profligacy. They argue that government borrowing (to “fund” the deficits) competes with the private sector for scarce available funds and thus drives up interest rates, which reduces private investment-the so-called “crowding out” hypothesis.

And because governments are not subject to market discipline, neoliberals claim, public use of scarce resources is wasteful. Finally, they assert that deficits require printing money, which is inflationary.

But they go further than this. They claim that quite apart from these alleged negative impacts, deficits are not required to achieve the aims of the Keynesians. It used to be considered non-controversial that government deficits could stimulate production by increasing overall spending when households and firms were reluctant to spend. In a bizarre reversal of logic, neoliberals talk about an “expansionary fiscal contraction” – that is, by cutting public spending, more private spending will occur.

This assertion comes with the fancy name of “Ricardian Equivalence,” but the idea is simple: Consumers and firms are allegedly so terrified of higher future tax burdens (needed, the argument goes, to pay off those massive deficits) that they increase saving now to ensure they can meet their future tax obligations. So increased government spending is met by reductions in private spending-stalemate. But, neoliberals argue, if governments announce austerity measures, private spending will increase because of the collective relief that future tax obligations will be lower and economic growth will return.

I could provide quotes from leading politicians (from the UK Prime Minister down) and leading economists (Nobel Prize winners and up – ooh, sorry to be so disrespectful) supporting this logic.

These conservatives, some of whom were direct beneficiaries of bailout packages in the early days of the crisis, tell us that our governments are bankrupt, that our grandchildren are being enslaved by rising public debt burdens and that hyperinflation is imminent. Governments are being pressured to cut deficits despite strong evidence that public stimulus has been the major source of economic growth during the crisis and that private spending remains subdued.

Austerity will worsen the crisis, because it is built on a lie. Public deficits do not cause inflation, nor do they impose crippling debt burdens on our children and grandchildren. Deficits do not cause interest rates to rise, choking private spending. Governments cannot run out of money.

But the empirical world is continually spitting out data that allows us to judge the veracity of these claims and counter-claims.

In that context, the neoliberal narrative has run into some inconvenient facts. Interest rates remain low. In most of the developed world, inflation is falling and where it is rising, it is due energy and food costs rising rather than excessive deficits.

But what about Ricardian Equivalence?

Should we not be seeing private sector confidence and spending rising by now – especially in the UK which is now 2 budgets into austerity and in Ireland which has been hacking away in the name of Ricardo since early 2009?

If you are familiar with the theoretical discussion relating to government budget constraints, debt dynamics etc leading to Ricardian Equivalence then you can now skip down to the section headed “How is this theory stacking up?” The conceptual part of the blog is for those needing a refresher or some more advanced understanding.

Conceptual framework

The theory in a nutshell is this. Government deficits have to be backed by debt-issuance. In the mainstream framework this is drawn from the government budget constraint (GBC) literature which considers a national government to be like a super-household – that is, facing the same constraints but just bigger in scale.

I have outlined the logic before but to make sure readers understand it here it is in summary.

In the mainstream approach, the GBC framework is used to analyses the so-called “financing” choices governments face when spending. The GBC equation says that the budget deficit in year t is equal to the change in government debt over year t plus the change in high powered money over year t. So in mathematical terms it is written as:

which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit = Government spending + Government interest payments – Tax receipts must equal (be “financed” by) a change in Bonds (B) and/or a change in high powered money (H). The triangle sign (delta) is just shorthand for the change in a variable.

However, once we strip this off the erroneous theory (that governments are like households and have to “finance” their spending) then the GBC is a n accounting statement. In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, this statement will always hold. That is, it has to be true if all the transactions between the government and non-government sector have been correctly added and subtracted.

So in terms of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), the previous equation is just an ex post accounting identity that has to be true by definition and has no real economic importance.

But for the mainstream economist, the equation represents an ex ante (before the fact) financial constraint that the government is bound by. The difference between these two conceptions is very significant and the second (mainstream) interpretation cannot be correct if governments issue fiat currency (unless they place voluntary constraints on themselves to act as if it is).

In fact, the mainstream economists know that there is no constraint – what they really want to say is that using ΔH to fund government spending is inflationary and therefore undesirable. They should be more open about that so that we can move beyond it being a debate about constraints and discussing when inflation becomes possible.

So in mainstream economics, money creation (ΔH) is depicted as the government asking the central bank to buy treasury bonds which the central bank in return then prints money. The government then spends this money. The reality might be that the treasury would instruct the central bank to credit some bank accounts and some intra-government accounting record would be altered. The accounting is of no interest to us economists in this context.

The mainstream however claim that if governments increase the money growth rate (they erroneously call this “printing money”) the extra spending will cause accelerating inflation because there will be “too much money chasing too few goods”! Of-course, we know that proposition is only valid if there is full employment of all resources. Most economies are typically constrained by deficient demand (defined as demand below the full employment level) and they respond to nominal demand increases (growth in spending) by expanding real output rather than prices. There is an extensive literature pointing to this result.

So when governments are expanding deficits to offset a collapse in private spending, there is plenty of spare capacity available to ensure output rather than inflation increases. You will also appreciate that the inflation risk comes from the spending – not what accounting gymnastics are performed – that is, whether the government “borrows from itself” (exchanges of accounting information between treasury and the central bank) or borrows from the public (swapping a bank reserve for a bond account).

These operations neither increase or decrease the risk of inflation associated with the spending. What matter is whether there is spare capacity in the economy to increase production when a spending increase enters the economy. If there is then the inflation risk is low to non-existent. If there isn’t then the inflation risk is high – bond issuance or not!

But not to be daunted by the “facts”, the mainstream claim that because inflation is inevitable if “printing money” occurs, it is unwise to use this option to “finance” net public spending.

Hence they say as a better (but still poor) solution, governments should use debt issuance to “finance” their deficits. Thy also claim this is a poor option because in the short-term it is alleged to increase interest rates and in the longer-term is results in higher future tax rates because the debt has to be “paid back”.

This last claim is the basis of Ricardian Equivalence. I have covered the arguments in detail in the following blogs – Will we really pay higher taxes? and Will we really pay higher interest rates? and so won’t repeat them here other than to keep context.

The mainstream textbooks are full of elaborate models of debt pay-back, debt stabilisation etc which all claim (falsely) to “prove” that the legacy of past deficits is higher debt and to stabilise the debt, the government must eliminate the deficit which means it must then run a primary surplus equal to interest payments on the existing debt.

A primary budget balance is the difference between government spending (excluding interest rate servicing) and taxation revenue.

The standard mainstream framework, which even the so-called progressives (deficit-doves) use, focuses on the ratio of debt to GDP rather than the level of debt per se. The following equation captures the approach (which can be derived from the GBC is you have mathematical skills):

In English, this just says that the change in the debt ratio (the term on the left of the equals sign) is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side of the equals sign which are:

- The difference between the real interest rate (r) and the real GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio.

- The ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP.

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate. Real GDP is the nominal GDP deflated by the inflation rate. So the real GDP growth rate is equal to the Nominal GDP growth minus the inflation rate.

This standard mainstream framework is used to highlight the dangers of running deficits. But even progressives (the doves) use it in a perverse way to justify deficits in a downturn balanced by surpluses in the upturn.

So the GBC says that the change in government debt over year t (which is just a general index for the current period, so t-1 is last period and so on.) is equal to the budget deficit in year t. The GBC links the change in debt to the initial debt outstanding (Bt-1, government spending (G) and taxation (T).

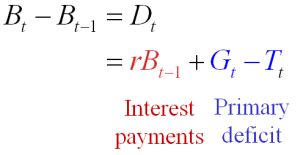

Usually the deficit is decomposed into two constituent parts as depicted in the following graphic:

So the change in debt (Bt-Bt-1 equals the deficit (D) which can be further decomposed into the interest payments on the past debt outstanding (rBt-1) plus the primary deficit (second line of the equations).

This gives the current debt level (third line of the equations) equal to (1+r) times the starting debt plus the primary deficit:

That is all background.

The Ricardian Equivalence idea goes back to David Ricardo’s C19th discussion as to whether households (more generally the private sector) considered government debt as part of their net wealth. Ricardo argued that they might not because they would also factor in that they would eventually have to pay it back via higher taxes.

This idea was revived in 1974 by Robert Barro who added some mathematics to the idea and if they face “perfect capital markets and infinite horizons” will accurately anticipate all future taxes and discount the debt holdings as wealth.

So the idea is clear – the government runs a deficit (tax cuts and/or spending increases) to stimulate the economy and the non-government sector, anticipating that over the lifetime of the agents within this sector taxes will have to rise to exactly pay the deficit back (manifested as the public debt), start saving now. The net effect is that there is no stimulus.

There are various ways of depicting this. Here are some of the stylisations. Take a case where the private sector has to pay back the debt in its entirety after say t periods.So the government waits t years before it increases taxes and repays the debt back.

Start with zero public debt after a long period of balanced budgets. In Year 0, the government cuts taxes by 1 (billion). At the end of the year public debt rises to 1 billion. What happens as a result?

In Year 1, the primary deficit is zero (tax cut occurred in Year 0) and the outstanding debt at the end of year 1 is the outstanding debt in Year 0 (= 1 billion) plus the interest paid on that debt (r).

In mathematical terms (for those who prefer it) the GBC gives the following result:

In English, the current stock of public bonds outstanding at the end of Year 1 (B1) equals the stock of bonds carried over from Year 0 (B0) plus the interest (r) paid on those carried over bonds. The 0 is the assumed primary budget balance. So only interest payments on debt in Year 0 are adding to the debt in Year 1.

I can show the maths for the next several years leading up to Year t but it is a trivial exercise. The important understanding that despite the fact that taxes were lower in only the first year and the primary budget balanced thereafter, debt has steadily accumulates at a rate equal to the interest rate.

Despite the fact that taxes were lower in only the first year and the budget balanced thereafter, outstanding public debt has steadily accumulated at a rate equal to the interest rate. The reason is that even though the primary deficit is zero each year and not adding to debt, the debt servicing on outstanding public debt is positive. Each year the government must issue more debt to pay the interest on existing debt.

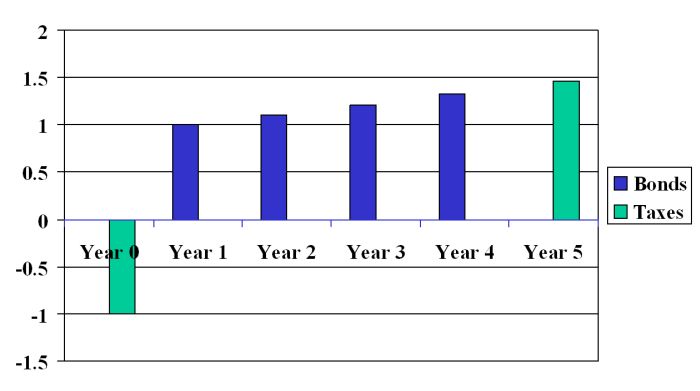

The following graphic shows what happens in a five-year payback sequence if r=0.10 (as an example). You can see that in Year 5, the primary surplus has to be much greater than the initial deficit.

In general, the mainstream claim that an increase in the deficit in the past must eventually be offset by an increase in taxes in the future. The higher the real interest rate or the longer the government waits to increase taxes the higher is the eventual increase in taxes.

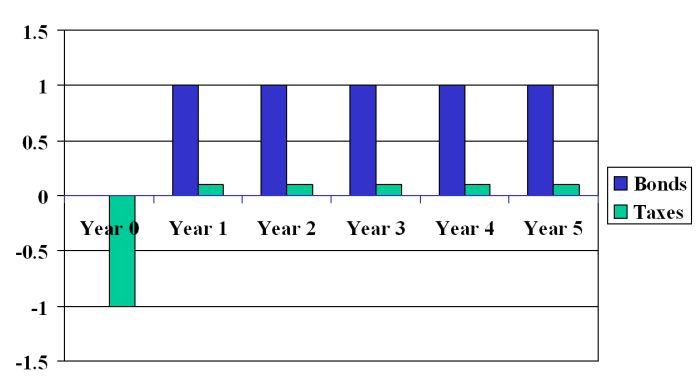

What happens in the government merely aimed to stabilise the debt from Year 1 onwards? Again I could write this out succinctly in mathematical form but in the interests of inclusion the following explanation arises.

In order to avoid the debt growing, each subsequent primary surplus must equal the debt servicing costs. This means that taxes are permanently higher from Year 1 on and it doesn’t matter if the government waits until Year t to stabilise. All this assumes that spending is unchanged.

The following graph captures this scenario. The point is that the mainstream claim that the government may not actually pay the debt off for the higher taxes to be punitive. Even with debt stabilisation they says taxes have to be higher in the period after the deficit.

So the mainstream claim that the legacy of past deficits is higher debt (because of their bias against Δ. To stabilise the public debt, the government must eliminate the deficit and then must then run primary surpluses equal to interest payments on the existing debt forever.

When an economy is growing it makes more sense to consider the ratio of debt to GDP rather than the level of debt per se. Which is the GBC framework presented above (I repeat the equation here):

Say the primary deficit is zero. Then public debt level increases at a rate equal to the interest payments as explained before. But the public debt ratio (that is, the level of the debt scaled by GDP) increases at a rate equal to the difference between r and g (g is the real growth of the economy). So the growing interest payments drive the top of the ratio (debt) while the growth of the economy deflates that numerator (debt). So a growing economy can absorb more debt and keep the debt ratio constant.

It follows that the public debt ratio will be higher:

- The higher is the rate of interest.

- The lower is rate of real GDP growth.

- The higher is the initial debt ratio.

- The higher is the primary deficit to GDP.

Which isn’t rocket science is it?

The mainstream then uses this analysis to argue that high government debt leads to lower capital accumulation and ever-increasing taxes.

Assume a debt ratio of 100 per cent. Let r = 3 per cent and g = 2 per cent. Also assume a primary surplus of 1% of GDP. What does this economy face? If you substitute the assumptions into the model you will see that this is a debt ratio stabilising position – the primary surplus exactly offsets the interest payments (as a percent of GDP).

But what if the financial markets suddenly demanded a risk premium on domestic public bonds. The mainstream argue that the interest rates will rise. If the rising rates also push down the real GDP growth rate you can see the logic emerging.

Now the primary surplus has to rise further to stabilise the debt ratio and the so-called vicious circle of debt arises. The sharp fiscal contraction leads to recession. The government becomes unpopular and uncertainty drives further rate rises. It becomes even harder to stabilise debt as interest rates rise and real growth falls.

What Barro said was that the government does “our work” for us. It spends on our behalf and raises money (taxes) to pay for the spending. When the budget is in deficit (government spending exceeds taxation) it has to “finance” the gap, which Barro claims is really an implicit commitment to raise taxes in the future to repay the debt (principal and interest).

Under these conditions, Barro then proposes that current taxation has equivalent impacts on consumers’ sense of wealth as expected future taxes.

So the government spending has no real effect on output and employment irrespective of whether it is “tax-financed” or “debt-financed”. That is the Barro version of Ricardian Equivalence.

Taking tax cuts as an example, Barro wrote (in ‘Are Government Bonds Net Wealth?’, Journal of Political Economy, 1974, 1095-1117):

This just means that lower taxes today and higher taxes in the future when the government needs to pay the interest on the debt; I’ll just save today in order to build up savings account that will be needed to meet those future taxes.

Ricardian Equivalence can be attacked on two fronts: (a) theoretical; and (b) empirical.

On a theoretical level, the theory imposes highly restrictive assumptions which have to hold in entirety for the logical conclusion Barro makes to follow? Even without questioning whether his reasoning is a sensible depiction of the basic operations of a modern monetary system, we can examine the plausibility of the assumptions.

Should any of these assumptions not hold (at any point in time), then his model cannot generate the predictions and any assertions one might make based on this work are groundless – meagre ideological statements.

The assumptions that have to hold are: First, capital markets have to be “perfect” (remember those Chicago assumptions) which means that any household can borrow or save as much as they require at all times at a fixed rate which is the same for all households/individuals at any particular date. So totally equal access to finance for all.

Clearly this assumption does not hold across all individuals and time periods. Households have liquidity constraints and cannot borrow or invest whatever and whenever they desire. People who play around with these models show that if there are liquidity constraints then people are likely to spend more when there are tax cuts even if they know taxes will be higher in the future (assumed).

Second, the future time path of government spending is known and fixed. Households/individuals know this with perfect foresight. This assumption is clearly without any real-world correspondence. We do not have perfect foresight and we do not know what the government in 10 years time is going to spend to the last dollar (even if we knew what political flavour that government might be).

Third, there is infinite concern for the future generations. This point is crucial because even in the mainstream model the tax rises might come at some very distant time (even next century). There is no optimal prediction that can be derived from their models that tells us when the debt will be repaid. They introduce various stylised – read: arbitrary – time periods when debt is repaid in full but these are not derived in any way from the internal logic of the model nor are they ground in any empirical reality. Just ad hoc impositions.

So the tax increases in the future (remember I am just playing along with their claim that taxes will rise to pay back debt) may be paid back by someone 5 or 6 generations ahead of me. Is it realistic to assume I won’t just enjoy the increased consumption that the tax cuts now will bring (or increased government spending) and leave it to those hundreds or even thousands of years ahead to “pay for”.

Certainly our conduct towards the natural environment is not suggestive of a particular concern for the future generations other than our children and their children.

If we wrote out the equations underpinning Ricardian Equivalence models and started to alter the assumptions to reflect more real world facts then we would not get the stark results that Barro and his Co derived. In that sense, we would not consider the framework to be reliable or very useful.

But we can also consider the model on the basis of how it stacks up in an empirical sense. When Barro released his paper (late 1970s) there was a torrent of empirical work examining its “predictive capacity”.

It was opportune that about that time the US Congress gave out large tax cuts (in August 1981) and this provided the first real world experiment possible of the Barro conjecture. The US was mired in recession and it was decided to introduce a stimulus. The tax cuts were legislated to be operational over 1982-84 to provide such a stimulus to aggregate demand.

Barro’s adherents, consistent with the Ricardian Equivalence models, all predicted there would be no change in consumption and saving should have risen to “pay for the future tax burden” which was implied by the rise in public debt at the time.

What happened? If you examine the US data you will see categorically that the personal saving rate fell between 1982-84 (from 7.5 per cent in 1981 to an average of 5.7 per cent in 1982-84).

In other words, Ricardian Equivalence models got it exactly wrong. There was no predictive capacity irrespective of the problem with the assumptions. So on Friedman’s own reckoning, the theory was a crock.

Once again this was an example of a mathematical model built on un-real assumptions generating conclusions that were appealing to the dominant anti-deficit ideology but which fundamentally failed to deliver predictions that corresponded even remotely with what actually happened.

Barro’s RE theorem has been shown to be a dismal failure regularly and should not be used as an authority to guide any policy design. Please read my blog – Deficits should be cut in a recession. Not! – for more discussion on this point.

How is this theory stacking up?

I last examined this question towards the end of last year. Please read my blog – Ricardians in UK have a wonderful Xmas – for more discussion on this point.

Business confidence in the UK

We have been observing business confidence falling steadily over the last year in the UK after showing signs of picking up as the fiscal stimulus supported economic growth in late 2009 going into 2010.

A Bloomberg financial report (March 27, 2011) – U.K. Business-Confidence Index Falls to Lowest in Two Years – says it all in the title.

The Report says that:

U.K. business confidence declined in March to the lowest in two years, suggesting the economy may struggle to gather strength in the second quarter … The share of companies that were less optimistic about economic prospects increased to 44 percent from 36 percent in the previous month.

The article noted that there might be some modest “weather-related bounce” in growth “after the fourth-quarter contraction”. But across the economy – companies, manufacturers, retailers – confidence has collapsed.

By now, all these “tax payers” should be feeling strongly positive given the UK Government’s austerity push and demonstrating that they are ready to fill the spending gap left by the public withdrawal.

They are not. They are not Ricardian!

UK consumers

In the UK Guardian article (March 29, 2011) – Grocery sales slow as UK shoppers economise – we read that:

Britons have been cutting back on groceries, data showed on Tuesday, adding to signs of a rapid deterioration in consumer confidence which, economists fear, could derail an economic recovery …

British retailers have reported a sharp slowdown in demand since the start of the year as prices climb and government austerity measures start to bite.

By now, the British consumer should be expanding their spending. You might say that the rising inflation (driven by supply factors and stupid austerity measures – VAT increases) is causing the loss of confidence.

But economists always note that inflation discourages saving and promotes consumption – because things get more expensive the longer you delay the purchase (there is more detailed explanations but that is it in a nutshell).

So grocery shoppers are not Ricardian!

In the UK Guardian article (March 29, 2011) – Thomas Cook – UK demand for foreign holidays is slowing sharply – we read that:

Demand for foreign holidays has fallen sharply in the UK in recent months as weak consumer confidence continues to bite, Thomas Cook warned on Tuesday …

Although the UK recession officially ended more than a year ago, consumer confidence has slumped to its lowest level in nearly two years – due in part to growing inflationary pressures and austerity cutbacks. Economists have warned that this means many “big ticket” purchases are being shelved.

So travellers are not Ricardian!

I also point out that the Irish economy has been contracting for the last three years and its banks are now requiring further capital injections so bad is the situation in that country.

All the evidence shows that firms are currently very pessimistic and will not expand employment and production until they see stronger growth in demand for their products. Consumers are also pessimistic because they worry about losing their jobs. They are also heavily indebted and are trying to save to reduce risks should they become unemployed. By cutting public spending, this pessimism will only deepen.

The greatest neoliberal lie is in denial of all the facts relating to human psychology.

The on-going indicators from Ireland and now Britain – poor growth figures and surveys indicating growing pessimism among private firms and consumers – are already undermining the substance of their respective government’s austerity strategy.

The only way economies grow is when companies expand in response to increasing demand for their products. When private demand is subdued, the only way to increase growth is for government to spend, via deficits. Austerity will just withdraw the lifeline that has been keeping our economies growing in the past year or so.

Conclusion

The current period is thus providing a very good arena for assessing some of the key notions. There has been a polarisation in the predictions coming from various schools of thought. The mainstream economics position is fairly clear. The narrative is being destroyed by the facts as they emerge. Sooner or later people will realise that.

For MMT, so far, it provides the best explanation of what has happened and remains concordant with the facts as they emerge.

Judge for yourselves.

That is enough for today!

“The theory in a nutshell is this. Government deficits have to be backed by debt-issuance.”

It seems to me that the theory in a nutshell is this: all NEW medium of exchange has to be the demand deposits created from debt, whether private or gov’t.

The question is what are the economic assumptions behind this theory.

“It follows that the public debt ratio will be higher:

The higher is the rate of interest.

The lower is rate of real GDP growth.

The higher is the initial debt ratio.

The higher is the primary deficit to GDP.

Which isn’t rocket science is it?”

Is the rate of real GDP growth from the demand side or the supply side?

Dear Fed Up (at 2011/03/30 at 17:39)

You asked about the rate of real GDP growth in the Public Debt ratio formula:

The System of National Accounts (SNA) unites the supply (output) measures and demand side (expenditure) measures. So ignoring what is known as the statistical discrepancy – which emerges as production and spending records are assembled to create the measure of GDP each quarter – the two measures are the same.

best wishes

bill

bill,

“they respond to nominal demand increases (growth in spending) by expanding real output rather than prices. There is an extensive literature pointing to this result.”

Is this detailed anywhere?

We’re constantly asked for it when we respond to the real ‘crowding out’ argument with the ‘businesses will more likely expand real output than put up prices’ line.

I’d like to be able to say ‘as shown, here, here and here’.

Practically all the debates on blogs boil down to ‘production won’t expand to absorb the spending because there hasn’t been enough previous investment’. There appears to be the expectation of a limit on the expansion of the economy and how rapidly that can happen.

It’d be really useful to have some data to back up the theory.

Can anybody explain how delta H disappears in the GBC in a system that pays interest on reserves?

Is the assumption that H is constant?

I believe Keynes realised that financing deficits with new money was better than financing them with debt, but he reckoned those surrounding him were too stupid to appreciate the point. Seems the “stupids” are still with us. So he kept rather quite about this point. But I can’t remember where I read that. Can anyone supply me with chapter and verse from Keynes’s (or someone else’s) writing?

Re the Ricardain idea, this is a classic example of academia at its worst: people with no grasp of the real world, and interested primarily in furthering their careers by counting the number of angles dancing on a pinhead.

In other words the idea that the average household or employer knows what the deficit is per person, and “saves” so as to be able to repay the resulting national debt increase, is straight out of Alice in Wonderland, which is where many academics live.

Neil: I think the answer to your question is that during a recession there is ample quality labour available, plus ample capital equipment (certainly during the initial months of a recession). Thus any increase in demand will translate into more output rather than higher prices. Having said that, the current recession has lasted longer than it should have, and I’ve seen evidence that American’s stock of capital equipment has shrunk, by a percent or two. But that’s not enough to prevent a substantial reduction in US unemployment.

“Neil: I think the answer to your question is that during a recession there is ample quality labour available, plus ample capital equipment (certainly during the initial months of a recession). Thus any increase in demand will translate into more output rather than higher prices”

Thanks Ralph. Yes that’s the theory. I’m looking for the facts to back that up.

Because the next response is that ‘output can’t expand because there hasn’t been enough investment’. The neo-classical people seem to believe that there is a limit based on the sum of previous investment ie some ratio of ∑I

Hence why you get all the social democrats banging on about investment banks – rather than taking the obvious approach of dangling a large dollop of demand in front of the noses of entrepreneurs.

“they respond to nominal demand increases (growth in spending) by expanding real output rather than prices. There is an extensive literature pointing to this result.”

Yes, I’d also be interested to read the “extensive literature” on this matter – perhaps a future blog post Bill! I can see why it makes sense logically, but I’d like to see whether the theory translates in the real world…

Re: Ricardian Equivalence.

Barro argues that if the older generation was planning on making an intergenerational transfer to the younger generation — he gives the example of spending on education — that they will then increase the size of the transfer by the value of the bonds, in order to offset the future tax liabilities. Notice that he is confusing a real transfer — spending on education — with a nominal transfer.

Suppose that they *do* give the younger generation their government bonds. How is that supposed to nullify the effects of the deficit spending? Were they supposed to eat the bonds? Bury the bonds in their coffins?

In aggregate, they have no choice *but* to give the bonds to the younger generation, even if they were not planning on making any real transfer.

The whole paper is a shambles confusing nominal with real. The risk is that they will decrease the (real) transfer — spending on education — and give the bonds to the younger generation instead. And what Barro actually shows is that the (voluntary) real transfer will not be crowded out by the (forced) nominal transfer, and as a result, there is never any (generational) pain in paying taxes, because each generation will be given enough in bonds to exactly offset the future tax liabilities, should those tax liabilities come due in a given period.

There is only tax pain within the generation, as the distribution of bonds is not equal — which is another reason for progressive taxes.

To talk about the effects of deficit spending when there is an output gap, you would need a model that featured an output gap, and then showed whether or not a policy of deficit spending, together with taxation, closes this gap or otherwise improves welfare. Barro assumes a classical market clearing model.

But even the simplest model of an output gap shows that countercyclical deficit spending increases welfare, if you allow that smoothing nominal incomes increases welfare.

Suppose we assume that for every generation, in each period, there is a 50% chance that they will earn only $10 of nominal income and a 50% chance that they will earn $20 of nominal income. Assume each generation lives for 2 periods.

In that case, even with perfect credit markets, each generation will not be able to fully smooth its nominal income because it has a finite life and cannot pass debts onto the subsequent generations.

Because it has a finite life, there is a risk that it will need to repay debt in a bad period, so they will not fully smooth their nominal income by borrowing more — e.g. expanding credit — in the low income period, and repaying debt — contracting credit — in the high income period.

They really need taxes, which are paid as a percentage of income. But if they tried to borrow on those terms, the bank would rightly charge them a risk premium for the 50% chance that they will have less nominal income in the second period as well.

Taxes + deficits are the optimal way to smooth nominal income across time, and it needs to be done by someone who can issue riskless debt and moreover can enforce contracts on all generations, forcing all generations during boom periods to pay more in taxes (as their nominal income is higher). That way, it is still the case that, in each generation, the amount of debt at the end of the period is equal to the amount of future tax obligations, so no harm is coming to future generations by “leaving them with debt”, but at the same time, some generations have their nominal income increased while others have their nominal income decreased to achieve a smooth path of nominal income across time.

Only government can force that type of intergenerational cooperation, and only the government can keep rolling-over debt so that the law of large numbers applies and no risk premium is charged. Government is able to weather a whole string of bad nominal income periods, whereas a single generation is not.

That gain — reducing nominal income uncertainty for *every* generation, together with the increase in cumulative real output as a result of the smoothing, is the true net wealth represented by public holdings of government debt.

I have a couple of amateur question about MMT and inflation.

First, MMT theorists frequently tell us about the conditions that will not cause inflation. And specifically, they (and others) tell us that “printing money” will not cause inflation if we are not at full employment. So what I would like to know is what, according to MMT, are the conditions that will cause inflation. Is there a general MMT theory of the causes of inflation?

Second, suppose we divide the economy into two sectors, A and B. And suppose that while sector A is not at full employment, sector B is at full employment. So the whole economy is below full employment. Suppose now that the government is running a deficit during some time period p, and happens to be increasing spending during p in sector B. If this were to happen, could you get inflation in sector B, and also the economy as a whole, even though the economy is not at full employment?

I ask these questions because inflation is the issue that comes up the most when I try to discuss MMT ideas with others. They apply a quantity theory of money instinctively, and therefore assume that you can’t avoid inflation if deficits are “financed” by money creation rather than taxation or borrowing. Also, anyone old enough to recognize the period of stagflation in the 70’s is not convinced by the claim that high unemployment is barrier against inflation.

According to the absurd OBR the lab rats are going to be cured by a massive injection of personal debt ie households will start acting like tax and spend governments as governments start acting like households. A good summary is found here.

The OBR’s projections are rather rosy to say the least.

Dan, good questions. To add, I would want to know how do you avoid inflation at full employment from all the deficit spending and the interest associated with the debt that occurred before we reached full employment. Is decreasing spending over time and/or raising taxes enough? Answers might be offered in this blog post, but I haven’t read it yet :). Will do ASAP though.

For some reason I’ve had a bit of a problem in getting fully comfortable with what the idea of Ricardian equivalence is supposed to mean.

Does it actually mean that there is an economics model which assumes that government debt (NFA I guess) is presumed to be zero at some distant future point?

Surely I must be wrong on that.

Because it seems inconceivable to me that there could be an economics model that is so fundamentally moronic.

It could be recognized as such by any intelligent child who has passed grade 3 arithmetic and started his first savings account.

So I must be wrong.

“So what I would like to know is what, according to MMT, are the conditions that will cause inflation.”

Aggregate demand in excess of aggregate supply causes demand inflation within a currency zone. That is the limit of government deficits.

“And suppose that while sector A is not at full employment, sector B is at full employment.”

If you apply government spending via the job guarantee to that situation you will see that it makes sector A automatically operate at full employment by directing the spending there, but does nothing to sector B.

That’s one of the reasons why job guarantee is such a good idea – it is simply an enhancement to the existing automatic stabiliser system – and is slightly more targeted than across the board tax cuts.

As an American, I can say I’ve never met a single person who ever saved for future taxes.

People are desperately trying to pay down debt and deal with underwater mortgages.

Even the people who believe the national debt is a crippling burden (most people) don’t adjust their behavior at all.

Haven’t even some neo liberal economists moved beyond this? It doesnt pass the straight face test.

they respond to nominal demand increases (growth in spending) by expanding real output rather than prices. There is an extensive literature pointing to this result

I bet there is an extensive literature pointing at the opposite result as well.

JKH,

You are right! I mean wrong! I’m not sure what I mean!

The intertemporal government budget constraint says that the present value of govt spending must be less than or equal to the present value of it tax receipts net of transfers and its initial wealth.

Given a growing economy, this implies that a constantly growing stock of public debt will satisfy the constraint if its growth rate (that is, the growth rate of the real stock of public debt) is less than that of the real interest rate on that debt.

At no point does the debt need to go to zero, according to this theory.

Ricardian Equivalence is something extra-you could think of it as being like Miller-Modigliani for the government sector.

RE says that, given the govt budget constraint and a fairly stringent set of assumptions (no private credit constraints, private sector & govt borrow at same rate, etc), it is immaterial whether the govt finances its consumption by borrowing now and taxing later, or by taxing now-the scheduling of taxes does not matter, because the present value of private income (i.e. private wealth) is the same regardless.

You can see this by writing the constraint in a simple two period model as,

C_1 + C_2 / (1 + r) = (Y_1 – G_1) + (Y_2 – G_2) / (1 + r)

Private wealth is the difference between private endowments and public spending. The financing mix of borrowing vs taxes does not enter into the equation here: the time profile of taxation has no effect on private wealth.

The Ricardian Equivalence proposition is the idea that the private sector fully internalizes this budget constraint. If the government reduces taxes, but not spending, then it must increases taxes in the future. Private wealth does not change unless public spending changes. So the private sector might see through this and realize that the principal and interest it earns lending to the govt is matched by the taxes levied against it to service the debt. Households hold public bonds as assets but these are exactly offset by the value of their tax liabilities.

Brilliant post! Should be made mandatory reading for Economics 101.

However, I have one doubt that has been nagging me for some time (I’ve raised in other blogs, but no one commented on it…), concerning the proposal that has been made by some MMTers for the government to simply stop issuing debt and to credit bank accounts (high powered money) to pay 100% for its expenditures.

If that was to occur – if the Government stops issuing bonds – how is the private sector supposed to be able to accumulate Net Financial Assets (NFAs) on the public sector?

I gather that according to MMT, in a situation of equilibrium in the current account, the “normal” situation in an economy with fiat currency and free floating would be a budget deficit with net saving of the private sector, that will thus build every year a creditor position against the government.

But if no interest-paying T-bonds or notes are available and the natural interest rate really is zero (another MMT point) then unless the inflation rate is also zero or below zero – something I know MMTers definitely do not endorse – the private sector will be unable to have growing claims against the Government. It would be reduced to deposits at zero interest, alongside a positive if low inflation rate.

Isn’t it then the case that issuing T-bonds will always be necessary in order to enable the private sector to build claims on the public sector and thus keep its “animal spirits” and investing behaviour alive?

Government bonds are the only asset that is simultaneously risk-free and interest-bearing. All players in the private sector – individual investors, corporations, banks, pension funds – need to have some part of their portfolios invested in a risk-free investment. If you scrap this instrument it is quite possible that the private sector as a whole will end up losing confidence in the system.

Just imagine a world where portfolios necessarily have to be composed of risky assets, 100%. It would be vastly different from our world. Who knows what would happen to capitalism under these circumstances?

In a sense one could say that the Government is the ultimate insurer of society. That’s the reason functional (as opposed to dysfunctional) neoliberal societies will never exist in the real world. Financially, the government has to offer society a safe interest paying asset, because it is the only entity with the capacity to issue that asset and honour its promise. After all, as MMTers rightly say, the Government can never go broke!

So my question is: isn’t there some inconsistency between the (correct!) MMT claim according to which the normal condition of an economy is to operate with a private sector surplus and a budget deficit – with the private sector soundly building NFAs over the public sector – and the statements of some of its proponents appealing for an end to debt issuance, the integration of the Central Bank into the Treasury department and the pure and simple crediting of bank accounts via computer keyboards every time the government spends?

To make it clear, I don’t think these proponents are wrong from an operational point of view. The government could really end debt issues if it wanted to. It’s just that it seems to be a bit puzzling why a government would decide to implement a measure whose immediate practical consequence would be to deprive the private sector from a much-needed risk-free, interest-paying financial asset.

So, as I understand it Vimothy, the Ricardian equivalence proposition incorporates both the idea that current borrowing must be balanced by future taxes and the idea that the first claim is fully internalized in private sector expectations.

But of course, whether such an expectation actually exists is a purely subjective phenomenon, that has no logical connection with whether or not the first claim is true. One might as well say that fiscal expansion won’t work in the US because Americans believe we are in the End Times, and believe they need to hoard their income to by food during the Apocalypse.

So I guess one of the best ways of preventing Americans from hoarding additional income as a hedge against future taxes is not to promote quack theories according to which current borrowing must be repaid with future taxes.

If you apply government spending via the job guarantee to that situation you will see that it makes sector A automatically operate at full employment by directing the spending there, but does nothing to sector B.

Neil, that sounds more like an (excellent) prescription for public policy rather than a a merely descriptive economic explanation or prediction about how the actual economy functions. Would it be fair to say that, according to MMT, additional government spending at less than full employment could cause inflation, if the money is spent foolishly and on the wrong goods and services, but <need not cause inflation if the money is spent wisely on increasing the production of goods and services – and hence increasing employment – in those areas of the economy that are running below capacity?

Vimothy’s understanding of the difference b/n RE and IGBC is the same as my take, FWIW.

If sector B has full employment while sector A does not then if the government increases spending on sector B’s goods and services, sector B contracts free resources from sector A (labor and capital) and no inflation will follow.

Neil, Re your request for facts and evidence, this might meet your requirements. It’s a chart showing plant capacity utilisation. This changes more or less in the way my above “theory” suggested. See:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/TCU

Re Social Democrats and other politicians who like interfering in investment decisions, my answer is that it if we managed say 4% unemployment prior to the crunch without politicians’ “expertise” in investment decisions, we can manage 4% unemployment again without such expertise. Plus the history of politicians’ meddling in investment decisions is a catalogue of disasters. So my message to them, to use technical economics jargon, is “get stuffed”.

Dan,

MMT isn’t a magic wand. It’s just a description of the way the money system works in reality.

You have to take that, understand what extra wiggle room that gives you and then design an economic system that uses that room to best advantage. It most certainly isn’t a free lunch. Bad policy can still destroy a country’s economy.

Similarly the description of the nuclear chain reaction in Uranium can be used to build a bomb or power the electricity grid.

“It would be reduced to deposits at zero interest, alongside a positive if low inflation rate.”

Don’t forget that net-saving isn’t saving. Individuals will still be able to save, and receive interest, but the interest will come directly from the returns on Investment – less profit and risk premiums for the banks.

Net saving is S – I, If that sums to zero then that is probably a decent position to be in as there is no leakage.

If the external sector (X-M) is similarly at zero then that is probably a decent position to be in.

Regardless of what the aggregate picture is, within that some people will be long – possibly very long – and some people will be short – possibly very short.

” sector B contracts free resources from sector A (labor and capital)”

That assumes full substitutability, which probably isn’t the case. There will be some stickiness as you approach full capacity where supply side issues start to become more prominent.

If we ever get anywhere near that it would be a good problem to have though!

thanks, Vimothy – that’s very helpful

For JKH:

So, what’s the verdict? is it still inconceivable to you “that there could be an economics model that is so fundamentally moronic.“?

Keith,

The verdict is that if such a model doesn’t exist, then it isn’t fundamentally moronic.

What’s your own verdict on whether or not it exists?

But it sort of looks to me like it exists in the form of Bill’s first stylization chart.

So I’m still trying to connect the dots.

For Neil,

I agree that Investors would still receive interest but only from risky investments since the risk-free asset would not be available anymore. I don’t think this is a very exciting prospect for risk-avoiding investors. Also, portfolios would have to be composed by risky assets, exclusively. That would create many problems for pension funds, endowments, etc. So for all practical purposes I think no government would ever dare to stop issuing public debt.

Maybe RE could use a strong, semi-strong, weak taxonomy.

bueller, bueller, … fullwiler, …. anybody?

I’m dying here.

I’ll try this:

perhaps somebody could tell me in reasonably precise terms what Bill’s first chart (with the bullet tax payment) illustrates in the context of the overall theory of Ricardian equivalence

because Bill’s lead in to that chart certainly suggests it illustrates something

and that something seems to correspond vaguely to what I initially referred to (and I don’t mean that Bill’s illustration is moronic!)

Jose,

“That would create many problems for pension funds, endowments, etc.”

There’s a clue there. Keep thinking that through to its logical conclusion. Pensions use government tax relief to boost their value and government payments on government paper to pay them out when they mature.

So why not just cut out the middleman?

JKH–that just shows that if I lend you a sum of money at a particular interest rate, the amount you owe is going to grow at that rate until you pay it back, even if you don’t borrow any more. In an economy with no growth current deficits imply future surpluses and a balanced budget over the life-cycle of the economy, if the government is to satisfy its intertemporal constraint.

Neil,

I think abolishing the risk-free asset and forcing every investor 100% into risky investments is a very bad idea. Yet that would be a necessary consequence of a decision to stop issuing public debt securities in the future.

MMT seems to be the best description available of how the modern fiat monetary system really works. But the policy proposals introduced by some of its defenders are sometimes, quite needlessly, a bit controversial – to put it mildly. This is a pity, because it might scare otherwise sympathetic observers into rejecting MMT based not on its intrinsic merits but rather on the distrust instilled by iconoclastic policy proposals that are just a result of the personal, idiosyncratic preferences of a small sample of MMTers.

Neil: MMT isn’t a magic wand

The “magic wand” is the ability to issue currency and and to tax as the monopolist. But it only seems like magic if you don’t understand monetary ops, just like technology seems like magic if you don’t understand the science.

If sector B has full employment while sector A does not then if the government increases spending on sector B’s goods and services, sector B contracts free resources from sector A (labor and capital) and no inflation will follow.

Yes, that certainly could happen Jose. But isn’t it possible, depending on the nature of the two sectors, that jobs and productive resources are “sticky” in a way that prevents easy movement of resources from one to another?

Anyway, I think the main point, as Neil says, is that just because MTT implies that the “solvency constraint” is bogus, that doesn’t mean deficit spending as policy is idiot-proof. If you want to increase employment in some particular sector, you should spend the money into that sector.

Jose: This is a pity, because it might scare otherwise sympathetic observers into rejecting MMT based not on its intrinsic merits but rather on the distrust instilled by iconoclastic policy proposals that are just a result of the personal, idiosyncratic preferences of a small sample of MMTers.

We hear this constantly about almost all of MMT. MMT shows how tsy issuance is operationally unnecessary, hence, constitutes a preferential subsidy. MMT shows how the natural rate of interest is zero. MMT shows how a job guarantee works to achieve full employment along with price stability by providing a job offer for anyone willing and able to work at a wage that establishes a price anchor. MMT shows how deficits fill demand leakage. All of these things are vehemently disputed or opposed by some people.

JKH, It might be worth adding that that result doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with Ricardian Equivalence–its more that Ricardian Equivalence has something to do with that result. The intertemporal budget constraint is trying to describe the behaviour of the government. RE is about how the private sector reacts to changes in govt financing given full knowledge of the constraint (in fact, the whole model). Basically, RE is the private sector as economist, solving the optimisation problem for itself and adjusting its behaviour accordingly.

Neil: So for all practical purposes I think no government would ever dare to stop issuing public debt.

The problem is with the $-4-$ deficit offset requirement, which makes it seem as though government has to borrow to finance itself, or else tax to fund itself, which is false. There could conceivable be some argument for tsy issuance for public purpose. I have often said that even with “no bond” the government might still offer retail bonds, called E-bonds (series E and EE) in the US. Warren Mosler would allow up to 30 day T-bills in his proposal.

To Jose and Dan

Where I think Neil is trying to get you to go (correct me if I’m wrong Neil) is to imagine that you either buy an asset with your money or you keep your money, not fearing that you wont later be unable to get money because you will always have access to an income flow. Thats why we save in bonds and stocks, to make sure we have a stock of assets to be able to later liquidate and get a flow of income. So instead of providing bonds the govt just guarantees a minimum income. No need to save up huge stocks of money to assure future income flows.

Do away with unnecessary bonds, provide a minimum income for all (adjusted to cost of living adjustments) and let private activities serve to augment your income and provide the goods which we consume and trade.

This wouldnt result in a “you pretend to work I pretend to pay you” system, rather it would provide a floor below which aggregate demand could never fall and result in businesses competing for your demand rather than businesses competing to see who can get away with paying the least.

Forget about Ricardian Equivalence and laboratory rats. We know follow the Mammothian Equivalence.

When president Mosler announces that since unemployment results from overtaxing, he will lower taxes to go back to full employment like in the good ol’days.

Since we know he will lower taxes as long as there is still unemployment, we save all the extra income coming from the tax cuts.

Hence we increase our NFAs, but unemployment stays at same level which requires further tax cuts. So we can accumulate plenty of NFAs until taxes reach 0. At that point we might increase consumption, unless the president promises to make transfer payments to fight unemployment.

“MMT shows how tsy issuance is operationally unnecessary, hence, constitutes a preferential subsidy (…) All of these things are vehemently disputed or opposed by some people”.

I haven’t anything to oppose to the statement from an operational point of view. Public debt issuance could stop tomorrow, if the State decided so. However, that would deprive people and institutions from investing in an interest-bearing, risk-free asset. So that decision would have consequences that would potentially aggrieve sub-sectors of the population, result in changes in the behavior of certain investors, etc. It would certainly have to be thoroughly thought through before adoption, to check for unintended results and so forth.

In a sense, the government by offering a risk-free asset increases the trust of the population in itself as an institution and in the economic system as a whole. People trust governments to guarantee their investments, they rightly distrust banks to do the same thing. So, why should we finish off that guarantee?

Anyway, all this cannot be central to MMT. MMT proves beyond reasonable doubt that there is no operational need to issue public debt. It is silent on whether, as a matter of policy, governments should issue debt or not. That’s a policy choice, dependent on values and beliefs. It´s a subjective decision. The MMT description, by contrast, is an objective statement about reality.

“If you want to increase employment in some particular sector, you should spend the money into that sector”.

I don’t think this is necessarily so. A large economy will probably always have many sectors near full employment, alongside others well below full utilization of resources. The balance will be aggregate production below aggregate potential output. It would be very hard, perhaps impossible, for the government to fine tune spending only on those sectors below full employment. The solution will then be to inject public spending and/or cut taxes so that aggregate demand will reach the level necessary for actual output to reach potential output.

The economic system itself would take care of the rest, re-allocating resources such as jobs and capital to where they are most needed, without causing generalized inflation in the process.

“I have often said that even with “no bond” the government might still offer retail bonds, called E-bonds (series E and EE) in the US. Warren Mosler would allow up to 30 day T-bills in his proposal.”

Why not allow Treasury Direct to offer cash accounts (paying the Fed Funds rate)?

Vimothy,

“Ricardian Equivalence is something extra-you could think of it as being like Miller-Modigliani for the government sector.

RE says that, given the govt budget constraint and a fairly stringent set of assumptions (no private credit constraints, private sector & govt borrow at same rate, etc), it is immaterial whether the govt finances its consumption by borrowing now and taxing later, or by taxing now-the scheduling of taxes does not matter, because the present value of private income (i.e. private wealth) is the same regardless”.

RE seems to be not much more than a judgment of indifference relative to the spending decisions of the public sector.. According to RE, if the government has deficits with issuance of debt, then the private sector reduces its spending on a one-for-one basis in order to save for the inevitable future payments of taxes. The net result is no change in aggregate demand and thus output.

Question: if the net result is neutral, then why all the fuss about deficits? Proponents of RE should instead keep a detached, indifferent, at most mildly ironic posture as far as government deficit spending decisions are concerned. But they choose to stridently oppose them, instead. This is logically inconsistent and stands in contradiction to the rigorous formal logic – though based on unrealistic assumptions – they insist on applying to their models.

Also, a second consequence of RE models, not much talked.about, arises. If deficit spending is neutral it follows, under the same rigorous logic, that deficit reduction is equally neutral. Governments may reduce spending or increase taxes, but the private sector will match these decisions one-for-one (not more, not less than one for one, remember!) by increasing its spending. So, no recovery of output to full employment levels could possibly happen as a result of deficit-cutting decisions.

Unless, of course, RE decides to add extra assumptions, not present in the original model, to justify such a conclusion. But then, this would not be playing fair, would it? Why not then also add extra assumptions to deny the validity of the primal conclusion about the neutrality of deficit spending? Well, because at this point the whole RE edifice might really start to crumble on its own terms…

I think serious analysts should go after RE for what it is: a complete fraud. And they should do it in verbal terms, easily comprehensible to the general public. If RE is a sound theory its defenders should keep quiet about deficit spending, not attack it hysterically; if it is not, they should immediately start supporting deficit spending. End of story.

I’m reminded of a very illustrative interview of Robert Barro, the father of RE, published in the mainstream Parkin economics textbook where he admits he only chose economics after giving a try at Physics at Caltech under Richard Feynman with whom he recognized that “I would never be an outstanding theoretical physicist” (apud Parkin, “Economics” 7th edition, page 548).

Now, at 67, perhaps it’s time to give economist Barro an extra chance at a new career!

Dear JKH (at 2011/03/31 at 6:22)

In terms of the sequence of diagrams – I think Vimothy has adequately explained them for you. They are a teaching device aimed at explaining graphically to undergrad students the mainstream notion of an intertemporal government budget constraint without central bank expanding the base.

Mainstream macroeconomics considers private agents have knowledge of the government’s intentions and anticipate the future rise in taxes – and act accordingly across time. They thus do not consider the debt to be net wealth but a future tax liability.

best wishes

bill

“They thus do not consider the debt to be net wealth but a future tax liability.”

No, I would say that they consider the debt to be offset by the future tax liability, so that they are indifferent between having the debt and the tax liability, and not having either the tax liability or the debt. The sum is always zero.

And the point that I was making is that if you have an economy in which (nominal) incomes are volatile — whether growing or not — that consists of overlapping generations, then even with perfect credit markets, they will not be able to smooth their incomes unless they have a mechanism for imposing debts on future generations. If there is a 20% chance that nominal income will be lower, then you want to pay less debt service in that period, and more debt service in the good period. But you don’t know what the next period will be, and you need to commit to debt repayment ex-ante. So you wont end up smoothing your income.

In that case, you need government, with an infinite life, to be able to borrow on your behalf. Some generations will get, ex-post, 3 bad periods, and others will get only 1, purely by chance. In order to achieve income smoothing, this means some generations pay more in taxes than others. The stock of government debt is varying across time, increasing during the bad periods and decreasing during the good periods.

Such a system makes all generations better off, in terms of expected utility.

Bill,

thanks

“They thus do not consider the debt to be net wealth but a future tax liability.”

That to me is a very unambiguous statement in terms of Ricardian adjusted government balance sheet economics.

What that says to me is that the Ricardian assumption is that the present value of the debt is offset by the present value of future taxes.

From a Ricardian adjusted balance sheet perspective, that means that the balance sheet of the state nets to a present value of zero, rather than the nominal appearance of negative equity that I personally tend to refer to quite frequently.

And what that adjusted balance sheet also implies is that future taxes assumed in the Ricardian calculus will be sufficient to pay off the debt.

And all of that seems very straightforward to me and I hope it is that simple.

So, sorry, but I still don’t understand the objection to my original supposition.

Most people struggle to fill in their tax statements every year. The notion that they could perform the calculations assumed in Barros model is a complete laugh.

Why even waste time arguing about it ?

Jose,

What MMT tells you is that the Government can set whatever interest rate it desires for term bonds. If continued bond issuance is desirable, the Government can decide the interest rate and meet whatever demand there is for risk free debt at that specified rate. If nobody wants to buy bonds at say 1% it would mean they have better risk/reward alternatives available to them.

In this manner the long pepuated myth that Government are beholden to bond markets is dispelled and the political hot potato of pension funds returns is cooled somewhat.

There would still be unbelievably strong resistance to this proposal. Banks make so much money from the interest rate volatility that the $-4-$ constraint puts on bond issuance.

What (I think) Neil inferred is that a Government could offer it’s citizens the opportunity to transfer their private pension funds into a State superanuation account. The Government could set interest rates at a level that is politically acceptable within the boundaries of it’s overall fiscal policy. In this scenario the Government needs only to plan and budget appropriately for withdrawls from those of pensionable age (which should be easily predictable).

Excellent article in 4 April 2011 The Nation “Beyond Austerity” and only wish it would penetrate the thinking in Washington D.C. at the present! Thanks!

JKH, If I’m following you, what you’re describing is known as the no-Ponzi-game condition. I’ve probably drunk too much Rioja to describe this in an understandable fashion, but I’ve drunk enough to not worry about it, so here goes.

We can use the household and government intertemporal budget constraints (defined as integrals in a continuous time model) to describe the limiting behaviour of the economy. The govt’s constraint is such that the limit of the present value of its debt cannot be positive. Simultaneously, in the limit, the present value of household asset holding cannot be negative.

[NB: Again, this is a feature of the intertemporal constraints and not RE per se, which is and should be conceptually distinct. RE is the optimising behaviour of the private sector in response to changes in the relative mix of borrowing and taxes for a given path of government spending over the economy’s life-cycle. Only government spending affects the economy under Ricardian Equivalence. The amount of borrowing the government does in order to finance this spending is completely irrelevant-it doesn’t affect private consumption and it doesn’t affect private investment. Those crazy neoliberals, eh!]

The no-Ponzi-game condition rules out a situation in which someone issues debt and rolls it over forever, because this would allow the person issuing the debt to have a lifetime consumption that exceeds the present value of their income/resources. Think of the difference between the present value of private sector income and the present value of private spending. If this difference does not approach zero, the govt can run a Ponzi scheme by issuing debt and rolling it over forever. You can get this result in some cases, e.g.my textbook has an example using the Diamond model with a dynamically inefficient equilibrium.

“The no-Ponzi-game condition rules out a situation in which someone issues debt and rolls it over forever, because this would allow the person issuing the debt to have a lifetime consumption that exceeds the present value of their income/resources. ”

This is the crux of the matter. NPV of government income is infinite. This is true of national income as a whole. That is why at the sectoral level, you see everyone servicing debt and never repaying it. Not just government, but the household “sector” does not repay debt, either. Firms do not repay debt. Everyone just keeps rolling debt over forever.

Really this would take only a few minutes to check from looking at aggregate data.

This is one problem with assuming the economy consists of a single infinitely lived agent, and this percolates down the transversality conditions as well. If you want a representative agent, then he will be a different beast than an actual household. For one reason, what would this agent be saving *for*? His retirement?

In an OLG model with infinitely many agents, even if every individual’s PDV of after tax income equals PDV of spending, the PDV of the sector’s aggregate income may not equal the PDV of its aggregate expenditure, so govt can run a Ponzi scheme, but only if it has a dynamically inefficient equilibrium where the real interest rate is less than the growth rate of the economy (govt can issue debt and roll it over and the ratio of debt to GDP will be continuously falling).

Key term being “real interest rate”.

Wayne Swan (Australian Treasurer) would probably not know the difference between real and nominal.

@ Dan et al

Regarding the full employment in sector B, unemployment in sector A scenario, would this not be an instance where tax policy would be used to modify private spending power? That is to say, we’d tax the overheating sector B while providing targeted fiscal support to sector A.

I ask because all the discussion I’ve seen so far focuses on the spending side of the equation.

RSJ “The no-Ponzi-game condition rules out a situation in which someone issues debt and rolls it over forever, because this would allow the person issuing the debt to have a lifetime consumption that exceeds the present value of their income/resources. ”

-Am I right in understanding that the current global situation is one where the person issuing the debt does actually have a lifetime consumption that exceeds the present value of their income/resources and that those who are most adept at this get served by those who are less adept/empowered in the ponzi arts?

“What (I think) Neil inferred is that a Government could offer it’s citizens the opportunity to transfer their private pension funds into a State superanuation account”

A bit more than that. In the UK we have annuities – where you hand over your pot to an insurance company and they guarantee you an income until you die. They back that with government gilts – often index linked ones.

But it is just a exercise in intermediation to make it look like a private actor is paying the pension. In reality the government pays the pension.

So you just have the government offer annuities. You give the government your pot and it will guarantee you an income for the rest of your days. With no cut for some set of middlemen and no risky assets required.

The largest percentage of the UK ‘national debt’ is gilts backing pensions. So you could collapse that national debt, turn it into straight payments from the government. It also has the advantage of providing a mechanism where a reserve build up under zero bonds is reduced in large amounts. Which would help with the instability stuff.

At the moment the entire pension system appears to be operating as a complex job creation scheme for financial people. If you have a Job Guarantee you don’t need that.

“In an OLG model with infinitely many agents, even if every individual’s PDV of after tax income equals PDV of spending, the PDV of the sector’s aggregate income may not equal the PDV of its aggregate expenditure, so govt can run a Ponzi scheme, but only if it has a dynamically inefficient equilibrium where the real interest rate is less than the growth rate of the economy (govt can issue debt and roll it over and the ratio of debt to GDP will be continuously falling).”

No, Abel & Summers (“Assessing Dynamic Efficiency”) have argued (convincingly, I believe), that you need to measure dynamic inefficiency in terms of return on capital, not short term interest rates.

If long term interest rates = growth rate of GDP, then short term interest rates will be less than the growth rate of GDP, and if government debt is of intermediate maturity, say, 6 years, then the interest service cost will be less than the growth rate of GDP.

Nevertheless the return on capital will be well in excess of the growth rate of GDP and the economy will not be dynamically inefficient.

They provide long term data for the U.S., England, France, Germany, Japan, showing no dynamic inefficiency, yet all of these nations have government debt interest rates less than the growth rate of GDP.

That is yet another problem; there is not just one “interest rate”.

RSJ, Right, Abel and Summers find that modern economies are dynamically efficient (“The criterion, which holds for economies in which technological progress and population growth are stochastic, involves a comparison of the cash flows generated by capital with the level of investment. Its application to the United States economy and the economies of other major OECD nations suggests that they are dynamically efficient”). But they use a different approach to the naive one suggested above, based on the idea that you can’t be overinvesting if you don’t reinvest all your capital income–income not reinvested must be consumed. So you don’t need to use OLG models to capture this.

Vimothy,

Thank you again for your answer and patience. I trust you are now either post-Rioja or into a fresh cycle.

I can see where the government budget constraint/identity spawns a range of analyses showing how various deficit and debt growth rates and ratios etc. may be constrained or not constrained in the context of debt “sustainability”. I’ve looked quite closely at Scott’s paper and the Godley/Lavoie paper. All of those types of analyses show sensitivities of debt “sustainability” to various assumptions about all sorts of growth rates around the important parameters, etc. That includes the “surprising result” of Godley and Lavoie.