I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Interest rates up – but its messy

Today’s blog comes to you from beautiful Boomerang Beach, on the mid-North Coast of NSW and within the Booti Booti National Park. I am experimenting with the concept of a mobile office – well a cabin by the beach. Armed with my USB turbo mobile broadband and my portable computer, some files and books (not to mention a guitar and a couple of surfboards) I decided I can work nearly anywhere these days. Connectivity is no longer a problem. So I decided to head north for a couple of days to see how the concept works. Maybe it will begin a gypsy research life although I know one person who won’t allow that to happen! Anyway, it is a lovely setting and I can walk about 200 metres to the surf through the sand dunes. The perfect antidote to the sort of hysteria I covered in yesterday’s blog. Today I am considering corporate welfare among other topics and you definitely need a peaceful and soothing location to delve into that topic in any depth.

Today’s blog comes to you from beautiful Boomerang Beach, on the mid-North Coast of NSW and within the Booti Booti National Park. I am experimenting with the concept of a mobile office – well a cabin by the beach. Armed with my USB turbo mobile broadband and my portable computer, some files and books (not to mention a guitar and a couple of surfboards) I decided I can work nearly anywhere these days. Connectivity is no longer a problem. So I decided to head north for a couple of days to see how the concept works. Maybe it will begin a gypsy research life although I know one person who won’t allow that to happen! Anyway, it is a lovely setting and I can walk about 200 metres to the surf through the sand dunes. The perfect antidote to the sort of hysteria I covered in yesterday’s blog. Today I am considering corporate welfare among other topics and you definitely need a peaceful and soothing location to delve into that topic in any depth.

The local banks have been screaming lately about the proposed BIS liquidity reforms (see the blog – Bond markets require larger budget deficits – for more discussion on the reforms). They have claimed that the new proposals will raise costs (because they will have to hold some of their assets as government bonds) but, of-course, didn’t hesitate to use other government interventions.

While the Australian banks claim they were a step above the rest during the crisis – a lot of self-congratulation went on – the reality is that the Government’s wholesale funding guarantee rescued them from possible funding shortages and insolvency. In the days before the guarantee was announced there was a real fear that the Australian banks would not be able to refund maturing positions, given the severity of the credit squeeze elsewhere. The announcement of the government guarantee changed all of that immediately.

Anyway, the guarantee is about to be withdrawn but the other subsidy to the banks was just increased today.

The RBA today pushed interest rates up a further 1/4 per cent to 4 percent. Here is the statement from the RBA Governor. The RBA seems to be ignoring the fairly gloomy economic data that is coming out of Europe and the US at present and is instead pinning its hopes on Asian growth and focusing on positive trends here.

They claimed today that:

In Australia, economic conditions in 2009 were stronger than expected, after a mild downturn a year ago. The rate of unemployment appears to have peaked at a much lower level than earlier expected. Labour market data and a range of business surveys suggest growth in the economy may have already been at or close to trend for a few months.

The Australian National Accounts data comes out tomorrow so we will see whether that statement is correct. I doubt that we are near trend GDP growth at present. It would have to have been a spectacular reversal of private spending for that to be the case.

The RBA also acknowledge that “(i)nflation is expected to be consistent with the target in 2010” which should shut a few of the hyperinflationists up although that lot never bother to check any data other than the size of the budget deficit and they have a very childlike reaction to movements of the same. Sorry kids, that wasn’t fair … you are much more perceptive than that lot!

The RBA also said that it thinks “it is appropriate for interest rates to be closer to average” and “Today’s decision is a further step in that process”. Previously, they have been using the term neutral. It is a little unclear what any of these terms mean. The neutral rate is allegedly between 5 and 6 per cent and the average target rate since August 1990 (when the data goes back to) is 5.95 per cent. So we are some way from that sort of level and I would doubt that we will get back to there anytime soon.

I am always in two minds when it comes to thinking about these decisions. On the one hand, monetary policy is a very ineffective means of managing aggregate demand. It is subject to complex distributional impacts (for example, creditors and those on fixed incomes gain while debtors lose) which no-one is really sure about. It cannot be regionally targetted. It cannot be enriched with offsets to suit equity goals.

So, fiscal policy (when properly designed and implemented) is a much better vehicle for counter-stabilisation. However, the impact of monetary policy also has to be considered in relation to the levels of debt that households are currently holding. Australian households have record levels of debt and in the financial crisis lost a large slab of their nominal wealth. The RBA has always claimed that the debt was manageable because asset values were rising at a faster rate.

I always found the argument to be dubious given that a rising proportion of the “assets” being purchased with the increased debt were subject to significant private volatility (for example, margin loans to buy shares). But even more troublesome was the direct link between the debt-binge and the real estate booms which have pushed “investment” funds into unproductive areas at the expense of other areas of economic activity which would have generated more employment.

Part of the genesis of the financial – then real – crisis has been the skewing of economic activity towards “financialisation” and away from productive enterprise. So I found the RBA’s line unsatisfactory in that respect. Moreover, now that the household sector has responded to that sort of encouragement, the RBA thinks it is reasonable to punish the most marginal of this group with higher interest rates. Some people will default on their housing mortgages as a result of today’s decision.

Anyway, back to the subsidy theme. Today’s decision also hands over probably millions of dollars to speculators who exploit the so-called carry trade.

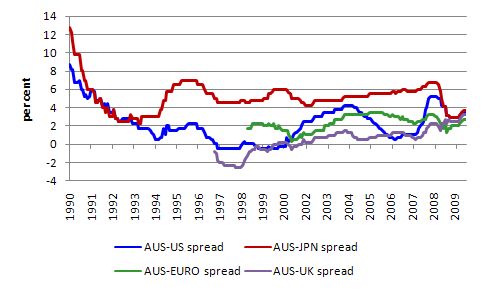

The following graph shows the policy rate spreads for Australia against Japan, the EMU, the US and the UK since 1990. Data is available at the RBA statistics. You can see that in recent years, the spread on all major currencies has increased and is now around 3.9 percent in relation to the US rates and Japan, 3 per cent above the ECB policy rate and 3.5 per cent above the UK rate.

Given these spreads (and the deposits guarantee) the carry trade in the $A has been booming. Anyone with half a wit knows it can borrow at low rates in the US, for example, deposit the funds into our banking system and make a handy deposit.

The gains have been amplified by the appreciation of the AUD which has been mostly driven by the carry trade. So the RBA has not only been seeking to damage aggregate spending in Australia – which presumably is associated with a rising material standards for us – but it has also been giving foreign investment bankers the carry trade subsidy.

Furthermore, the local banks then screw the householders even further into debt.

And if that isn’t enough … the exchange rate appreciation driven by the cross-border fund flows are squeezing the competitiveness of our traded-goods sector particularly manufacturing, which is now in absolute decline (although there was some good news yesterday on that front).

Once again we see the unintended consequences of relying on monetary policy to fight inflation. It can only do that, ultimately, if it scorches the production-side of the economy yet along the way there are other consequences – none of them good.

While on the topic of banks and their activities I note that Paul Krugman is now pessimistic about securing any banking reform at all. In his latest Op-Ed (February 28, 2010 ) – Financial Reform Endgame he says:

So here’s the situation. We’ve been through the second-worst financial crisis in the history of the world, and we’ve barely begun to recover: 29 million Americans either can’t find jobs or can’t find full-time work. Yet all momentum for serious banking reform has been lost. The question now seems to be whether we’ll get a watered-down bill or no bill at all. And I hate to say this, but the second option is starting to look preferable.

He blames the US legislative process which the crisis has exposed to be rather odd to say the least – that is, how can anything sensible actually ever get through the Republicans, the conservative Democrats, and the Administration which is full of deficit terrorists? And this is a nation that has serious weapons!

But this brings the argument in the recently published 2009 Annual Report of the Australian Financial Markets Association into somewhat different light.

The Report noted that the 2008-09 financial year was a “tumultuous one for over-the-counter (OTC) markets, as it was for other financial markets” and required “unprecedented actions were taken by governments, regulators and central banks in an effort to prevent a collapse of financial systems”.

They then said that the:

Basel prudential framework emphasised capital adequacy, capital regulation was imposed in a way that allowed significant build up of leverage and exacerbated the cyclical nature of financial markets. As well, many extremely large, and therefore systemically critical, financial institutions were outside the scope of prudential regulation.

In other words, it failed to do what it had claimed it was designed to do. That is why the liquidity proposals we examined in this blog – Bond markets require larger budget deficits – a now being entertained which is a complete about turn on the capital adequacy paradigm that was touted as being the best way to prevent financial collapse. The BIS and prudential regulators around the world are now talking about regulating the asset side of the balance sheet again to ensure there are enough high quality liquid assets available to cover potential bank runs. This is the old way of regulation.

However, the other problem with the regulative structure has been the way in which a significant amount of “banking” has been able to evade its reach. That is what the OTC markets are all about. OTC markets do not appear on the balance sheets of the banks and there are scant reporting available on these activities which is where the derivatives and swaps and all the rest of it are bought and sold.

The warning signs that the financial crisis was emerging evaded regulators because they had no way of understanding the OTC trade, which dominates the so-called exchange-traded markets (where regulators can see into).

So by failing to deal with this high risk area our legislators are leaving our economies exposed to another collapse.

The Australian Financial Markets Association Report recognises the need for reforms:

As a result, the international regulatory environment for OTC markets is evolving very rapidly, driven by powerful political forces in the US and Europe. Initiatives there have strong influences on regulatory policy in Australia. Legislation put to the US Congress in the middle of 2009 would require all ‘standardised’ OTC derivatives to be cleared through regulated central counterparties (CCPs). CCPs will impose robust initial and variance margin requirements, along with other risk controls, with the effect that customised OTC derivatives will be discouraged. The legislation will also mandate the development of a system for the timely reporting of trades and prompt dissemination of specified trade information. The US reform proposals are internationally significant because they are shaping the practices and infrastructure of global trading in the OTC market.

But that statement is now unlikely to reflect what emerges from the spineless legislatures in the US and elsewhere.

From a modern monetary theory (MMT) perspective there is no need for any OTC markets and they should be outlawed. Banks are public-private partnerships and should only operate to advance public interest. Please read my blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks – for more discussion on how financial markets should be regulated and banks structured.

Somewhat of a digression – cricket

It was announced today that the former prime minister John How had been “nominated as Australasia’s candidate to serve as International Cricket Council (ICC) president from 2012”.

Howard was one the worst prime ministers in our history. Even his own party called him the “lying rodent”. He was divisive across gender, ethnic and socio-economic lines. He promoted racism (very subtely) which is still reverberating now in the form of violence towards Indians and other ethnic groups in this country. He treated the unemployed and other income support recipients with callous disregard.

He ran budget surpluses while our public infrastructure degraded and even at the top of the last growth cycle (which coincided largely with his demise) the total labour underutilisation rate was 9.5 per cent. He significantly cut spending on public education and universities, and, instead, transferred billions of public spending to private elite education and fringe (mad) religious schools.

He lied to the Australian population about WMD and took us into wars that the vast majority did not want to be any part of. He was the self-styled “deputy for George W. Bush”.

He also is only the second prime minister to not only lose government but also his own lower house seat – that is how much he was loathed at the end.

And now, he is about to take over as the boss of our national game.

Here is a video of his cricketing CV. For US and other non-cricketing readers, the bowler (that is Howard in the video) is meant to bowl the ball somewhat further down the pitch (the thing they bowl on) than at his ankles! This video was shot in Pakistan a few years ago while he was visiting the troops he sent on false pretences.

Anyway, cricket is in a mess at present with the capitalists taking it over and turning the game into a circus. What was once a complex web of intrigue traditionally fought out over five 6-hour days with sometimes a result evading th egrasp of both teams is now a bash-fest with US-style blaring music, ridiculous gee-up announcers and diminishing technique.

I guess Howard is well-qualified to wreck it even further.

Total digression: a mystery now solved …

I now know why I ran out of time the other day – it was shorter!

The outlook …

So now I am going back down the beach for a (very) late afternoon surf to follow up from lunchtime. Here is the local beach.

Tomorrow the Australian National Accounts comes out and I will probably comment depending on what the surf is like (-: This mobile office thing could catch on.

That is enough for today.

Hi Bill,

“Anyway, cricket is in a mess at present with the capitalists taking it over and turning the game into a circus.,.. ”

Cricket is helping a lot of people in developing country, especially in the sub-continent, to learn English and compete with the developed world. Initially, it was run by different set of capitalist who changed the rules of the game as they felt convenient. And yes, now the capitalist have changed and they are dictating the future of cricket by promoting the more profitable 20-20 at the expense of test cricket.

As far as John Howard is concerned, he has been chosen as an administrator not as a cricketer. He may not be the most popular cricketer among the Australian left, but he for sure ruled Australia for 12 years, thereby presiding over some of its best economic times in its history.

Cheers,

Sriram

PS: Personally I enjoy test cricket compared to 50-50 or 20-20.

Hi Bill,

As someone who has only recently discovered your blog let me say that your work has been most illuminating. I have a couple of questions that I hope you will be able to help me with. One relates to something you say in this particular blog entry and the other is more general and relates to my understanding of MMT. I will post them here rather than cluttering up your e-mail box as it is quite possible that some of the veterans of this blog will be able to assist me too. It might be helpful to know that I do not come from any background in economics at all but rather academic philosophy.

1. You say here that “even more troublesome was the direct link between the debt-binge and the real estate booms which have pushed “investment” funds into unproductive areas at the expense of other areas of economic activity”. I was wondering if you would be able to expand a little on what you meant there or perhaps direct me to another blog entry which might discuss it in detail. I have to confess that I am a… Brit (a pom!). As I am sure you know, house prices have soared in the United Kingdom over the last 25 years (plus there is a severe shortage of social housing) and “house prices” have become ingrained in the national psyche as an economic bellweather (rising = good, falling = bad) so that comment really caught my eye. Personally whenever I hear that house prices have gone up I groan, since I already cannot afford to buy one but I was interested in a deeper understanding of what you meant.

2. As I have sought to understand MMT I have found it difficult to reorient myself away from the notion that government crediting of private ledgers (sorry if I have misremembered the terminology) corresponds to an inflationary policy of “printing money”. I was discussing fiat currencies and the idea that sovereign governments are different to households with someone yesterday and they maintained that the only way the two were different was that governments could “print money” and this caused inflation. When confronted with this I realised that I didn’t really understand that aspect of MMT so I was hoping that someone could elucidate further or direct me to a blog entry which goes into this specific point. As I suspect with many new to MMT I think I still have deeply ingrained ideas about the supply of money which conjure images of hyperinflation, Weimar Germany and barrows full of notes.

On the cricketing issue, I have to say that test cricket is the shining jewel of the game. Outside of test cricket, the shorter, faster and less subtle the game becomes the less I enjoy it. I know a lot of my friends love 20-20 but I cannot stand it myself.

Best Regards

Nice. Now, if I can just blow up your picture of that beautiful beach then I can have something to dream about as I freeze my butt off in the frozen tundra of midwest U.S.

As for financial regulatory reform in U.S., wishful thinking on our part that this Administration, with Summers and Geithner on board, would dare to actually fight for strong regulatory reform. It made for good news clips to see the Administration propose something but when the sausage making started they let the ‘New Democrats’ of Wall Street take the lead. Now, the strongest piece of the reform proposal – the Consumer Financial Protection Agency is even being weakened beyond usefulness.

Oh, how I wish some times I was on an island kicking back and sipping fruity drinks.

Dear Bill,

This is off topic, but in case you are short of things to write about and/or short of rude things to say about Mankiw, can you do a post on Mankiw’s daft idea that inflation should be boosted so as to reduce real interest rates?

Regards, Ralph.

Hi frolix

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2009/12/27/interview-on-engineer-net/

Here is something on those lines for point 1.

MF-STYLE AUSTERITY MEASURES COME TO AMERICA:

WHAT “FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY” MEANS TO YOU

Ellen Brown, March 1st, 2010

http://www.webofdebt.com/articles/fiscal_responsibility.php

In addition to mandatory private health insurance premiums, we may soon be hit with a “mandatory savings” tax and other belt-tightening measures urged by the President’s new budget task force. These radical austerity measures are not only unnecessary but will actually make matters worse. The push for “fiscal responsibility” is based on bad economics.

When billionaires pledge a billion dollars to educate people to the evils of something, it is always good to peer closely at what they are up to…

We have been deluded into thinking that “fiscal responsibility” (read “austerity”) is something for our benefit, something we actually need in order to save the country from bankruptcy. In the massive campaign to educate us to the perils of the federal debt, we have been repeatedly warned that the debt is disastrously large; that when foreign lenders decide to pull the plug on it, the U.S. will have to declare bankruptcy; and that all this is the fault of the citizenry for borrowing and spending too much. We are admonished to tighten our belts and save more; and since we can’t seem to impose that discipline on ourselves, the government will have to do it for us with a “mandatory savings” plan. The American people, who are already suffering massive unemployment and cutbacks in government services, will have to sacrifice more and pay the piper more, just as in those debt-strapped countries forced into austerity measures by the IMF.

Fortunately for us, however, there is a major difference between our debt and the debts of Greece, Latvia and Iceland. Our debt is owed in our own currency – U.S. dollars. Our government has the power to fix its solvency problems itself, by simply issuing the money it needs to pay off or refinance its debt…What invariably kills any discussion of this sensible solution is another myth long perpetrated by the financial elite — that allowing the government to increase the money supply would lead to hyperinflation. Rather than exercising its sovereign right to create the liquidity the nation needs, the government is told that it must borrow. Borrow from whom? From the bankers, of course. And where do bankers get the money they lend? They create it on their books, just as the government would have done. The difference is that when bankers create it, it comes with a hefty fee attached in the form of interest.

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve has been trying to increase the money supply; and rather than producing hyperinflation, we continue to suffer from deflation. Frantically pushing money at the banks has not gotten money into the real economy. Rather than lending it to businesses and individuals, the larger banks have been speculating with it or buying up smaller banks, land, farms, and productive capacity, while the credit freeze continues on Main Street. Only the government can reverse this vicious syndrome, by spending money directly on projects that will create jobs,..All the fear-mongering about the economy collapsing when the Chinese and other investors stop buying our debt is yet another red herring…A final red herring is the threatened bankruptcy of Social Security…

What is really going on behind the scenes may have been revealed by Prof. Carroll Quigley, Bill Clinton’s mentor at Georgetown University. An insider groomed by the international bankers, Dr. Quigley wrote in Tragedy and Hope in 1966:

“[T]he powers of financial capitalism had another far-reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole. This system was to be controlled in a feudalist fashion by the central banks of the world acting in concert, by secret agreements arrived at in frequent private meetings and conferences.”

If that is indeed the plan, it is virtually complete.

Hi Bill

I must say that I was puzzled by the RBA’s reasons to raise rates: economy and employment at trend, and there could be shock down the track from borrowings costs due to a PIIG default, or China slowing. As you stated the economy does not feel at tend, the DEEWR future employment index is showing that employment is expected to grow at below trend for at least the next 9 months. What would the point be of trying to restrain the economy because there could be an external shock. I would have thought that it was better to be going into such a situation growing rather than slowing. Or is it their new focus on pricking bubbles and therefore, they are trying so slow the residential property market so that people don’t take on debt to buy a house when they think this external shock is coming?

The only other explanation is that just wanted to increase rates based on gut feel, and couldn’t really find a particular reason so have just waffled together various weak arguments, and as they were meeting market expectations, do not expect their reasonings to be dissected too much.

Ellen Brown: Rather than exercising its sovereign right to create the liquidity the nation needs, the government is told that it must borrow. Borrow from whom? From the bankers, of course. And where do bankers get the money they lend? They create it on their books, just as the government would have done. The difference is that when bankers create it, it comes with a hefty fee attached in the form of interest.

The government doesn’t borrow from the bankers, and the Fed turns its profit over to the Fed, not to “the bankers.” The interest on the national debt is paid to the holders of Tsy’s, and banks are not the majority holders of Tsy’s. What is she talking about?

Ralph,

Manikiw appears to have completely lost the plot here.

If inflation rises then I would expect the Central Bank and private banks to react by rasing nominal rates.

The result being that the real rate probably won’t change and if it does it won’t be for long.

I can see where this may be leading though :

“Reducing real wages via inflation as opposed to reducing them by nominal wage cuts.”

Just as ridiculous.

Cheers.

“Banks are public-private partnerships and should only operate to advance public interest.”

This is an interesting idea, which I would probably disagree with for the most part. I don’t think there’s much doubt that there is “some” public element to the banking system – a strong and functioning monetary and banking system is essential for the smooth functioning of a developed economy. This is a good justification for stringent regulation of the banking sector.

But does it really then follow that banks should operate ONLY to advance the public interest?

The problem is that the “public interest” while real, is a nebulous and elusive thing. How would it be possible to determine whether a particular loan was in the public interest? Is granting someone a credit card limit increase in the public interest. Who makes these ultimately subjective decisions?

The unintended consequence of a system like this might be that there is actually less accountability for lending decisions, which could actually be detrimental to the best interests of the public.

An alternative might be to try to isolate those particular parts of the banking system that are most important to the public interest and have those provided by the government as a public service.

An example might be transaction accounts. Why don’t the RBA provide interest-free transaction and savings accounts so every Australian can have access to a truly risk-free way to spend and save money?

In this way, part of the public interest element of banking might be moved back to a public institution. Commercial banks could be left to focus more on profit-seeking activity, and have to fund themselves through equity or deposits from the portion of the public who truly want to take that risk to receive a return.

Dear Gamma

Your ideas have merit and I largely agree with them.

I would however render all financial speculation that cannot be shown to be associated with real economic activity illegal. And I would stop banks acting as commission-seeking agents for such speculation.

best wishes

bill

I have been keeping an eye out for this supposed carry trade, but I don’t see any evidence of it yet.

It is hard for a nation like Australia to be a *target* of a carry trade. It can be a source, if rates were too low here, in which case banks would invest in liquid assets elsewhere, but as a target for foreign investment, the debt market in Australia is tiny and illiquid. Carry trades are high-leverage/high-risk trades, so you want a safe, liquid target investment.

There are only 50 billion in CGS outstanding, and non-financial corporate bond issuance is almost non-existent — I think less than 40 billion in outstanding issues, last time I looked at this. Maybe 150 billion in financial real estate bonds — Bill or others can correct this as I’m going on memory. The primary form of credit in Australia is bank lending, and as result, there is very little productive investment occurring that is not collateralized by land; and this tilts the economy into real estate and resource extraction.

In terms of evidence of a carry trade, it should show up as an increase in foreign liabilities, but these have been steady for a long time, with foreign assets growing more quickly than foreign liabilities, although the level of liabilities still exceeds assets. We will see if the carry trade picks up going forward.

I don’t get all MMT ideas yet, but I want to know this.

From a MMT perspective, can the gov’t deficit spend with currency AND deficit spend with debt at about the same time?

Tom,

I wish you would write her. She is important–has a wide readership. I am sending her your post.

Bill,

Nice spot to contemplate the human economic condition. My hope is that one day we can live in a society that places as much value on ideas and the rigorous examination of those ideas as most western cultures currently place on attaining material wealth ASAP. How can the people of the United States be so short-sighted as to allow GS and the rest to rape and pillage in the name of free markets? It seems like an acute case of Stockholm Syndrome to me. In one of Randy Wray’s postings, he noted that the market was trying to dispatch these characters into the dustbin of history along with Lehman. Until that occurs in one form or another, I think we will be setting sail with an anchor in the sand.

Dear Fed Up

Thanks for your query.

Spending is a flow. Debt is a stock. You do not spend with a stock! So it makes no sense to say you can deficit spend with debt.

A deficit is the accounting outcome of two flows – spending and taxation. A deficit arises when spending is greater than taxation revenue.

Whether public debt stocks change as a result depends on whether the government matches (partially or in full) the net spending that the relative flows determine. When they voluntarily issue debt $-for-$ to match the net spending flow then the change in the stock of debt is just an accounting statement of that action.

I hope that clears that up for you.

best wishes

bill

It does not clear it up for me at all.

I don’t see why the gov’t can’t borrow $100 in savings from a rich person and then spend it.

bill said: “Spending is a flow. Debt is a stock. You do not spend with a stock! So it makes no sense to say you can deficit spend with debt.”

Sorry I’m not getting it. It seems to me that when the gov’t spends, it has to spend with either currency or a treasury check. I consider a treasury check to be a form of debt.

Alan Dunn said: “Ralph,

Manikiw appears to have completely lost the plot here.

If inflation rises then I would expect the Central Bank and private banks to react by rasing nominal rates.

The result being that the real rate probably won’t change and if it does it won’t be for long.

I can see where this may be leading though :

“Reducing real wages via inflation as opposed to reducing them by nominal wage cuts.”

Just as ridiculous.

Cheers.”

I believe it is FAR beyond time for mankiw and his “ilk” to start PERSONALLY suffering a HUGE reduction in real wages and see how he/they like it. Maybe bernanke can then tell him/them they can have “access to credit”? Better yet maybe the spoiled little brats will pick up their toys and leave the country? If so, goodbye and good riddance. Don’t write and don’t come back!!!

Dear Fed Up

I think it is better that you keep them within your own shores. No-one else should have to tolerate them!

best wishes

bill

@pb

Thanks very much for directing me to that link. Much obliged.

Hi, a reader wrote and said something I had written had been questioned on this blog, so I’m jumping in. First though I want to say thanks for some really enlightening articles, Bill! We have a public-banking google group that goes round and round on these issues, and your work has been very insightful and helpful, along with that of Profs Wray and Fullwiler, Marshall Auerback and Steve Keen.

I’m quite concerned about this whole misguided move to “reduce the deficits” by slashing services and selling off public resources. That’s what I was writing about in my article that was questioned by Tom Hickey above, who said:

“Ellen Brown: Rather than exercising its sovereign right to create the liquidity the nation needs, the government is told that it must borrow. Borrow from whom? From the bankers, of course. And where do bankers get the money they lend? They create it on their books, just as the government would have done. The difference is that when bankers create it, it comes with a hefty fee attached in the form of interest.

“Tom Hickey: The government doesn’t borrow from the bankers, and the Fed turns its profit over to the Fed, not to “the bankers.” The interest on the national debt is paid to the holders of Tsy’s, and banks are not the majority holders of Tsy’s. What is she talking about?”

I was a bit lax in my prose, but what I was thinking of was specifically the funding of the deficit, an INCREASE in the debt in the last year of about $1.8 trillion, and that money is coming largely from banks. The Chinese are SELLING U.S. bonds. They are rolling over old bonds but not buying new ones. The excess debt is being soaked up by the Fed, which is trying to stimulate lending by pushing it at the banks, swapping it for the dodgy collateral cluttering up their books. It’s not working — the banks aren’t lending but are using the money to speculate and buy up assets, including buying U.S. securities — but it is the banks that are largely winding up with the bonds. And when the Chinese and Japanese do buy U.S. Treasuries, it’s through their own central banks, which print their local currency and buy dollars with it. When Bernanke had to back off with the quantitative easing last fall because the Chinese were complaining, he resorted to the ruse of buying U.S. agency debt and swapping it with the Treasuries bought by other central banks; but ultimately, it was our Fed buying it, and we the taxpayers were paying interest to the other central banks for the privilege.

Anyway my overall point was that new money is created by banks which charge interest on it, when it could be created by the government interest-free, or borrowed from the government’s own central bank nearly interest-free. What federal securities the Fed does buy are largely handed over to commercial banks and other financial institutions, which do not rebate the interest to the government as the Fed would have done. The ONLY problem with an increasing federal debt is the interest, and that problem could be fixed by simply issuing the debt interest-free, either through the Fed or as interest-free Greenback dollars.

Gamma,

banks de facto are public-private partnerships in the sense that when they fail public steps in and bails them out. It does not matter whether you like it or not but it is the fact of life. To go forward from here public (regulation) should either let them fail at the bank’s own discretion (; or treat them like they should be treated. For instance, have a tax on net interest margin and capital gains that bank makes. 100% of that should to largest possible degree eliminate the public “risk” of someone doing banking. I doubt many banksters will find it attractive then but government could also start negotiating this percentage where the starting position is absolutely clear and each bank has to prove why its risk is lower and public risk is lower and therefore it deserves a lower tax. Until this reality happens all speculation activity should be outlawed.

Dear Ellen,

Welcome to billyblog. I hope you will become a contributor to the debate here. Glad to hear that you are interested in what the MMT’ers are saying. You are an influential voice in accomplishing what Bill has called “the last mile,” that is, getting from operational ideas to both better policy-making for public purpose and fixing a broken system that it undermining public purpose.

Thanks for getting back on this. I had just caught your Max Keiser interview and was quite aware that you know that the Fed profits go to the Treasury, so I was wondering what you meant.

There is a discussion between JKH and RSJ on the composition of Tsy holding at Warren Mosler’s place, at #4 in Response to Dem debate. Right now China is back to being a buyer of US debt, but who buys it is rather immaterial since it is fast becoming the safe haven as Euroland troubles mount. The point is that the US is paying a lot more interest than it needs to, as you observe.

MMT’ers point out that debt issuance is an artifact of convertible fixed rate monetary regime that ended on August 15, 1971, when President Nixon closed the gold window, putting the world on a non-convertible flexible rate regime. Ralph Musgrave has further pointed out here that paying interest carries an opportunity cost in that interest does add to the deficit and increases the deficit/debt without contributing materially to public purpose. So government is increasing nongovernment net financial assets through interest payments without anything to show for it that contributes to the general welfare. This amounts to a give-away of public financial resources to special interests. (Forgive me Ralph if I didn’t express your view adequately.)

MMT’ers point out that debt issuance is a monetary operation rather than a fiscal one affecting the amount of nongovernment net financial assets. Treasury debt issuance just drains excess reserves, enabling the Fed to hit its target rate. The Fed could do essentially the same thing directly by paying a support rate on excess reserves instead. Some MMT’s suggest that the Fed recognize that the natural interest rate is zero, and let the market set rates in light of risk, monetary policy being ineffective.

The proposal to simply issue currency without the façade of debt issuance requires changing the present law in the Us requiring a $4$ deficit offset. This is a voluntary constraint that has no financial necessity in today’s world and is also ineffective at imposing “financial discipline,” as experience shows. Moreover, it stands in the way of elected officials using their power to maintain real output capacity at full employment, along with price stability, by balancing nominal aggregate demand with real output capacity through fiscal policy. This, I think, is doable politically if the people understand how the post-1971 monetary system actually operates.

Formally folding the CB into the Treasury and ending the façade of “Fed independence” is also a priority, I believe. Then, without the political constraints now in place, the US could function operationally with maximum freedom in the engineering sense. Moreover, it would blunt a lot of the conspiracy theory about this. This would be far more difficult to achieve politically, of course, since it would involve repealing or revising the Federal Reserve Act.

Finally, there is the question of the balance between public and private banking. I tend to come down on the side of those who argue that money creation is a public utility and should be a government monopoly, because I do not believe that private banking can be effectively regulated. How this would be accomplished is a thorny question, and specific solutions are beyond my expertise to comment on intelligently. But this is the direction we need to be heading it, I think, unless I can be convinced otherwise. Obviously, there would be fire-storm from the private sector and it is unlikely that this could happen absent Great Depression II, which I don’t think is out of the question, given what is happening.

Best regards,

tom

Gamma, Sergei, in the US banks are also public/private partnerships in that banks are chartered and deposits are guaranteed by the FDIC, hence, closely regulated (in principle if not in practice). The reason for this, beyond protecting the public, is that the financial system is integral to the economy and also national security. There are congressional committees involved, in addition to federal and state agencies, and the Fed Board of Governors is a federal agency.

Fed up,

I suppose it could. In fact, previously, governments did. For example, President Lincoln refused to borrow from the bankers to fund the civil war and issued greenbacks instead.

But now they don’t. Debt issuance just transfers what government disbursed into nongovernment deposit accounts to government securities. It’s a simple transfer of asset type.

Sorry I’m not getting it. It seems to me that when the gov’t spends, it has to spend with either currency or a treasury check. I consider a treasury check to be a form of debt.

Currency (or a Treasury check representing it) is a liability of the government but not a debt in the sense that bank loan that creates bank money (loans create deposits) is a debt. That liability must means that you can satisfy your liabilities to the government – taxes, fines and fees – with a government liability, i.e, the currency the government issues.

Fed Up

I think your difficulty with this lies in insisting that all money is created by debt. This is not the case with the issuance of fiat money. It is better stated that all money is someone’s liability. Thinking of currency in a non-convertible flexible rate system as debt is not accurate operationally. It’s just no the way that the system works under a fiat monetary regime, even when a $4$ deficit offset is required by law, as in the US.

Ellen,

Great to see you here! I was forwarded your recent piece on counterpunch (http://www.counterpunch.org/brown03022010.html), which I recommend to others.

Just one thing that I want to point out, and it’s very minor, but politically important, which is that the interest on the national debt you cite includes interest on debt already held by the federal govt (trust funds, etc.). The correct figure from an economics point of view (neoclassiclal, MMT, or any other) is the interest paid on debt held by the non-govt sector (this is the only debt for which default is even a theoretical possiblity, though ability to pay is unquestioned even for that, of course). This was actually about $187B in the most recent fiscal year, down from about $260B in the previous year.

Best,

Scott

“Some MMT’s suggest that the Fed recognize that the natural interest rate is zero, and let the market set rates in light of risk, monetary policy being ineffective.”

Tom, are you referring to the nominal or real “natural” rate of interest being zero?

nominal

I was referring to Bill’s post, The natural rate of interest is zero!.

So in pursuit of the “natural” policy goal of full employment, fiscal policy will have the side effect of driving short-term interest rates to zero. It is in that sense that modern monetary theorists conclude that a zero rate is natural….

If the central bank wants a positive short-term interest rate for whatever reason (we do advocate against that) – then it has to either offer a return on excess reserves or drain them via bond sales.

Our preferred position is a natural rate of zero and no bond sales. Then allow fiscal policy to make all the adjustments. It is much cleaner that way.

And all those bright sparks in the central bank could be redirected (retrained) to studying cancer cures or engage in something else that is useful.

i’ve read the peice and assumed that you werre referring to that. since he very clearly states that his suggested fiscal policy will create excess reserves that drive the “interest rate” to zero unless drained by bond sales it seems clear to me that he is referring to the nominal interest rate.

Nathan Tankus: i’ve read the peice and assumed that you werre referring to that. since he very clearly states that his suggested fiscal policy will create excess reserves that drive the “interest rate” to zero unless drained by bond sales it seems clear to me that he is referring to the nominal interest rate.

Yes, excess reserves drive the overnight rate to zero. Generally, there will be excess reserves, but one can imagine situations in which that would not be the case, where the government chooses to run a surplus. However, relying on fiscal policy instead of monetary policy to manage the full employment along with price stability would mean running persistent deficits, unless the US trade balance would tip in favor of exports. This is unlikely for a country whose currency is the global reserve currency, meaning that other governments would desire to export to the US to get the dollars they need for foreign reserves. So for all practical purposes the overnight rate would be nominally zero. This is what I understand Bill’s point to be anyway.

omg tom i don’t know how we got into this convo. your name was all over this thread so i thought you were the poster i responded to. it was actually gamma

Thanks Tom and Scott! You all are miles ahead of me in terms of monetary theory, but I\’m pretty good at putting it into housewives\’ prose once I get it myself. Just a writer in search of a good subject, as Mike Whitney says. (Not a housewife anymore but I can still relate.) So I got what you were saying, Tom, down to the two paragraphs beginning \”MMT\’ers point out that debt issuance is a monetary operation rather than a fiscal one affecting the amount of nongovernment net financial assets.\” My eyes glazed over at that point, but I caught the thread again with the last two paragraphs, and I agree that banking should be a government monopoly. I just don\’t write that because it\’s politically unpopular and I figure we have to creep up on these things. I fancy that we can just set up our better model and, in these dire times, the competition will fade away by attrition.

“MMT’ers point out that debt issuance is a monetary operation rather than a fiscal one affecting the amount of nongovernment net financial assets.” i think i may be able to offer a translation to english (something this blog definitely need sometimes): debt issuance has to do with stuff the fed does to control interest rates and other stuff involving the “money supply’ and has nothing to do with the government’s taxing and spending decisions. put another way, the government doesn’t increase the private sector’s net worth when it issues t-bill the way spending money does and it doesn’t decrease the private sector’s net worth the way taxing away money does. i hope that helped ellen. nice to see you on the blog. (other mmters are welcome to give an infinitely better explanation)

bill about mankiw. HA!

That’s probably true.

Tom Hickey, I don’t think my point is getting across. Let me try it this way.

A rich person has saved $100 in currency. An economy needs $105 in spending to prevent price deflation and keep real gdp positive.

The gov’t believes the economy is supply constrained now and in the future.

The gov’t prints $5 in currency, borrows $100 in currency from the rich person, and gives the rich person the gov’t debt of $100.

The gov’t then sends the $105 in currency to a poor person who will spend it all.

Now it seems to me the gov’t has to “earn back” the $100 plus the interest.

If the gov’t tries to print too much currency, the rich person will cash in the bond to drive up prices.

If that does not work, I think I need to put up the wealth/income inequality spreadsheet I sent to bill.

Ellen, thanks for persisting. I’ll try to put it simply, but still make it technically correct. By the way, I am neither an economist or a financial type. I didn’t know anything about this until a couple of months ago when I stumbled upon it serendipitously.

Bank money is different from government money, even though they seem the same since they are both denominated in the currency (dollars in the US). But bank money is created by credit extension (loans created deposits), so everyone’s bank money is someone else’s loan. This means that banks cannot influence net financial assets, since bank money nets to zero.

The government creates government money, i.e., currency, through issuance. The government issues money through its disbursements (“spending”), which end up in deposit accounts. There is no corresponding liability in nongovernment, so these deposits increase nongovernment net financial assets. MMT’ers think of government money in terms of nongovernment net financial assets in order to distinguish it from bank or credit money.

When the government (Treasury) disburses, it creates deposits in commercial accounts, which in turn increase bank reserves with the Fed. Since these are increases in nongovernment net financial assets, the banks in which these deposits occur have excess reserves in the interbank settlement system – in the US, the Federal Reserve System’s regional banks.

This take us to “functional finance.” Fiscal policy consists of government currency issuance through disbursement, which increases nongovernment net finance assets as deposits with corresponding bank reserves in the FRS. These net financial assets are withdrawn by taxation. Here it is important to see that the government does not fund currency issuance in a fiat regime with taxes, nor finance deficits with debt issuance (“borrowing”).

The government issues currency into the economy as net financial assets through disbursements (“spending”). It withdraws, that is, reduces net financial assets of nongovernment through taxation. Thus, fiscal policy regulates the amount of nongovernment net financial assets through “spending” (+) and taxation (-). It’s done by just adding and subtracting numbers in spreadsheets at the Fed. (For all practical purposes, the Treasury and Fed operate in tandem.)

According to MMT, the government must increase net financial assets when the other national sectors – household consumption, business investment, and foreign trade – fall short of generating the level of spending power (nominal aggregate demand) in the economy sufficient to utilize real output capacity at full employment. If the government undershoots, then there is an output gap with rising unemployment. The government must also withdraw sufficient net financial assets through taxation when spending power threatens to exceed real output capacity at full employment, or there will be inflation.

Now we get to debt issuance as a monetary operation, rather than a fiscal one. This is something that I think you may not see clearly yet. Certainly, most people don’t. It’s a bit tricky at get at first because it is a macro phenomenon that pertains to net financial assets.

When the Treasury issues debt (“borrows”), it does not actually borrow anything from anyone at the macro level. The government has already put the net financial assets into the economy that debt issuance just transfers from deposit accounts to Tsy’s at the macro level. It’s an asset switch that alters the composition of nongovernment assets. That’s all. It’s simply a matter of national accounting that describes what happens operationally rather than theoretically.

This transfer of assets from deposit accounts to Tsy’s is reflected at the Fed as the draining of the excess reserves from the interbank market that the currency issuance introduced when disbursements increased deposits. If this were not done, then the excess reserves would be used for overnight lending in the interbank market, and the excess would drive the overnight rate to zero. However, if the Fed targets an overnight rate (Federal Funds Rate or FFR) greater than zero, this complicates matters. So the Tsy’s drain these reserves, allowing the Fed to hit its target rate.

The Fed could accomplish the same thing in other ways, e.g., offering a support rate for excess reserves equal to its target rate. So debt issuance is not only a monetary operation rather than a fiscal one, it is not even necessary at all. The government could just eliminate the interest paid on the debt by not issuing debt, since it doesn’t need to. Government “borrowing” is a red herring.

All the misunderstanding grows out of the false household-government budgetary analogy. This is the basis of the “fiscal responsibility” meme that is so prevalent and used as a scare tactic. It is erroneous because in a fiat system, the government simply issues currency, like a scorekeeper adds points to a scoreboard. No funding or financing is needed.

This means that the federal government in the US as currency issuer is completely different from households, firms and US stats, which are are currency users, hence revenue constrained. The government is not financially constrained, although it is legally constrained at present by the requirement to offset deficits $ for $ with debt issuance. This is a voluntary political constraint, rather than a necessary financial one. This requirement could be removed by Congress at any time. If this were done, then there would be no financial necessity to issue debt at all and it (and the interest) could be dispensed with.

Hope this helps.

Winerspeak also has a short summary here, and Henry C. K. Liu has one here. If you want to see how the national accounting goes, see Bill’s post, Stock-flow consistent macro models.

Fed Up, I don’t think you see yet that at the macro level the currency issuance that corresponds to the debt issuance is already in the economy as an increase in net financial assets that just get transferred into Tsy’s from reserves corresponding to deposit accounts increased by government disbursements. No new issuance required. This is just a switch in numbers in spreadsheets at the Fed. The interest is just another form of currency issuance, i.e., increase in NFA that gets stored in Tsy’s at the macro level, too. You are thinking at the micro level and getting confused. This all reflected in the macro level accounting, irrespective of the various micro flows. As far as the Fed is concerned the micro level is irrelevant. Everything is reflected in reserves and Tsy’s. That’s how the national accounting works.

“Bank money is different from government money, even though they seem the same since they are both denominated in the currency (dollars in the US). But bank money is created by credit extension (loans created deposits), so everyone’s bank money is someone else’s loan. This means that banks cannot influence net financial assets, since bank money nets to zero.”

Tom, this is not correct. There is no financial “thing” which is bank money for one person, and a bank loan for another. Credit extension creates two financial things – (1) the loan and (2) the deposit.

At the moment of creation the loan and deposit are equivalent in value with the borrower and the bank each taking one side of both accounts, but after that point the link between them is forever broken. If the borrower transfers the money to another party (by spending it), the bank has a liability to that 3rd party completely independent of whatever may happen with the loan account.

This is important, because it means that bank money does NOT net to zero – there is always a positive amount of bank money. All bank-created financial instruments may net to zero, but not all bank-created financial instruments are money.

This is not a trivial distinction, because the amount of bank loans and bank money (relative to the size of the economy and relative to each other) and how these change over time can actually have an effect on real economic output.

A particular distribution of financial assets amongst the private sector (eg homeowners generating large amount of debt/financial liabilites offset by real assets in the form of houses) can have large effect on the economy, irrespective of the fact that the non-government sector as a whole (including bank and non-bank) still has not created any net financial assets.

Whether the creation/destruction of net financial assets (through actions of the government and the central bank) is more or less important to the performance of the economy than the creation/destruction of bank money and debt is the question.

I don’t know the answer, but the scale of each is worth considering.

I believe there is something like 180bn of net financial assets in the Australian economy (approx 60bn in the money base, and 120bn goverment debt).

In contrast there is almost 2tn of bank lending and something like 1.2bn of bank created money.

Gamma, I was trying to explain something that is obviously complex in terms of a simple model. Of course, simple models have limitations, since they cannot take everything into account. But in approaching any complex subject, one has to start somewhere. The government money/bank money distinction is designed to explain the meaning of “net financial assets” and why only government can create nongovernment NFA, i.e., because there is no corresponding liability created for nongovernment, whereas bank money creates a nongovernment asset and corresponding liability (“net zero” in accounting-speak).

The distinction between currency issuance and credit extension in money creation is fundamental to MMT, as I understand it, and it underlies the vertical-horizontal relationship of government and nongovernment, which is central to MMT. Through this, MMT brings clarity to macroeconomics that is otherwise rather glaringly absent.

But this brings up a key point about the communication process. Learning takes place through simple conceptual models ideally expressed through metaphors that relate directly to experience. This is the power behind the false household-government budgetary analogy.

MMT is still expressed largely in terms of conceptual models that lack metaphors relating the concepts to experience. Warren Mosler has attempted to provide such a metaphor in his scoreboard-spreadsheet analogy. The simple business card analogy is another. These are good learning tools, but as comments about both of them show, they comes across as simplistic to many people, who offer objections that these simple models are not designed to address.

Hi Gamma,

“All bank-created financial instruments may net to zero, but not all bank-created financial instruments are money.”

Completely agree, and nothing any MMT’er has said should be taken to suggest otherwise. Regardless of how a bank liaiblity/asset combo evolves after it is initially created, the point we emphasize is that this doesn’t change the fact that no net financial assets for the non-govt sector have been created. As I’ve noted many times before, and so has Bill, we don’t like to use the term “bank money,” in part because it leads to the sorts of confusions that you were clearing up. We are very aware of the fact that bank deposits, however created initially, may or may not stay as such, and may or may not even remain on a bank’s balance sheet, and that much the same goes for bank loans or any other asset a bank may create (again, as you’ve explained).

“A particular distribution of financial assets amongst the private sector (eg homeowners generating large amount of debt/financial liabilites offset by real assets in the form of houses) can have large effect on the economy, irrespective of the fact that the non-government sector as a whole (including bank and non-bank) still has not created any net financial assets. ”

Again, agree completely.

Best,

Scott

Hi, thanks. I have to admit to still being a bit mystified, and I’ve spent the last decade trying to grasp all this. I agree we need visual models, something with imagery. A computer game could do it! Here’s the immediate question my public-banking google group keeps going round and round on, if you all would be so good as to offer an opinion. One candidate for governor, Farid Khavari in Florida, has said of his proposed State Bank of Florida:

“We can pay 6% interest on savings. Using the same fractional reserve rules as all banks, we can create $900 of new money through loans for every $100 in deposits. We can loan that $900 in the form of 2% fixed rate 15-year mortgages, for example, and the state can earn $12 every year for every $100 in deposits. That means Floridians can save tens of billions of dollars per year while the state earns billions making it possible for them.”

Some of our members say that won’t work. The bank has to clear the outgoing checks with incoming deposits and won’t have the deposits to cover 9x what it started with. It could borrow from the interbank market, but not for 30 years. What we want to know is, do single banks routinely leverage their deposits into many times their value in loans? Or is that just true for the system as a whole, with each individual bank only lending 90% or less of deposits? (I realize the fractional reserve requirement is obsolete, but I’ve read that banks still lend that way; i.e. Canadian banks hold back about 10% though they have no reserve requirement at all.)

Ellen, the way I understand the Bank of North Dakota, it is organized pretty much like a credit union. I receive 4% on my deposit account with the local credit union, and other credit unions offer 5%, so 6% seems doable. With the state backing the bank there would be little concern about lending for mortgages, and very competitively, too. I don’t know what our credit union offers regarding mortgages offhand, but their credit card rates are much more favorable than the big banks, with much more grace and lower penalty fees.

The State of North Dakota is required to do its banking though the state bank, so it automatically has a huge base to begin with, so if this were the case in Florida, the state bank could be a major player as soon as it launched. However, I don’t think that the financial structure is the fundamental concern. It’s the politics, as always. For example, the Bank of North Dakota is prohibited by statute from offering much in the way of consumer services but basic banking on a limited scale, due to the business lobby. It functions primarily as a banking facility for the state. Florida is a pretty conservative state, so I would expect that getting this done politically the way you would want would be quite a slog, considering the business lobby firestorm against “socialism” that you would face. But it is well worth the fight.

I agree with all that, and in my article on the various candidates proposing a state-owned bank I said they all had different approaches. The question was just whether the bank COULD do it the way Dr. K suggested, or will he get laughed off the stage? Thanks.

Ellen: What we want to know is, do single banks routinely leverage their deposits into many times their value in loans? Or is that just true for the system as a whole, with each individual bank only lending 90% or less of deposits?

The notion that banks leverage deposits, actually reserves, is not the case. Banks lend against capital based on creditworthiness and structure reserves afterward as a liquidity provision.

Banks don’t lend against customer deposits, they lend against bank capital. That is to say, the bank’s customers do not bear the risk when the bank makes a loan. The bank’s equity shoulders the risk and gets the return. Bank capital cushions against loan losses, not customer deposits, which are bank liabilities.

Should a bank fail, then if assets cannot cover liabilities, then deposits, being liabilities of the bank, would be lost along with other liabilities. This is why banks are closely regulated and put into resolution if they immediately (or that the principle, anyway) if standards are not meet. In the US bank deposits are FDIC insured but to a point, but over that point, not.

I don’t think that a state bank would have to concern itself about this issue particularly, since it’s base would be huge if the state did its banking business through the state bank. The customers would be piggybacking this base. For example, the Bank of North Dakota self-insures its deposits and doesn’t use the FDIC guarantee, and with all the state business passing through, there would be no problem with liquidity.

thanks. Yes you’re right, “leveraging deposits” was not the right term. Here’s the issue then: do banks routinely lend many multiples of the deposits that walk in the door? For liquidity purposes, they have to cover their checks at the end of the day, right? And if they lent more than they had on deposit, they would have to borrow from the interbank lending market or issue CDs. So do they do that? Do they borrow a LOT from the interbank lending market and issue LOTS of CDs for lots of loans? Or do they routinely issue less in loans than they’ve got in deposits? Bank balance sheets show loan to deposit ratios of something around 67%. Is that referring to new deposits that walked in the door? Or does it include all those deposits they created as loans? Thanks, Ellen

do banks routinely lend many multiples of the deposits that walk in the door?

no. The banks don’t lend based on the so-called money multiplier. They are constrained by their amount of capital, prudent lending, and the current capital requirement.

For liquidity purposes, they have to cover their checks at the end of the day, right?

yes. This generally takes place in the interbank system (FRS).

And if they lent more than they had on deposit, they would have to borrow from the interbank lending market or issue CDs.

yes. Loans create deposits and those deposits are spent, usually by check. The bank has to have the liquidity (reserves) for settle ment in the interbank system, either with existing reserves or by borrowing reserves in the interbank market. Most deposits created by loans are spent down quickly, since customers borrow for a specific purpose, e.g., a mortgage.

So do they do that? Do they borrow a LOT from the interbank lending market and issue LOTS of CDs for lots of loans?

yes. The interbank market is very active and integral to the system. The financial crisis occurred when the interbank market froze up because banks were unwilling to lend to each other. Therefore, the Fed had to step in as the lender of last resort to unfreeze the system.

Or do they routinely issue less in loans than they’ve got in deposits?

No. Deposits aren’t really relevant to lending because if banks can’t settle checks with their existing reserves at the Fed, they just borrow reserves on the interbank market, and the Fed stand by as the lender of last resort at the discount window, in any case (there are other ways they deal with this, too). Deposits are bank liabilities. They don’t add anything to the bank. They are payables. Loans are assets (receivables). A bank would like to have more assets than liabilities, just like any business. The constraints on lending are bank capital and creditworthy applicants for loans.

Bank balance sheets show loan to deposit ratios of something around 67%. Is that referring to new deposits that walked in the door? Or does it include all those deposits they created as loans?

I don’t know the specifics of the composition, but virtually all of the deposits created by loans are cashed immediately for use, e.g., mortgages, car loans, etc., so the bank arranges for settlement appropriately. People don’t borrow to leave the money in their deposit accounts.

Here are links to a couple of Bill’s post that are relevant. They are also relevant to things you write about.

Money multiplier and other myths

100-percent reserve banking and state banks

Perfect. Thanks Tom!!

Tom Hickey said: “Fed Up, I don’t think you see yet that at the macro level the currency issuance that corresponds to the debt issuance is already in the economy as an increase in net financial assets that just get transferred into Tsy’s from reserves corresponding to deposit accounts increased by government disbursements. No new issuance required.”

Are you seeing the $100 saved is not spent and might cause a drop in real gdp and/or price deflation?

And, “The interest is just another form of currency issuance, i.e., increase in NFA that gets stored in Tsy’s at the macro level, too.”

I don’t know if I will be correct, but I have a sneaking suspicion that currency issuance has not been keeping up with interest payments.

Fed Up, interest payments are a form of government disbursement and so are currency issuance that increase nongovernment NFA. To pay the interest, the government just issues currency to do it, like they do for any other disbursement. They don’t have have to seek approval from Congress as they do with most other disbursements. Congress long ago approved automatic interest payment, so alll the talk about default is just gas, unless Congress would repeal that legislation and refuse to approve currency issuance to pay interest. That will just never, ever happen. It’s totally ridiculous.

A $00 saved and not spent will not cause a real gdp drop or price deflation of itself. This is looking at a macro situation from a micro angle. An individual saver does not affect the system. The system is affected by aggregate behavior in relation to other conditions.

Here is what happens. The Treasury wants to fund something that Congress has appropriated, say, an aircraft carrier. They figure how much they need in their reserve account to cover the disbursements. They they issue debt in the form of Tsy’s to cover it. They exchange this debt issuance with the Fed for reserves. The Fed auctions the Tsy’s into the market and the Treasury cuts the checks to disburse the funds. This is the how debt issuance and currency issuance enters nongovernment.

Primary dealers purchase the Tsy’s from the Fed at auction, and then sell them to nongovernment savers – foreign and domestic (banks, pension funds, etc.) The exact amount that was saved is being put into deposit accounts of the defense contractors by the Treasury in payment for the carrier. The defense contractor then disburses these funds into the economy in payment for resources, subcontractors, salaries and wages, dividends, investment, etc. So the money that was saved in Tsy’s is exactly equaled by the money the Treasury spent into the economy. It’s a wash at the macro level, even though the funds the Treasury spends are not then saved directly by the people receiving them at the micro level.

Ellen,

Just a note to compliment on your comments – excellent questions!

Tom Hickey said: “Here is what happens. The Treasury wants to fund something that Congress has appropriated, say, an aircraft carrier. They figure how much they need in their reserve account to cover the disbursements. They they issue debt in the form of Tsy’s to cover it. They exchange this debt issuance with the Fed for reserves. The Fed auctions the Tsy’s into the market and the Treasury cuts the checks to disburse the funds. This is the how debt issuance and currency issuance enters nongovernment.”

I don’t see any currency issuance there. I believe I see debt being moved around.

Tom Hickey said: “A $00 saved and not spent will not cause a real gdp drop or price deflation of itself. This is looking at a macro situation from a micro angle. An individual saver does not affect the system. The system is affected by aggregate behavior in relation to other conditions.”

How about what will happen if enough rich corporations and rich people save and do not spend?

Tom you says:

“yes. The interbank market is very active and integral to the system. The financial crisis occurred when the interbank market froze up because banks were unwilling to lend to each other. Therefore, the Fed had to step in as the lender of last resort to unfreeze the system.”

but, there are situations wherein the individual bank practically doesn’t pay nothing? I mean, if bank A has a debt with bank B in the interbank market,but bank B has also a debt with bank A, they net zero.

and so you say:

“yes. Loans create deposits and those deposits are spent, usually by check. The bank has to have the liquidity (reserves) for settle ment in the interbank system, either with existing reserves or by borrowing reserves in the interbank market”

If banks borrow reserves in the interbank market, they have to give a security, no? they use also the same security that the individual customer has give to the bank to have a the mortgage loan? because in this situation, theorically the customer “pays” himself the loan. ok, practically no, but the bank doesn’t pay really nothing.

for example, in the ecb regulation, a mortgage loan security is available to have a loan in BC.

what do you think about?